Health in Hawaii: Good News, But Not for Everyone

Overall, the Islands are often ranked as the healthiest state in America.

But diabetes, excessive drinking, vaping and other problems are on the rise and health outcomes are worse than average for some local groups, including Native Hawaiians, other Pacific Islanders, the mentally ill and the poor.

Table of Contents

Part 1: The Challenge

Part 2: We’re No. 1

Part 3A: Diabetes Epidemic Keeps Spreading

Part 3B: How to Beat Diabetes Before it Starts

Part 4: Helping Children with Mental Illness

Part 5: The Micronesian Struggle for Health Care

Part 6: Employee Wellness

Like the other CHANGE Reports, this one on health does not try to be comprehensive. Senior Writer Beverly Creamer writes about major problems and the ways local leaders, government agencies, nonprofits and companies are trying to deal with them. We welcome your feedback and suggestions on this and all the CHANGE Reports on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram using the tag #HawaiiforChange.

The six CHANGE Reports from Hawaii Business Magazine are based on a framework created by the Hawaii Community Foundation. “The CHANGE framework acknowledges the interconnected nature of community issues and zeroes in on six essential areas that constitute the overall well-being of these islands and people,” HCF says.

“By examining critical community indicators by sector, we can identify gaps where help is specifically needed and opportunities where help will do the most good.”

CHANGE stands for:

- Community & Economy

- Health & Wellness

- Arts & Culture

- Natural Environment

- Government & Civic Engagement

- Education

Disclosure: Hawaii Business got support from the aio Foundation, HCF and other organizations, and input from many people, but no one outside the Hawaii Business editorial team had any control over the content of these reports. —Steve Petranik

Part 1: The Challenge

Taking a Good Health Care System and Making it Better

Hawaii is often called one of the healthiest states in the nation and that’s partly the result of Hawaii’s Prepaid Health Care Act.

The 1974 law was the first in the country to mandate all full-time workers be covered by health insurance; the employer must pay at least 50 percent of the premium, with employee contributions not exceeding 1.5 percent of monthly wages. Many businesses also voluntarily cover at least part of the premium for dependents.

Before the law was passed, only 70 percent of local residents had health insurance; afterward, with the help of federal and state government programs for gap groups like the poor and children, coverage peaked at 98 percent.

The percentage of uninsured increased over time but the federal Affordable Care Act, nicknamed Obamacare, reduced the rate again and the latest data show only 3.7 percent of the local residents lack health insurance.

Robert Harrison, chairman and CEO of First Hawaiian Bank and chair of the Hawaii CHANGE Project’s Health Committee, says Hawaii has been fortunate. “We have very high-quality health care, and the cost has been reasonable. Certainly we can always do better on both quality and cost, but overall Hawaii is in a good place now,” Harrison says.

Nonetheless, he says, the state “has the opportunity to take a very good system and make it better. Some of the issues we need to address are how to better care for our homeless population, as well as continuing to deliver quality care at an affordable price.”

Here are some other challenges:

- About 15 percent of Native Hawaiians lack health insurance – three times the average rate of uninsured statewide.

- As many as half of Hawaii’s residents are either at a higher risk of developing diabetes or already have it.

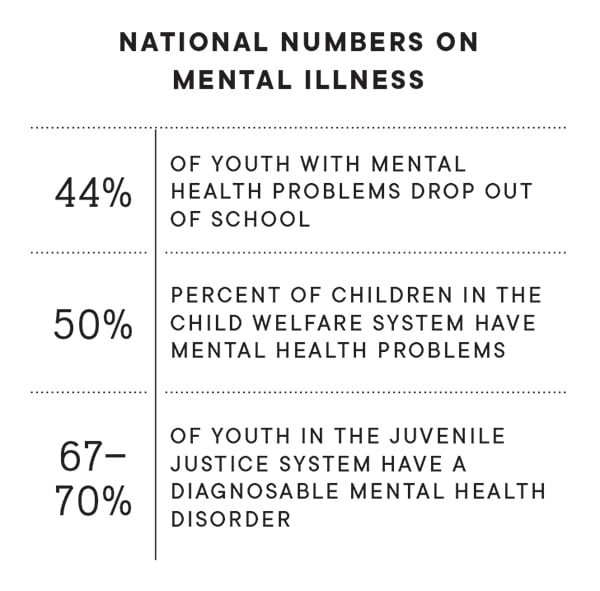

- Youth and children with mental illnesses often fail to get the help they need.

Dr. Virginia Pressler, former state health director, believes the biggest factors harming the health of Hawaii’s people are inadequate access to mental health services, tobacco and vaping, too little physical activity, and fast foods and sugary beverages.

“These lead to substance abuse, kidney failure, dialysis, cancer and heart disease,” Pressler says.

Bruce Anderson, who succeeded Pressler as state health director in May, provides a similar list. “Currently, some of my highest concerns are the increases in e-cigarette use by our youth, climate change and its impacts on public health, and the need for more mental health services in our communities,” Anderson says.

A report last year from the Pew Charitable Trusts provided fodder for critics of the state government. The Pew report ranked states on the percentage of the state revenue that came from federal funds; Hawaii ranked second last among the states, with only 22.7 percent of state revenue coming from the federal government. Much of that revenue funds health programs.

Six states got more than 40 percent of their revenue from the federal government, the Pew report said. Even some states which have relatively high state taxes like Hawaii do much better on that measure: For instance, California and New York each got more than 32 percent of state revenue from the federal government, the Pew report said.

Pressler acknowledges the state government’s problems in that area but says the situation is complex. State programs work hard to apply for those federal funds “only to be frustrated by administrative and legislative policies restricting their expenditure. And then they expire and cannot be used,” she says

Anderson actually disputes the report’s claims. “Over the decades that I have worked in the Department of Health, we have been very aggressive in applying for and receiving federal grant awards to support the health and environmental management programs. During the current fiscal year, the department received $141,369,958 in federal funds, which support health and environmental management programs statewide.”

Another Hawaii health issue centers on Hawaii’s Micronesian community – citizens from the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Most adults in that community don’t have health insurance. U.S. agreements with the Micronesian states once included access to Medicaid or other health care benefits but Congress ended that in 1996. In 2013, the latest year for which data are available, nearly 25 percent of non-Hawaiian Pacific Islanders did not have health insurance.

Harrison says he and a group of state health care leaders that includes Dave Underriner from Kaiser Permanente, Ray Vara from Hawaii Pacific Health, Art Ushijima from The Queen’s Health Systems, and Mike Stollar and Dr. Mark Mugiishi from HMSA, will address key health issues and work with the Legislature and Gov. David Ige’s administration to look for solutions.

Pressler sees the Honolulu rail system as a bright light on the horizon.

“Transit-oriented development allows people to live without cars and consequently walk and bike more, as well as the ability to have easier access to healthy food and employment,” she says.

What Determines How Healthy You Are?

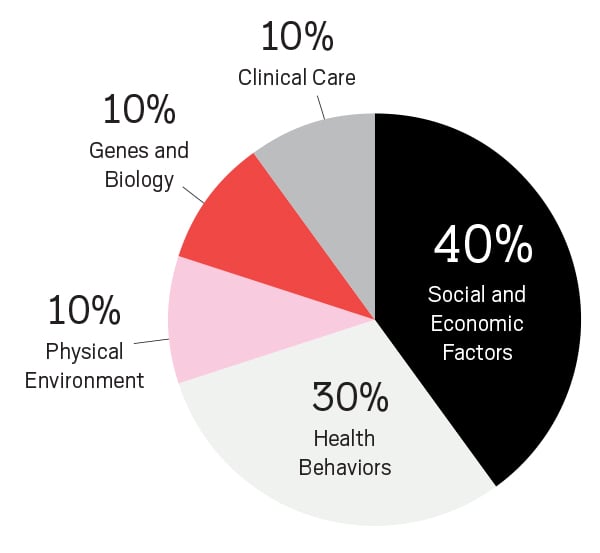

The single largest set of influences on a person’s health are social and economic factors. That means you can tell more about a person’s health by knowing their ZIP code than by knowing their genetics.

An analysis from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found a more than 10-year difference in average life span in Hawaii, based on what ZIP code people live in. The longest average life spans are usually found in high-income ZIP codes and the shortest in low-income ZIP codes.

An analysis from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found a more than 10-year difference in average life span in Hawaii, based on what ZIP code people live in. The longest average life spans are usually found in high-income ZIP codes and the shortest in low-income ZIP codes.

A map showing all Hawaii ZIP codes can be found here.

View the report.

Source: “Public policy frameworks for improving population health,” a 1999 report in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

58% of Hawaii residents who get health insurance coverage through employers. Average annual employee premium after employer contribution: $703.

$2,349 a day: Average cost for an inpatient day in a Hawaii hospital before insurance payment.

Source: eHealth, a national online marketplace for health insurance.

More People Get Food Stamps in Hawaii

Hawaii has increased access to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, SNAP, the program still widely called food stamps, according to the national Food Research and Action Center. SNAP is designed to give low-income people money to buy food.

Hawaii earned a $724,000 performance bonus from the federal Food and Nutrition Service in 2013 because of major improvements in processing food stamp applications faster. In 2011, 61 percent of eligible local households participated, placing Hawaii 49th in the nation for participation. The latest available data shows 84 percent of eligible households participated in 2015, 26th in the nation.

Some Ethnic Groups Live Longer

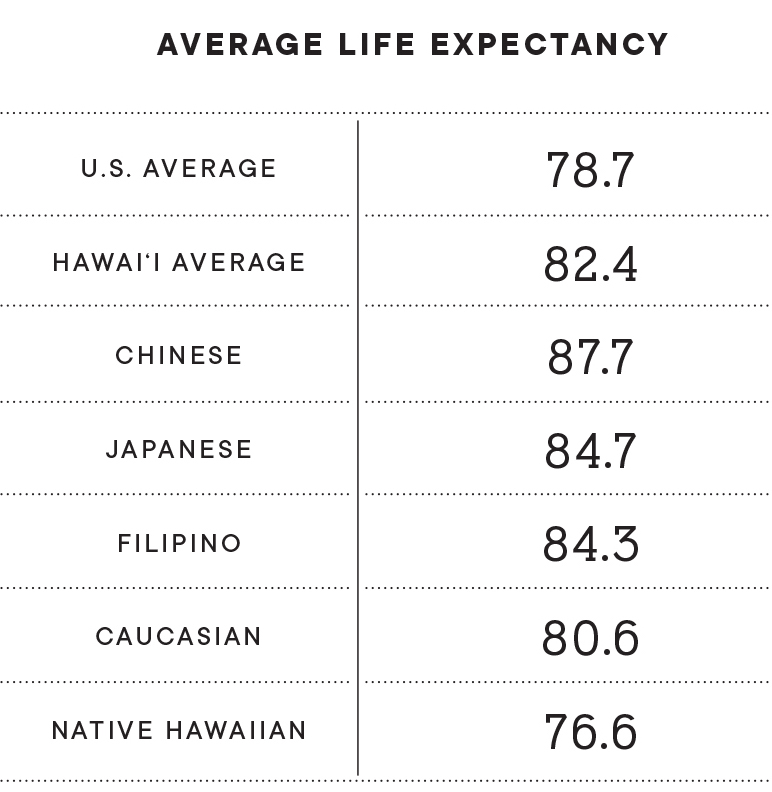

A study of life expectancy among five ethnic groups in Hawaii found that Chinese live the longest on average and Native Hawaiians the shortest. And women in Hawaii, on average, live 6.1 years longer than men.

The 2017 study from a research team at UH also found that in 2010 the average life span for Hawaii residents was 82.4 years, 3.7 years longer than the national average.

This graphic from the study shows the difference in life expectancies among the five major ethnic groups:

━━

Hawaii’s Health Leader

Interview with Bruce Anderson,

director of the state Department of Health since May

Anderson has worked in the Department of Health for more than 20 years, including a previous term as director during Gov. Ben Cayetano’s administration. He has also served as administrator of the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources and CEO of Hawaii Health Systems Corp.

Q: What do you see as the three or four biggest health challenges in Hawaii?

A: Hawaii is ranked as the healthiest state in the nation today. We are fortunate to live in the middle of the Pacific with clean air and water and few industrial sources of pollution. One of the important factors in achieving that No. 1 ranking was the relatively low percentage of smokers here. That ranking is now in jeopardy. The epidemic of e-cigarette use among high school students and young adults will undoubtedly translate to higher smoking rates. And studies have shown that e-cigarette use often leads to smoking tobacco later in life as individuals become addicted to nicotine.

Preparedness and resiliency to hurricanes, flooding and other events associated with climate change is critically important. Hawaii experienced devastating rains and two near misses from hurricanes last year. We can expect these extreme weather events to increase in frequency and magnitude in years to come.

The need for more community-based behavioral health services is obvious to those who recognize the need for a continuum of care for those who live with severe mental illness. One glaring deficiency is the lack of detox facilities where those who have drug- and alcohol-related disorders can recover and receive treatment services. Too many times these individuals end up in emergency rooms or on the streets, repeatedly.

Q: How do we deal with these challenges?

A: Gov. Ige has introduced a bill to ban the sale of flavored tobacco products, which will help discourage their use. The flavors and advertisements are obviously targeted to attract middle and high school students as well as young adults. If it passes, Hawaii would be the first state in the nation to ban flavored tobacco products.

Our executive budget request includes funds and staffing for a new psychiatric facility at the Hawaii State Hospital in Kaneohe to provide secure, state-of-the-art treatment for those with serious mental illness. However, building the infrastructure and making available transitional housing and other community-based support services for those with behavioral health challenges will be an ongoing challenge.

Certainly legislation and policy changes can lead the way to changing our attitudes and actions in dealing with these issues. These are long-term battles that require commitment and a strong mindset toward physical, behavioral and environmental health in creating systemic changes.

These efforts also require strong collaborative partnerships. For example, we are working closely with the Department of Education to reduce e-cigarette use in schools.

Q: Are we winning in any of these challenging areas?

A: We have been making progress in expanding community-based mental health services, and the construction of a new state psychiatric facility at the Hawaii State Hospital in Kaneohe is underway.

We are also making systemic changes. For example, we are developing a comprehensive and seamless case management system for children and adults served by both our behavioral health and developmental disabilities programs. When fully operational, this will result in the delivery of more effective and efficient services for the thousands of individuals we serve daily. Additionally, it will dramatically improve reimbursement for those services.

Q: What about the future?

A: Lack of affordable housing, traffic congestion and the overall cost of living in Hawaii are certainly major challenges we need to overcome. Health must be a primary consideration when planning communities, schools, social services, prisons and other community needs. Bringing healthy lifestyle options to the areas where we live, work, play and worship will improve health outcomes and reduce health care costs. In addition, investing in healthy babies and families will provide the right trajectory toward healthier communities and generations to come.

Fortunately, the opioid crisis is not as widespread in Hawaii as it is in most states. We recently received $8 million in federal funds to deal with the epidemic over the next two years. Nevertheless, more people die of drug overdoses than from traffic accidents and the abuse of alcohol and the use of crystal meth and other drugs continues to be a serious problem.

Childhood obesity, the root cause of diabetes and other serious chronic disease problems later in life, is also a growing problem. We need to help children – and their parents – reduce their intake of sugary beverages, increase physical activity, and make healthy choices in life.

Q: What about health coverage for Micronesians?

A: Historically, Hawaii has been the major provider of health care of Pacific Islanders from the U.S.-associated jurisdictions under the Compact of Free Association, without receiving adequate federal compensation. In fact, tens of millions of dollars of uncompensated care are delivered to those in need every year. We believe that federal Medicaid and Medicare support should be extended to those jurisdictions, just as it is to U.S. citizens living in Hawaii. We don’t turn people away from our emergency rooms who need health care based on their ability to pay. Our hospitals are covering those unreimbursed costs now, which are indirectly passed on to residents and others utilizing our health care system.

Part 2: We’re No. 1

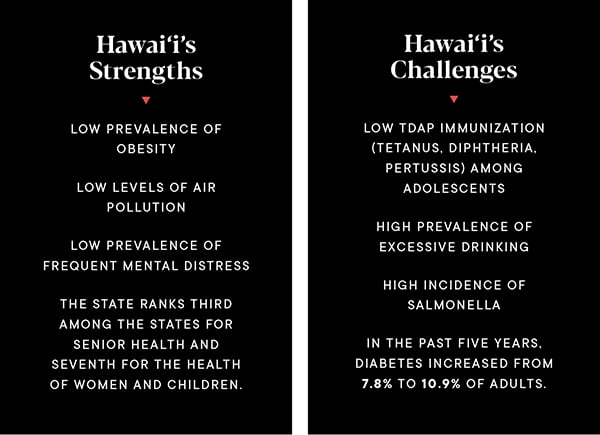

National experts are the ones that often rank Hawaii as the healthiest state overall in America. For instance, Hawaii is ranked No. 1 by the United Health Foundation’s latest annual ranking issued in December 2018. The foundation had also ranked Hawaii No. 1 in five of the past six years.

The Commonwealth Fund also ranked Hawaii No. 1 in its 2018 national Scorecard on State Health System Performance.

The Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index, which Gallup says is based on more than 2.5 million surveys, explores how people experience their daily lives. Hawaii was ranked third among the states in the latest report after placing first the previous year.

Here are some highlights from the United Health Foundation’s 2018 ranking.

Hawaii Among the Top 10 States

Hawaii ranked among the 10 best states in each of these measures (brackets explains the criteria used by the United Health Foundation):

Behaviors:

- Drug deaths (12.3 a year per 100,000 population; nationally 16.9)

- Obesity (23.8% of all adults; nationally 31.3%)

- Physically inactive (23.5% of all adults; nationally 25.6%)

- Smoking (in the past six years, smokers in Hawaii decreased from 16.8% to 12.8% of all adults; nationally 17.1%)

Community and environment:

- Air pollution (micrograms of fine particles per cubic meter)

- Children in poverty (11.5% of all children; however, this measure does not fully account for the high cost of living in Hawaii; nationally 18.4%)

Policy:

- Vaccination of young females against human papillomavirus (62.7% of females aged 13 to 17 years; nationally 53.1%)

- Public health funding ($226 per person; nationally $86)

- Uninsured people (in the past five years, the percentage of uninsured decreased from 7.8% to 3.7% of the local population; nationally 8.7%)

Clinical Care:

- Dentists (75.8 per 100,000 population; nationally 60.9)

- Preventable hospitalizations (23.3 discharges per 1,000 Medicare enrollees; nationally 49.4)

- Primary care physicians (In the past two years, primary care physicians in Hawaii increased from 172.6 to 187.6 per 100,000 population; nationally 156.7. However, local experts believe nonetheless that Hawaii has too few primary care doctors.)

Clinical Care:

- Cancer deaths (161.1 per 100,000; nationally 189.8)

- Cardiovascular deaths (208.1 per 100,000; nationally 256.8)

- Disparity in health status (Difference between the percentage of adults aged 25 and older with at least a high school education compared with those without a high school education who reported their health is very good or excellent. A 13% difference in Hawaii; 29.9% nationally)

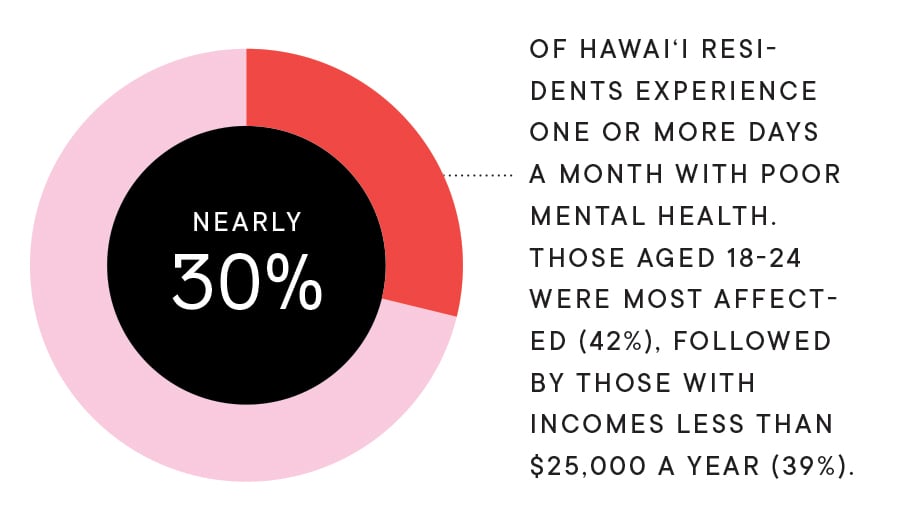

- Frequent mental distress (9.5% of adults; nationally 12.0%)

- Frequent physical distress (10.7% of adults; nationally 12.0%)

- Premature death (6,104 years lost before age 75 per 100,000 population; nationally 7,432)

Lowest Rankings

Hawaii ranked among the 10 worst states in only two categories:

- Excessive drinking (in the past five years, excessive drinking increased from 19.7% of the local adult population to 21.1%: nationally 19.0%)

- Tdap immunization (84.8%% of adolescents aged 13 to 17 years immunized; nationally 88.7%)

Part 3A: Diabetes Epidemic Keeps Spreading

Fighting back against a growing health threat – and one of the most costly

Hawaii’s largest health insurer is launching a major survey of the medical histories of 150,000 of its members in the hopes of pinpointing key health indicators that could lead to developing diabetes later in life.

HMSA’s pilot study aims to identify early on those people who are at-risk for a disease that’s not just a public health crisis, but an economic crisis. Diabetes is one of the most common and expensive diseases to treat.

With that information, says Dr. Mark Mugiishi, executive VP and chief health officer for HMSA, the nonprofit will implement early intervention programs and strategies for at-risk groups, with the hope of preventing the disease.

Mugiishi said HMSA is working with employer groups and their employees to see if the approach works to identify groups in order of most risk to least risk. HMSA covers 750,000 people or about half the state’s population.

“We’re taking a lot of big data and running through it and seeing what kinds of things appear in people’s medical history that allow us to project who in the future would be likely to get it so we can intervene early,” Mugiishi says. “When we identify these different (at-risk) groups, then we’ll work with the employers to offer education, including places to go to work on lifestyle changes.”

While poor diets and too little exercise early in life often plant the first seeds of diabetes, those bad habits can be overcome.

“The most common things you can do is adjust your lifestyle so you move more and eat better – meaning fewer processed sugars and carbohydrates – and monitor your weight by making sure you don’t get too overweight or by staying at an ideal body weight,” Mugiishi says.

“If you do those three things, it’s going to help a lot. As well, it’s been shown with many other diseases that it’s easier to stick with making changes if you do it in a group. That has worked in breaking addictions and in cardiac rehab programs. So if you have a support system around you to encourage you, you will be more successful.”

Diabetes is a severe health problem in Hawaii and getting worse. HMSA went from 30,000 members with diabetes in 2015 to about 50,000 today. Statewide, there are as many as 100,000 people with diabetes, and as many as 25,000 don’t know it.

”It’s so important for people who might be at risk to start incorporating a healthy lifestyle.” – Doreen Nakamura, Director of clinical care, UHA

Wait, it gets scarier: Some medical experts estimate that as much as 30 percent of Hawaii residents have prediabetes, Mugiishi says, based on risk factors and early onset symptoms. You’re at risk if there’s a history of the disease in your family, if you’re overweight, sedentary or just don’t feel good.

“Those are four things that should make you worried,” he says.

Heart disease is a more common affliction in Hawaii, but diabetes comes close, and it strikes Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders and Asians in greater numbers than other groups, although no group is immune. It can lead to strokes, vascular diseases that risk amputation, chronic kidney disease that may require dialysis, and retinal disease that can cause blindness. All require additional care.

All of that pushes up the costs of care – costs that almost always are shared by others within a health insurance network or by government programs.

“The cost of treating diabetes is extremely high,” Mugiishi says. “The average diabetic will spend two times more than the average person (on) health care. In 2012-13 we passed the threshold where more than $1 billion in Hawaii went to treating diabetics. That’s just the total cost of medical care and doesn’t even include the loss of productivity and the cost to society. That’s going to be more hundreds of millions of dollars.”

HMSA and other Hawaii health insurance carriers are constantly reappraising treatment and intervention options, and some of those initiatives are showing promise. In 2015 HMSA hired a large group of care managers and care coordinators to specifically work with patients with severe forms of diabetes.

“They manage the sickest people who have really, really bad disease to make sure they stay on their medications, go to specialists and enroll in community programs that help them manage the disease,” Mugiishi says. That includes up to 4,000 HMSA patients.

UHA, another Hawaii health insurance provider, offers its own staff onsite exercise programs that make it easy for employees to finish work and then work out.

Doris Villorente, UHA’s RN care specialist, does that often. She was diagnosed with diabetes almost 18 years ago but has learned to control it – and now works one-on-one with clients who are referred for case management.

“I didn’t really know what diabetes was about until I became a member of UHA and got involved with various programs here,” Villorente says. “For me it was important to understand what the disease was because you just hear everything and it’s scary. Just understanding how it affects my body was a realization, as well as seeing some of the worst outcomes of other people. That’s what pushed me forward. I want to be well. I became more aware of what I was eating and cut down on the sweets, the white rice, the carbs. I didn’t eliminate them but now I know how to balance them out.”

Vegetables became a key ingredient, says Villorente. “I wasn’t really a fan of salads and vegetables but now I really like squash, broccoli, carrots. My meals used to be grab and go (in her former job) and I think that’s one of the problems – that grab and go mentality. I was just so busy at work that I was eating fast foods maybe three times a week. And when I cooked dinner it was Filipino dishes with high sodium. Diabetes is a metabolic process. It’s not just the breakdown of carbs, but of everything else, including the breakdown of fats. And it’s important to watch your salt.”

UHA tracks its members diagnosed with diabetes and prediabetes. “About 9.4 percent of our membership has diabetes and about 11 percent have been diagnosed with prediabetes,” says Doreen Nakamura, director of clinical care at UHA. “The prediabetes population is a much larger group. But this group still has the opportunity to prevent the disease. That’s why it’s so important for people who might be at risk to start incorporating a healthy lifestyle. That’s why we partnered with the YMCA and their Diabetes Prevention Program. It’s a comprehensive lifestyle program that includes diet, nutrition, mental health, exercise, stress relief, all of which impact the disease.”

”It was the behavior of people decades ago that’s causing diabetes today. Still, you have to start working on it now.” – Dr. Mark Mugiishi, Executive VP and chief health officer, HMSA

It’s also important that once patients are diagnosed with diabetes that they are connected to an endocrinologist or certified diabetes educator who will focus on treatment and lifestyle adjustment that will keep the disease from getting worse, with added complications.

HMSA has additional initiatives, Mugiishi says. One is its latest model for paying health care providers.

“We pay for outcomes now. And one of the big outcome measures is diabetes care. Physicians get paid to monitor and lower hemoglobin A1c levels. That’s a blood test of molecules in your blood that’s a good measure of the risk that someone has for complications of diabetes. If it’s kept low, under 7, the risk of having complications is low. That’s one of the things we pay doctors to manage.”

Payment is also made according to how frequently patients go for eye exams, how often they are checked for kidney disease, and how their weight is being managed.

All of that specific, supervised care is making a difference, says Mugiishi. “We have really good data that the hemoglobin A1c level (overall) is coming down.”

There’s also some good news for those who have already developed diabetes: There are easier ways to monitor blood sugar levels than daily finger-prick tests.

“They have Bluetooth-enabled glucose monitoring,” explains Mugiishi. “It will send your information into a central command center to monitor how you are doing. It’s a personal device that has been around for a while, but the wireless component that sends the information to a central command center where someone is monitoring it is relatively new. A lot of these get the blood composition and glucose off sweat, but there are different degrees of accuracy.”

Mugiishi likens diabetes to climate change. “You kind of reap the harm today that was done 10, 20, 30 years ago,” he said. “It was the behavior of people decades ago that’s causing diabetes today. Still, you have to start working on it now.”

And whose job is it to stem the tide?

“People still feel it’s the doctors’ job, but we’re sophisticated enough today to know that in the provider community it’s everyone’s job,” Mugiishi says.

High Blood Pressure

Almost a third of Hawaii’s population (32%) has high blood pressure – higher than the U.S. rate of 31%. Two local populations have high-blood pressure rates of more than 40%: Japanese and Blacks. Only 60% of Hawaii residents with high blood pressure have it under control.

Source: hawaiihealthmatters.org

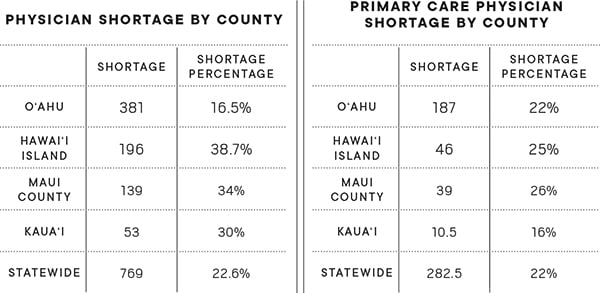

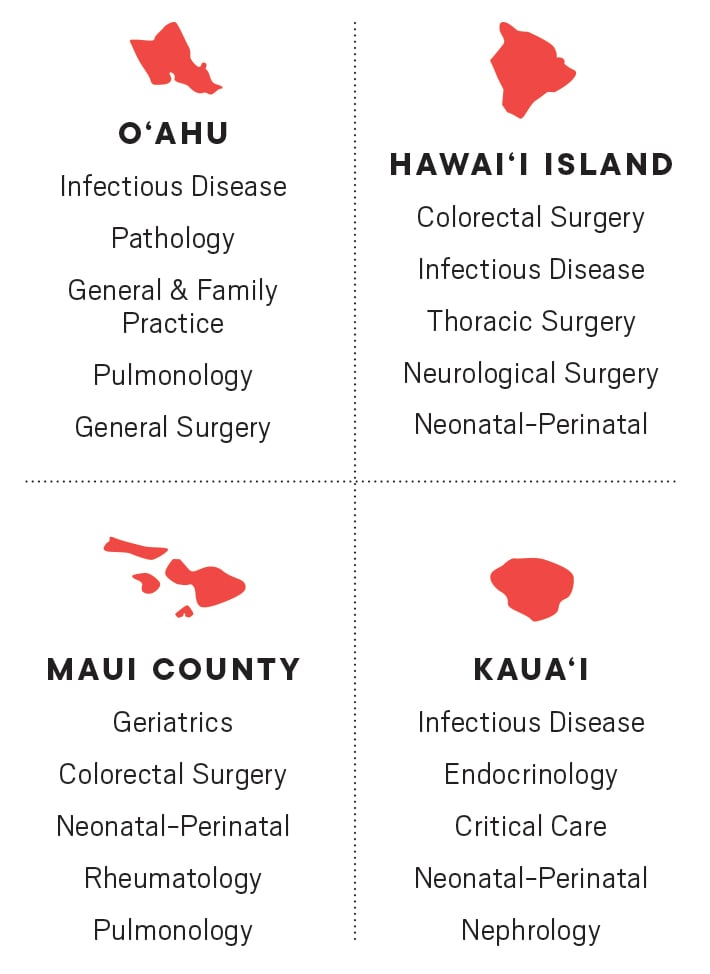

Doctor Shortage in Hawaii (2017)

Biggest Shortages in Specialists

Part 3B: How to beat diabetes before it starts

Marilyn “Mel” Billingsley has been a hiker, backpacker, swimmer and enthusiastic Jazzerciser much of her life. “I’ve always been aware of the importance of being healthy,” says the retired speech and language pathologist.

That’s why it came as a surprise when her doctor said she was prediabetic – a condition suffered by 30 to 50 percent of Americans – and suggested she lose a little weight to stop herself from getting the disease.

“What motivated me the most was being healthy so I could live a long time to enjoy my grandchildren, children and my time with my spouse,” she says.

Through a news bulletin at her church, Billingsley learned about the YMCA’s yearlong Diabetes Prevention Program that helped her change eating habits, lose weight and get support from others going through the same health challenges. She even gave up Spam musubi.

“Our group was incredible. Over time we became close and shared many ideas and spoke openly about our struggles and successes. I stopped eating so much cheese, nuts, fast foods and pizza in order to follow the program,” says Billingsley.

That prediabetic diagnosis and the Y’s program may have saved Billingsley from a potentially debilitating disease, just as it has been saving people at YMCAs all across the nation.

Kristen Chin, health care service clinical coordinator for health insurance company UHA, notes that programs like the one at the Y that are approved by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta are preventing the onset of diabetes.

“Programs approved by the CDC have been shown to reduce the number of new cases of diabetes by 58 percent in adults under 60, and as much as 71 percent in those over the age of 60,” Chin says.

That’s good news for about 110 people who joined the latest classes offered at Hawaii YMCAs. 2019 began with the launch of 11 new groups with 10 participants each. For the first four months there are weekly meetings, which gradually taper down during the year.

Insurance carriers like UHA pay the full price of $690 per person for the program, and other carriers are considering covering it partially or fully once people have a diagnosis of prediabetes.

The program was developed over the past decade and a half, says Christina Simmons, the YMCA of Honolulu’s chronic disease program director.

“The Y has tried to be very community-oriented, and one of the things they look at is what are the big issues of our time in health and wellness. About 10 or 15 years ago we started looking at diabetes rates, which were beginning to skyrocket around the country. We said, ‘Wow, we’ve really got a problem,’ and started doing research, hooking up with the CDC and Indiana University, and started looking at what works to prevent diabetes.”

The first research involved clinical trials with medications, says Simmons. But soon they were evaluating medications vs. lifestyle change, and discovered that “lifestyle change works so much better.”

“At the time it was more of a medical lifestyle change model, but it’s very cost-prohibitive to have a physician do lifestyle change. So we started looking at a medical vs. community model and tra-la, the community model worked much better.”

The Y’s program was born.

Much of the Diabetes Prevention Program’s success comes from the built-in support system that nurtures participants without telling them exactly what to do, says Simmons. “A physician will tell you what to do. At the Y, we don’t tell you what to do. We guide you to the goal, and there are two goals: one is 7 percent body weight loss, and the other is adding 150 minutes of activity to your week.

“In other words, we don’t say you have to do this or that. We work in a group, so it’s a group dynamic. And we use the power of the group to move the group forward. The positive behaviors come from the group and they support each other. That’s very important, because you can really have empathy with other people struggling with the same things you are.”

Simmons emphasizes that people have to be ready for the program. Otherwise, it may not work or they may quit.

But it will work “if you’re ready to really learn and think of the long-term lifestyle change,” she says.

The weekly meetings are a time to talk story, share insights and ideas, and support each other. From those group meetings come partnerships within the group as people exercise together, share healthy eating tips, and otherwise encourage one another.

“We always have a topic,” Simmons says of the group meetings. “For example, one is cues in your environment – either external or internal – that are helping you to exercise, and those stopping you from exercising. What’s your internal justification for eating 12 cookies? We talk about problem-solving skills and we talk a lot about nutrition. A lot of people don’t have a good relationship with food.”

Each group’s coordinator gradually adds new subjects into the meetings, including the expectation that participants will log everything they eat as well as their daily and weekly activities.

“We really pay attention to what you put in your mouth, and your activity log,” says Simmons. “That becomes your frenemy – both a friend and enemy. It’s not about prevention, it’s really about holding yourself accountable to yourself.”

Simmons says the Y is happy to take the program into business offices. “We can do the program outside of the Y. All we need is a meeting room. If there’s a business with 10 or more interested people, we’ll come to you.”

Group facilitator Chris Chow says the gradual and realistic steps of the program help participants understand that they can control whether they develop the disease.

“By empowering participants with personalized tools needed to achieve and maintain a healthy lifestyle, they’re reminded that Type 2 diabetes can be prevented in steps that are not as out of reach as one may think.,” says Chow. “By having participants find something they enjoy doing, their journey toward weight loss and healthy eating is likely translated into long-term healthy habits. It works!”

Billingsley can attest to that. As the program progressed, her physical stamina increased and her attitude toward life improved. “It’s amazing to be able to do things with my very young children, and not be out of breath, walking with an ache in my joints or breathing hard,” she says.

While she knows she may still be at risk for disease because of her family history, Billingsley says: “This has been a life-changing program for me. Every day presents a challenge, but when one has learned the right tools to meet these challenges, you can be successful at anything.”

How to Enroll: Call 548-0951 and ask to speak to the staff in the YMCA chronic disease program

Fighting Back Against Diabetes: The Ekahi Solution

There is no single cause of diabetes, so combating the disease requires multiple strategies, says Dr. Kevin Lum.

Lum is the director of the Ekahi Health Center at Honolulu’s Waterfront Plaza, which offers a comprehensive program to lessen the effects of the disease on the body. Specialists in the year-old program include registered dietitians, a medical social worker, behavioral health specialist, pharmacist and nurse practitioner, as well as an exercise physiologist, stress management specialist and mental health experts.

“We have referrals from primary care physicians, but we also have self-referral,” says Lum, who is also a specialist in emergency medicine. “We participate with all insurances, and while Medicaid is not accredited yet, we expect it to happen.

“The difference with our program is that others may just have six classes and you’re done, but what we want to do is create a partnership with our clients. We want you to come to the program and experience all facets, and we’re there to support you in a long-term way – hopefully reversing it or being successful with management,” Lum says.

“Lifestyle factors are probably the biggest things to address. Eating habits are one of them, but there are also a lot of psychosocial barriers to success. For instance, maybe you live in a house that doesn’t promote healthy eating. As well, stress is also a big contributor to diabetes. Any kind of stressor can increase your cortisone, and when that goes up, it increases your sugar. When you’re in a constant state of stress, you have high cortisol levels running through your body. So we incorporate stress management to learn what is causing those stresses and how to decrease them. Is it your job? Your home life? Do you stress eat? So how can you learn to manage those things?”

Treatment at the Ekahi center begins with a care navigator who looks at the reasons that may keep a person from successfully managing the disease. “The navigator gets to know the person so they can set up appointments with other elements of the program depending on particular needs,” Lum says.

“Hopefully we can knock down their barriers and identify what has been hampering their success in the past.”

As well, says Lum, “we want to encourage them to move to a plant-based diet. We have had so much success at the clinic with the Ornish diet that we want to incorporate it into a wellness diet. Maybe they don’t want to jump into the deep end of the pool at first, but to migrate them over to a plant-based diet.”

The Ekahi clinic also builds resilience in participants with group classes that address diet, stress management and exercise.

“The whole idea around creating these classes is forming a community of people who support one another. Being socially isolated has a negative impact on their health,” says Lum. “This sense of community helps people realize they’re not alone. Becoming friends with others who also want to get better can help people with their own care.”

The facility includes a small gym where participants learn to exercise safely. The exercise program includes aerobic activity along with strength training and weightlifting.

“One of the big issues for people is time management,” Lum says. “People say, ‘I don’t have time to do it.’ We’re always in a rush, so instead of planning my meal I’m going to rush off and make a bad food choice. So our behavioral specialist will work in some of the tools to manage time better. For instance, meal prepping, or planning your day is important. Book 15 minutes to prepare a lunch or on Sunday night make sure you have lunch for the week. Those are the common changes to make but for each person it’s going to be different.”

When participants adopt a plant-based diet, says Lum, they tend to see changes in their blood sugar in the first two to three weeks. “We do see rapid changes. We see people coming off medications as well.”

Lum says Type 2 diabetes is generally considered to be reversible. “And so far we’ve had pretty good success with that. When people are highly motivated, we can see changes within the first month or so. On average, it’s three to four months.”

While the program is typically nine weeks, it can last longer. It can also lead to lifelong friendships among people who now have a common commitment to themselves and their health.

Learn More: For further information about the program or to register, call 777-4001, ext.1

Part 4: Helping Children with Mental Illness

Taking a Good Health Care System and Making it Better

An estimated 2,000 children in Hawaii deal with serious emotional problems. Some are as young as 4.

Mental illness is rarely their only problem. Many are homeless, or have been physically or sexually abused. Often they are poor or come from fractured families or chaotic homes or all of the above. And far too often, there is no adult at home they can talk with.

The state Department of Health’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division tries to care for these children. Their average age has fallen to 13 as they’re being referred at younger and younger ages because the sooner they get help, the more effective the treatment.

“Ten years ago, it was essentially all teenagers,” says the division’s administrator, Dr. M. Stanton Michels. “But if we’re going to impact kids, we need to reach them earlier in their lives, and hopefully we’ll have better outcomes. When a kid is 16, 17, 18 years old, the outcomes aren’t that good. So we need to get into the picture earlier, when kids are more malleable.”

In many cases the children aren’t dealt with at all because they are not diagnosed or a lack of resources.

As they get older, they can end up behind closed doors, in residential programs, in juvenile justice courtrooms, sometimes in locked hospital units.

The picture is especially bleak for Native Hawaiian youth. In 2013, the latest year for which data was available, 32 percent of Native Hawaiian high school students surveyed said they experienced depression; one-fifth said they had suicidal thoughts within the past year.

In addition to the 2,000 young people with severe issues, many of whom get help from the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, another 4,500 receive specialized services from therapists in their schools. And overall, 12,000 Hawaii children and adolescents receive some level of services for non-academic issues through their schools, according to data from the state departments of Health and Education.

In addition to the 2,000 young people with severe issues, many of whom get help from the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, another 4,500 receive specialized services from therapists in their schools. And overall, 12,000 Hawaii children and adolescents receive some level of services for non-academic issues through their schools, according to data from the state departments of Health and Education.

When he took the lead at the state’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division a decade ago, Michels was appalled to discover that one of the children in state care had spent nine months in a hospital setting. He says that no longer happens. The focus has been to reduce the time children spend in institutional therapy in favor of treatment in their homes whenever possible.

“When you have a kid in a certain level of treatment, they can get better, and then they plateau,” says Michels. Keeping them in an institutional setting means just spending money without seeing advances, he says.

“You just don’t keep pouring money at the problem. You have to make sure your money is doing something.”

Reducing long hospital stays saved the division $3 million in Michels’ first year, and improved care for children who were able to return to a normal environment.

When possible, children are increasingly being served in their homes – or in a safe alternative environment – by telemedicine, often using Skype or FaceTime. The technology is especially useful if they live in rural or other difficult to reach areas, helping stretch limited mental health resources a bit further.

“This is the future, not just of mental health, but physical health,” says Michels, “with the current care coordinator going to the home with her laptop. We’re providing the care and we’re keeping the costs way down. The next step is the cellphone.”

Therapeutic care from private institutions is needed to supplement state resources, but residential treatment programs at Castle Medical Center and Leahi Hospital on Oahu have closed in recent years. The Queen’s Medical Center offers acute care for mental illness but no long-term care. Sutter Health Kahi Mohala has stepped into the breach with its 88 licensed beds and a staff of about 200; about half of the patients under its care are young people.

“Six out of 10 Hawaii adolescents who need help aren’t getting it,” says Quin Ogawa, interim CEO at Sutter Health Kahi Mohala. “Mental health issues impact everyone, and our patients come from all income levels. Forty percent are from Neighbor Islands, up from 27 percent in 2017.”

The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division has pushed for two new residential programs for disturbed children: one each on Oahu and Hawaii Island, the state’s poorest county, whose economic struggles were exacerbated last year by Kilauea’s eruption and tropical storms.

The proposed Hawaii Island treatment program would have onsite schooling; the Oahu program would be a 30-day short-term crisis center that could accept eight young people at a time for up to a month of intervention and services.

“These would be young people with substance abuse on top of behavior issues. We need a place to stabilize those kids and provide joint programs,” says Michels of the Oahu program.

“This would give us 30 days to identify a safe environment for the child. The common denominator (among these children) is they need a safe place to be.”

There is a growing recognition of the link between poverty and poor health – particularly long-range physical health and mental health.

“The single largest set of influences on a person’s health are social and economic factors. That means you can tell more about a person’s health by knowing their zip code than by knowing their genetics,” says a CHANGE Report from the Hawaii Community Foundation.

UH Public Health Professor Kathryn Braun, who has studied disease and disability in minority populations for more than 40 years, agrees that geographic zip codes are a closer match to determine health and longevity than cultural or racial backgrounds.

“Health and longevity are inextricably tied to income,” Braun says. “The groups with the highest income in Hawaii are the Japanese and Chinese, followed by the Caucasians. At the lowest end are Filipinos, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

“Disease and longevity patterns follow wealth patterns. The zip codes with the worst outcomes are on Molokai, and what is that but Native Hawaiian and Filipino, very high poverty, low household incomes, and very high Medicaid for the blind and disabled. So you have a population with a lot of poverty, and with that come diseases and disability and lower life expectancy. So it’s not genetic, it’s poverty. And poverty is due in many cases to underlying racism in our system.”

The ALICE Report says that 48 percent of Hawaii’s households are either living in poverty or have working adults yet are barely able to get by. “So we have half of the population that can’t make it. And that spells doom for our healthcare system.,” says Braun. “We are just going to get more and more sick people. People go into healthcare because they don’t have stable housing, or are homeless. Then they can’t manage their disease because they don’t have air-conditioning or electricity.” The more that happens, says Braun, the more those people are going to be going in and out of the healthcare system.

Poverty often leads to depression. In its 2017 report “The State of Mental Health in America,” the nonprofit Mental Health America, formerly the National Mental Health Association, ranks the states according to the prevalence of mental illness among both youth and adults, as well as each individual state’s access to care.

The MHA report, as well as other findings, shows Hawaii lagging far behind other states. Hawaii was:

- 44th among the states with 70.9 percent of youth with depression not receiving treatment.

- 22nd among the states with 4.97 percent of youths reporting a substance or alcohol problem.

- 14th among the states, with 6.4 percent of youths reporting a severe depressive episode.

- 38th in the nation with only 19 percent of youth with severe depression receiving some consistent treatment.

These low percentages demonstrate Hawaii has a way to go to provide needed services, says Leonard Licina, the former long-time CEO of Sutter Health Kahi Mohala.

“Mental illness touches all social classes,” Licina says. “Many of Kahi Mohala’s patients come from good supportive families.” He pointed out that in addition to sexual or physical abuse, trauma, and homelessness, such things as family dysfunction can lead to serious behavioral problems as well as mental illness in the young.

The most recent 2017 Hawaii Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Department of Health in cooperation with the Department of Education, also gives a telling glimpse into the lives of young teens. Data from the report shows that from 2015 to 2017 marijuana use increased almost two percentage points among middle school students, going from 10.2 percent to 11.9 percent. That amounts to 3,300 middle schoolers who have used pot.

The Behavior Risk Survey also shows that use of all illegal drugs among middle schoolers – with drugs offered at school, sold at school or received at school – increased from 8.2 percent in 2013 to 9.1 percent in 2015. Even with that increase, the numbers are lower than they were in 2011 when 9.3 percent of middle school students were able to find drugs at school.

Michels says the way forward is for state departments and agencies to collaborate – both in their work with patients and through changes in funding – to increase their effectiveness for their patients.

With the division’s new call for additional treatment centers, Michels visualizes agencies working far more closely together and pooling resources in some way so that funding is available to respond to whatever the needs may be. This could be through earmarking special funds for these specific purposes, or by other means.

“You will never break down the silos until you break down the funding by pooling agencies, resources and treatment,” he says.

UH’s Braun has spent four decades studying, counseling and developing strategies to fight poor health outcomes. She offers three economic reforms to improve the health of Hawaii’s people.

“No. 1, I would just say raise the minimum wage. Secondly, do something about housing. Increase property taxes so the government has enough money to create low and moderate-income housing that they control, not developers.

“And third, deal with the food system to make food more affordable. Healthy foods are more expensive. If we can do those things, we can see reductions in healthcare costs. And an increase in overall community health.”

Mental Health Issues in Hawaii

32% of Native Hawaiian high school students statewide have experienced depression. One-fifth of all Native Hawaiian students surveyed said they had suicidal thoughts within the past year.

Mental health services are increasingly difficult to access, especially for low-income people with Medicaid coverage. The number of adults served by public outpatient mental health services dropped 36% from 2001 to 2017.

Mental health services are increasingly difficult to access, especially for low-income people with Medicaid coverage. The number of adults served by public outpatient mental health services dropped 36% from 2001 to 2017.

On average in Hawaii, someone commits suicide every two days. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 34.

Efforts Underway:

Prevent Suicide Hawaii Task Force

National Alliance on Mental Illness Hawaii

Hawaii Tobacco Quitline

Hawaii’s keiki

Almost 2,600 children are in Hawaii’s foster care system – the highest number since 2010.

Almost 2,600 children are in Hawaii’s foster care system – the highest number since 2010.- One in 4 children in Hawaii live in households receiving federal assistance.

- Hawaii ranks 49th in the nation for participation in the federal school breakfast program, which provides free and reduced-price breakfasts to low-income students. Only 42% of eligible students participate.

- Most of the 65,000 children who receive free and reduced-price school meals do not get free summer meals. Only 1 out of every 9 children in Hawaii eligible for the federal summer meals program access it.

- Bright Spot: 2016 saw the fewest number of Hawaii’s children living in poverty since the 2008 recession – 31,000 children or 10% of all local children.

Sources: Hawaii Department of Human Services Data Book, Food Research and Action Center, KidsCount.org

Part 5: The Micronesian Struggle for Health Care

There’s profound hopelessness in Hawaii’s Micronesian community, largely around a lack of health care coverage, says Micronesian community activist Jocelyn “Josie” Howard. But there is also hope that the next generation of Micronesians will rise up and take their place as other immigrant groups to Hawaii have done.

The state’s Med-Quest program for low-income people covers Micronesian children 18 and under, elders 65 and above, pregnant women, and those who are blind or have other disabilities. But other Micronesians without U.S. citizenship are not eligible for the state-sponsored health insurance; those who do not get coverage through an employer can buy health insurance but many can’t afford it.

As a result, only 1 in 4 Micronesian households has health insurance, according to data collected by Michael Levin, a consultant with PacificWeb LLC, whose career as a demographer has taken him to the U.S Census Bureau, Harvard University and, most recently, the East-West Center. Levin tracked the Micronesian experience in Hawaii through surveys in 1997, 1999, 2003 and 2012.

Even Howard is fearful, though she has worked in Hawaii for 30 years and has medical coverage through her job.

“If I lose my job I will not qualify for Med-Quest,” says Howard, who is program director for We Are Oceania, an organization assisting Pacific Islanders, including Native Hawaiians. “And the Healthcare.gov option is not affordable for me.”

With the Compact of Free Association created in 1986, the U.S. entered into agreements with three Micronesian states: the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. COFA allowed Micronesians easy immigration to America and included eligibility for Medicaid or low-income health care benefits in the U.S., but 10 years later Congress withdrew the health care benefits.

That placed an enormous burden on the more than 15,000 Micronesians in Hawaii and on the state health care system, as uninsured Micronesians often use hospital emergency rooms for their health care needs.

“Most people when sick go to the ER. They can’t help it,” says Howard. “Some people are accessing urgent care services. And some tried to come to We Are Oceania to apply for any health coverage available to them, but most of the times there was none. We established partnerships with Hoola Health and Urgent Care Clinic, and have been referring people without health coverage there for medical treatment.”

Researchers point out that Hawaii has long been a popular draw for Micronesians because of the quality of the state’s medical care compared to the care offered on their home islands.

“The medical situation in Micronesia is so bad that they are generally glad just to be in a place where they can be reasonably confident that they will get adequate, if not superior, care,” says Levin. He cites the example of a Micronesian woman who gave birth to a healthy daughter 10 years ago while studying at UH Hilo. “When she and her husband moved back to Pohnpei, she had three miscarriages before becoming pregnant again,” he says.

During that latest pregnancy, “She came to Hawaii on the health insurance provided to Micronesians. She had pregnancy related diabetes, which was measured several times a day and precautions taken. And she was on bed rest for the last month of her pregnancy. She had a very healthy daughter who is now 3 years old. Obviously each pregnancy is different, (but) it is unlikely that the result would have been the same in Micronesia.”

Levin notes that many Micronesians come to Hawaii specifically because of medical issues like a need for dialysis or other “machine-related” treatments and diseases. Their move from a traditional diet and lifestyle to Western food and a more sedentary life has led to conditions like hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol.

A Hawaii-based study published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2016 noted that Micronesians were “significantly younger at admission (to hospital) than were comparison racial/ethnic groups” and the severity of cardiac and infectious diseases was also significantly higher than that of all comparison racial/ethnic groups. As well, it was higher than that of Caucasians and Japanese for cancer and endocrine hospitalizations, and higher than that of Native Hawaiians for substance abuse hospitalizations.

Researchers Megan Kiyomi, Inada Hagiwara, Jill Miyamura, Seiji Yamada and Tetine Sentell concluded that “Micronesians were hospitalized significantly younger and often sicker than comparison populations” and that they are a particularly vulnerable group.

The study also pointed out that Micronesians have experienced “a variety of historical events that have contributed to poor health, including U.S. nuclear testing in the region, and the disruption of traditional economics, cultures and diets.”

Lack of health care coverage is just one issue facing the Micronesian community in Hawaii. As Micronesians moved to Hawaii from the mid-1990s and into the early 2000s, they also faced the difficulties of finding housing and jobs with a living wage, and racial prejudice. A disproportionate share of the state’s homeless population is Micronesian.

For Josie Howard, hope lies with the next generation of young Micronesians and their ability to make their voices count at the ballot box.

“Our children are U.S. citizens and they are voting now,” Howard says. “So, just like every immigrant group that came to Hawaii before us, and are policymakers in Hawaii, the sons and daughters of Micronesia who are U.S. citizens have to rise up and follow in their footsteps.

“This is our new home. I would like everyone to work together. Together we make the Hawaii community, and that’s why everyone needs to be included.”

Part 6: Employee Wellness

Promoting employee wellness is now company policy at many local businesses

Tuesday Pires-Piimauna remembers her dread as she faced the stairs to her first NuFitness class. “They did me in. … I could barely walk up the steps,” she says.

But she persisted, signed in at the registration desk and took the first step to a healthier life – thanks to support from her employer, Bowers + Kubota Consulting, where she’s a project manager and associate.

Pires-Piimauna suffers from lupus, a disease that once controlled her life. “I was taking 26 different medications. Medications told me when to get up, when to sleep, when to feel good, when I needed more.”

That was before she participated in her employer’s Whip It (Wellness and Health for the Individual Program) that reimburses up to $300 annually for the cost of exercise classes or equipment. The company says it has spent more than $100,000 on employee reimbursements since the program began and more than 70 percent of its 200 workers participate.

“B+K challenges us to be fit and healthy, and also rewards effort,” says Pires-Piimauna who has turned her health around and come off all of her medications. “Half the battle is showing up. This year I also won a cash prize for my Whip It points.”

Bowers + Kubota Consulting is one of hundreds of Hawaii companies that actively support employee health with wellness programs.

“We offer our wellness programs because we recognize that fostering healthy individuals translates to an improved quality of life, high job satisfaction and healthy work environment,” says Dexter Kubota, the firm’s co-founder and president.

“The program is a multifaceted approach to wellness by offering support in fitness, nutrition, emotional counseling, community outreach and financial guidance, among other things. Wellness has become intrinsic to our company culture. The intent is for this wellness culture to also permeate to the homes of employees, benefiting their families as well.”

All of that leads to stronger communities and potentially a reduction in health care costs that could theoretically reduce health care costs statewide.

Robert Harrison, chairman and CEO of First Hawaiian Bank and chair of the health and wellness committee for the Hawaii Change Project, has high regard for local wellness programs.

“Employees are the most important asset any organization has, and improving their wellness helps all of us. The better our employees feel, the more they are able to enjoy life and contribute to both their family and the community. It helps the community be more positive and productive,” Harrison says.

Dr. Virginia Pressler, former director of the state Department of Health and former executive VP and chief strategic officer with Hawaii Pacific Health, agrees with that evaluation, and sees a definite community benefit from companies committed to their employees’ overall well-being.

“Work site wellness is important as a way to increase awareness among employees on how to care for themselves and their families,” says Pressler. “That also means work site health policies that foster healthy living such as removing doughnuts and sugary drinks from work site meetings, encouraging walking, biking and mass transit to get to work, and encouraging policies like flex time to allow for enough sleep, family time and physical activity.”

Mark Fukunaga, Chairman and CEO of Servco Pacific Inc. and the 2018 Hawaii Business Magazine CEO of the Year, has long championed a wellness strategy for his employees. As part of a wide array of wellness programs and activities, 10 years ago Fukunaga oversaw construction of a gym for his team at the company’s Mapunapuna headquarters. Hundreds of Servco employees have benefited from the classes and sports it offers.

“From a business perspective, the rising cost of health care is a concern that touches our entire economy,” says Fukunaga. “Employers benefit by taking proactive measures to enable employees to be more accountable for their own physical, mental, social and financial wellness. If every employer in some way positively influences the health of that part of the community that works for them, the entire community benefits.

“The effect is a chain reaction. If we can impact our team members, those that participate will impact other team members. It helps create healthier habits, which they then take home and into the communities where they live and play. I think more companies are becoming aware of the value this kind of program can bring, and are implementing solutions in varying degrees.”

Daphne Mendiola, a senior payroll specialist at Servco, joins in exercise classes at the company gym four days a week. Her fellow employees are now also exercise buddies.

The attractive, spacious Servco gym opens at 5 a.m. and accommodates many classes as well as sports like pickup basketball games.

“We work hard but we also have fun,” Mendiola says. “I have a desk job and sit all day, so after attending the exercise classes I feel more energized. I did lose weight and my clothes fit better.”

Each year, as part of the Best Places to Work survey sponsored by Hawaii Business Magazine, leading local companies are honored for supporting healthy workplaces and healthy workers.

Companies’ health and wellness offerings run the gamut. Howard Hughes Corp.’s Hawaii employees are offered surfboards, bicycles and Fitbits. Swinerton Builders offers discounted rates to 24 Hour Fitness and free registration for the Great Aloha Run. Island Insurance brings Weight Watchers programs right into the office. American Savings Bank promotes a wide range of challenges for employees to get healthier.

Even smaller companies, with fewer resources, are finding ways to support the health of their workers. Hawaii Diagnostic Radiology Services employees receive annual reimbursements for the wellness program of their choice. Skyline Eco-Adventures on Maui provides reimbursements for gym memberships. Atlas Insurance Agency features a monthly on-site farmers market that brings fresh items to the office.

Peter Burke, the co-founder and president of the Best Companies Group based in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, which administers the Best Places to Work surveys for Hawaii Business Magazine, says wellness programs help to engage employees. And that, says Burke, whose organization runs similar surveys in 23 other states and four countries, leads to better employee performance and ultimately better bottom lines.

Five years ago, Linda Kalahiki, senior VP and chief marketing officer of UHA Health Insurance, helped launch the Hawaii Health at Work Alliance, which advocates for wellness programs statewide. HHWA now includes more than 200 companies. The alliance shares best practices regarding workplace wellness, and has created a support network for Hawaii companies.

For her part, Pressler welcomes company wellness programs, but says they should only be part of the picture. She’d like to see greater focus on “serious policy changes to allow employees and their families to eat better, stay physically active, avoid tobacco and vaping, and take care of their mental health.

“We need to change the entire culture in the U.S. to focus on health, much as Japan has done as a nation,” says Pressler. “And we need to create a culture of health throughout our state. That means livable, walkable, bikeable communities, and more personal understanding of how to be healthy.”

Learn More

Many efforts are underway to improve health in Hawaii; the Hawaii Community Foundation lists these sources: