Education in Hawaii: Smart Innovations and Persistent Problems

This report on our public schools offers many reasons for optimism and just as many causes for concern about difficulties that have lingered for too long.

Table of Contents

Part 1:

Real-World Learning

Part 2:

Student Success

Part 3a:

Trying to Solve the Teacher Shortage

Part 3b:

New Way to Home Grow Teachers

Part 4:

Designing Schools of the Future

Part 5:

Different Approach

Part 6:

How You Can Help

This report on education does not try to be comprehensive. Staff Writer Noelle Fujii focuses on major issues in public education – the good and the bad – on smart innovations and ways forward, about key challenges and possible solutions. It concludes with a section on how you and your organizations can support our public schools. We welcome your feedback and suggestions on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram using the tag #hawaiiforchange.

The six CHANGE reports from Hawaii Business Magazine are based on a framework created by the Hawaii Community Foundation and adopted by the Hawaii CHANGE Initiative. “The CHANGE framework acknowledges the interconnected nature of community issues and zeroes in on six essential areas that constitute the overall well-being of these islands and people,” HCF says.

CHANGE stands for:

- Community & Economy

- Health & Wellness

- Arts & Culture

- Natural Environment

- Government & Civic Engagement

- Education

Hawaii Business published the first CHANGE Report in the February issue: It covered Community and Economy by focusing on the ALICE families, the 37 percent of local households that have at least one working adult but are barely getting by. Further reports will appear in April, May, June and July. As HCF says, “By examining critical community indicators by sector, we can identify gaps where help is specifically needed and opportunities where help will do the most good.” Find all the reports at hawaiibusiness.com/changehawaii.

Disclosure: Hawaii Business got support from the aio Foundation, HCF and other organizations, and input from many people, but no one outside the Hawaii Business editorial team had any control over the content of these reports.

━━

Part 1: Real-World Learning

An exciting transformation is occurring in Hawaii’s public schools and those changes are supported by a broad consensus, including education leaders inside and outside the DOE, nonprofits, foundations and even Mainland experts. Big challenges remain – such as low test scores, chronic absenteeism and poor teacher retention – but hands-on projects that address modern problems better engage all students while preparing them for a world in which traditional careers are dying or being reinvented.

Public education in Hawaii is undergoing a transformation.

No longer is school just about teaching students how to ace standardized tests required by a top-down mandate. Instead, the focus is increasingly on learning that’s hands-on, relevant and driven by students.

No longer is school just about teaching students how to ace standardized tests required by a top-down mandate. Instead, the focus is increasingly on learning that’s hands-on, relevant and driven by students.

The classroom is no longer confined to four walls; it’s common for students to learn math concepts at a loi, polish their writing on a public service announcement and learn about careers in internships. In these settings, teachers are often alongside them serving as resources, rather than as experts lecturing at the front of a room.

Leaders in education inside and outside the DOE and elsewhere in government are encouraging this transformation and the empowerment of schools to be innovative in how they teach. After all, schools have a bigger challenge than ever: to prepare students for a rapidly changing global economy and jobs that either don’t yet exist or will be constantly reinvented.

Click here to find out how you can help.

Catherine Payne, chair of the state Board of Education, says Hawaii has had this conversation for decades but has finally reached a tipping point. “You have to reach that point where people are all ready to do what needs to be done – and I think we’re there,” she says.

Payne formerly worked as a public school teacher, vice principal and principal and was most recently the chair of the State Public Charter School Commission. “I think there’s recognition that we cannot continue to do things in the same way we’ve been doing them. We cannot keep chasing test scores as the primary reason for our existence.”

Many agree that this is an exciting time for public education. Joshua Reppun, a former teacher, says: “Now they’re hearing this message: school empowerment, school design is yours, teacher collaboration, get students involved in their own education, personalized learning. … This thing that has been predisposed for a very long time, to do innovative, imaginative creative things in education for the benefit of student engagement, is now popping up everywhere.” (Disclosure: Reppun is married to Hawaii Business publisher Cheryl Oncea.)

Change Needed

“Today, I think a lot of us would agree that too many students – especially those furthest from opportunity – are unprepared for the challenges of the 21st century,” says Lisa Mireles, a director of district and school leadership at PBLWorks and a former school renewal specialist for the Kauai Complex Area.

Schoolchildren who focused for generations on how to memorize material and replicate low-level tasks have turned into adults who don’t know how to reinvent themselves as the economy changes and careers either change or disappear, says Ted Dintersmith, a former venture capitalist who visited all 50 states to learn about best practices in education. He produced and funded the documentary, “Mostly Likely to Succeed,” which examines the shortcomings of conventional learning and encourages schools to rethink how they should prepare students for the future.

Schools in their current form were created for an industrial society that produced workers who could be cogs in a machine, says Buffy Cushman-Patz, school leader of the School for Examining Essential Questions of Sustainability, SEEQS, a charter school based at Kaimuki High School.

“We’re training kids that (when) a bell rings, to get to class on time, you sit down, you do what someone says, the bell rings and you do some completely other different subject that’s not related – and you repeat that six times a day,” says Rick Paul, who just retired after serving as Hana High and Elementary School’s principal for 14 years.

It hasn’t helped that, in the last couple of decades, life in schools has revolved around standardized reading and math tests thanks to the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, a federal law that reprimanded schools if they failed to produce higher scores each year, and Race to the Top, a competitive federal grant that Hawaii received to raise test scores, ensure college and career readiness and close achievement gaps. This contributed to a top-down mentality where central administration told schools what do, including what curriculum to use, says Corey Rosenlee, president of the Hawaii State Teachers Association.

These testing mandates forced many schools to focus their teaching on what would be on those tests, he says. And standardized tests don’t teach students much, he adds, except that there’s only one correct answer to a problem – and that’s not what students need to learn today.

Mireles says as Hawaii moves toward a more innovative, knowledge-sharing economy, schools must think of themselves less as dispensers of knowledge and more as facilitators of knowledge creation. They also need to understand that significant learning takes place everywhere – in and out of school.

“Many of the jobs we’re preparing our students for today don’t exist,” says Gov. David Ige. “It’s that whole notion that public schools are being asked to do more, to prepare our children for jobs that don’t exist today.” That means what and how schools teach have to change, he says.

College Graduation – Only 62% of first-time, full-time UH Manoa students will complete a degree or certificate within eight years. The rate for community college students is 26% to 40%, depending on which community college they attend.

Click here to find out how you can help.

Turning the Tide

Conversations surrounding school empowerment have been going on for decades, Payne says, recalling former Superintendent Charles Toguchi’s calls for decentralization when he led the DOE from 1987 to 1994.

Today, most people see school empowerment as necessary, says Randall Roth, a retired UH law professor and former president of the Education Institute of Hawaii, a think tank made up of current and former educators and administrators who have advocated for schools to have more decision-making power since its establishment in 2014.

Desires for school empowerment and innovative educational methods are echoed and supported in three documents:

- Hawaii’s Blueprint for Public Education, a guiding document that was completed in 2017, outlines the community’s vision for public schools;

- The DOE’s 2017-2020 Strategic Plan;

- The state’s plan for how it will use federal funds authorized under the Every Student Succeeds Act, a 2015 law that replaced No Child Left Behind and grants states more flexibility to design their education systems.

Several sources say they’re encouraged that school empowerment is supported by key decision-makers like the governor, DOE superintendent and Board of Education chair.

“When you have the three people in alignment, then school empowerment really breeds innovation,” says Ray L’Heureux, chairman and president of the Education Institute of Hawaii, which is working on a fiscal transparency tool to see what the DOE’s resources are, where they’re going and who’s making the decisions.

School empowerment means putting the decisions that affect students as close to them as possible. Those decisions could include things like instruction, curriculum, support services and facilities, though Ige adds that there are still statewide standards that schools must adhere to.

Christina Kishimoto, who has been superintendent of the DOE since August 2017, says this means celebrating each school’s uniqueness. The department’s main strategies to pursue this approach focus on incorporating student voice, encouraging teacher collaboration and purposefully designing schools in ways so every student is engaged in rigorous and innovative learning environments.

Kishimoto previously worked as the superintendent and CEO of Gilbert Public Schools in Arizona and says Hawaii’s interest in school empowerment was what drew her to the Islands. Around the nation, communities generally aren’t ready to engage in a distributed leadership model, she says, because empowering school principals and their teams means other people have to give up some decision-making power – and that includes the superintendent. Kishimoto emphasizes that she too must do her job differently.

She’s already started those changes. For instance, in the past year, she’s moved $13 million of the DOE’s professional development funds to the complex area level. Complex areas are clusters of adjacent high schools and their feeder elementary and middle schools. Schools and their complex area superintendents – instead of the state office – now decide how they want to use more of the department’s professional development funds. And last school year, the department created $1 million worth of innovation grants that traditional and charter schools could apply for to implement creative practices.

Ige says changes like the DOE’s innovation grants have encouraged a culture within the department that values innovation and school level ownership of curriculum and programs. Schools are already innovating their learning practices and teaching approaches. Much of that takes the shape of learning that is student-centered and relevant to the real world, and emphasizes skill building.

“What we’ve learned, and we’ve seen when we listen to student voice and we challenge students, is that they often exceed our expectations of what they can do,” Ige says. “I think that it’s really creating a system that can support the students and let them achieve to their level because they are so committed to taking on the challenges that many of us would think they are not capable of, but they have demonstrated over and over and over again that they can.”

Such student-centered learning often presents itself in project-based and work-based learning – examples of which can be seen across the state. Terrence George, president and CEO of the Harold K.L. Castle Foundation, which invests in education initiatives, describes what he sees as the best approach: “I think that the work related to project-based learning, school redesign, empowerment and innovation that is student-centered, rigorous, connected to (the) real world that the kids will inhabit when they graduate is our recipe for success.”

Relevant Experiences

On a breezy Monday afternoon, a group of students at SEEQS, the charter school focused on sustainability, are tending to cilantro and lettuce plants growing in their aquaponics and hydroponics systems. A few feet away, another group uses power tools to build a farm stand. These students are preparing for public exhibitions later in the week. Their job will be to present projects exploring the relationship between food and community to their families and the public.

Cushman-Patz founded the school in 2013 and centered its instruction on community-focused, project-based, interdisciplinary learning experiences with a focus on sustainability. The hands-on aspect of the school resulted from her own schooling, which she says did not prepare her for life.

Four days a week, students at SEEQS dedicate 115 minutes – a little more than a quarter of the entire school day – to work on projects related to their Essential Question of Sustainability, or EQS. Depending on the quarter, students might be working on teacher-led or individual or group projects relating to their question. SEEQS serves about 180 students in grades six through eight, so the school’s job, Cushman-Patz says, is to teach students about the project process of proposing an idea, receiving feedback, making iterations, presenting their work and making further improvements. Each EQS course is composed of 60 students and is co-taught by English, science, history, math and art teachers, so students can incorporate skills and tools from each discipline into their projects.

These students are engaged in project-based learning. The definition of project-based learning varies, but Mireles, of PBLWorks, defines it as a teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by investigating and responding to authentic, engaging and complex questions, problems or challenges. Students work on these projects for an extended time and have opportunities to continually reflect and improve their work, and they produce a public product. The organization provides training in project-based learning for schools and teachers. In 2018, PBLWorks reached more than 30,000 teachers and provided workshops and services across all 50 states.

Project-based learning is often lauded as an effective way to engage students in hands-on learning that’s relevant to their interests or experiences in the real world. By completing projects like designing a logo for a local business or creating a video public service announcement, students build knowledge in subject areas as well as skills in communication, collaboration and critical thinking – skills that employers want, says Candy Suiso, program director of Searider Productions, Waianae High School’s multimedia program.

In August, Hana High and Elementary School launched a nontraditional campus at Hana Bay for 16 high schoolers who were interested in interdisciplinary and hands-on learning. Their first project was to build the structures for their campus, including an open-air pavilion and computer lab. The purpose of this nontraditional school, says former principal Rick Paul, is to better integrate the real world with the classroom. The hands-on activities come first, says Rick Rutiz, executive director of Ma Ka Hana Ka Ike, the nonprofit vocational training program that the school teamed up with to launch the project. For example, math can be taught using canoe paddling or by going to a loi to figure out how much water runs through it in a certain time.

Students from Ma Ka Hana Ka Ike calculate water flow in an East Maui loi kalo | Photo: Courtesy of Kirsten Whatley, Ma Ka Hana Ka Ike

Paul says one challenge of project-based learning is giving grades based on DOE requirements, which segment graduation credits and standards by subject, like English, science and math. “What’s difficult is to build a pretty fancy building or structure and then say, ‘I can give you a grade in Algebra 1.’ Because all those Algebra 1 standards aren’t (met in that project). But there is some Algebra 1, some Algebra 2, there’s some of everything,” he says.

Rutiz says another challenge is motivating the 16 students to engage with their learning and step up in an environment where they’re not given worksheets and not told what to do all the time. This nontraditional school, however, is an experiment and elements of it will likely be incorporated into the whole school later.

“The renegade thing was to try to demonstrate to others in Hawaii education that you take these kids who don’t do well in a four-walled classroom and you put them in a different situation, and they will excel and do great things,” he says. “They won’t be absent 25 percent of the time. They won’t have 40 referrals in a year. They won’t be in the same situation they were the year before.”

He adds that he’s not saying Hawaii needs to throw out its education system, but it is the responsibility of educators to do better and try new things.

“We’re making the kids spend all the years – (when they are) 15, 16, 17, 18 – when kids should be on fire, just ‘Whoa, how do you do this?’ ‘Show me how to do this.’ ‘How can I turn this upside down?’ ‘There’s got to be a better way to do that.’ That’s how they should be spending these years. And they’re not; they’re alienated,” he says. “They’re saying – excuse my language – but ‘What the f— am I doing here?’ We’ve got to find a way to … inspire and to motivate.”

Mireles says she’s seen project-based learning grow in the 15 years she’s been in the Islands. Project-based learning is the foundation of several charter schools – such as those that focus on Hawaiian culture-based education. Several years ago, PBLWorks (formerly the Buck Institute for Education) and the Harold K.L. Castle Foundation teamed up to launch the Hawaii Innovative Leaders Network, a project that trained and supported two cohorts of public and charter school principals to create school cultures in which project-based learning was encouraged. Another two HILN cohorts are expected to begin this year, according to Alex Harris, the Castle Foundation’s senior education advisor.

A lot of the project-based learning happening at schools on Kauai’s west side resulted from this network, says Melissa Speetjens, principal of Waimea Canyon Middle School. This year, her school is implementing a new bell schedule that dedicates 20 percent of the school day for project-based learning – fueled by a DOE innovation grant.

PBLWorks and Castle Foundation are also working on another, larger, multiyear project to train educators in the Pearl City-Waipahu high schools complex area. (The project also targets the Manchester School District in New Hampshire.) The goal is to scale high quality project-based learning in the complex area so all classrooms conduct at least two projects a year. So far, 315 Pearl City-Waipahu teachers and school leaders from 10 schools have been trained, says complex area superintendent Keith Hui. Outside of this project, about 1,120 Hawaii teachers have participated in PBLWorks’ Project-Based Learning 101 training since 2012.

Real-World Learning

Scroll through Searider Productions’ Vimeo page and you’ll find about 800 skillfully crafted videos ranging from news stories about the Waianae community to advertisements for nearby organizations to public service announcements – and they’re all produced by students.

Waianae High’s multimedia program was established in 1993 as a way to keep students in school and make learning fun and relevant, says Suiso, who co-founded the program. Today, students can pursue pathways in photography, video production, graphic arts or journalism, and they’re employable by the time they graduate because they’ve already developed many of the skills needed for these fields, she says.

Nicholas Smith was in Searider Productions for four years and graduated from the high school in 2004. He now works at the Institute for Native Pacific Education and Culture (InPeace) as director of communications and says he wouldn’t be doing what he does today if not for the program, which offers skills that Waianae students would otherwise have to travel to learn.

“To allow students to find their purpose and passion, we need to give them room to explore different careers, to do learning in teams on issues that are relevant to them, to make the learning of basic content, like writing a persuasive essay or doing algebra, to apply that to things that matter to kids,” says George of the Castle Foundation.

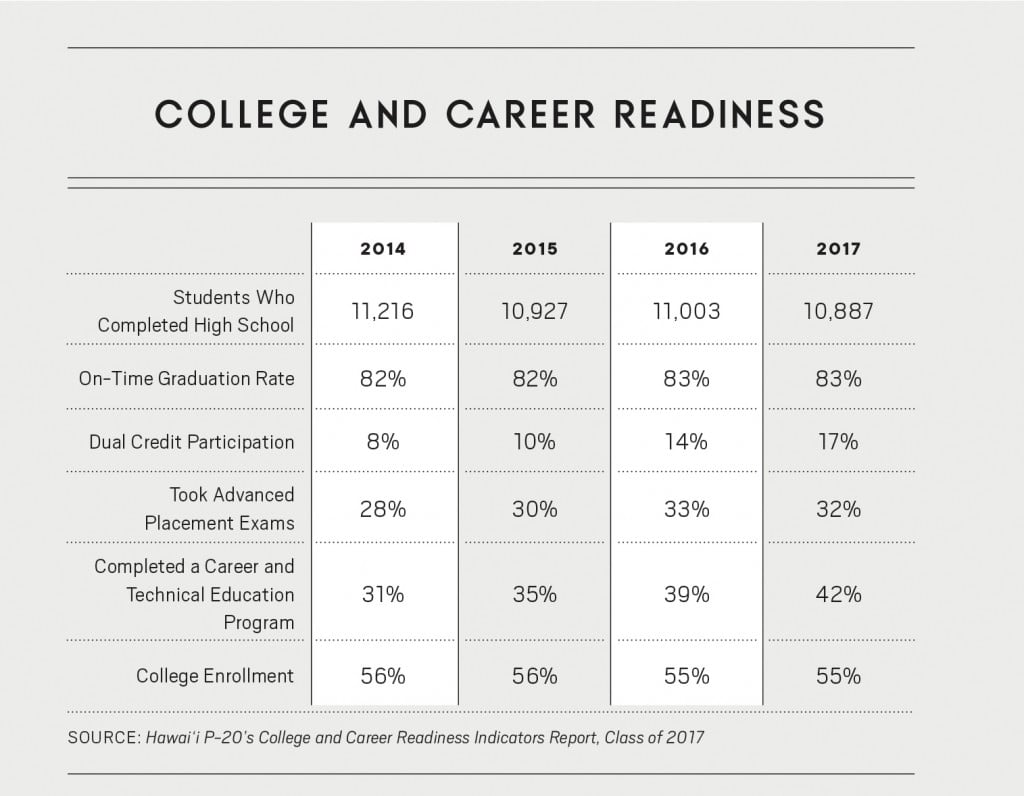

This work is often seen in Career and Technical Education programs that allow public high school students to explore careers. There are six CTE pathways, each with more specific programs of study; for example, the Arts and Communication pathway features a program focusing on animation. Each pathway is made up of a sequence of courses and spans at least two years of high school and into postsecondary education. The number of students completing a CTE sequence of courses has grown over the last four years. Almost a third of the class of 2014 statewide completed a CTE program; for the class of 2017, that number was 42 percent, according to data from Hawaii P-20 Partnerships for Education, a statewide effort led by the DOE, UH and the Executive Office on Early Learning.

“When students are in high school and they see high school as something they have to do before they get to college and then they see college as something they have to do before they get a job, then it’s a real slog along the way. Whereas if they can see ‘Hey I want to be an auto mechanic, here’s my path to get there,’ that can be inspiring,” says Stephen Schatz, executive director of Hawaii P-20.

At Waipahu High School, the CTE programs are housed in five career academies, where coursework is grouped and sequenced into programs of study that prepare students for particular career fields while also bringing in real-life experiences. Fifteen DOE high schools have career academies. Waipahu High’s principal, Keith Hayashi, says some of Waipahu’s academies have been around for 25 years, giving students voice and ownership over their learning as they figure out what their passions are. The school’s motto, after all, is “My Voice, My Choice, My Future.”

The school’s Academy of Professional and Public Services helped senior Christine Alonzo decide to pursue a career in accounting and has provided her with valuable real-world experience in the field. Through the academy, she’s volunteered for Leeward Community College’s Volunteer Income Tax Assistance Program, which helps low-income people prepare taxes, and she’s interned with HawaiiUSA Federal Credit Union.

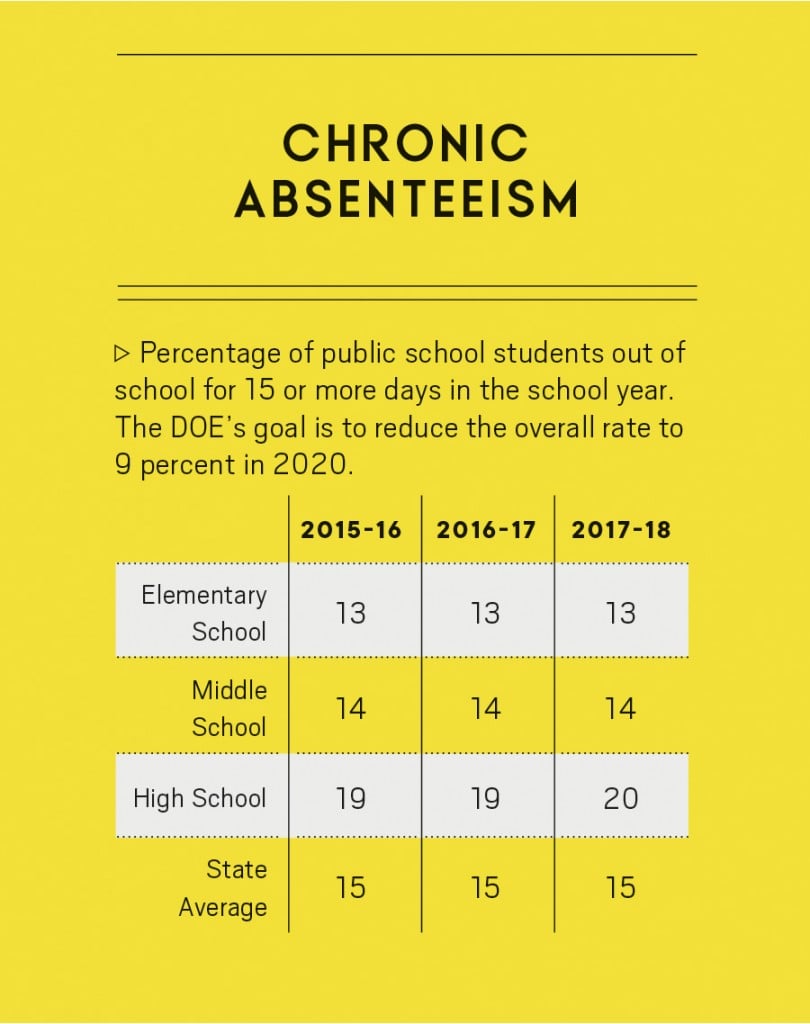

Daniel Hamada, who just retired after eight years as principal of Kapaa High School, says the purpose of school is to provide education that’s relevant, rigorous and built on relationships with teachers. During his first year he saw that school was not that relevant for the students: 12 percent of the freshman class was chronically absent, a third were getting D’s and F’s, and about 20 percent weren’t progressing into 10th grade. Since then, career academies have been created to better connect students to support and make their learning relevant. Freshmen are grouped into one of two hui where a team of teachers builds relationships with them and helps them transition into high school. And in their sophomore year, they enter one of two career academies – one focused on service careers, like health service and culinary, and the other on design-related careers, like building, business and digital media.

The school’s transformation has meant fewer ninth-graders are held back from 10th grade and a lower chronic absenteeism rate, Hamada says. Students in the class of 2018, for example, maintained attendance rates ranging from 89 to 93 percent throughout their four years at the school, and each year most students passed core academic classes such as math, English and science.

“Today’s generation, they know what’s out there, they know about what they’re interested in; now we just have to provide an environment for them to help find their way,” Hamada says, adding that building partnerships with the community and businesses is important too. For example, students interested in teaching can tutor at a nearby elementary school, and students interested in health care can shadow workers at a nearby hospital. And the high school is looking at providing access to industry certifications.

Waipahu High School already does this for some of its pathways. Students can be certified as food handlers, pharmacy technicians and medical assistants, and for software like SolidWorks and Revit, which are used by engineers, architects, contractors and designers – and the school is looking to expand its certifications as it continues to partner with industry, Hayashi says. This year, the school principal estimates about 158 certifications will be earned by students across the different academies.

Kishimoto says the involvement of industry in career academies is pushing the design of instruction and learning in a different direction, where learning spaces include the community and teachers work alongside industry experts. Business leaders are excited about helping schools shift from a content-focus to a skills-focus, says the Castle Foundation’s George, who is also co-chair of the Hawaii Executive Conference’s education committee, which provides industry perspective and support to education. He adds there’s alignment between employers, students and educators that he hasn’t seen in a while.

On Kauai, the Keiki to Career initiative is helping to bridge the gap between public schools and industry by creating academy coordinator positions at each of the three high schools to coordinate work-based learning experiences, like bringing in guest speakers and creating teacher “externships” so educators can learn about current trends in industry. The initiative is also creating islandwide advisory boards composed of leaders from businesses, the DOE and Kauai Community College, says Dana Hazelton, director of Keiki to Career’s Career Connections.

It Takes a Village

“Never in my whole life have I been more excited about public education anywhere than now – and it’s in Hawaii,” says Reppun, a former teacher who is now a specialist at Apple and organizes discussions centered on screenings of the 2015 education-reform documentary, “Most Likely to Succeed.”

Several sources interviewed for this story agree with him. There’s a lot of collaboration occurring among public, private and charter schools – all trying to figure out how to move education forward in the 21st century. Dintersmith, the education change agent and executive producer of “Most Likely to Succeed,” says Hawaii’s level of collaboration exceeds that in any other state.

It’s been a long journey to get to where education is today, says Hamada, the retired Kapaa High principal. “We have to take this upon ourselves to now innovate and partner, to make this happen. So in the most positive ways, it’s our kuleana, our responsibility, to really make it happen.”

Superintendent Kishimoto says she’s excited to see so much energy behind this movement. She’ll often receive emails from teachers telling her about the innovative things they’ve recently done in their classrooms. “It’s not going to be led by the state. I can set vision. I can set direction. And I can provide resources and advocate at the Legislature for the resources we need,” she says. “But the rest of the work happens at the school level. The exciting work happens there.”

━━

Part 2: Student Success

As Schools Change, So Do Measures of Student Success

Standardized tests. Those words invoke memories of students sitting in rows of desks, heads down, filling in bubbles on a multiple-choice test.

For a long time, those tests largely determined whether schools and students were considered successful. They’re still important for measuring student performance, but there’s recognition today that these tests do not reveal all of what students know.

Schools and the state Department of Education are rethinking what student success should look like and how it should be measured. That rethinking is taking place at the same time that more power, money and decisions are being shifted from DOE headquarters to the schools, as educators are encouraged to innovate and as students learn more and more with hands-on projects.

“We also have to start looking at what are some other ways to measure student growth and gains in terms of achievement because a standardized exam is not going to measure hands-on learning opportunities and it’s not going to necessarily measure the students’ ability to gain knowledge on their own and think differently unless it is directly aligned to particular items on an exam,” says Christina Kishimoto, superintendent of the DOE.

Tests Are Not Everything

Cynthia Tong, an 8th grade social studies teacher at Ewa Makai Middle School, has been teaching for 23 years. One year at Waipahu Intermediate, she estimates, students spent 13 whole school days taking standardized tests.

Students are under a lot of pressure to do well on these tests, she says. “I see more kids sick, crying, a sense of helplessness, hopelessness, when we have testing, no matter how much we try to buff them up and tell them that they’re good and we practice for the test,” she says.

Standardized tests were the primary focuses of many public schools for years. Federal mandates under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 pushed schools to improve their test scores each year or be labeled as failing. 2010’s Race to the Top further encouraged the testing culture.

“It’s very hard for teachers and for principals, too, I think, when you’re being judged on these scores to not push your kids to be good test takers, which is not the best way to educate children,” says Catherine Payne, chair of the Board of Education.

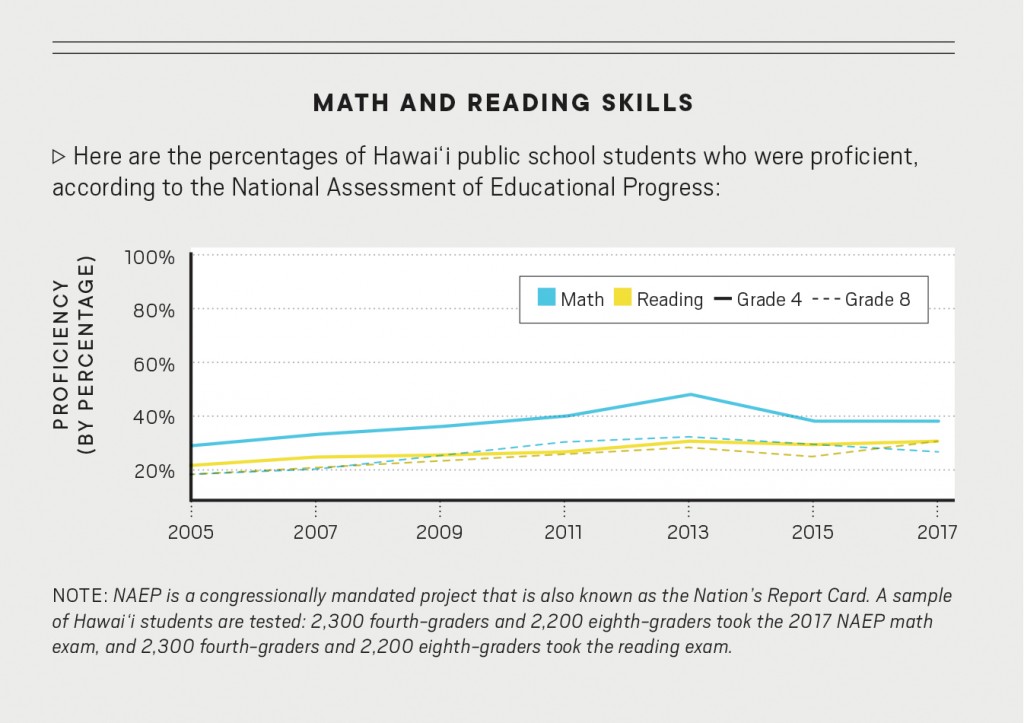

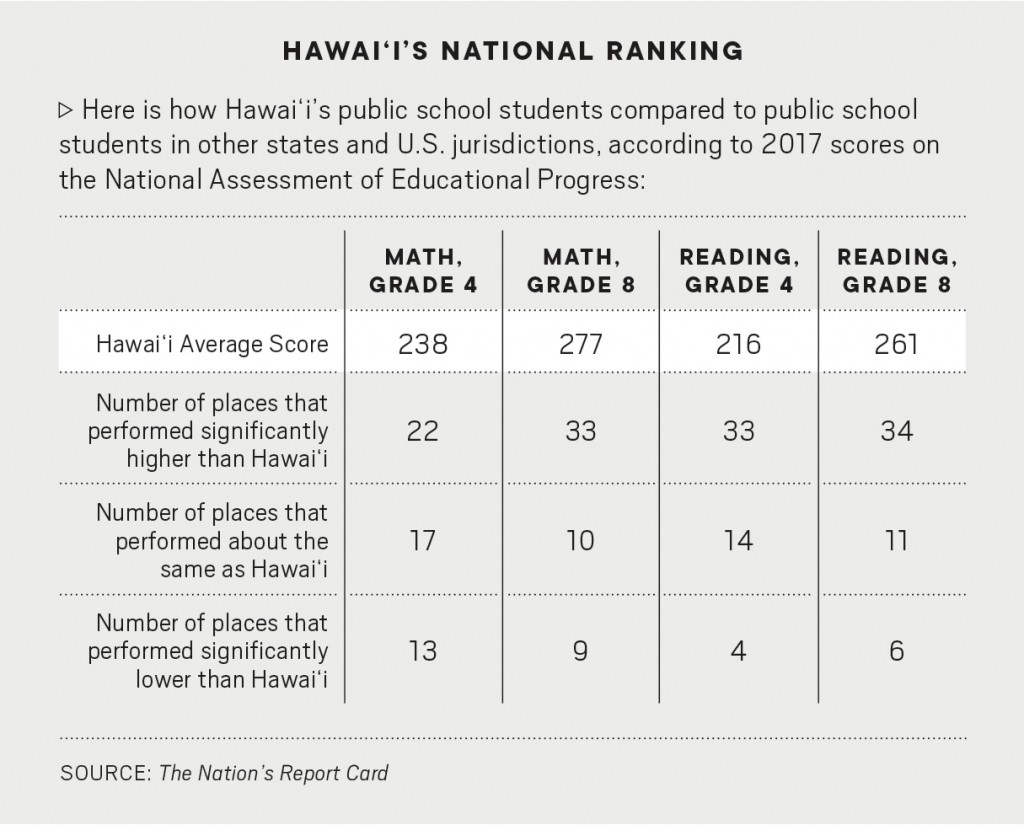

Today, federal law requires students to be tested in certain grades in English, math and science. Hawaii also requires 11th graders to take the ACT, and every other year a sample of 4th and 8th graders take the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Reading and Math. The state DOE also administers statewide tests for English language proficiency and for students in its Hawaiian immersion program.

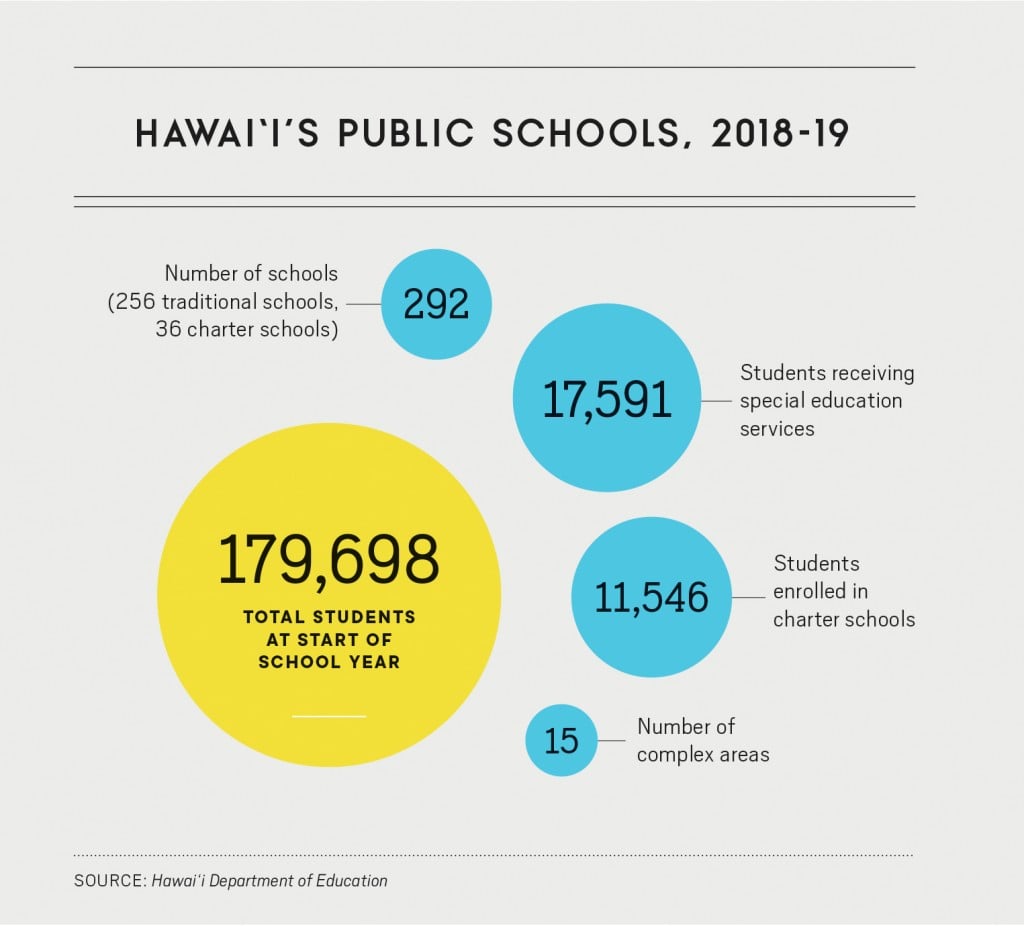

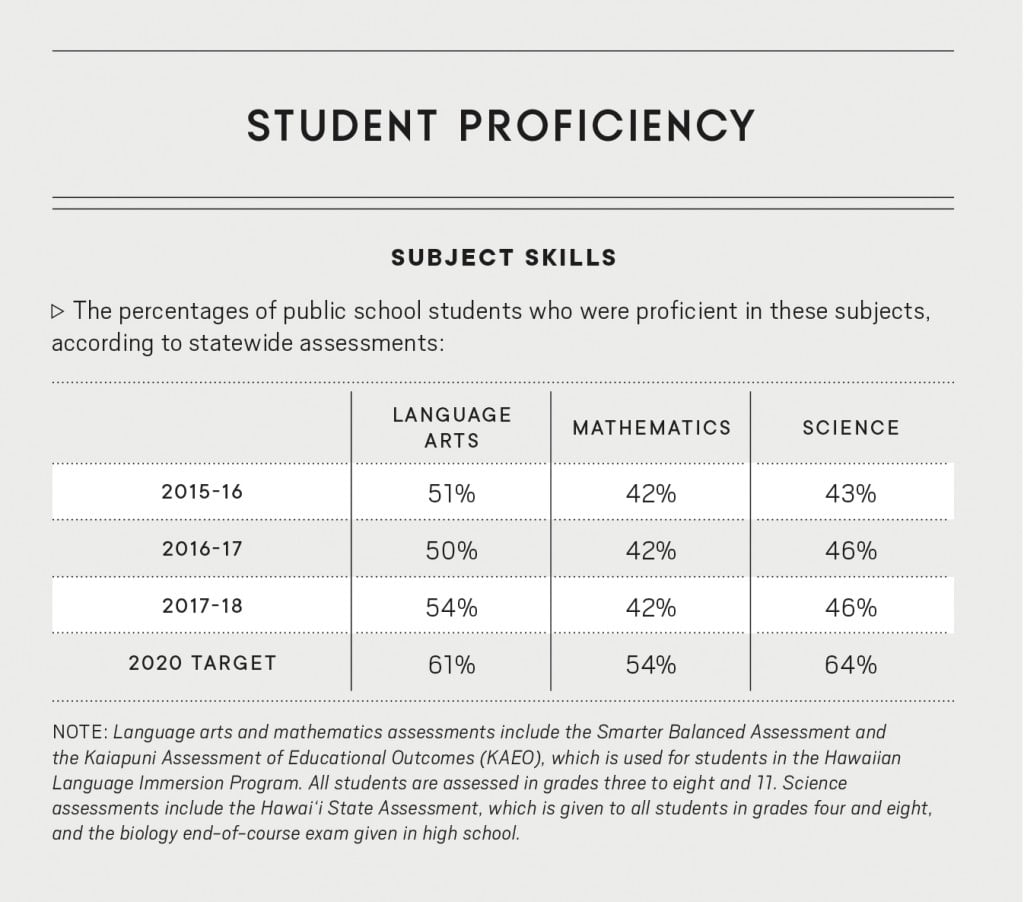

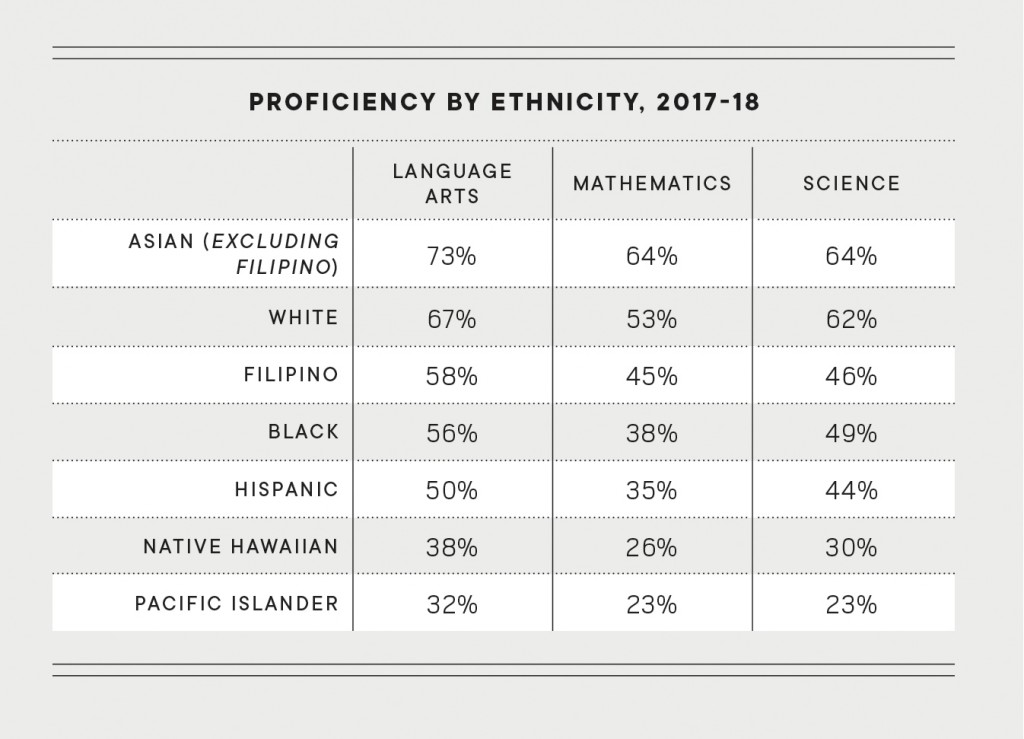

Students’ scores on the statewide assessments for math and science have remained relatively consistent for the last three years. In 2017-18, 42 percent of students were proficient in math, and 46 percent were proficient in science. And language arts scores grew by 4 percentage points, from 50 percent of students proficient in 2016-17 to 54 percent in 2017-18.

Under No Child Left Behind, school performance was measured mostly by test scores. Today, the Strive HI school accountability system measures school performance using multiple indicators such as student achievement, chronic absenteeism, high school graduation rates, college enrollment and the achievement gap between special needs students and other students.

Educators agree that standardized tests are an important measure of whether students are learning – but they’re not the only indicator.

Buffy Cushman-Patz is the school leader of the School for Examining Essential Questions of Sustainability. The Honolulu-based charter school focuses on interdisciplinary, real world, project-based learning that’s rooted in sustainability. Her students have outperformed the state test score averages in every subject and grade for several years, but what matters more, she says, are the quality of their projects, exhibitions and portfolio defenses and whether students are able to reflect on their learning.

“What I want is to walk through campus and see happy kids, I want to see smiles on their faces, I want to see them engaged with me, I want to see them engaged with you, I want to see them be able to talk about what they’re learning and why,” she says. “That’s how I measure the success of our school, but those are not easily quantifiable.”

Pursuing Innovation

To flourish in the modern world, students need to graduate with skills in critical thinking, problem solving, communication, creativity and collaboration. Those are difficult skills to measure.

Hawaii will be applying for the “innovative assessments” pilot program under 2015’s Every Student Succeeds Act – which replaced No Child Left Behind and provides states with more flexibility to design their education systems. Under the program, Hawaii will be able to develop, pilot and scale innovative assessments instead of the current standardized tests.

Innovative assessments should provide a richer story about what students can do and how they’re growing. Rodney Luke, assistant superintendent for the DOE’s Office of Strategy, Innovation and Performance, says the state is still working on its plan for what its innovative assessment system might look like and how it will be implemented, but innovative assessments could be authentic, problem-based, project-based or performance-based. Here are some examples of how innovative assessments are already being used in Hawaii’s public schools.

Authentic assessments are assessments in which students demonstrate and apply skills and knowledge by performing real world tasks. Tong does authentic assessments in her 8th grade social studies classes at Ewa Makai Middle School and says she sees students engage more with their learning because they see the connection to the real world. For History Day, students’ projects might involve making documentaries, doing live action performances and creating websites – things that students could get a job doing in the real world, she says.

“Anytime you do an authentic assessment, you have leaps and bounds in learning of skill because it’s bundled together and they’re real, they make sense, they go together. When they’re separated out too far – they’re not within an authentic assessment – kids don’t learn it that fast, they don’t learn it very well, and they don’t commit it to memory,” she says. “But if they’re forced to read a story to a two-year-old and explain every word, that’s an authentic assessment.”

Innovative assessments are typically seen in pockets in Hawaii’s public schools. Some schools require senior projects where students pick a topic, do research, work with a mentor and present their learning experiences in front of community members. Or some teachers, like Tong, do them just in their classes.

Payne, who used to serve as the chair of the State Public Charter School Commission, says local charter schools are leading the way in developing innovative assessments.

Students from Malama Honua Charter School Fall Hoike Hula at Waimanalo Hawaiian Homes Halau 2014 | Photo: Courtesy of Malama Honua

At Hawaiian-focused charter schools like Malama Honua Charter School in Waimanalo, performance assessments are often used to gauge student learning, says Denise Espania, the school’s director. The school and 16 other Hawaiian-focused charters are working on culturally relevant assessments. Over the last several years, the group has developed a framework and toolkit for schools to use to assess student growth.

One example of performance assessments at Malama Honua are hoike, or public presentations of learning, which students do each trimester. During the first trimester’s hoike, students share with families a story they wrote or an image they drew that represents who they are and where they came from. In addition, students also give defenses of their learning, sharing with community members and experts what they’ve learned and what they think is important. Espania says these types of assessments are far more powerful than taking a fill-in-the-blank test.

“I’m hoping Hawaii can be part of this movement that believes in our students, that believes in our children, that they can and they do these amazingly rich rigorous assessments and that we’re, as a community, as a state, we are recognizing those as valuable forms of assessment,” she says.

(View Hawaii Business’ past coverage of authentic assessments.)

Reaching Different Learners

As schools and the system talk about redefining how students are measured, sources agree there’s still a need to make sure that all types of learners are engaged in their learning.

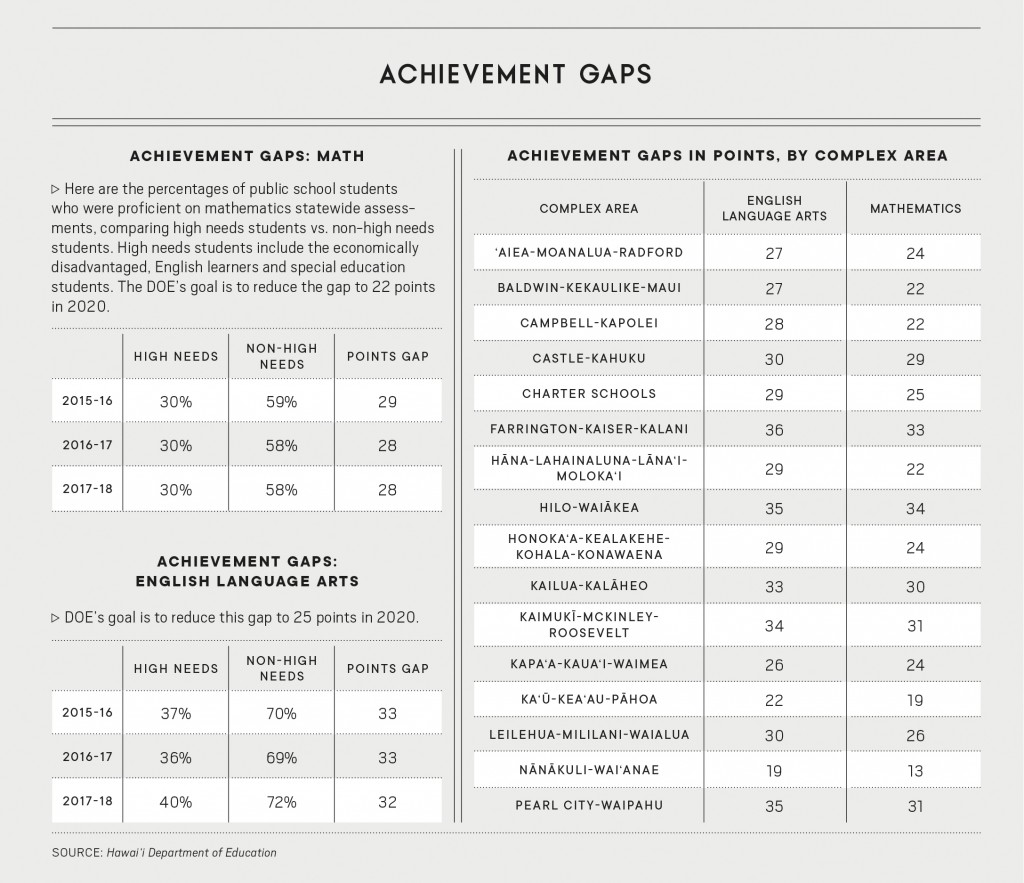

Hawaii’s achievement gaps between high needs and non-high needs students have remained consistent over the last three years. High needs students include students who receive special education services, who are economically disadvantaged or who are English language learners. In school year 2017-18, the gap between high needs and non-high needs students was 28 points in math and 32 points in language arts. The DOE’s goal is to reduce the math gap by six points and the language arts gap by seven points by 2020.

Tong of Ewa Makai Middle School thinks the achievement gap exists because of standardized tests. Not every learner is best fitted for taking multiple choice tests or learning in the same way. In addition, standardized tests tell students that only reading and math are important – and if they don’t do well in those areas, they won’t do well in others. That ignores the fact that students are great at other subjects, like science, physical education and music, she says.

In her class, she tries to close the achievement gap and engage all learners by teaching and assessing in different ways. For example, instead of always having multiple choice tests, essays or worksheets, she might ask her students to do a vertical learning discussion, create a thinking map or draw a cartoon.

“There’s lots of different ways to get at judging how kids learn, but the fallback has always been writing and reading, and that’s not fair to the kids,” she says. “A lot of our kids are strongly visual learners or strongly musical learners, so they might write a rap song or decide to do a skit, they might do a performance. I’ve even had kids who have created a video game or they created a board game to demonstrate what they knew about the Civil War.”

Getting creative in assessing and teaching can also help students who are struggling in a subject like math. A smaller percentage of Native Hawaiian students are proficient in statewide math tests than most other ethnic groups. Maya Chong, a K-5 curriculum coach at Kanu o Ka Aina, a Hawaiian-focused charter school in Waimea, says these test scores show Native Hawaiian students lack confidence in math. She says at her school in particular, students have trouble seeing why algebra or trigonometry are relevant.

“I think they see math as much more western than it is cultural. So bringing those two worlds together and also having practical application and showing them this math problem that is so black and white on paper or on a computer screen when they’re taking a test, just means this, like remember when we went out and we did this outside with our hands,” she says.

“I think they see math as much more western than it is cultural. So bringing those two worlds together and also having practical application and showing them this math problem that is so black and white on paper or on a computer screen when they’re taking a test, just means this, like remember when we went out and we did this outside with our hands,” she says.

This past summer, she and two other teachers at Hawaiian-focused charter schools on Kauai and in Hilo each developed 30 Hawaiian culture-based math lessons. They’re operating as part of the Kanaeokana network made up of Hawaiian immersion schools, culture-based charter schools, the UH community, DOE programs and community-based nonprofits, with support from Kamehameha Schools.

This year she’s helping to implement the lessons she created for kindergarten students. One unit focused on measurements, so students measured objects in the school’s garden. Another unit focused on geometry, so students identified shapes on kapa. Once students have a firm understanding of the different shapes, another lesson will involve them creating their own kapa.

Chong says students are better retaining the math concepts that are being taught. The next step, she adds, is to get more teachers involved. Eventually, the goal is to have teachers across all grade levels developing culturally relevant math lessons.

Providing support to students is another way to help them succeed in school. Kapolei High School opened its Hoola Leadership Academy in Fall 2008 as an alternative learning program to help struggling students. The name means “to heal,” and the program was meant to offer prevention and intervention so students could successfully progress through high school in a family style environment, says Joan Lewis, who was one of the founders and is now an instructional coach at the school.

Today, the program has about 200 students in 9th through 12th grade. It’s one of the school’s academies and provides curriculum centered on Hawaiian culture and natural resources. Students often work on hands-on projects, like developing climate-appropriate landscaping and produce, and offering solutions for consideration to issues like homelessness, waste management and bullying.

The key, Lewis says, is providing students with support as well as opportunities for them to apply their learning and helping them to identify their personal strengths. “… What it comes down to is giving them the time, the space, the direction, the redirection to find who they really are and what their gifts are for themselves and for us as a program and a school but for their community,” she says.

She adds that the students that are in Hoola and other similar learning programs are typically the ones who have historically asked teachers over and over why they need to know what they’re teaching. “Our students push us to make sure we stay relevant and we can explain thoroughly the purpose of it, how they’re going to use it, why it matters, whatever you want to think, and then once our kids get into it and see what comes of their work, they’re hungry for what comes next.”

━━

Part 3a: Trying to Solve the Teacher Shortage

Students in schools with high turnover ask if their teachers are going to finish the school year so often that there’s a term for it: “Gone by December.”

“That was a story that I have heard from students who didn’t believe the teachers would be staying for very long in these areas,” says Corey Rosenlee, president of the Hawaii State Teachers Association. “But we do know that there are teachers who leave during the year. … I’ve seen teachers at Campbell High School who just stayed a couple of months.”

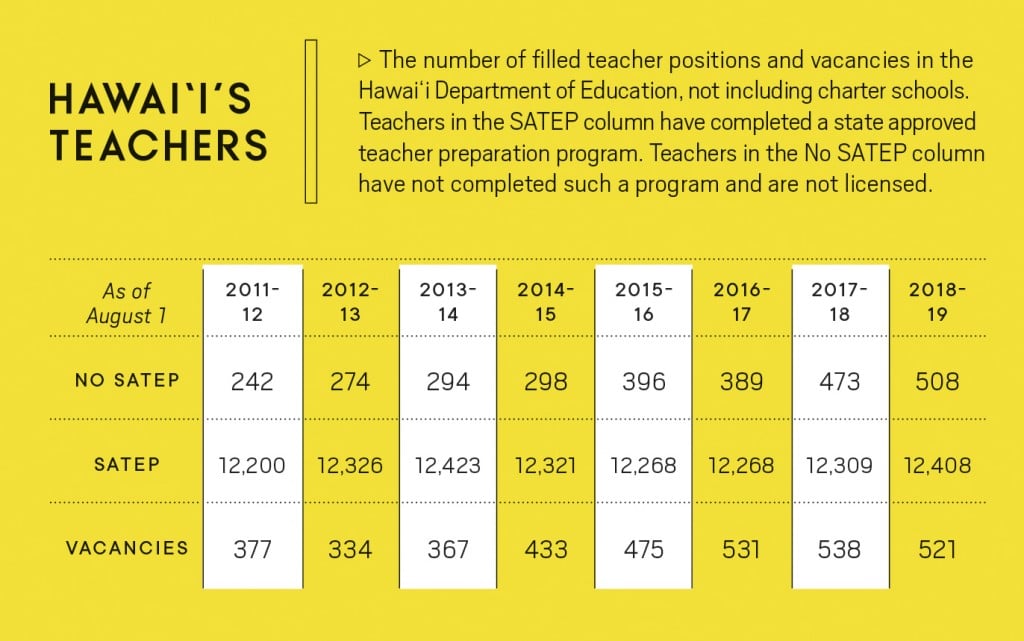

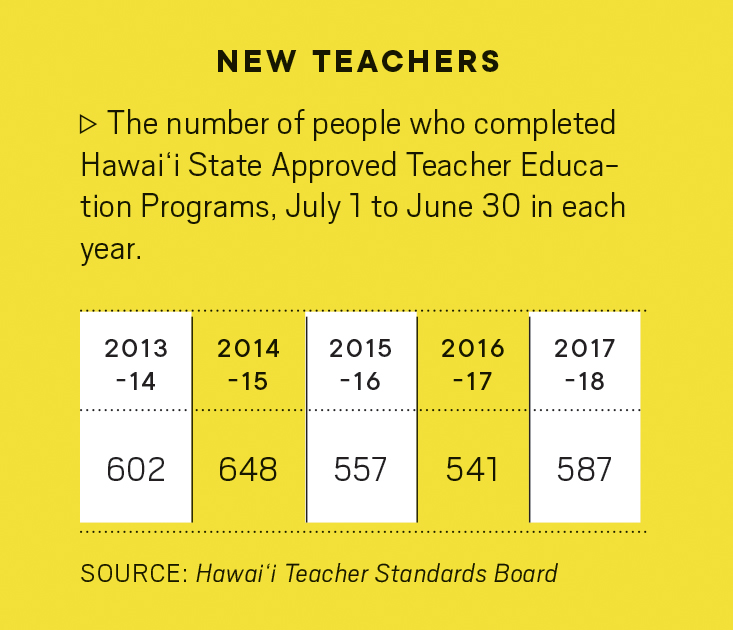

The challenges of finding and retaining teachers have long been exacerbated by the Islands’ isolation and high cost of living. Every year, the state Department of Education hires an average of 1,200 new teachers – about 9 percent of the department’s 13,000 teaching positions – to replace those who have retired or resigned.

Many of these positions are filled by residents, but local teacher preparation programs aren’t graduating enough teacher candidates to keep up with demand. The solution, then, has typically been to recruit teachers from the Mainland, but because they’re often placed in the most remote areas – where they find it hard to put down roots – they tend to only fill the gaps temporarily, says Catherine Payne, chair of the state Board of Education.

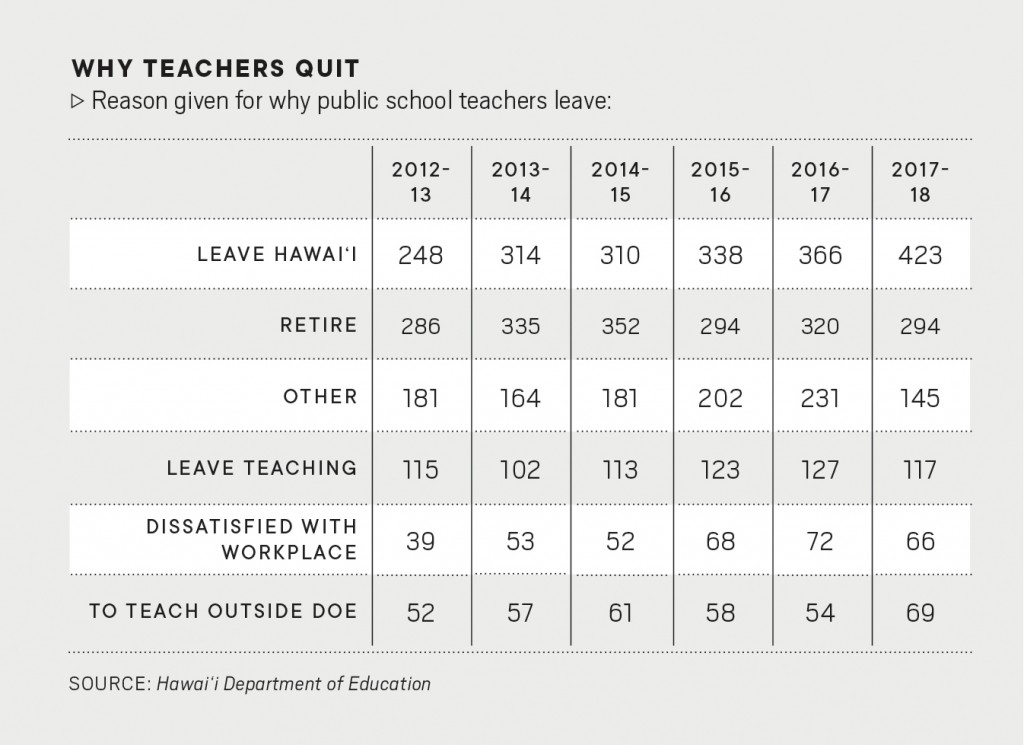

According to the DOE’s 2017-18 Employment Report, the number of public school teachers leaving the Islands has increased 71 percent, compared to 2012-13. More teachers are leaving Hawaii than retiring. As the state’s teacher shortage drags on, the number of teacher positions filled by uncertified teachers continues to climb. And more than 500 teaching positions continue to be unfilled at the beginning of the school year each August.

“What we’re experiencing is that we have a lot of schools that do not have qualified teachers in the classroom. We have long-term subs, and some are very good – some of them are retired teachers who are coming back – but you cannot fill the system around an unstable teaching force,” Payne says.

“This is where equity comes in, because even though Honolulu has some problems, the most serious problems are in the areas where you have the most struggling students. And to say we’re going to be OK with giving them the lower qualified teachers is not an acceptable response.”

Solving Hawaii’s teacher shortage will take a multifaceted approach, several sources agree. That includes things like increasing teacher pay, improving the public’s perception of the teaching profession and thinking outside of the box. Here’s a look at some potential solutions.

Locally Grown

“We’ve got to do our best to making teaching cool again,” says Stephen Schatz, executive director of Hawaii P-20 Partnerships for Education. “We really want our kids to grow up and realize what a great profession it is.”

In November, Hawaii P-20 convened a meeting with representatives of the Chamber of Commerce Hawaii, local teacher preparation programs, and public, private and charter schools to talk about ways to address the teacher shortage. Schatz says there’s a lot of energy around getting students interested in teaching when they’re in high school or younger.

“At the end of the day we’re recruiting about a thousand teachers here (a year), and locally we’re not producing a thousand teachers, so there’s just a simple supply and demand mismatch,” he says.

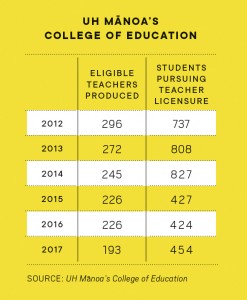

Over the years, UH Manoa’s College of Education has seen a decline in both the number of students pursuing teacher licensure and the number of eligible teachers it produces. In 2012, the COE produced 296 eligible teachers; in 2017, 193. Nathan Murata, dean of UH Manoa’s COE, says that’s a trend seen at other education colleges around the country.

Various programs exist to encourage keiki to become teachers. Several high schools have teacher academies or programs of study that give students exposure to the profession. COE partners with academies at Waipahu, Farrington, Waianae and Campbell high schools to bring them to the UH Manoa campus, so high schoolers can observe COE classrooms and ask faculty questions, says Denise Nakaoka, director of student academic services for the COE, adding that the college wants to expand its outreach to more high schools. In addition, COE is starting to recruit in middle schools.

In 2017, UH launched its Be a Hero, Be a Teacher multimedia campaign to encourage working professionals and high school and college students to consider becoming teachers. Murata says that campaign resulted from conversations among UH administrators about the need to reimagine the teaching profession and improve the perception of what it means to be a teacher. Many people are deterred by the low pay, he says.

In 2017, UH launched its Be a Hero, Be a Teacher multimedia campaign to encourage working professionals and high school and college students to consider becoming teachers. Murata says that campaign resulted from conversations among UH administrators about the need to reimagine the teaching profession and improve the perception of what it means to be a teacher. Many people are deterred by the low pay, he says.

UH and the DOE are also looking at ways to help working professionals become teachers. Several years ago, state Sen. Michelle Kidani, who chairs the Senate Committee on Education, learned that a majority of Hawaii’s substitute teachers already had bachelor’s degrees, but not teaching degrees.

“I think at the time they figured out that we probably had 5,000, 6,000 substitute teachers. So you’re looking at a pool of probably about 2,800 teachers in the classroom who are substitutes and do not have teaching certificates,” she says. “So why not recruit from there?”

Today, Grow Our Own is a partnership between the state Department of Education and UH Manoa’s COE. The program targets educational assistants, emergency hires and substitute teachers who are already working in public secondary school classrooms. They work toward post-baccalaureate certificates in secondary education, which leads to teacher licensure, and their tuition is covered by funding from the state Legislature and the DOE.

Classes are delivered in an online/hybrid format, Nakaoka says, so participants can continue to work full time. Neighbor Island candidates can also receive stipends to attend required face-to-face meetings, she adds. Once they complete the program, participants must commit to three years of full-time teaching in grades 6-12 in charter or traditional public schools.

Classes are delivered in an online/hybrid format, Nakaoka says, so participants can continue to work full time. Neighbor Island candidates can also receive stipends to attend required face-to-face meetings, she adds. Once they complete the program, participants must commit to three years of full-time teaching in grades 6-12 in charter or traditional public schools.

The first cohort of 30 participants began taking courses in spring 2018. A second cohort of 17 participants began this January.

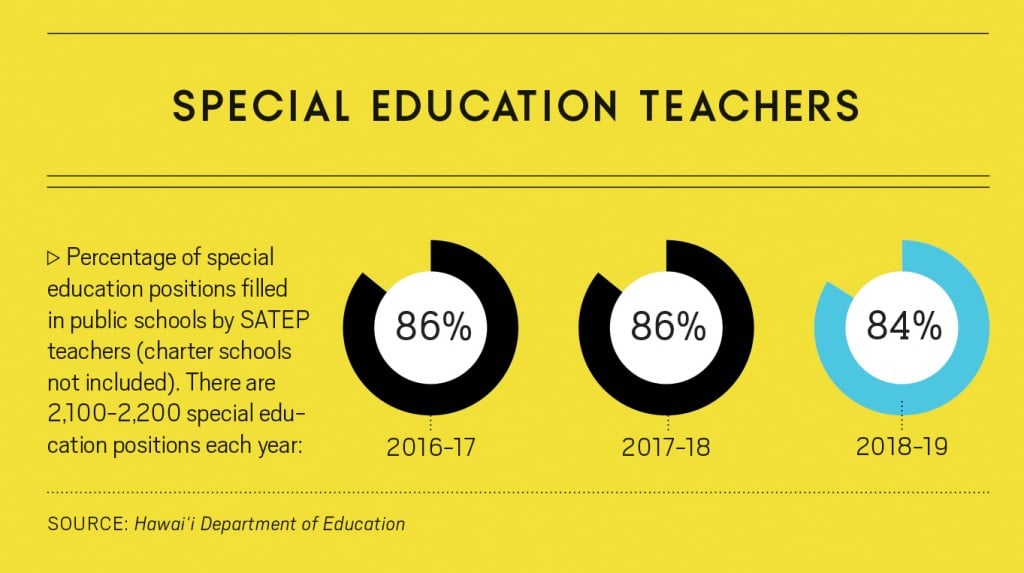

There are additional efforts underway to help increase Hawaii’s supply of teachers. Leeward Community College and the Institute for Native Pacific Education and Culture launched a pilot program in Nanakuli in fall 2018 to help educational assistants become special education teachers. Accelerated hybrid classes are held in Nanakuli and participants work towards a bachelor’s of science in special education. And in 2018, Kamehameha Schools launched its Hookawowo Scholarship for Native Hawaiian students pursuing education degrees. Eighty-three students received scholarships for this school year. Kanakolu Noa, manager of strategy development in Kamehameha’s Community Engagement and Resources Group, says the scholarship was created to help address the teacher shortage.

Addressing Teacher Pay

The teachers union has long argued that Hawaii’s low teacher salaries are the cause of its poor retention. HSTA’s Rosenlee says those salaries are the lowest in the nation when adjusted for cost of living. Currently, a starting teacher who’s certified and has a bachelor’s degree makes $49,100.

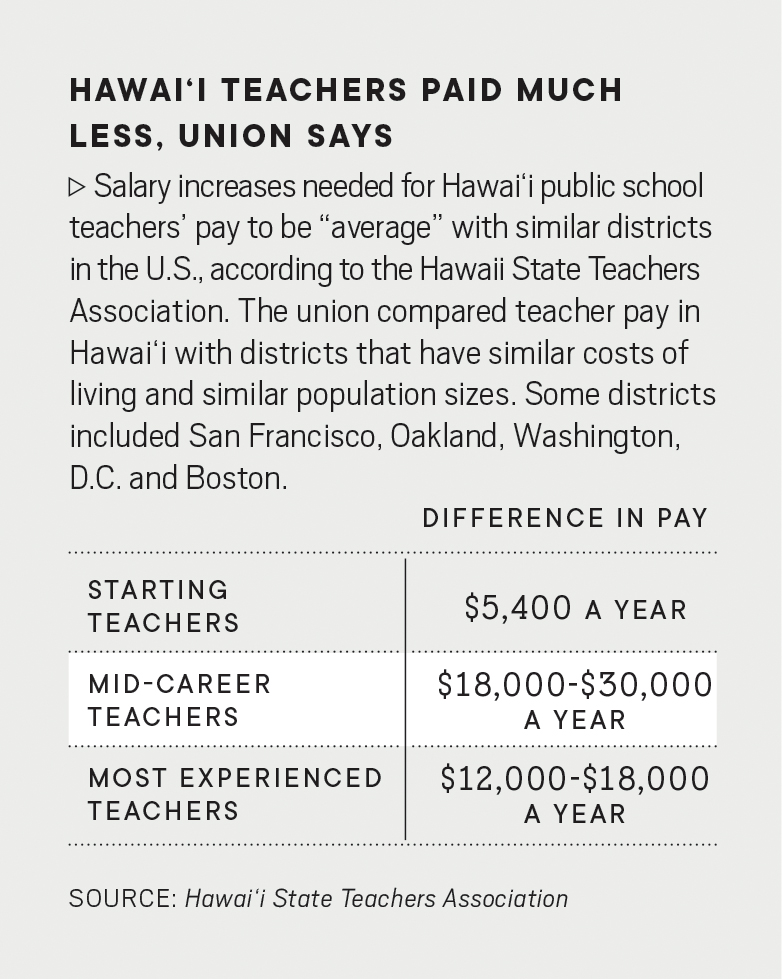

According to an analysis by HSTA, which looked at 10 Mainland districts with similar costs of living and population sizes, Hawaii’s starting teachers make about $5,400 less than their counterparts in comparable districts. The gap for midcareer teachers – those with 10 to 20 years of experience – is between $18,000 and $30,000, and the gap for the most experienced teachers is between $12,000 and $18,000. Those districts, Rosenlee says, compensate teachers based on years of experience, a practice not followed in Hawaii.

According to an analysis by HSTA, which looked at 10 Mainland districts with similar costs of living and population sizes, Hawaii’s starting teachers make about $5,400 less than their counterparts in comparable districts. The gap for midcareer teachers – those with 10 to 20 years of experience – is between $18,000 and $30,000, and the gap for the most experienced teachers is between $12,000 and $18,000. Those districts, Rosenlee says, compensate teachers based on years of experience, a practice not followed in Hawaii.

Currently, Hawaii’s teachers receive pay increases by accumulating DOE-approved professional development or academic credits, or through salary step increases, which have to be negotiated. Joan Lewis, an instructional coach at Kapolei High School and a former HSTA VP, says that means local teachers who have 10 years of experience could be making the same amount – or more, depending on the number of credits a teacher accumulates – as a teacher with 20 years of experience. That’s demoralizing to a veteran teacher, she adds.

HSTA’s suggestion is to pay teachers based on years of service, which would allow teachers to better plan their futures, like when they’ll be able to afford to buy a house, Rosenlee says. Lewis adds that annual step movements would also give teachers more confidence that their salaries will keep up with cost of living increases.

The DOE and Board of Education agree that teacher compensation needs to be addressed. Cynthia Covell of the DOE’s Office of Talent Management says the department is preparing to launch a study that will look at pay, incentives, bonuses and other benefits to give the department a better idea of what it needs to do to be competitive. Teacher and student voices will be included.

“As a state we need to make a decision about what competitive level we want to maintain in terms of teachers’ salaries with where salaries are nationally as adjusted for cost of living in Hawaii,” says Superintendent Christina Kishimoto. “And so you know, depending on what values are put into that, that can be we’re $30 million short all the way up to several hundred million dollars short, depending on the competitive level.”

She adds that the DOE isn’t just competing against other school districts for teachers. It’s also competing against other careers, such as those in math and STEM, that pay higher salaries. But the department currently doesn’t have enough funds to make teacher pay competitive. In 2018, HSTA advocated for a proposed constitutional amendment that, if approved by voters, would have allowed the state Legislature to use property taxes to help fund public education. The state Supreme Court invalidated the proposed amendment in October.

Several sources agree that increasing teachers’ pay is only part of the solution. Covell says of 822 exit survey responses for the 2017-18 school year, 13 people indicated they were dissatisfied with salary. She adds there are also discussions about teacher housing – the department currently only has 59 units in various states of repair – and housing stipends.

Rural Areas Get Creative

Many of the 1,200 new teachers each year end up in rural areas, such as in Leeward and Central Oahu and on Hawaii Island.

The problem is that it’s hard for teachers who are new to Hawaii to build a life there, Payne says: “If you don’t have family and you’re in a very transient group of people who don’t have roots either – like Lanai has a hard time hanging on to their teachers – it’s just very, very hard.”

Rick Paul, who just retired after serving as Hana High and Elementary School’s principal for 14 years, says his school has always struggled to retain and recruit teachers. The town of Hana is nestled on the east side of Maui and a two- to three- hour drive from the main city of Kahului. When the DOE recruits, he says, it goes to big cities like Portland and Los Angeles – and those aren’t places where suitable teachers for rural schools are found.

That means schools in rural areas have to be creative in how they recruit and retain teachers.

At one point, that meant taking a trip to South Dakota. Paul says he and a team from the “Canoe Complex” – made up of the Hana, Lahainaluna, Lanai and Molokai areas – did this for two years and targeted the state because it had high test scores, low teacher salaries and bad weather in the winter. The idea was that those teachers would be used to living in rural areas, they’d get a pay raise and they’d get to work in a warmer climate, he says.

In the years leading up to his retirement, however, most of his new teachers were starting out as substitutes or instructors at the school and enrolling in teacher preparation programs to become certified. Paul says that right before he retired, six or seven teachers were enrolled in such programs: “It’s kind of like on-the-job training, so we call it growing our own. And then that’s how I get my teachers.” Part of the problem with finding teachers for Hana, he says, is the lack of affordable long-term housing, so the school has been hiring more and more people from the community to be teachers.

For Naalehu Elementary, the challenge of retaining teachers also stems from the school’s remoteness. Naalehu Elementary is about 60 miles from both Kona and Hilo, and teachers commute from each side of the island, says Darlene Javar, who has been the school’s principal for eight years. Some of these commuters leave after three years – when their probationary periods are up – for jobs closer to home. Of her 30 teachers, anywhere from two to 11 are new each year, with larger numbers seen every third year. This trend has caused her to shift her focus from retention to training.

“My philosophy has been if you’re going to stay with me for three years, they have to be three good years, and so it’s how to train them fast and hard,” she says. “I stopped looking for retention at the school and I thought, ‘OK, if I’m going to train teachers, we’ll train them well and they will be good for the state of Hawaii.’ ”

Training begins before the school year with a 10-day new teacher academy. New teachers include those who are in their first or second year at the school and teachers who are switching grades. They learn about the DOE, the school’s academic plans and goals, and systems and curriculum used on campus. Follow-up training and mentoring are done throughout the year.

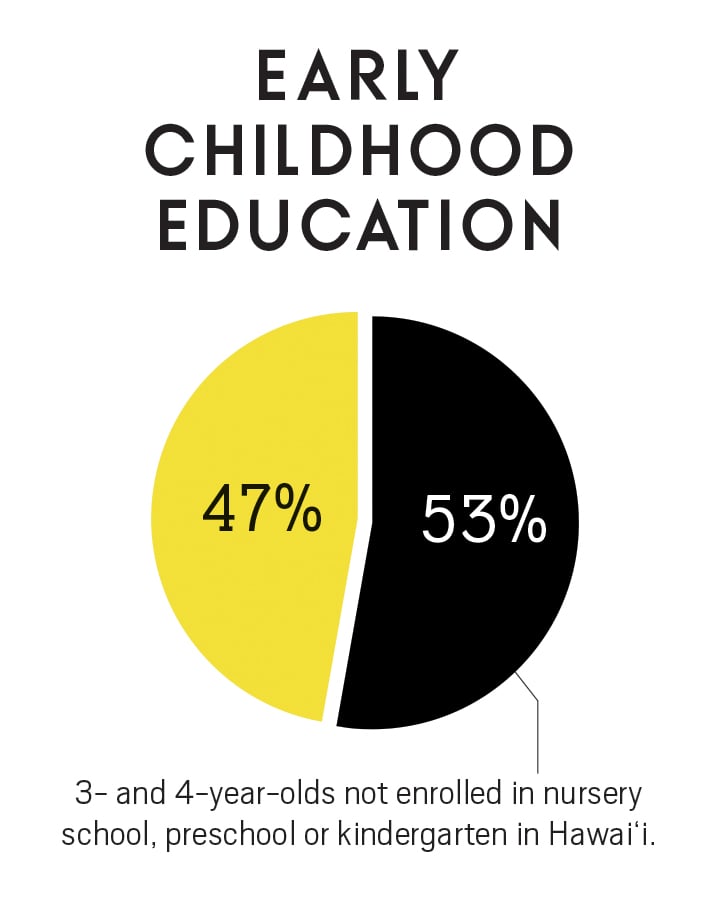

Javar says she’s not just trying to fill a space when hiring teachers. She needs the best for her students, who she describes as struggling learners. The school is located in a remote, high poverty area, where students have limited resources and transportation and often start school without the advantages conferred by preschool and kindergarten. In the 2017-18 school year, 28 percent of her students were English-language learners and 40 percent were chronically absent.

The DOE also provides a Beginning Teacher Summer Academy in 14 complex areas, and has a mentoring program. This year, about 650 mentors are advising 1,400 new teachers, according to the department.

Big Picture

Hawaii hasn’t always had a teacher shortage. When Payne and Joan Husted, a board member at the Education Institute of Hawaii and former HSTA executive director, began teaching in the 1960s and ’70s, it was hard to get a teaching job because it was a popular profession and for many people, a long-term career.

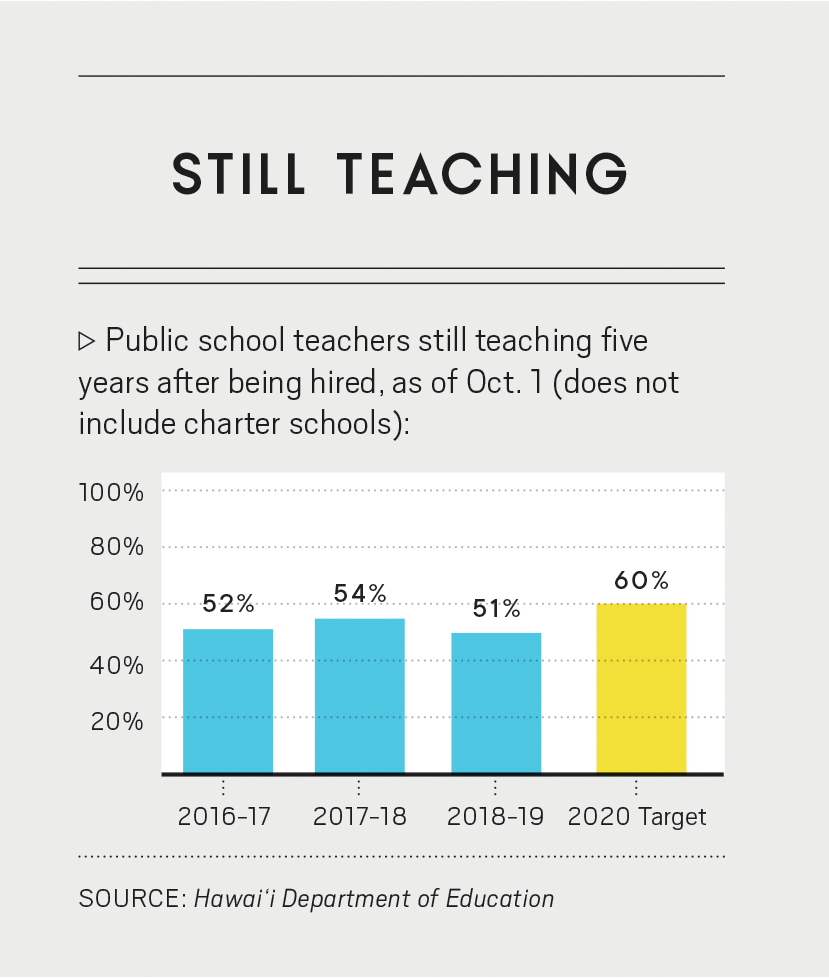

Then in the ’90s, a wave of teacher retirements and new career possibilities, especially for women, led to pockets of teacher shortages, such as in math and science. Today, the shortages have accelerated to the point where public schools are turning over 50 percent of their teachers in five years. The DOE’s goal is to retain 60 percent of its teachers for five years by 2020.

Then in the ’90s, a wave of teacher retirements and new career possibilities, especially for women, led to pockets of teacher shortages, such as in math and science. Today, the shortages have accelerated to the point where public schools are turning over 50 percent of their teachers in five years. The DOE’s goal is to retain 60 percent of its teachers for five years by 2020.

Husted says Hawaii won’t be able to progress in areas like student achievement, or move toward a school empowerment model, until it stabilizes its workforce.

“One of my frustrations is I don’t think enough people are talking about ending the teacher shortage,” she says. “They get so hung up with reforming the department and they don’t recognize if you don’t stabilize the people, you’re not going to reform the department.”

Lewis, who has been an educator since 1989, says the teacher shortage is a multifaceted and nuanced issue, so there needs to be a larger discussion about what Hawaii’s goals are for the teaching profession and public education and what it’s willing to do to improve them.

She says that involves everything from talking about teacher housing, how educator preparation programs need to prepare teachers for the 21st century, whether the state would be willing to pay more money to increase teacher pay and, with the growing number of Millennials in the workforce, whether Hawaii has to shift its mindset to thinking about teaching as a five-year career instead of a 30-year career.

“Until we’re going to sit down and have the real wraparound discussion – what do we expect, what do we want and what are we willing to commit to – everything we do is going to be a Band-Aid,” she says. “And then we’re going to wonder why we didn’t solve the problem.”

━━

Part 3b: New Way to Home Grow Teachers

For decades, the Waianae Coast has imported teachers who often ended up leaving after only a few years. Now, a pilot education program is turning motivated area residents into qualified teachers.

Hawaii’s teacher shortage requires thinking outside the box, especially when it comes to growing teachers on the Waianae Coast.

Leeward Community College and the Institute for Native Pacific Education and Culture are running a new pilot program that brings a teacher preparation program to Nanakuli. The pilot program targets educational assistants and paraprofessionals who live in the 96792 ZIP code – Nanakuli to Makaha – and want to become special education teachers, says Christina Keaulana, special education coordinator and instructor in LCC’s Teacher Education Program.

The Nanakuli pilot program is part of LCC’s 3+1 Bachelor’s of Science in Special Education program, which leads to licensure as a special education teacher. Classes are offered through LCC for the first three years, and the final year will be done online through Chaminade University, which will grant students their degrees. The pilot program began in fall 2018, and LCC anticipates that a cohort of about 16 candidates will complete their degrees, Keaulana says.

“Securing a nontransient, rooted teacher workforce is imperative to delivering quality educational services for a population who has consistently received the highest percentage of nonqualified educators in the state over the last several decades,” she says.

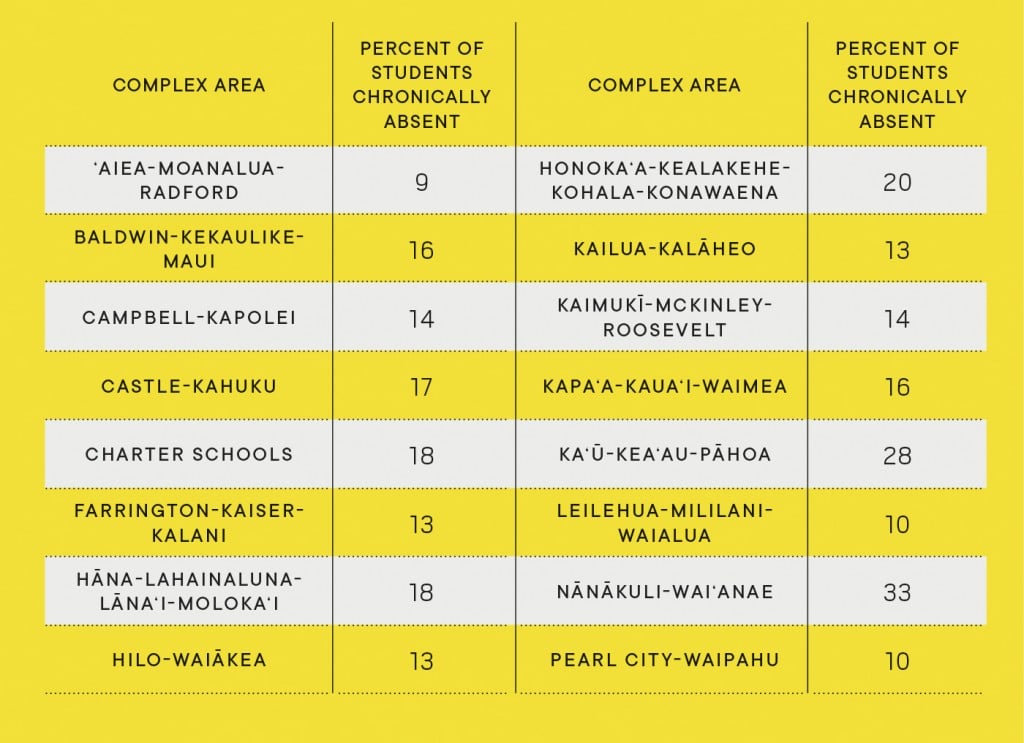

The Nanakuli-Waianae complex area is well-known for its high teacher turnover. Only 43 percent of teachers hired in the 2014-15 school year are still teaching in the complex area this school year, according to the state Department of Education’s Strategic Plan Dynamic Report. And teachers in this area are more likely to be unlicensed than in other complex areas. This school year, 16 percent of teacher positions in the Nanakuli-Waianae complex area are filled by teachers who are unlicensed and have not completed a state approved teacher preparation program. For special education teacher positions, that number is 29 percent. Both figures are far above the statewide average.

Untraditional Program

Bringing the program to participants on the coast removes many barriers that would typically prevent them from pursuing a teaching degree, like accessing classes they’d have to take in person and the rigid nature of traditional teacher preparation programs that require students to commit to taking a certain number of courses each semester, Keaulana says. The program’s hybrid classes are held during evenings, which allows most participants to continue working in their current jobs. Participants meet at Nanakuli Elementary School and at the Waianae Moku LCC campus, and classes are accelerated – it takes eight weeks to complete a course instead of the traditional 16 weeks during the fall and spring semesters.

Participants also attend a weekly study session facilitated by InPeace’s Kulia and Ka Lama Education Academy, which aims to help Native Hawaiians become teachers. The education academy provides wraparound services to help teacher candidates and current teachers succeed, including financial aid, textbook reimbursements, academic and career coaching, and connecting participants to support like housing and food.

Participants in the pilot program who work as educational assistants in the DOE can move up two pay steps as they complete parts of the program, says Cynthia Covell, assistant superintendent for the DOE’s Office of Talent Management. The progression through the two pay steps, which would classify them as teaching assistants, and associated pay increases reflect the additional responsibilities the participants undertake as they develop their teaching skills. She adds that if participants do not become certified teachers, they return to their educational assistant class of work and pay.

“They’re able to stay in their classrooms and work and continue to have health benefits, continue to support their families, and continue to serve the community they love,” Keaulana says. “They really like working with this population. Why should they have to resign from the position just to become teachers?”

Another benefit of the pilot program, she says, is that both class instructors and participants are familiar with the culture of Nanakuli’s students. Teacher preparation programs, she says, typically lack cultural training.

Teachers Needed

Special education teachers are needed across Hawaii but the greatest need tends to be in Leeward Oahu. The Leeward district – home to the Nanakuli-Waianae, Campbell-Kapolei and Pearl City-Waipahu complex areas – often has the most new teachers, many of whom are for special education. The DOE’s Employment Report for the 2017-18 school year says 327 newly hired teachers were placed in the Leeward district, and almost 35 percent were for special education.

Keaulana thinks the state has a shortage of special education teachers because of a misconception about special education students. She says people imagine either a medically fragile classroom with children who are nonverbal or have severe disabilities, or students who have behavioral issues and might bite or scream. “They don’t understand that there’s just this population of students who learn differently,” she says.

“We always call it like differently abled, not disabled,” she adds. “You find these amazing students who are just so unique that I think as a teacher you get to really showcase some of your best teaching … because it requires you to think, ‘How do I serve a student who has these, you know, sensory issues? How do I serve a student who sees words differently on a page?’ ”

She adds that special education has a reputation of being challenging and overwhelming for teachers. People tend to get nervous about the amount and importance of paperwork associated with the job, like individualized education programs, progress reports and data collection.

Sanoe Marfil, program director of InPeace’s education academy and Kupu Ola, the nonprofit’s culture-based education program, says children on the Waianae Coast aren’t encouraged to pursue a teaching career: “Our kids aren’t seeing folks who are super excited ‘Let’s be a teacher.’ ”

The DOE pays a $3,000 yearly differential to licensed teachers employed in hard-to-staff areas such as Nanakuli, Waianae, Kau, Molokai and Lanai, Covell says. But she’s heard that’s not enough to persuade teachers to stay in some areas where they must commute long distances.

Game-Changer

Diana Espanto, an educational assistant at Nanaikapono Elementary School, says the pilot program is a win-win for participating schools and educational assistants. She didn’t go to college and says she wouldn’t have pursued a teaching degree if it weren’t for the program.

“This is the best investment they can ever do because you’re helping people who are already in the school system, and they have on-the-job training. They live and work it. They know what to expect. But it’s just that piece of paper that’s holding them back,” she says.

Click here to learn more. | Source: Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center

Educational assistants at her school, she says, would make great teachers because they’ve worked there for years and understand what students’ needs are. She’s worked at the school in various positions since the 2004-05 school year and says she’s seen teachers – especially those who are fresh out of college or from the Mainland – quickly leave because they’re not ready to teach students like those in Nanakuli, who might come from broken families or be homeless.

Keaulana says other complex areas have expressed interest in replicating the Nanakuli pilot program. It’s a game-changer, says Darren Kamalu, assistant program director of InPeace’s education academy, because it opens the door to community members who wouldn’t normally be able to pursue teaching if they had to go through a standard teacher preparation program where lessons are held face-to-face on a university campus.

“This program provides the opportunity to think outside of the box and be very innovative when we’re trying to grow our teachers,” Marfil says. “And so more opportunities like this, more programs like this, would benefit.”

━━

Part 4: Designing Schools of the Future

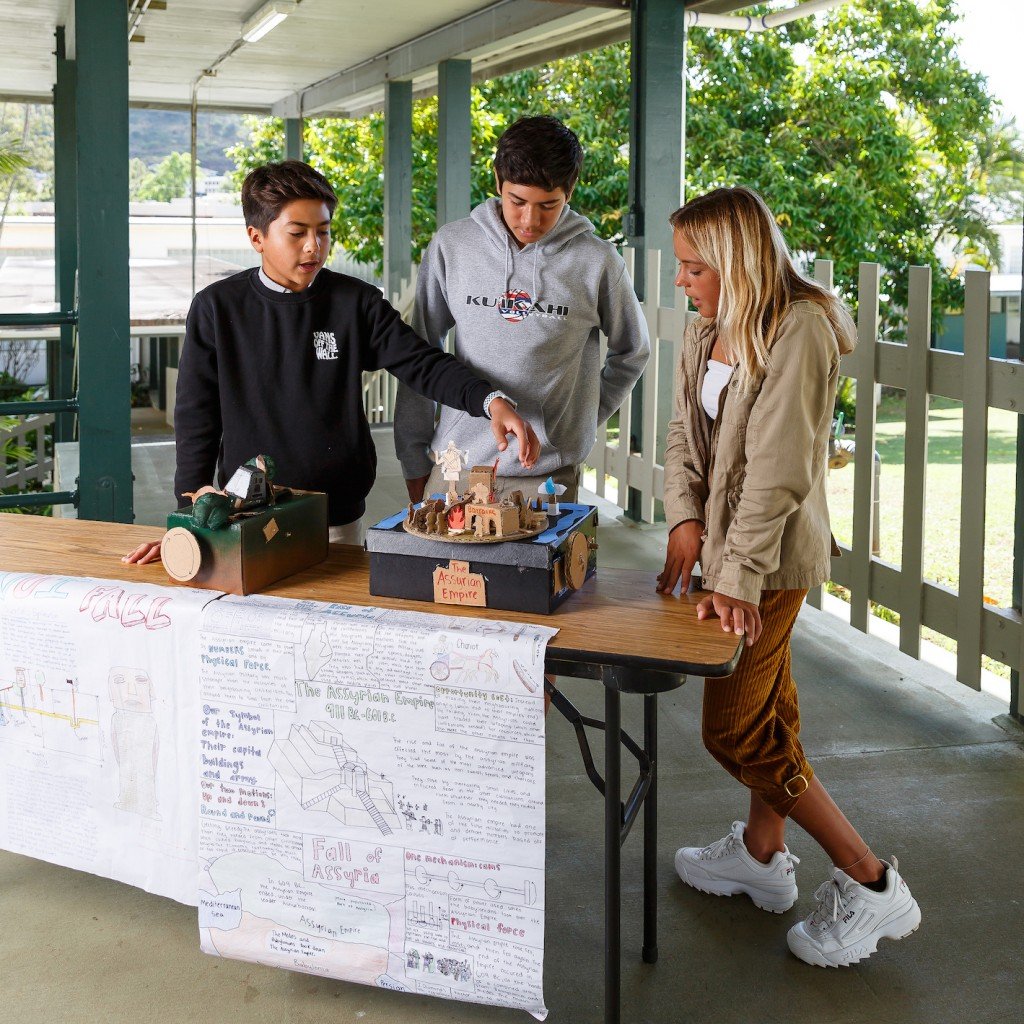

Students in Mid-Pacific Institute’s eXploratory Program are learning about ancient civilizations, levers, arms and machines.

Over four weeks, their task is to combine the knowledge and skills they’ve learned from their humanities and STEM classes to create physical structures that depict the rise and fall of different ancient civilizations.

The idea is that elements of the structures will move when a crank is turned, says Mark Hines, director of the Mid-Pacific eXploratory Program, also known as MPX. The inspiration for the assignment came from the opening credits of “Game of Thrones,” he adds.

Students from Mid-Pacific’s eXploratory Program Share their Automatons | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

MPX is an interdisciplinary program for 9th- and 10th-graders that teaches literature, history, science, technology and math curriculum through projects. The program launched in 2010 as Mid-Pacific and 17 other private schools were transforming their learning environments to better prepare students for the 21st century under Schools of the Future, a five-year initiative funded by a $5 million grant from Hawaii Community Foundation. The participating schools were encouraged to pursue education in which teachers became facilitators of knowledge – instead of lecturers – and students became active learners.

Today, many of the participating schools are role models for transforming learning and teaching, while 21st century learning is being discussed across Hawaii and the nation. Hines says Schools of the Future, which is also the name of the annual conference that resulted from the initiative, has helped to bring together the public, private and charter school community to address the role education must play in preparing keiki for the future.

By Design

Before the Schools of the Future initiative began, most of Hawaii’s private schools were stuck in the industrial-age model of being teacher- and content-focused, says Philip Bossert, executive director of the Hawaii Association of Independent Schools, adding that the exceptions were the Montessori and Waldorf schools, which focus on student-led, experiential learning. The independent school association ran the initiative with the Hawaii Community Foundation.

Conversations about 21st century learning were happening in pockets, says Piikea Miller, program director of strategies, initiatives and networks at the Hawaii Community Foundation; Schools of the Future made it a larger conversation.

From 2009 to 2014, Schools of the Future helped a cohort of private schools innovate their learning environments so that instruction would be student-centered and would help keiki develop skills in communication, collaboration, critical thinking and problem-solving. Each school set its own goals for how it wanted to accomplish this, and the initiative helped by funding professional development and technology integration, organizing a group tour to Mainland schools already using these learning environments, and hosting quarterly meetings where educators could share lessons learned.

Bossert adds that the initiative aimed to break down barriers that otherwise would have prevented the schools from changing their teaching practices. Most teachers, he says, were educated through the traditional teacher-focused, lecture-and-test model, so if they didn’t have time to invest in learning new strategies or couldn’t imagine how this new learning environment worked, they would continue teaching as they always had.

“The wonderful thing about Schools of the Future is it didn’t tell schools ‘Here is how you become a school of the future,’ ”

says Hines, who was part of the grant committee. “It was … a school identifying these are the things we know we need to work on, and then we were aggressive as a grant, as an initiative, to hold them accountable for those but also give them the opportunities to shape and adjust what that looked like so that it was right for them, their students, for where they were as a school and what their resources provided.”

Rethinking School

Fifteen years ago, teachers at Mid-Pacific primarily taught from textbooks, to a test and in isolation, says Hines, who has been with the school in various positions since 1985.

The MPX program came about, Hines says, after finding no examples of schools that were fully doing project-based learning. Mid-Pacific wanted to create a pilot program so the school could explore and understand the principles of project-based learning and deeper learning.

Today, some of these principles are part of the broader preschool to 12th grade campus. Teachers work collaboratively across disciplines, and instruction is rooted in projects and student-driven inquiry.

At Hongwanji Mission School in Nuuanu, David Randall, head of the school, says the initiative helped the campus, which serves about 350 students from preschool through eighth grade, create an environment where teachers feel safer trying new learning activities and teaching styles. Like at Mid-Pacific, much of the learning had been teacher-driven and occurred in silos before Schools of the Future.

Ninth graders from Mid-Pacific’s eXploratory Program learn about food sustainability and resource management. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

“From the time I got here, I said, ‘We want you to lead by example. We’re lifelong learners, we’re going to be trying new things throughout our lives and not everything is going to work,’ ” he says, adding that much of the culture change resulted from providing teachers with the time to collaborate and communicate about student expectations.

Yearly grants from Schools of the Future allowed the campus to restructure its daily schedule to include weekly meetings for teachers to meet with their grade clusters – such as preschool, K-2, 3-5, middle school – during the school day. Funds were also used for self-directed professional development activities and to upgrade the school’s IT network, which now supports 300 to 500 devices at a time.

It’s common for students to do hands-on activities like creating their own kapa using materials they grew on campus, building computers from scratch and learning about their family histories, Randall says, adding that he thinks Hongwanji Mission School maintains a good balance between student-centered and traditional teaching practices. While there are some hands-on activities, much of the preschool and elementary school curriculum still involves repetition, practice and support from teachers to set a foundation for students to jump into collaborative and project-based activities in the upper elementary and middle school levels.

Supportive Environment

The Schools of the Future initiative ended in 2014. An independent evaluation of the program by the American Institutes for Research found that the initiative helped teachers understand the importance of learning skills as an instructional goal, opened their eyes to more diverse teaching methods and changed their interactions with students. As a result, teachers saw higher student engagement.

One of the challenges, Bossert says, was that some teachers were against changes they saw as “destroying” K-12 education – such as replacing knowledge acquisition and standardized testing with “chaotic” student-led classrooms focused on developing skills and individualized learning. In addition, participating schools often accomplished pockets of change, but not widespread change.

The most important outcome, however, was the creation of a local community of educators focused on student-centered learning practices and technology integration that will support schools and teachers that want to change their learning environments, Bossert says.

Another outcome was the annual Schools of the Future conference, which launched in 2008 and is now co-sponsored by the Hawaii Association for Independent Schools, the Hawaii Community Foundation and the state Department of Education.

Miller of the Hawaii Community Foundation says the initiative did a good job launching the conversation about 21st century learning and then sustaining that conversation through the conference. Today, leading educators from public, charter and private schools agree they have to focus on designing learning experiences that allow students to accumulate knowledge and skills by doing relevant, authentic work, Hines adds.

One outcome at Mid-Pacific, he says, was the establishment of Kupu Hou Academy, which has provided summer workshops for teachers in project-based learning and other deeper learning practices. Since its establishment in 2010, he estimates, the academy has worked with 350 to 400 public, private and charter school teachers.

“I think most people have recognized this is not one of those moments of, ‘If I wait long enough, education will go back to the way it was,’ ”