Half of Hawaii Barely Gets By

Two or three jobs are not enough to provide financial stability for many local families. How can we create CHANGE?

━━

Table of Contents

Introduction

CHANGE Framework

Part 1: Hard Work is Not Enough

Part 2: Possible Solutions

Part 3: What Can I Do?

━━

by Steve Petranik

This report is about change – CHANGE in capital letters – because Hawaii cannot continue on its current path. We need to change.

We face many significant problems but the biggest may be that half of Hawaii’s people are struggling financially today despite a booming tourist economy and full employment. Even with frugal spending, they cannot save money for future financial needs regardless of whether they work two or three jobs. That struggle affects every aspect of their lives and their children’s lives.

Those families are the subject of this report: Who they are, how they barely get by and what we can do to help. There is no silver bullet, but there are key areas where changes can have a major effect.

This is the first of six reports from Hawaii Business Magazine based on a framework created by the Hawaii Community Foundation. “The CHANGE framework acknowledges the interconnected nature of community issues and zeroes in on six essential areas that constitute the overall well-being of these islands and people,” HCF says.

CHANGE stands for:

- Community & Economy

- Health & Wellness

- Arts & Culture

- Natural Environment

- Government & Civic Engagement

- Education

Hawaii Business will publish reports for the next six months on each of these topics. As HCF says, “By examining critical community indicators by sector, we can identify gaps where help is specifically needed and opportunities where help will do the most good.”

The six reports will not be comprehensive; that would take an encyclopedia. Instead we will focus on key elements and dive deep into specific subjects, with a focus on good ideas that might drive solutions. This first report focuses on the hundreds of thousands of working families and individuals in Hawaii who are living paycheck to paycheck, unable to thrive, barely able to survive financially.

Why is a business magazine doing these reports and why this business magazine?

A business magazine is doing these reports because businesses and business leaders must be part of the solutions. Government and nonprofits have not been able to solve these problems, so businesses must help.

This particular business magazine is stepping up because the owner and CEO of our parent company, aio, is Duane Kurisu. He is a successful businessman, but his roots are humble – he grew up in the plantation village of Hakalau and went to Hilo High School and UH. He knows what it is like to live like the struggling working families in this report.

He is the catalyst behind Kahauiki Village, the community for homeless families off Nimitz Highway near Keehi Lagoon Park. Homelessness is one of Hawaii’s seemingly impossible problems, but Kahauiki has made a big difference. Kurisu succeeded by bringing together business and nonprofit leaders, government, labor and many hundreds of individual volunteers.

His next step was to revive the annual Hawaii Executive Conference this past October as a way to bring together business leaders, nonprofit executives and senior politicians to focus on the major challenges facing our Islands. In between conferences, six CHANGE committees will focus on finding and implementing solutions to those challenges. This is not a single-year effort but a long-term commitment from many people.

This report and the five that will follow are part of that multifaceted approach. Positive change never happens unless people understand the challenges they face. Our reports intend to provide that intelligence. Full disclosure: We got support and input from Kurisu, the Hawaii Community Foundation and many other organizations and individuals, but no one outside the Hawaii Business editorial team had any control over the content of these reports.

We’d love to learn on social media about programs you recommend that are dealing with these problems. Please use the tag #ChangeHawaii on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram. Or tell us about issues we missed in our reporting and your overall thoughts on this CHANGE Report.

━━

Change Framework

Here is what the Hawaii Community Foundation says about the CHANGE framework: “Taking on the most pressing needs of our community relies on deep reserves of knowledge and the ability to bring people and resources together to find high-impact, long-term solutions.

“Leaders who step up to initiate change are well-suited to influence others to follow suit. When change advocates from across sectors choose to move forward collectively and commit to work in a results-focused, networked, and systems-oriented way, measurable progress can occur.

“The process begins with a personal commitment and expands to include allies whose missions align, as well as voices that currently go unheard. It is only by constructing effective coalitions between people and communities that we can create lasting change in and for Hawaii.”

Learn more here.

━━

Costs for Housing, Child Care, Food and Transportation

HOUSING COSTS

The National Low-Income Housing Coalition reports that Hawaii was the most expensive state for housing in 2015.

Least expensive county: Hawaii County, $1,151 on average per month for a two-bedroom apartment, $749 for a studio (also called an efficiency apartment).

Most expensive: Honolulu County, $1,810 on average per month for a two-bedroom apartment, $1,260 for a studio.

Mortgage foreclosure rate: 2.4 percent in Hawaii in 2015, third-highest in the country and double the national average of 1.2 percent.

CHILD CARE COSTS

Licensed and accredited child care centers, which are regulated by the state Department of Human Services to meet standards of quality care: $870 on average per month for an infant and $658 for a 4-year-old; total on average for children of this age is $1,528. The household survival budget includes the cost of registered home-based child care at an average rate of $1,207 per month ($610 per month for an infant and $597 for a 4-year-old). Sources: Hawaii’s Child Care Resource and Referral Agency, 2017; Hawaii Department of Human Services, 2015; Hawaii Department of Human Services, 2017.

FOOD COSTS

The cost of food increased in Hawaii by 35 percent from 2007 to 2015, more than double the overall rate of inflation.

Within the household survival budget, the cost of food in Hawaii is $1,032 per month for a family of two adults and two young children and $312 per month for a single adult, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2015.

Food accounts for only 17 percent of the household survival budget for a family and 13 percent for a single adult in Hawaii.

TRANSPORTATION COSTS

A Hawaii family pays an average of $544 per month for gasoline and other vehicle expenses.

Average cost for public transportation is $64 per month, but comprehensive public transportation is available only in Honolulu County. Across all Hawaii counties, fewer than 8 percent of workers use public transportation, so most workers must have a car to get to work.

Transportation costs represent 9 percent of the average household survival budget for a family and 12 percent for a single adult.

From 1999 to 2012, the auto debt per capita in Hawaii increased by 73 percent to $2,510, according to a national report by Stacy Jones at Bankrate.com.

━━

Part 1: Hard Work is Not Enough

Half of Hawaii’s people are struggling financially

even while many work two and three jobs

by LiAnne Yu

Lanae Anakalea, her husband and their two young daughters are not what most people would envision as a family in economic distress.

Both parents are fully employed. He’s a valet at a major hotel on Kauai, with full health benefits and a 401(k). She works at a foundation promoting Native Hawaiian culture. Their combined yearly take home pay of $60,000 is in line with what the U.S. Census Bureau says is an average U.S. household income, and over twice the federal poverty level.

But look closer and the picture gets complicated. Rent is their biggest cost: Even though their current home is just a “laughable jungle home,” as Anakalea puts it, they cannot find anything cheaper for their family of four. To cover the monthly rent of $2,350 plus $600 for utilities, they sublet one room.

Two full-time jobs are not enough. She waits tables on the weekend and picks up catering gigs whenever she can. Even with the extra income, they can’t afford child care or the $300 a year to put both daughters on the school bus, so they spend hours every week shuttling their kids back and forth to school, and she brings them to work with her after school.

Despite being frugal, they have nothing left at the end of the month. Anything beyond basic survival expenses means a difficult trade-off. “When my kids want something, I say that means we have to be separated more so I can work.”

The Anakalea Family | Photo: Mallory Roe

Anakalea and her family aren’t unique in their community. All of the people around her work multiple jobs and still struggle to get by. “Everyone here is surviving. But we don’t want to just survive, we want to thrive,” she says.

“To thrive is to not have to choose between putting gas in the car or buying groceries for the kids. It’s to be able to say it’s Christmas and I want to buy my kids these toys and not have to stress over that. To thrive is to live and move forward without picking and choosing.

“That’s not to say you can’t be frugal and thrive. But for me, thriving is feeling safe and secure and not having to stress about survival.”

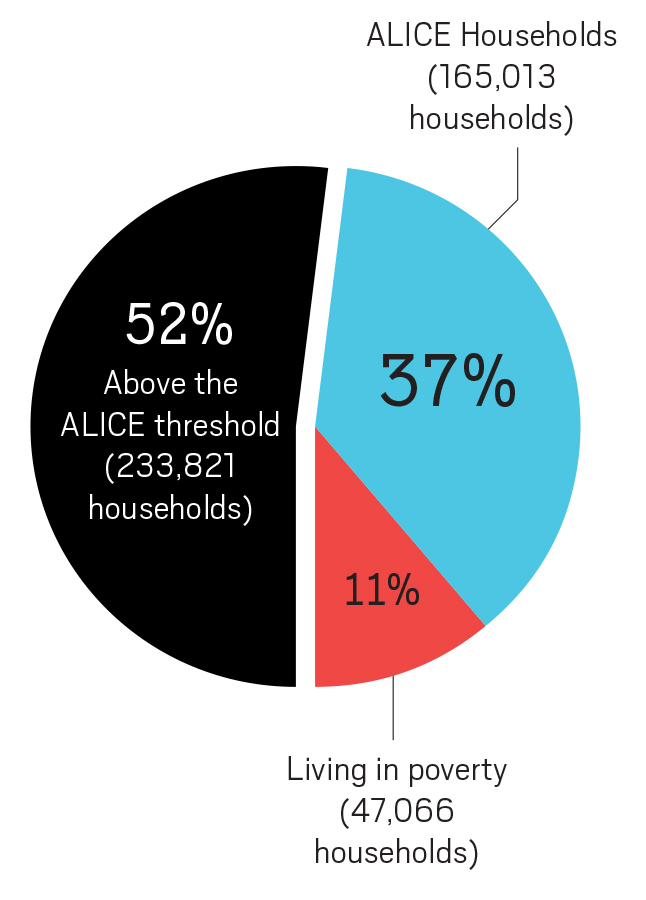

Many numbers suggest that most people in Hawaii should be thriving. Only 11 percent of the population lives in poverty according to federal standards, one of the lowest rates in the nation. The unemployment rate is a historically low 2 percent, the visitor economy keeps growing and Hawai‘i’s median household income is relatively high compared to the rest of the country.

Yet so many of us can name friends, colleagues and relatives who, like Anakalea’s family, are just a paycheck or emergency away from losing their homes.

The Aloha United Way wanted to better understand the challenges of people who are hardworking yet financially vulnerable. So the nonprofit commissioned a report called “ALICE: A study of financial hardship in Hawaii.” The acronym describes working individuals and households living on the financial edge.

- AL for Asset Limited: little or no savings and owned property to fall back on during times of sickness, job loss or other financial crisis.

- IC for Income Constrained: not earning enough money to create a savings cushion to weather those crises.

- E for Employed: working and still not getting ahead even in a strong local economy.

The ALICE report defines a household survival budget specific to Hawaii. This includes the bare minimum amount of after-tax income needed to cover the fundamentals of housing, transportation, child care and food. For a single adult under 65, it’s $28,128, and for a family of four, like Anakalea’s, it’s $72,336. These figures are much higher than the federal poverty level, which accounts for some increases in the cost of living over the years, but is based on a formula that has remained largely unchanged since 1965.

In Hawaii, 11 percent of the population falls below the federal poverty level. An additional 37 percent don’t make enough to meet the basic survival budget, according to the ALICE report. Combined, 48 percent of the state is financially vulnerable – either in deep poverty, or on the precipice of it. People like Anakalea and her family and most of the people she knows. And they are spread across all the islands.

In other words, almost half of Hawaii’s residents are, as Anakalea puts it, focused solely on surviving rather than thriving.

“Those in the social services space and the nonprofit space where we serve and are involved in helping human services, were not surprised by the high number of ALICE households in our state. Nonetheless, it’s good data to have because we now have a reference point, a benchmark to measure against,” says Cindy Adams, president and CEO of Aloha United Way.

For Joyce Lee-Ibarra, who was on the ALICE Research Advisory Committee for Hawaii, recognizing ALICE households as a large segment of the population also helps us come to grips with the reality of financial hardship all around us. “People tend to compartmentalize the homeless – they are seen as ‘the other.’ But in reality, so many of us know so many people who are just a health crisis or major car repair away from catastrophe. This report helps us understand that we in fact sit on a continuum and our experiences are not that far separated,” says Lee-Ibarra, the president and CEO of JLI Consulting.

The ALICE findings have, for many of the state’s business leaders, made it clear that despite how well we compare numerically to the rest of the U.S., our communities are not as healthy as they may appear from just a numbers standpoint.

“It’s important for our business community and policymakers to recognize that if we continue to have this condition, this extreme lack of affordability for such a large portion of us, this will become something of an economic crisis in and of itself,” says Peter Ho, chairman, president and CEO of Bank of Hawaii. “The people who can’t afford to live here will simply leave the Islands. So what we’re on the forefront of is an exodus of an important part of our community, both from a social standpoint and an economic one.

“That potential outcome should alarm everyone. That situation left unchecked for an extended period of time threatens the economic underpinnings of our fragile economy,” Ho adds.

In this next section, we put names, faces and real-life stories on the statistics to understand the personal struggles and aspirations of the local people we call ALICE. Who are they and what shapes their choices?

One Job is Not Enough

Lourdes Maquera’s day begins at 5 a.m., when she starts getting her 13-year-old son ready for school. At 6, the single mother of three is on her way from her Waipahu home to Waikiki for her job as a hotel housekeeper. Just before 2 p.m., she rushes to change and get to her second housekeeping job. Her knees are so worn from the work that she can barely get out of her car when she gets home by 11 p.m. But she still has to do her own housework, prepare meals for the next day and check in on her son’s homework.

Her annual take home pay of about $40,000 is only about half of the household survival budget for a family of four. Despite two jobs, she is barely able to cover everything: rent, utilities, food and car payments, and her two daughters’ college loans. Most months, she has to rack up more credit card debt.

“When we came to America from the Philippines, we knew it would be difficult. But we thought that the promise of life here is that so long as you work hard, you’ll earn enough and not be drained. But it’s not like that at all,” she says.

To save money, she moved her family of four from a three-bedroom place that cost $1,700 a month to a two bedroom for $1,375. Even at this lower price, her rent eats up 40 percent of her take-home pay. According to federal guidelines, families that pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing are considered cost burdened and may have difficulty affording other necessities. Maquera is far from alone: 47 percent of Hawaii’s residents spend more than a third of their monthly income on housing

There is almost nothing she can do to reduce her rent even more. The average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Hawaii is $1,362 per month, according to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. But on Oahu the average rent for a two-bedroom in November 2018 was $1,800, according to Rent Jungle, an online search engine that tracks rental housing in cities nationwide. That makes Maquera’s Waipahu place a relative bargain.

“In 1968, 23 percent of Honolulu renters were paying more than 30 percent of income for rent. By 2005, 46 percent of Honolulu renters. By 2016, 54 percent of Honolulu renters.” – Gavin Thornton, Co-executive director, Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice

Gavin Thornton, co-executive director of the Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice, has been looking at housing studies dating back to 1946. He found one from 1970 describing Hawaii’s housing problem. “That study from 48 years ago was already saying we were in a crisis. And what has changed since then? In 1968, 23 percent of Honolulu renters were paying more than 30 percent of income for rent. By 2005, 46 percent of Honolulu renters. By 2016, 54 percent of Honolulu renters.

“So we were calling it a crisis back in 1970. And yet the problem is twice as big now,” adds Thornton, who was on the ALICE committee.

The high cost of living is also driven by the state’s reliance on imported oil for electricity generation and transportation. The average retail price of electricity in Hawaii is 33 percent higher than in the second-most expensive state, Alaska, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

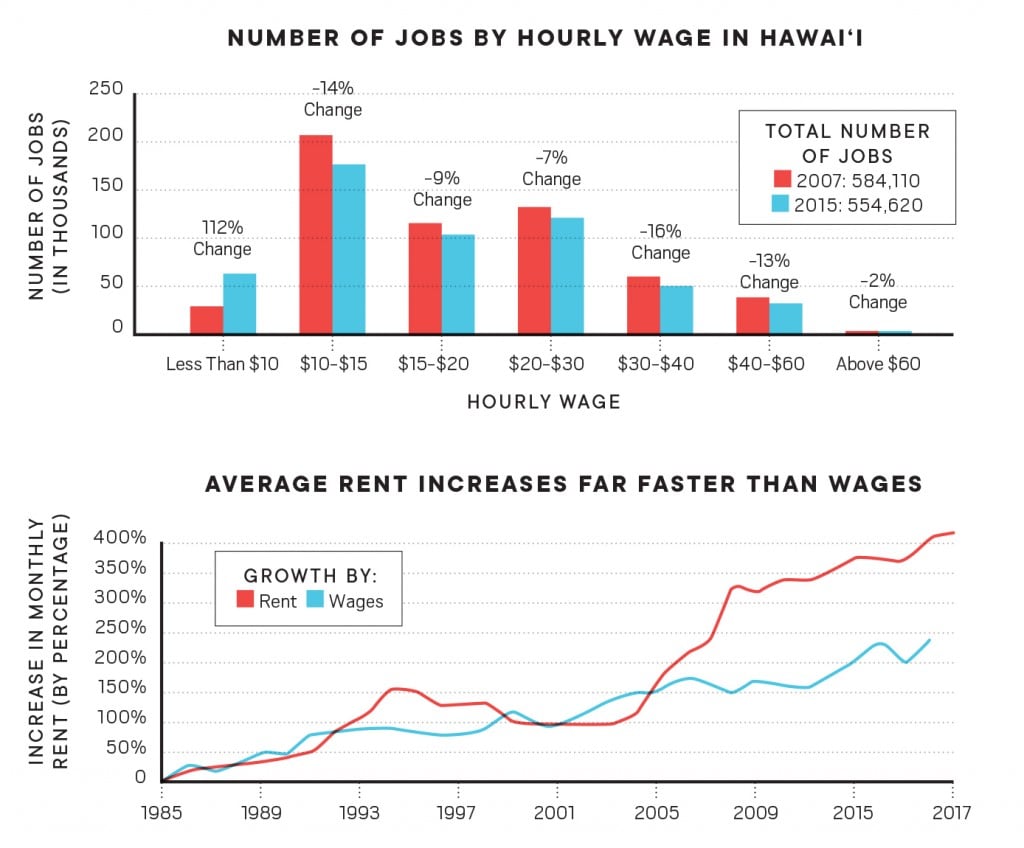

Workers like Maquera face not only high housing and electricity costs but low wages, relative to cost of living. About 62 percent of the jobs in the state pay less than $20 per hour. Of that portion, two-thirds pay less than $15 per hour. According to the ALICE study, a parent supporting a family of four working 40 hours a week would need to make at least $36 an hour just to reach the threshold of the survival budget, but when I first spoke with Maquera, she was only making $22.14 an hour at her primary job.

The state’s reliance on the general excise tax for its revenue also makes necessities for ordinary people more expensive. That’s because the tax is applied at each step as products make their way to the consumer: from an item coming into the harbors, through the wholesaler and over to the retailer. That raises the price of everything, from toilet paper and diapers to milk and rice.

“The lowest-income folks in Hawaii are paying 11 percent of their income in just GET. That’s a lot of money. Yes, we have to raise wages, and we have to work on affordable housing. But we also need to look at the tax burden,” says Nicole Woo, senior policy analyst at Appleseed.

Maquera says, however, her most challenging burden is the emotional one. “My son is growing up and wants his own room. I keep telling him, just be patient. Just help me save money for now, so one day we can get our own house. I’m so lucky because he is bright, he understands a lot. But I can’t make it to any PTA meetings. I can’t hear the teacher announce how well he’s doing. Then he says, ‘Mom it’s not fair. Why do other moms get to spend time with their kids, and why can’t you?’ This tears my heart apart.”

The High Cost of Being Poor

Nicole Schubert has been making regular payments of $380 a month toward her student loan. The Kalihi public school teacher, who has both an MBA and a master’s degree in teaching, is paying as much as she can toward her debt, but it just hasn’t been enough.

“My total payments since 2013 have been more than $12,000, but the principal balance has only been paid down $12. All of my payments go towards interest, so my student loan balance continues to rise every year and is now over $145,000,” says Schubert.

The recently divorced 39-year-old describes herself as a hustler, supplementing her teacher’s salary with side gigs, including managing an AirBnB, remodeling and painting homes, and selling things on eBay. Among the teachers she knows, she is not unique.

“Everyone I work with does something on the side because everyone here is so vastly underpaid but still has to pay $2,200 for a two-bedroom. I know teachers who are part-time financial planners, Uber drivers and bartenders. The only people I know who don’t have second and third jobs are teachers who have a spouse who makes a lot of money,” she says.

“My friends and I talk about our hustle all the time. It’s just part of our livelihood. I don’t even think about how much I’m doing, I’m just doing it every day. It becomes part of your life. Your free time is working. At the end of the day, you’re exhausted,” Schubert adds.

Nicole Schubert in her classroom | Photo: Elyse Butler

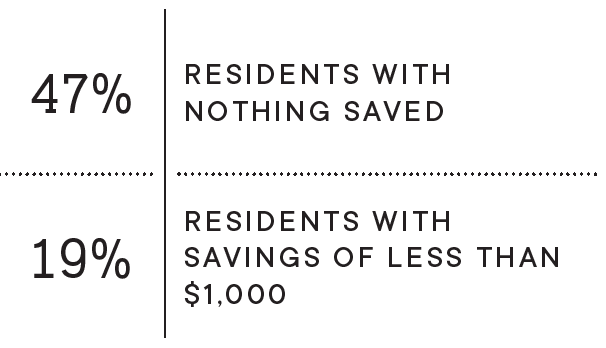

ALICE households typically don’t have anything at the end of the month, so they cannot build savings, accumulate assets or protect themselves from emergencies such as a car repair bill or medical costs.

“They put it on credit cards and it becomes a vicious cycle. The interest continues to grow; it comes back around full circle in that they can’t start saving or putting away for a rainy day,” says Lee-Ibarra of JLI Consulting.

In “The High Cost of Being Poor,” an essay funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the authors describe how the poor end up paying far too much for basic necessities. For example, owning a car is critical for lower-wage workers who work odd hours or live far from public transportation. But if the person has poor credit or no credit history, that can mean incurring excessive fees and interest rates. According to the ALICE report, people with only fair credit may spend six times more to finance a vehicle than those with excellent credit.

Jamie Borromeo Akau, a Hawaii Island schoolteacher who also has nothing left at the end of the month, saw her car payments go up due to some late payments. “I just trusted that my husband was sending in the check or paying it automatically. When we went to trade in the car for a new one, they told us that our credit score was lower because my husband was making the car payments late. I was only paying 2 percent interest. Now it’s like at 6 or 7 percent.”

Low-income consumers often have less access to mainstream banks, and end up turning to subprime or predatory outlets such as check-cashing and payday lending places.

“A lot of families we serve fall into getting scammed,” says Samantha Church, executive director at Family Promise Hawaii, a nonprofit that helps homeless families transition into permanent housing. “They go to payday advance places, or a lot of them get a car with a loan that’s an insanely high rate. It’s their first time learning about credit and interest rates and basic financial literacy. We have families who don’t know what a credit score is. They don’t realize what affects it and impacts it. It’s a life skill that so few people know.”

Among her schoolteacher friends, Schubert says, she’s not the only one mired in debt. “My first year here, I knew a teacher whose student loan payment was so high, he lived in his truck and showered at school. This is the plight of our generation – you have to go college, and now we are all broke.”

━━

Thriving or Struggling in Hawaii?

━━

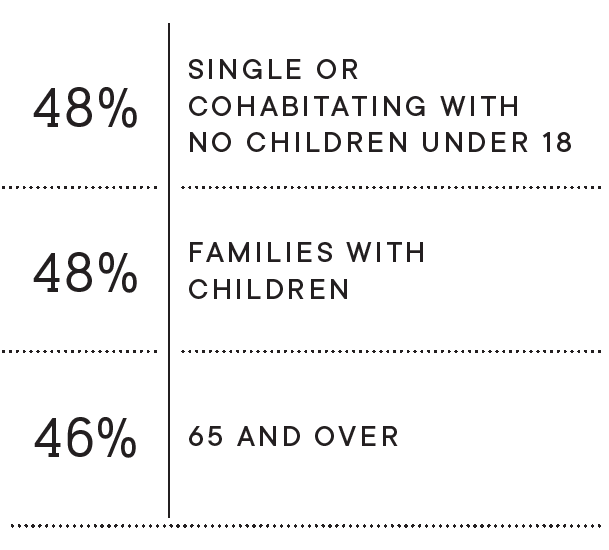

Percentage of each group that is

either in poverty or ALICE:

━━

Little or no Savings

Hawaii is the state where you’re most likely to live paycheck to paycheck, according to the latest annual survey by gobankingrates.com.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, 2015, and the ALICE threshold, 2015

━━

Loved Ones Suffer the Trade-Offs

Akau, the Hawaii Island teacher, and her husband, Charles, have discovered the joy they expected in having a child. But they have also discovered new financial obligations they can barely cover with their combined take home pay of $4,000 a month.

“When Eva came it threw our budget completely out of whack. Diapers. Oh, my God. Her diapers were $45 for a box that lasts us about two weeks, so $90 a month. Baby wipes is probably another $50 a month. Formula’s about $35 a week.

“There’s no savings. There can’t be. My mom’s a big stickler. She’s like, ‘Put 10 percent away.’ I’m like, ‘Mom, you don’t get it. There is no 10 percent,’ ” says Akau.

To make ends meet, they sublet two rooms and AirBnB a third room in the Hawaii Island house that actually belongs to her mother, leaving the young couple and their baby just one room upstairs in a house that feels more like a hotel than a home.

“I can’t even come out in my pajamas downstairs because I’ve got customers there. I literally just stay in my room. I close the door when I come home from work and I don’t open it because this is not my house. This is my place of business. I don’t even sit on the couches. We have no privacy at all,” she says.

The new parents barely see each other. As a schoolteacher, Akau works in the day while her husband works in the evening. They take turns watching their 1-year-old, but there’s an overlap in their work schedules, during which they need help with the baby.

The Akau Borromeo family | Photo: Dino Morrow

“The one expense that we cannot handle is day care. You’re talking 15 to 20 bucks an hour. That’s how much Charles makes. So we use this unlicensed baby sitter. It’s $5 an hour. Her sister’s up the street and baby-sits eight to 10 other kids. It’s just a local network of unlicensed baby sitters,” Akau says.

She emphasizes that the woman running the place is a trustworthy auntie, but at the same time, the conditions aren’t ideal. “It’s small, it’s tiny, there’s one little playpen and all the older kids napping. Just lined up bodies.”

The average cost to put an infant in a licensed and accredited child care center is $870 a month; it’s $658 a month for a 4-year old. Even if they could afford the care, the Akaus have few choices as the Neighbor Islands are considered child care deserts.

“Families are piecemealing things together, relying on friends and neighbors to watch kids, and sadly, we’ve had a lot of children in substandard care that’s not regulated,” says Deborah Zysman, executive director of Hawaii Children’s Action Network.

And standard child care doesn’t accommodate the working hours of most ALICE parents. “Only about 2 percent of our child care seats in the state offer any evening or weekend hours. Those most likely to have those kind of jobs tend to be your low-income workers who are doing fast-food, restaurant and janitorial work,” says Barbara DeBaryshe, interim director at the UH Center on the Family.

Even though Akau loves teaching in her community and wants her daughter to grow up surrounded by her Native Hawaiian heritage, the trade-offs they are forced to make may be too much for her. She and her husband are seriously considering moving to California, where her mother could help with child care. “This is not normal. People in and out of your home is not normal. A husband working six days a week is not normal. Not ever seeing your spouse because you have to flip schedules is not normal. Not being able to afford child care, cost of food, cost of gas, is just not normal.”

Putting My Well-Being Last

Andre Holcom regrets not having enough time for everything that’s important to him. He and his wife work two jobs each to support their three children. On weekdays, he’s a server at a major hotel on Maui. On weekends, he works the lū‘au at another hotel. His wife works as a waitress and then takes the graveyard shift at the supermarket. They barely see each other, and he describes their relationship as “two ships passing each other in the night.”

“We rarely do stuff all together as a family – that’s hard when you juggle a schedule. It’s emotional, and kids start off as little kids and suddenly they are adults and you feel like you’ve missed their childhood because you’ve worked their whole life,” Holcom says.

But he doesn’t see any way out of this. “If one of us couldn’t work, we wouldn’t be able to pay our bills. We would probably have enough for one month. But that’s pushing it,” he says.

His wife and kids aren’t the only ones he’s not seeing enough of. He’s also not visiting a doctor regularly to manage his diabetes, even though he has health care coverage.

“I just don’t have time for the doctor. You have to take time off work to go. I’d only go if I were so sick I couldn’t go to work. And anyway, they’re just going to tell me to take medicine and eat this or not eat that,” he says.

Maquera, the housekeeper who works seven days a week at two different hotels, struggles with pain in her knees and back. Even though she has insurance, she hasn’t seen a doctor because that would mean taking time off work. She fears that any missed days on her record would endanger her job.

“I just don’t have time for the doctor. You have to take time off work to go. I’d only go if I were so sick I couldn’t go to work.” – Andre Holcom, He and his wife both work two jobs on Maui

“You don’t go to the doctor unless you can’t get up from bed. Even though you have pain from last night, just take a pain reliever, or put pain oil on it and get to work. Even if we don’t feel good, we have to go,” Maquera says.

ALICE households often make trade-offs on health care. “A family may have expensive medication as a household cost. But paying for that medication as it’s prescribed might mean they have less money for groceries, or come up short in rent. Maybe they will fill their prescription half as often, or split up medications so they are only taking half of the prescribed dosage. People are trying to figure out how to be creative given the means that they have,” says Lee-Ibarra of JLI Consulting.

Low-wage workers, who frequently deal with physical stress on the job, must also deal with the mental stress from financial hardship. “You have so much on your mind to think about every day. How am I going to get through this, how am I going to survive, are we going to be able to have enough for this month, can I pay the bills? With all this, there’s not a time when your mind is at rest,” says Faye Cholymay, a mother of three who works in catering for a major airline and takes home $1,400 a month.

Lee-Ibarra describes the impact of financial distress on their decision-making. “There are the manifestations of that type of stress in terms of physical and mental health. But I think more deeply than that, it has an impact on the kind of time-horizon people are able to make decisions on. If you are constantly in a situation of worrying what fire you might have to put out or fending off emergencies, then your thinking and decision-making tends to be very present focused. That present bias means personal health may get pushed to the wayside.”

━━

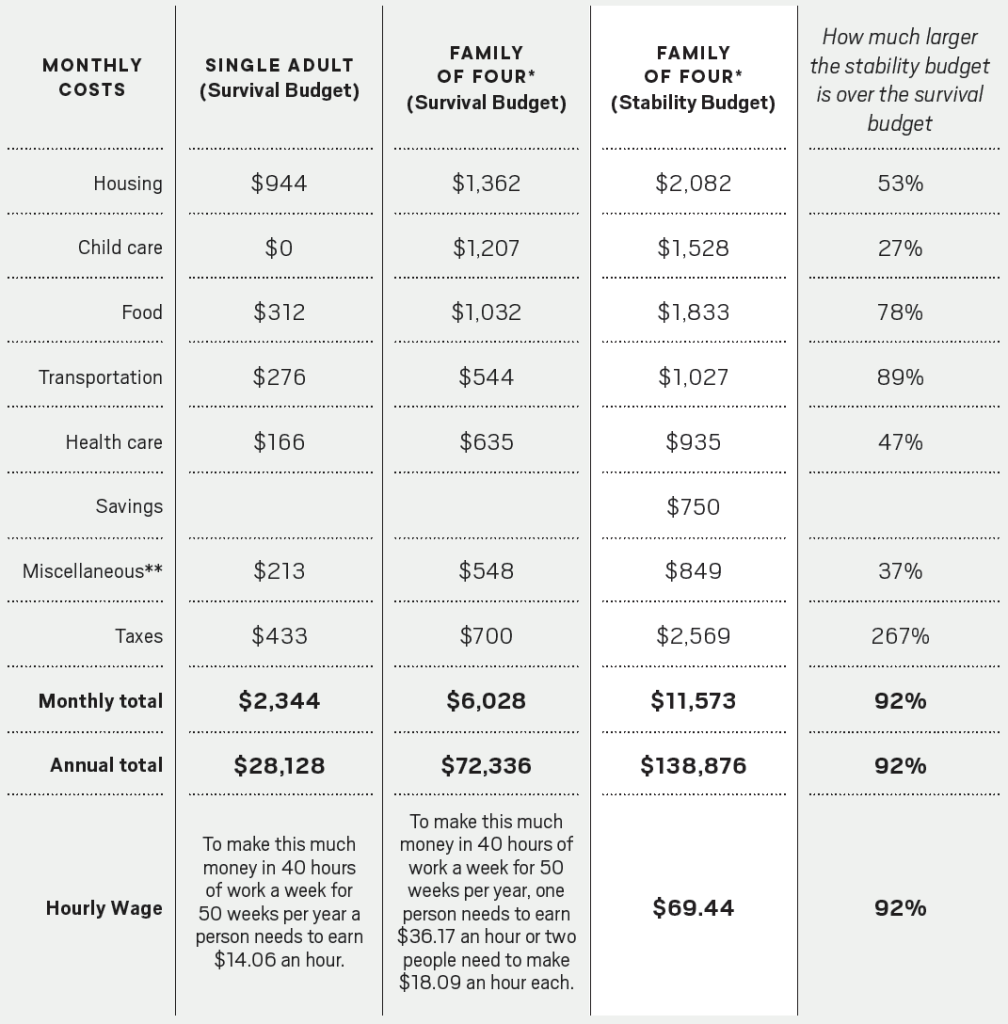

Can You Survive on This?

Here are two household survival budgets from the Hawaii ALICE report. These budgets include nothing for entertainment, auto repairs, restaurant meals, children’s birthday or Christmas presents, new appliances or emergency costs.

The household stability budget is a measure of how much income is needed to support and sustain an economically viable household. The stability budget represents the basic expenses necessary for a household to participate in the modern economy in a sustainable manner over time. Here are figures for the stability budget for a family of four.

*2 adults, 1 infant, 1 preschooler; ** Miscellaneous includes toiletries, diapers, cleaning supplies, work clothes and smartphone.

ALICE report sources: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015; U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015; Internal Revenue Service, 2015; Tax Foundation of Hawaii, 2015, and Hawaii Department of Taxation, 2015; and Hawaii Department of Human Services, 2015. For full methodology, see methodology overview at unitedwayalice.org/hawaii.

━━

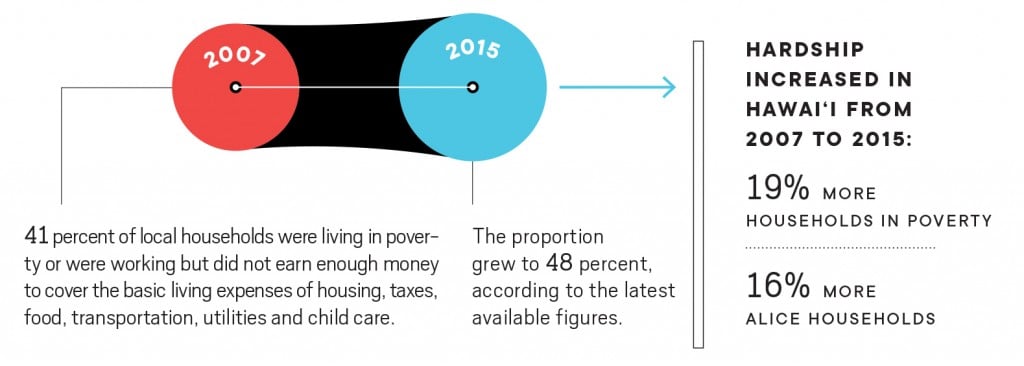

Getting Worse

More and more Hawaii families have gone from financial stability to instability in the past decade.

━━

Navigating a Complex System

Retired Navy veteran Carl Stork, 70, says food stamps have made the difference between making ends meet and going homeless. The bulk of his $1,400 Social Security check goes toward his 200-square-foot Kalihi studio, which is a bargain at $735. But outstanding medical bills for a bad shoulder leave him broke every month, while his credit card bills remain unpaid.

Food stamps (now officially known as SNAP) cover a few trips to Costco every month, where he stocks up on low-cost items like rice and Spam. But getting the food stamps is, he says, just good luck. A random person mentioned that he should find out about qualifying, which had never occurred to him before.

“The biggest challenge for people like me is knowing what you qualify for. The only people who have any counselors are the homeless. But people like me, who are retired, have to poke around. The state doesn’t come out and ask you if Social Security is your only form of income. They don’t care. The places that do offer the benefits, they don’t have any outreach. There was nobody checking in on me, asking, are you making enough?” Stork says.

Even if a person finds out about the benefits, there are other challenges. “Some of these applications are very long and arduous for just a small amount of support,” says Brent Kakesako, executive director of the Hawai‘i Alliance for Community Based Economic Development.

“For example, for SNAP you’re required to do a six-month review, and if you’re houseless, you may not have a permanent address. And it may be hard to get ahold of you by phone. If you don’t respond you automatically lose your benefits. If you try to reapply you have to start from scratch. It’s a disincentive for people to improve their situation.”

Kakesako adds: “Others may argue that we’re just trying to hold people accountable, but statistically, fraud is extremely low. And most people try to use the benefits the way they are supposed to. They aren’t trying to game the system.”

The ALICE report also states that many needy families choose not to apply for help because of all of the costs incurred in the application process. It involves time off work, child care, transportation and potentially lost wages.

“For people who need timely access to critical benefits, interacting with the government can become as time consuming as a part-time job,” write Jess Kahn and Mollie Ruskin in an article for the U.S. Digital Service, a federal agency set up to “deliver better government services to the American people through technology and design.”

There is also a matter of trust, Kakesako says: “Applications ask for lots of sensitive information such as Social Security numbers, birth certificates. An application process also asks a lot of questions, sometimes very personal ones. That creates a hesitancy to engage and a defensiveness. It’s not clearly communicated why an institution needs to know all of this, and unclear what part is federally required, what is state, and what is obsolete.”

━━

In most cases, the biggest burden for ALICE families is housing.

That’s not surprising: Hawaii has the nation’s costliest housing. There isn’t enough affordable housing, and Hawaii Business has reported repeatedly on the many reasons why: The cost of land and construction is usually high compared to most of the rest of the country; the permitting process can be arduous; building affordable housing often requires free land and other subsidies to pencil out.

According to a report put out by the Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism, an additional 64,700 to 66,000 housing units will be needed by 2025 in Hawaii to meet demand. But in a similar period of time, 2008 to 2015, available housing in Hawaii, regardless of price level, increased by only 14,448 units, according to federal Census Bureau statistics.

To address the crisis, Gov. David Ige signed a housing measure in June injecting more than $200 million into state funds aimed at increasing the production of affordable rental units across the state. In November 2018, the Honolulu City Council passed a bill requiring building permits for one- and two-family homes to be issued within 60 days after applications were submitted. Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell allowed the bill to become law without his signature.

━━

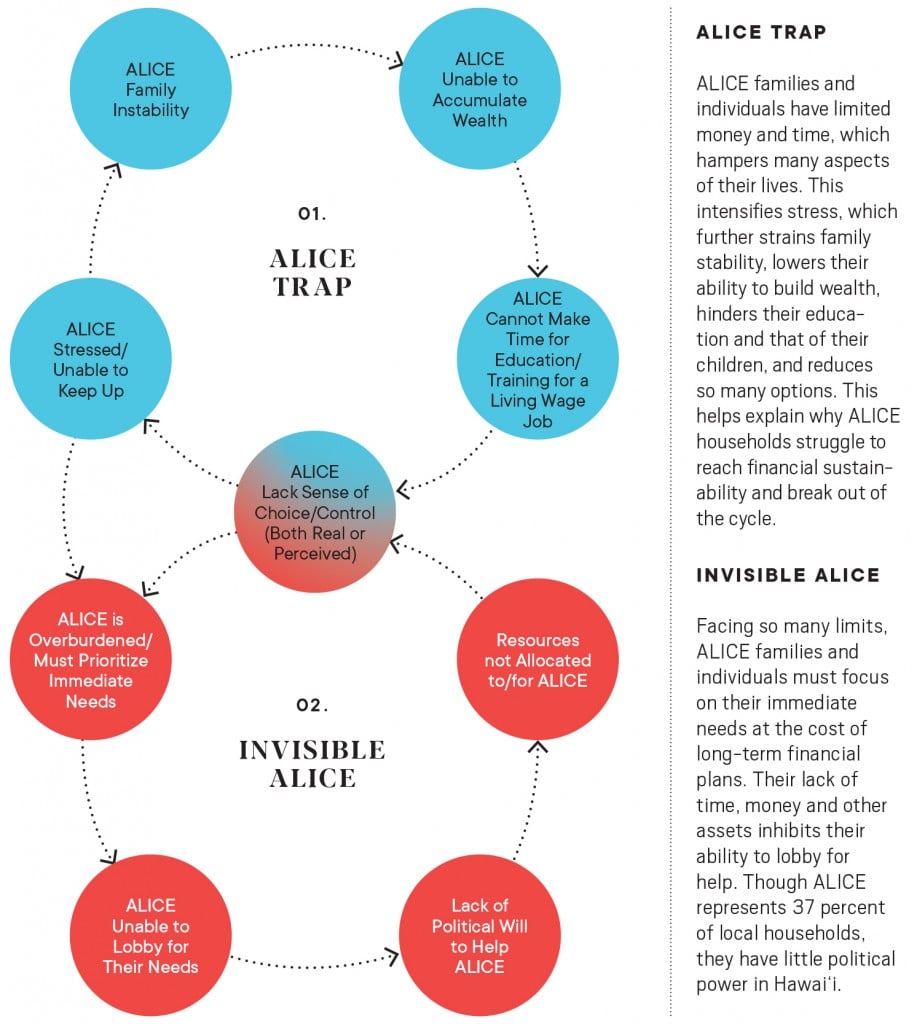

A Holistic Way to Understand

The image below shows a few loops from a more detailed systems map of the challenges faced by ALICE households.

A systems map is a visual representation of how cause-and-effect relationships perpetuate or worsen aspects of our society. These cause-and-effect relationships often form “loops” that feed themselves – which can help explain why some social problems get worse despite efforts to reduce them.

The full Hawaii ALICE systems map, with a step-by-step introduction, is at hlf.kumu.io/alice-systems-map. You can go directly to the map at kumu.io/hlf/alice.

The overall ALICE map is one way to help understand the challenges these families face. It is especially valuable because it identifies the negative feedback loops that reinforce a problem and the positive feedback loops that might help solve it. Maybe most important of all, the map can help nonprofits identify key places in the system where social service action and spending might help the most.

The Aloha United Way and other nonprofits use the map to help them focus on prevention and identify high leverage points where spending “a dollar would have maximum impact,” says Cindy Adams, president and CEO of AUW.

The map was created with the help of the Hawaii Leadership Forum and Sam Dorios, the forum’s systems and complexity associate, with input from ALICE households and the agencies that support them, Adams says. She says the map continues to evolve as more is learned.

━━

Needed: A Comprehensive Solution

Leaders of the Aloha United Way say no single fix will solve the problems of Hawaii’s ALICE families. What’s needed instead is a multifaceted approach.

by Steve Petranik

Aloha United Way coordinated the creation of the Hawaii ALICE report with support from the Bank of Hawaii Foundation, the Hawaii Community Foundation and Kamehameha Schools. Hawaii Business Editor Steve Petranik interviewed three of AUW’s leaders: President and CEO Cindy Adams, COO Norm Baker and VP for Community Impact Elizabeth McFarlane. Here are condensed highlights of that conversation.

Petranik: The Hawaii ALICE Report is part of a national effort.

Cindy Adams

Adams: Eighteen states have published ALICE reports that cover more than 60 percent of the nation’s population. The data starts in 2007 and works forward to track how well households have recovered from the Great Recession.

The systems map (detail is shown on the previous pages) helps to explain Hawaii’s ALICE households’ challenges. The map is informed by community input from a broad cross-section of stakeholders, including ALICE individuals and families. It is a living document that will evolve as we learn from collaborating with nonprofits and work with ALICE households. Some loops have already been revised to reflect learning that has taken place.

Aloha United Way has committed funding for three years toward an ALICE grant whose goal is to support financial stability and upward mobility of ALICE households. During the grant period, we will learn more about where the map’s assumptions were correct or maybe underdeveloped. We will make adjustments to the map and, more importantly, improve upon the work we are funding in the community.

Elizabeth McFarlane

McFarlane: The map shows key areas where change can be leveraged. If we can support the financial well-being of a household, we know that the

ripple effects going forward are substantial: for health, for education, for long-term employment outcomes. There are benefits across the life-course for individuals, and the potential to influence the inter-generational impacts of disadvantage which is a benefit to all of us in Hawaii.

A significant underlying factor is the growing cost of living in Hawaii and the squeeze that it puts on all citizens, but particularly for ALICE families.

A Scarce Treasure is Time

Petranik: Can you give an example of something you reconsidered?

Adams: One assumption was, given the opportunity, that adults in ALICE households would want to go back to school, finish a degree or learn new skills to increase their household income. In fact, we found that the majority were not interested in going back to college or allocating extra time to skill development because it was more important to spend time with their family and children, which was already very limited.

Norm Baker

Baker: The ALICE families understood that a large part of their children’s quality of life and their own quality of life was their time together. And they wanted more of that, the reward of being together. This meant a lot to them.

Adams: Parents work long hours and odd hours, often on weekends. There is some sense of guilt when you don’t have time to be with your children. This is universal, but this was a very basic loss for these parents, like one more thing they couldn’t give their children.

Baker: Another interesting thing came up in interviews with ALICE families. They didn’t say they were happy with where they were at. What they said was, “I’m accepting of where I am at, but I want something better for my kids.” That was almost universal. They had a real, real heavy focus on their children.

Another thing that our mapping of the ALICE families “system” clearly identified for us was places where the system was frozen, where there is very, very little that can be done to it. From our perspective, those were areas where we wouldn’t want to invest dollars because obviously you’re not going to get as much impact.

One of those frozen areas is the whole issue of government support and government benefits and how difficult that is for people to navigate these systems. Government support and assistance is more abundant for poverty-level households than the ALICE population, but even the ALICE population can benefit from many of those government support programs. Once again, it’s a time issue: The time it takes to work their way through that system is overwhelming.

Take-home Pay

Adams: There’s a sensitivity among businesses about raising wages and compensation. This is understandable. The solution to ALICE is not just about compensation. It includes addressing the high cost of living in Hawaii. We cannot pay people enough to get ourselves out of the high cost of living cycle. We must address housing affordabililty. Housing is the single largest household expense. The second is the cost of child care and preschool. If we can address child care, parents will have more flexibility for upward financial mobility and this will help break multi-generational cycles of poverty. The same with access to preschool.

The big challenge is coming together as a community to look at all these issues within the context of a dynamic system instead of as independent problems. We have to figure this out.

Other Solutions

Adams: One thing businesses can do is something we challenged ourselves with at Aloha United Way. What could we do in the way of a benefits package to help address some of our employees’ household needs? We made paid time off flexible, meaning not just for use when the employee gets sick, but allows the employee to take time off if the child is sick, or if they are a primary caregiver for somebody else in their family. Another example was allowing flexible work hours so employees could coordinate their work schedule with lower or no-cost child care.

━━

Part 2: Possible Solutions

Four strategies that can help ALICE families

by LiAnne Yu

There are many efforts to support ALICE families, but people disagree on some of the proposed solutions.

For example, some people argue that short-term rentals for tourists are a problem, taking homes out of circulation and raising rental prices for locals. Others say Airbnb rentals provide critical extra income for working families.

Some argue we must increase the minimum hourly wage to at least $15. Others say this would make it harder for small businesses – many owned by ALICE households – to compete.

Some argue for raising taxes on investment properties owned by residents of other states and countries to pay for housing and education. Others believe the costs would just be passed down to tenants and local consumers.

Cindy Adams, president and CEO of AUW, emphasizes there simply is no silver bullet. “Helping ALICE and our community and helping our families is a multifaceted issue. It’s compensation. It’s affordable housing. It’s affordable child care. It’s free preschool. It’s better benefits from our employers. It’s all of those things. But what is important to understand is that we can’t fix ALICE on just the back of one piece of that puzzle.”

Gavin Thornton, co-executive director of the Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice, suggests that instead of focusing on what’s right in front of us, we step back to identify the more fundamental issues. He uses an analogy to illustrate. “You’re standing on a river bank and someone comes down the river and they are drowning. You jump in and save them. Later on, you see someone else going down. You jump in again. And it keeps going on like that: You keep seeing people drowning, you keep jumping in.

“But what if you actually walked upstream to figure out what was causing this to happen? How is it that we’ve gotten to the point that 48 percent of our families are a paycheck away from homelessness?”

In this section, we explore four ways forward that some local leaders have identified.

1. Be willing to disrupt old processes

Last Christmas, Faamamamika Vaesau and his wife were living in a homeless shelter with their three children. Their two jobs were just not enough to cover rent and groceries. This Christmas, things are different. They live in a two-bedroom place with rent he can afford, neighbors who help him watch his kids, and a new job that pays him $5 more an hour than his previous one. He’s even able save a little at the end of the month.

“We couldn’t celebrate Christmas for so long because all the money went toward the bills. This was the first year my kids got to have a tree and presents. To see them so excited, I felt so happy. And, to be honest, I felt so happy I started to cry,” says Vaesau.

What turned things around for him was the chance to live at Kahauiki Village, which provides permanent affordable housing to working families who were once homeless.

Faamamamika Vaesau and his family | Photo: Elyse Butler

The story of Kahauiki Village is, in many ways, the story of how different groups disrupted the typical inertia for the sake of doing something extraordinary together. It starts with catalyst Duane Kurisu, who was deeply moved by the plight of homeless people in Hawaii and wanted to help develop more affordable housing. (Disclosure: Kurisu is the owner of Hawaii Business.)

Instead of slogging through the usual process, Kurisu took advantage of an emergency proclamation allowing government agencies to be fast-tracked through the bureaucratic process. In essence, as he describes it, government provided free land, got approvals completed quickly and provided infrastructure. The private side took on the financial risk and brought agility and creativity to the project.

“I cannot overemphasize the importance of a public-private partnership,” says Kurisu. “Government cannot do this alone and the private industry cannot do it alone. It has to be done together and it needs to start from a standpoint of trust.”

Others volunteered their time, donated resources and provided expertise. Even outsiders were persuaded to provide support. For example, Japanese manufacturer Komatsu donated modular homes and Tesla provided the batteries that allowed the development to function off the grid.

The Vaesaus at their current home in Kahauiki Village | Photo: Elyse Butler

“The amount of giving that came from people, both in monetary terms, but more importantly from their hearts and from the energy that was given to the project, exceeded all of our expectations. I think what we saw was that people want to help. They just need a way to help,” says Kurisu.

Inspired by memories of the plantation culture he grew up in, Kurisu envisioned an environment where people could live in dignity and in community. To that end, the village includes a day care, preschool, laundry, grocery store and community garden for people to learn how to grow food.

Many hope Kahauiki Village is a model that others can follow. “When people say we can’t build affordable housing in Hawaii, that’s baloney. We can,” says Marc Alexander, executive director of the city and county of Honolulu’s Office of Housing. “Not only that, he (Kurisu) did it. It’s our proof of concept. When people say public-private partnerships can’t work, that’s also baloney. There is the example.”

2. Design solution systems, not just fixes

Lourdes Maquera works 15-hour days at two different housekeeping jobs. Her commute between Waipahu and Waikiki eats up at least an hour each way. Most of the week, she’s away from home from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. When she’s running late she’ll drive, but parking can cost $20. Such expenses can mean the difference between making ends meet or having to pay groceries on a credit card.

If Harrison Rue’s vision for the future of transportation comes to pass, commuters like Maquera won’t have to spend that kind of money or time getting to and from work. Rue is the administrator of Honolulu community building and transit-oriented development.

At the heart of his vision is rail. As Rue explains, we shouldn’t see rail as an end in itself but as a catalyst. It will spur development in housing, and at least a portion of that will be dedicated to affordable options. It will drive investments in sidewalks, parks and sewer lines. It will bring more bike sharing and ride-hailing services. It will reduce the number of parking garages needed, potentially opening up their use for more housing. It will make apartment buildings more affordable because they will no longer need as much parking.

In this future, Maquera could save as much as $10,000 a year – the average cost Hawaii residents pay for car payments, maintenance and gas.

“When I grew up in suburbia, the car was freedom for me,” says Rue. “But now the car is a ball and chain around the neck of somebody. Especially if it comes down to whether I can afford my own place versus crashing on my uncle’s living room couch.”

Aki Marceau, managing director of the Elemental Excelerator, sees rail as the first of the interconnected services that will make life better for ALICE families and bring Hawaii closer to its goal of using 100 percent renewable energy sources by 2045. She points out the state currently spends $5 billion every year to import crude oil to power our cars and produce electricity. When all of our energy is created entirely within the state, energy bills such as Maquera’s will go down – currently hers is at least 2.5 times more than the average person living on the Mainland.

The clean economy will also create an estimated 3,500 new jobs every year, paying on average $3-$7 more than the median wage today, says Marceau. These will include roles in construction, solar panel installation, wind-farm maintenance, data reading and coding. Most of these, Marceau says, will require training but not necessarily a college education, making them attainable for most people in society.

“I believe we can actually design the future that we want to live in. We shouldn’t let technology just happen to us. We should harness technology and innovation to achieve the type of world and type of communities that we’re trying to achieve,” Marceau says.

“We’re going to be a postcard from the future about how we mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change. And with that will come higher paying jobs for so many people.”

3. Support our youth

Every day, Kalihi public school teacher Nicole Schubert sees how financial distress impacts her students’ ability to envision their futures. “We’re pushing college on these kids, but I don’t think they can fathom picking up a student loan or leaving the state to go to school. Those things are hard for them to visualize because their whole family has lived here their whole lives, or maybe their parents are from Micronesia and never went to college. And so it’s hard for many of them to picture anything but going into low-wage jobs like their parents.”

Kamehameha Schools’ VP of strategy and innovation, Lauren Nahme, describes this cycle of poverty: “Having household stresses affects education priorities, and it affects their readiness to learn when they go to school. They are experiencing lack of connection and mentorship at home because parents are stressed out or maybe there is only one parent or no parent. A really big part of financial stability is having asset ownership and health that you can transfer from generation to generation. The less base you have, the less you’ll prioritize higher levels of education, especially if there are costs involved.”

YouthBuild, a program funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, seeks to break that cycle by offering 15-25-year-olds from low-income families the opportunity to complete their GEDs while simultaneously gaining job training by constructing 400-square-foot residential units. What makes this program even more relevant when it comes to solving the ALICE challenge is that the homes these youths build will be reserved for low-income renters.

“It’s hard for many of them (students) to picture anything but going into low-wage jobs like their parents.”

– Nicole Schubert, Kalihi public school teacher

“The goal is that when the students are done with our eight-month program, they have OSHA, forklift and other certifications under their belt, so they can get jobs in the construction field. But at the same time we’re working with these at-risk youth, we’re also addressing the affordable housing issue,” says interim project manager Mona Bernardino.

Terrence George, president and CEO of the Harold K. L. Castle Foundation, says one way to reduce the number of ALICE families is to show students the connection between education and higher salaries. “There’s national data that shows that if you get a B.A., your lifetime earnings are $1 million more than if you just had a high school degree,” he says.

His foundation supports partnerships between educators and high growth industries, early college work in high school, project-based cultures in schools, field trips to job sites and student apprenticeships.

George’s goal is to empower students with all of the tools and exposure they need to make the best decisions for themselves. “For example, there is plenty of demand for certified nurses in our state. But on those salaries, you may stay ALICE forever. However, if you train to be a nurse for an anesthesiologist, while there may not be as many jobs in the state, you will be able to make a lot more.”

He adds, “If you ensure there’s strong educational opportunities for all, that are reasonably affordable, and lead persons to those life skills they need to lead, we will chisel away at the forces that continue to divide us and make the middle class wither away.”

4. Strengthen workers’ voices and civic engagement

When I first spoke with Rob Valera, the maintenance engineer was 26 days into what would eventually become a 51-day strike at the Sheraton Waikiki. He was also just one payment away from being delinquent on his mortgage. “It’s really scary to know you could receive a letter saying you’re one step closer to foreclosure. I get chicken skin every time I see the mail.”

Despite that fear, he believed it was important to keep up the strike. “I’ve put nearly 20 years of my life into this company. It’s my second home. I spend three hours in traffic every day to get to work and back home. So I’ve got to take care of it, got to take care of the others I work with. And in return, I feel like our employers should take care of us.”

The fundamental problem, Valera and other strikers expressed, is that the biggest companies in Hawaii are increasingly being run by stakeholders who aren’t from Hawaii, may never have lived in the state and thus have little connection to their employees.

For Valera and the others, organizing and speaking with one voice was the best way to be heard. “The benefits and wages we get from employers were never given to us. They were fought for by generations before me. We’re not going to be the generation that gives in,” he says.

After the longest hotel workers strike in Hawaii since 1970, the union negotiated a total increase of $6 across wages and benefits over the next four years. Just as important for the union members were the wins on job security. If the employer wants to introduce new technology that potentially replaces employees, they must notify worker committees, which then have a chance to negotiate retraining for other departments or fair severance packages.

“The word solidarity can seem abstract, but the unity was just something I’d never seen before,” says Paola Rodelas, Unite Here Local 5 communications and community organizer. “We had very few workers actually cross the picket line. It was less than 1 percent of the 2,700 workers. That, to me, was really inspiring.”

Rodelas describes the model of collective action as one everyone should practice, not just union members. She recalls a retiree approaching her in tears because her low income senior housing rent was about to be doubled. The woman wondered if Rodelas could help organize the other residents to come up with a plan of action. Rodelas agreed but didn’t expect much participation. She was shocked to find 60 senior citizen residents gathered and waiting for her.

“They did all of it themselves,” she says. “They organized. They picketed in front of the building to draw attention to the issue. All I did was get the media there. And in a matter of weeks, they got the governor to step in and say, your rent is not going to double.

“For me, that’s a testament to how at the core, we need to get organized. Beyond just wages and benefits, what would our community look like if, say, we as renters organized? The lesson that we can derive is the power of what happens when working people get together and demand things not just for themselves, but for everyone.”

━━

Some Numbers Can Be Deceptive

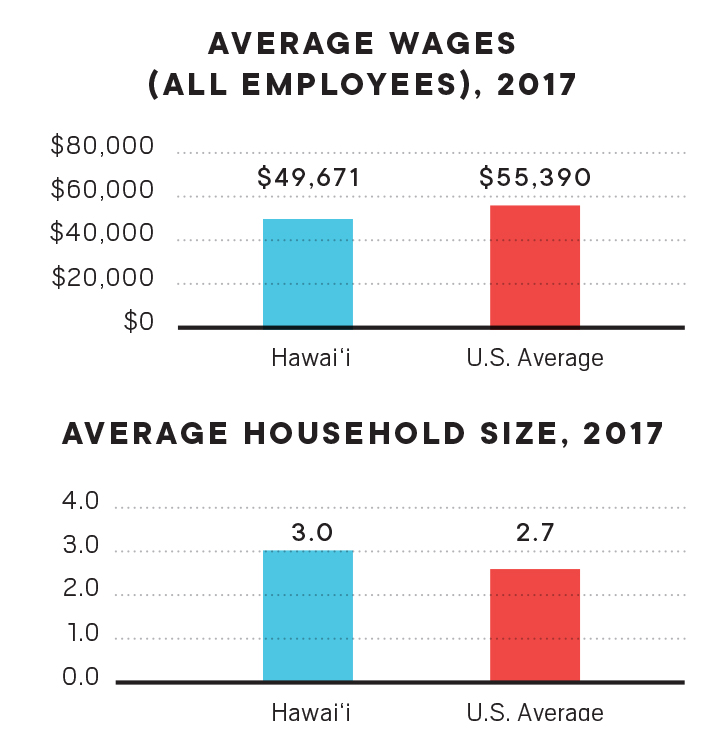

Hawaii’s average annual household income of $77,765 was the fourth highest in the nation in 2017.

But Hawaii’s average annual wages per earner were $49,671 – that’s below the national average. How is that possible? Hawaii has the nation’s second-highest average household size; high housing costs often persuade multiple earners to live together in a single household to make ends meet.

━━

Lower Income Workers Fall Further Behind

About half of Hawaii’s residents have seen their income go down over time. From 1980 to 2015, earners in the 50th percentile of annual income suffered inflation-adjusted income declines of 1.5 percent, while earners in the 20th and 10th percentiles fared worse: income declines of 3.0 percent and 6.1 percent respectively.

In the same period, earners at the 80th and 90th percentiles experienced increases in income of 3.0% and 7.7%.

━━

Part 3: What Can I Do?

With so many needy families, businesspeople can feel overwhelmed by the issues that defy easy solutions. But the leaders we interviewed stress that even though the challenges are complex, our individual responses don’t have to be. Here are three principles to follow if you want to help.

by LiAnne Yu

1. Do What You Do Best

Businesspeople may hesitate to weigh in on poverty and social justice issues, believing these are the exclusive domains of nonprofit and community experts.

To the contrary, Hawaii’s leaders urge businesspeople to get involved and bring their entrepreneurial instincts into play. “Businesses can roll up their sleeves and say we’ll bring concepts and solutions to the table for consideration, and strategies for implementing them. After all, that’s what a lot of businesses are good at,” says Colbert Matsumoto, executive chairman of the board at Island Insurance Cos.

Supporting entrepreneurship is one way that businesspeople can help youths from ALICE households potentially break the cycle of poverty. Donavan Kealoha was born and raised in Hawaii. He worked for many years in a Silicon Valley venture capital firm and wondered why there weren’t more people who looked like him in the tech field. To rectify that, he co-founded Purple Maia Foundation, which provides after-school classes in coding and computer science to Native Hawaiian students, low-income youth and others underrepresented in tech fields.

He describes one former student – a shy girl with family challenges who had dropped out of school. She took instantaneously to the coding class and whizzed through the curriculum, got into a more advanced coding boot camp, and ended up helping out on a Microsoft project.

“I see students like that as future CEOs. As for me, I’m just trying to help these kids find their jam,” says Kealoha.

Catherine Ngo, president and CEO of Central Pacific Bank, urges the business community to do what it does best: leverage its connections to create more funding for young entrepreneurs. “I do think that there is the capital out there we can harness – plenty of local capital as well as outside capital from Silicon Valley and Japan, places that have natural ties to Hawaii. We need to make them aware of the number of ideas coming out of Hawaii that they can invest in.”

Another approach businesspeople should support is diversifying and upscaling our visitor economy so that employers can increase service worker wages, says Paul Yonamine, chairman and CEO of Central Pacific Financial Corp. He suggests designing more high-end experiences in wellness, culture, sports and cuisine to attract VIPs. “We do a better job than any other place in the world making people happy. But there’s still lots of work we can do to enhance the quality and value of what we provide in order to generate more money for local workers,” Yonamine says.

Business leaders can also volunteer their expertise. Mona Bernardino, interim project manager at YouthBuild, is looking for architects to help her students build structures that will be rented out to low-income residents. That will save them the $7,000 it takes to hire someone to help them place the structure on-site, connect to utilities and meet permit requirements.

“Businesses should not feel hesitant to be stepping into this space,” says Joyce Lee-Ibarra, president and CEO of JLI Consulting. “They should be asking themselves, how can we harness what we know we’re good at that could be of benefit to ALICE households? How can we be creative in thinking about not just financial costs, but other areas of need for ALICE households? How can we bring in our most experimental, innovative know-how?”

2. Support Your Own ALICE Employees

Give them a raise if you can. But Cindy Adams, president and CEO of Aloha United Way, says businesses shouldn’t think there is nothing they can do for their ALICE employees just because they can’t afford to raise their wages. Instead, she encourages businesses of all sizes to look for creative ways to offer other benefits that help employees become more resilient.

For example, reimbursement for educational enrichment, such as online courses, can help employees gain skills to advance their careers and earn more money. Plus your company could benefit from those advanced skills.

“Take an interest in helping people gain skills in financial management. Provide counselors who can help them understand how to save and how to contribute to a 401(k) – the kind of stuff where they can learn how to put away their money,” suggests Connie Mitchell, executive director of the Institute for Human Services. After all, more financially secure employees can focus less on mere survival and more on their jobs.

Lee-Ibarra describes one business owner who brought in tax assistants to help all employees file for the earned income tax credit. “I loved the creativity – this is really applicable to this target population, and something they wouldn’t take the time or have the mental bandwidth to seek out on their own.”

Offering full on-site child care is a large investment, but Barbara DeBaryshe, interim director at the UH Center on the Family, says there are less costly options: “You could offer space for child care, working with other businesses jointly to rent that space to a child care organization that would come in with their staff, licensing, health and safety, and curriculum. As another option, some companies offer child care vouchers, which is like an employee benefit that employees can apply to a child care of their choice.”

ALICE parents typically can’t afford full-time child care, often juggling work with picking up children and taking them to doctors’ appointments. Providing more flexible work schedules can alleviate the time pressure, as well as encourage families to not skimp on regular medical care. The option to work from home can also make it easier to care for a sick child or elderly relative.

Lee-Ibarra suggests simply asking employees what they need. “There are circumstances where people come up with solutions about a group that they’re not necessarily a part of. But really, the best way to find out is ask the people who are impacted what they need. Ask employees to come to the table for these conversations. They may not be able to generate immediate solutions, but they can speak to the lived experience of the problem that needs to be addressed.”

3. Remember, We’re All Connected

One of the most important things for businesses to do, says Peter Ho, is to realize that the well-being of ALICE community members is, in fact, our own well-being – not something that can be separated out and ignored indefinitely without consequences. “We can think of all sorts of incredibly fantastic, strategic ideas, but fundamentally the most important strategic element of our business has to do with the continued health of the community. Without that, it doesn’t matter what we’ve come up with,” says Ho, chairman, president and CEO of Bank of Hawaii.

“If you think of your own long-term viability as a business, you begin to understand that we have a vested interest in being part of the solution. We can’t just stay observers,” he adds.

Ho’s comment was echoed many times by other leaders. Colbert Matsumoto, executive chairman of the board of Island Insurance Cos., warns that if the situation doesn’t improve, the employees and customers of local businesses will leave the state for better pay and lower costs of living. “I see that as a drain of talent, an exodus of skills. We do a good job of raising our young people. But if ultimately they become one of our exports, we’re not going to be able to get them back.”

Paola Rodelas, communications and community organizer of the union, Unite Here Local 5, says that understanding such interconnectedness makes workers’ struggles and successes ultimately everybody’s. “Hotel companies are billion-dollar industries that aren’t even based in Hawaii anymore. It’s not the Hilton family that owns it anymore, it’s private equity. The only money we as a community get back from them is through our workers. When they are paid well, that’s money they spend back into the local economy and eating at local restaurants. Their tax money pays into our schools and services our state needs. That’s one reason why the business community should care.”

While Hawaii’s leaders want everyone to understand the gravity of the ALICE report’s findings and their impact on all of us, there is also a great deal of hope. That hope is largely based on the fact that so many local leaders understand our interconnectedness.

“We have advantages other places don’t have,” says Gavin Thornton, co-executive director of the Hawaii Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice. “We’re a relatively small community and we have the potential to address some of these complex problems just because of that. In a way it makes it easier to have the conversations about change and to effectuate the change so we can all thrive together.

“I do think we’re at a tipping point. I’ve seen a lot of positive changes in just the past couple of years, and the ALICE report has been a big part of that. It has really captured people’s attention. And there are people coming together in ways they haven’t done before.”

Ryan Kusumoto, president and CEO of Parents and Children Together, says the most encouraging thing he has observed is a shift in how the business community talks about the challenge. “We’re starting to see big business and for-profit entities coming in saying, ‘We can be a part of this solution because we get it. These are the people who are working for us, these are the people who are coming to our establishments to shop. And we need to be part of that solution because we’re Hawaii, we care about each other, we need to do that.’ So I think that’s a real bright spot we’re heading toward – a place where we can all be part of that solution because we understand it better,” Kusumoto says.

“And I’ve been starting to hear that shift. There’s less talk of ‘those people’ and more of ‘us.’ More of ‘we.’ More of how can ‘we together’ do this.”

What Are Your Solutions?

We’d love to learn on social media about programs you recommend that deal with these problems, other issues in your community and your overall thoughts on this CHANGE Report!

Please share your thoughts & suggestions through any social media channel & use the tag: #ChangeHawaii