Growing Up in an Age of Anxiety

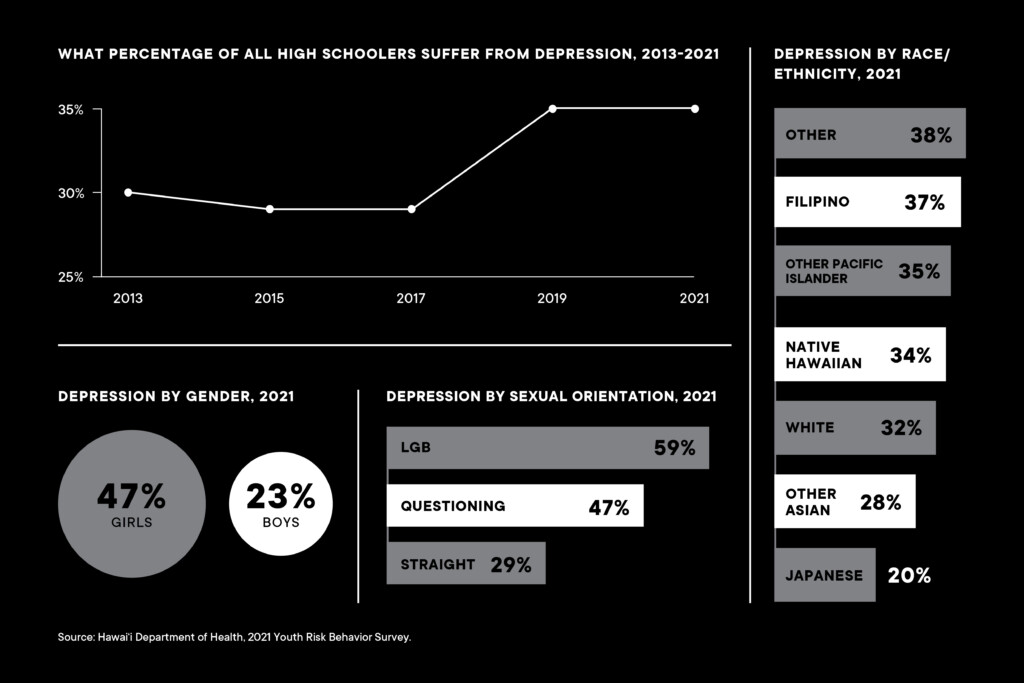

Hawai‘i’s young people are struggling with mental health issues. Nearly half of high school girls and 60% of LGBTQ+ students experience depression. And help can be hard to find.

Part 1: Mapping the Mental Health Crisis

The situation is dire but there are hopeful signs, such as the acceptance and effectiveness of telehealth therapy.

Jump to Part 2: The Rocky Path to Becoming a Mental Health Provider

Anxiety can feel like a squirrel in your head. Thoughts get stuck, circling over and over. The constant internal chatter makes it hard to slow down and calm your thoughts.

That’s how Chachie Abara describes it, as she recalls anxiously fixating on what other people thought of her. Insecurity may be a hallmark of youth, but hers felt unmanageable. “I was constantly obsessing about whether people liked me,” she says.

She says that need for assurance likely stems from being a shy child. She emigrated from the Philippines at age 7 and while she longed for close friends in her new ‘Ewa home, they were difficult to find.

As she grew older, social media exacerbated her anxiety and bouts of depression. Instagram can be the worst culprit, she says, as people “show off” in their postings, inviting comparisons.

At UH Mānoa, where she majored in psychology and Philippine language and culture, she finally understood what was happening. “I didn’t even know what mental health was,” she says. “In college, I learned the words and definitions behind what I was going through.”

She says that among her circles, “people struggle with peer pressure, conforming, not knowing what to do with their lives. We want to know what’s next.”

To deal with intense, often debilitating feelings, many of her peers use medication prescribed by doctors. Others turn to religion or spirituality, meditation and “trying to find and redefine yourself.”

Abara talks to a therapist, does free writing, practices mindfulness, regularly disengages from social media and maintains periods of silence. She says she’s on a “healing journey” after hitting a low point and seeking help from a crisis line.

Despite having a full-time job, working on a children’s book and running a Filipino-focused podcast called Kasamahan Co, she can doubt herself: Am I doing enough? Does the work I do matter?

She reminds herself it’s enough, that she shouldn’t push so hard. But projects have a way of pulling her in. The latest is launching a Hawai‘i chapter of the San Francisco-based Filipino Mental Health Initiative, where she hopes to reach high school and college students, building awareness and delivering the message that they’re not alone.

Throughout the Islands and across the continental U.S., at every income level, vast numbers of young people say they are anxious, depressed and thinking about suicide.

Teenagers in Distress

The youth mental health crisis has been brewing for years, starting at least a decade ago and accelerating during the long, lonely pandemic months. By 2021, a rare Surgeon General’s Advisory was issued, calling it an urgent public health issue.

In February of this year, alarm bells went off again when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released the results of the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 42% of high schoolers experienced persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness in 2021, up from 28% in 2011. And 22% were seriously considering suicide, up from 16% a decade earlier.

Among girls, those numbers were worse: 57% said they felt so sad or hopeless for a stretch of time that they stopped doing their usual activities. For LGBQ+ students, 69% felt that way. (Data specifically on transgender students wasn’t captured.)

Even gloomier, about 30% of high school girls said they were contemplating suicide, as were 45% of LGBQ+ students. These are far higher numbers than those for boys and straight kids, and higher than any single racial or ethnic group, including Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

In April, the Hawai‘i Department of Education and Department of Health released their own data collected for the national report. The Hawai‘i Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which was administered to middle and high schoolers in spring 2019 and fall 2021, found distress levels were slightly lower than national averages, but still worrisome.

Among public high school students across the state, 35% said they had experienced at least a two-week stretch of sadness and hopelessness – 7% fewer than national results. And nearly 17% were seriously contemplating suicide – 5% less than the national figure.

When the data on girls are broken out, the numbers jump. About 47% of high school girls in Hawai‘i suffered from depression during the survey period, and about 23% had suicidal thoughts. Among middle school girls, an alarming 35% had suicidal thoughts.

For LGBQ high schoolers in Hawai‘i, 59% experienced depression and 39% had suicidal thoughts.

A broader segment of the LGBTQ+ population was surveyed in 2022 by the Trevor Project, a national suicide-prevention organization. That survey found that 75% of LGBTQ+ people in Hawai‘i, ages 13-24, reported symptoms of anxiety, 53% had symptoms of depression and 52% were seriously considering suicide. A full 17% had attempted suicide in the past year.

Compared to national rates for people of all ages, Hawai‘i has relatively few deaths by suicide, ranking 40th. But among teens 17 to 19, Hawai‘i has the 19th highest rate. Of the 47 young people who died by suicide between 2016 and 2020 across the state, 66% were in the 17-19 age range and 74% were male, according to data from the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division of the state Department of Health.

Some teenagers in distress have sought out immediate help. Since launching in 2013, about 3,600 people ages 13 to 17 have used the crisis text line from the 808 area code, according to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division.

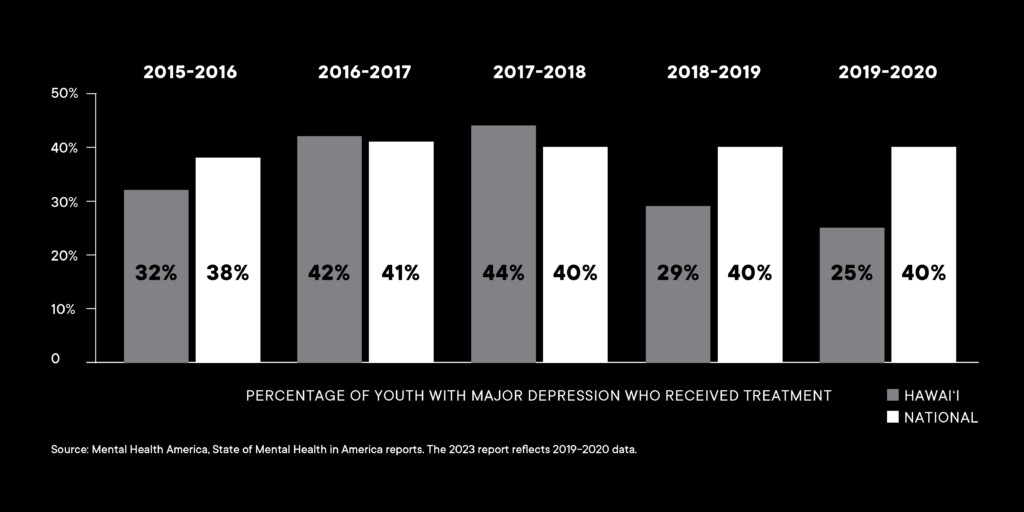

But that represents just a tiny fraction of young people needing assistance. Recent data from the advocacy group Mental Health America shows that Hawai‘i ranks near the bottom in accessing services: 75% of youths with major depressive symptoms have received no mental health services.

What Therapists See

The high incidence of teens reporting mental health issues doesn’t surprise Joy Tanimura Winquist, a private-practice therapist in Kaimukī. She left nonprofit and government settings to open Pūlama Counseling in 2021, and her appointment book quickly filled up. She treats mostly children and teens, and particularly girls.

Adolescence, of course, is a time of intense emotions, filled with crushes, rivalries, slights and elation. Feeling anxious or sad is not inherently bad, says Winquist. “But clinical anxiety or clinical depression, that is when we’ve gotten a little outside, gotten dysregulated, something feels too big, too hard in those moments.”

In her practice she sees a lot of clinical anxiety and depression, as well as undiagnosed ADHD, which can lead to academic struggles and self-criticism. “Then there’s the continued pressure of getting good grades and, unfortunately, with the high schoolers, a lot of them have had some type of negative sexual encounter,” says Winquist.

Many of her clients with anxiety have been raised in households full of worry – they absorb the anxiety of their parents, which was only intensified by the pandemic.

“The grown-ups were so anxious, it was hard not to take it on,” Winquist says. “The kids assume it’s because they’re defective,” a narrative that can lead to depression.

Psychologist Gerald Brouwers, Ph.D., agrees that parents are contributing factors. “One thing I like to say is that anxiety is a contagious disease,” he says. “It’s often transmitted in families, so if you’ve spent a year and a half at home with mom and dad, that can mean their stress also impacts the kid’s stress.”

Brouwers brings decades of experience as a psychologist to his busy private practice in Mānoa. About 40% of his client base are teenagers. Many of them attend surrounding private and public schools and are part of a more affluent Island demographic.

Like Winquist, he sees many kids with anxiety, depression and ADHD, and he helps them recognize the stressors in their lives and find ways to relieve stress or to change their perceptions of why “everything feels so horrible.”

Some of those feelings come from pressure to achieve. “Parents and schools communicate expectations in a lot of ways,” Brouwers says. “If you’re on the downside of that performance scale, then you get more anxious because you’re falling farther behind. It’s not a good place to be. It contributes to depression and people feeling overwhelmed and helpless.”

Ultimately, he’s not especially worried about young people, and takes the long view that comes from knowing that the disruptions of adolescence usually subside with maturity. He says adults’ concerns about younger generations are as old as Aristotle, who wrote in the fourth century B.C. that all of their mistakes are due to excess and vehemence and their neglect of the maxim, never go to extremes.

But the long view can be hard to absorb when you’re deep in the social dramas and academic demands of many of Honolulu’s public and private schools – the latter which enroll about 8,000 high schoolers, according to 2021-2022 data from the Hawai‘i Association of Independent Schools.

One student, for example, is a striking, articulate high schooler who wins state awards and has loving parents. From the outside, her life looks enviable, laid out like stepping stones on the path to an ideal adulthood: college on the mainland, graduate school, rewarding job, family.

But in her mid-teen years, that’s not how she sees it. The pressures of her private school can make her sad and anxious, says her father, and she’s often holed away in her bedroom in the evenings and on weekends. It gets so bad that she sometimes can’t keep food down, and her thin frame can take on a gaunt cast. She lashes out at him frequently.

Despite her achievements, she never meets her own expectations. She compares herself to an older sibling and is determined to follow the same career path, whether it suits her or not. (Names and identifying information have been removed at the parents’ request.)

Another teen from Honolulu comes from a similarly caring and comfortable home. He graduated from high school with exceptionally high test scores and rare technical gifts.

But after a year of college in a northern mainland campus, the remoteness and scarcity of light – with the winter sun setting in the late afternoon and dense clouds creating a funereal gloom – have been hard to adjust to.

Some older difficulties persist as well, including trouble reading social cues and anxiety about what the future holds and how to deal with uncertainty. He tells his mother that three more years there feels impossible.

Anxiety in College

At UH Mānoa, the Counseling and Student Development Center gives many students their first chance to independently access mental health services, without getting a bill or fielding questions from parents.

Every student gets six online sessions a year, a number capped by the center’s limited pool of mental health professionals. Students in crisis, however, get immediate interventions, and those with more extensive needs are given referrals, though a shortage of providers can make it hard to find openings.

The past year has been busy, says psychologist Alexander Khaddouma, Ph.D., a coordinator of clinical services. The UH center sees the same trends as mainland campuses, with the rates of anxiety and depression continually creeping up.

A 2022 report from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health shows that 65% of students visiting a campus counseling center in the 2021-2022 school year had anxiety – up 10% from a decade ago. About 46% had depression, which is slightly more than 10 years ago.

Generalized anxiety is the most common concern. A frequent scenario, says Khaddouma, is a student who feels sad, unmotivated, constantly fatigued and is skipping classes. “What brought them in is that they’re worried about their academic functioning, but really it brings up this mood issue they’ve been struggling with.”

Others come to the UH center with social anxiety. “They’re nervous around other people, having agitated thoughts where you can’t clear your mind and stay calm,” he says.

The steepest 12-year increase was among people with social anxiety, according to the national collegiate report, particularly the concern that “others do not like me.” The report speculates that isolation, social media comparisons and weak social skills – stunted by the pandemic – could be driving the increases.

Khaddouma says he sees all of those factors in the students he tries to help, on top of the heightened academic demands, stresses of college and lingering trauma from the past several years. Some of the students’ anxiety is in response to turmoil in the world, whether it’s political instability, gun violence or eroding rights.

For young adults, in particular, distress about the state of the nation is far from trivial: 53% of people ages 18 to 34 – the youngest group surveyed – said it made them consider moving to a different country, as did 59% of LGBTQ+ respondents, according to the Stress in America 2022 report from the American Psychological Association.

And there’s another issue that nearly everyone interviewed mentioned, which is simply the visibility of mental health issues today and the willingness of young people to talk about them.

“People are using a more therapy-focused language on social media. They’re using words like anxiety and trauma and depression,” says Khaddouma.

“Is that a good thing, or does it mean we’re watering down these pretty serious conditions that really affect people?” he asks. “My experience has been that it’s good for folks to have the language to describe how they feel.”

Public Schools Take Action

Hawai‘i’s public schools have spent the past year actively trying to boost students’ well-being, and many behavioral health professionals hope the new attention on mental health will spur lasting change.

“We don’t want mental health to go back into the background again,” says Ayada Bonilla, a school-based behavioral health educational specialist in the Office of Student Support Services of the state Department of Education.

Across the school system, the department has rolled out mental health screenings and is monitoring students, and it’s trained faculty and staff to spot warning signs – for example, students who are isolating themselves or whose grades have suddenly dropped. These “internalizers” can be harder to identify than the “externalizers” who are regularly sent to see counselors and administrators, says Bonilla.

“We want a larger network of individuals who are having their eyes on the students,” she says, stressing that when students have someone they trust at school, they’re more likely to open up and share their worries.

“The biggest screener that we have is day-to-day boots on the ground of adults building solid relationships with students,” agrees Kevin Cochran, a behavioral health specialist at Kohala Middle School on Hawai‘i Island. “And that goes for every adult, from the bus drivers all the way up to the principal.”

Students can also turn to a new, and free, online therapy program from Hazel Health, a San Francisco-based telehealth organization that has partnered with Hawai‘i’s public schools. Through the program, students can talk to therapists during the school day or from home.

Since launching in April 2022, more than 1,000 students have used this supplemental option, according to Fern Yoshida, student support section administrator in the Office of Student Support Services. While teletherapy has its critics, multiple studies show that it’s effective and that many young people prefer it.

Christina Swafford runs individual and group therapy sessions online through the Hawai‘i Center for Children & Families in Kapolei – practical training required for her master’s degree in mental health counseling at UH Hilo. She says telehealth has been an adjustment for her but not for young people.

“The kids are just totally acclimated to it. We actually tried to do in-person groups, and there wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm,” says Swafford. For those with limited access to in-person therapy, it can be the only realistic option.

Lauren Canton, another behavioral health specialist at Kohala Middle, says: “I’ve found it incredibly helpful, especially being in a rural, isolated area. We don’t have many clinicians in our small community. Parents have to drive 45 minutes to an hour to meet in person with a therapist, so Hazel really helps with accessibility.”

Few Hawai‘i Youths Get Help With Depression

Only a small fraction of youths ages 12-17 get any mental health treatment for major depressive symptoms. Here’s how Hawai‘i stacks up against national averages.

The state Department of Education is also rolling out programs targeting social-emotional learning, which focuses on the soft skills that underpin success in school, such as managing emotions, sustaining relationships and setting goals. Many of these programs are funded with federal pandemic dollars that began coming into schools at the start of the 2021-2022 school year.

To track progress, students complete a new social-emotional survey three times a year. Results from the winter 2023 self-assessments, completed by 66,500 students in grades 6-12, show tiny strides since the first survey in the fall.

But students are starting from a vulnerable position. In most categories – including self-management, grit, growth mindset and sense of belonging – Hawai‘i students are still in the 20th to 39th percentile nationally. (Elementary school students, however, scored significantly higher.)

Among individual schools, social-emotional learning takes many forms. At Kailua High School, for instance, behavioral health specialists Shion Pritchard and Cassidy Lasalle opened a wellness room on campus. It’s a soothing space where students can work on self-regulation skills and connect with the support team.

The team often helps students with social anxiety, says Pritchard. “They don’t want to get out of their cars when they come to school; they’re just really worried about going outside,” she says. In one example, she helped a student overcome intense fears of interacting with peers and walking through hallways.

Through two years of exposure therapy – adding small doses of a feared activity to incrementally build confidence – the student progressed from taking all courses in a single classroom to moving from room to room. In a breakthrough moment, the student recently presented a project to a panel of judges.

School counselors and behavioral health staff maintain a core focus on helping students like the one in Kailua. All told, they work with about 8,000 students with intensive needs in Hawai‘i’s public schools.

“We really have this wraparound continuum of care for a large number of students,” explains Bonilla from the Office of Student Support Services. Among the staff are behavioral health specialists, social workers, clinical psychologists and mental health counselors.

“I think Hawai‘i is in the vanguard,” says Kohala Middle School’s Cochran. “I don’t know many other states that have clinical people that are in the schools, getting to see students every day. The amount of progress that we can make and the amount of support that we give, being housed in the schools, are immense.”

Help for LGBTQ+ Youth

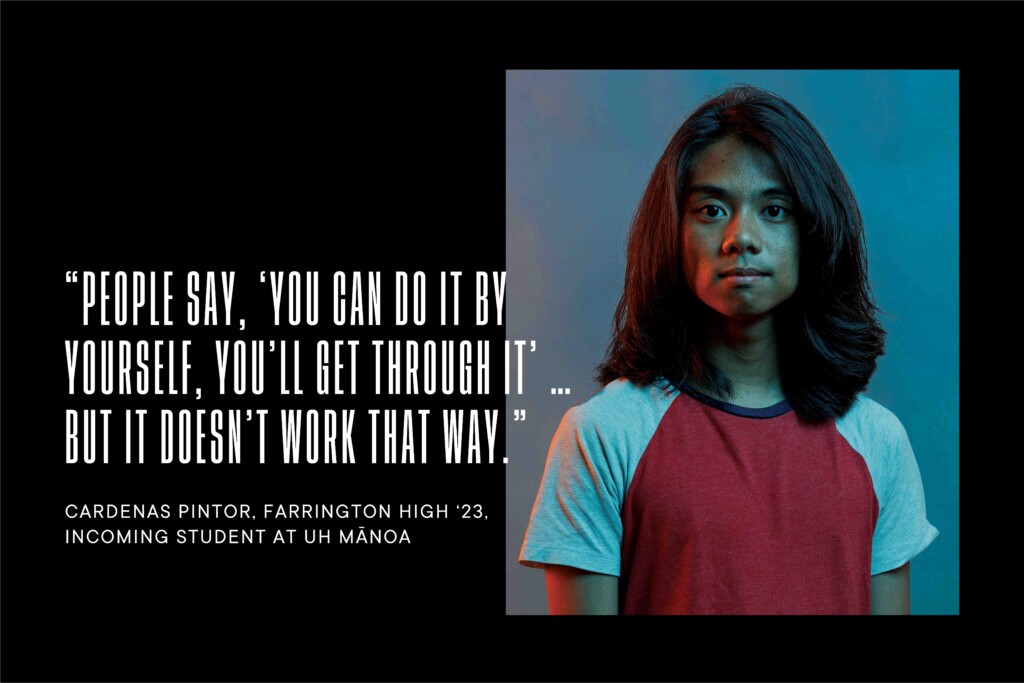

At Farrington High School, Cardenas Pintor found more support and acceptance than they ever did in Catholic schools. It was a relief to switch to a public school with a supportive Gay-Straight Alliance and caring social workers.

“The social workers have always been there for me and other students,” says Pintor. “They are way more accepting than the Catholic schools, and they understand that they need to help those being oppressed. They may have saved a lot more lives than we know about.”

It hasn’t been easy being a queer, agender teenager in Kalihi-Pālama. “I was raised around the thought that being gay or transgender would be punishable by God, and I would be sent to hell,” says Pintor.

The baggage of that upbringing and the challenges of anxiety and gender dysphoria can weigh heavily, but Pintor is well-informed and proactive in seeking help from Farrington’s LGBTQ+ support group, school personnel and outside mental health professionals.

“In Kalihi-Pālama, you experience these ways of thinking,” says Pintor. “People say, ‘You can do it by yourself, you’ll get through it, just carry on.’ But it doesn’t work that way, especially in Asian and Pacific Islander cultures, where everything happens in a community. If one falls, everyone falls.”

Pintor says a lot of students at Farrington have undiagnosed anxiety, depression and suicide ideation, and don’t know how to process their feelings properly. They encourage students to take advantage of school resources and to tap their family’s health insurance plans for therapy.

Under Hawai‘i’s consent law, people 14 and older can access mental-health counseling without their parents’ knowledge or consent, and insurers billed by therapists are prevented from sharing that information.

But few young people seem to know about these privacy rights. The Trevor Project’s 2022 report on LGBTQ+ youth in Hawai‘i found that 61% said they wanted mental health services but didn’t get them because they were afraid to ask their parents. Among survey respondents, only 19% said they had a high level of support from their families.

In Pintor’s family, there’s love but not enough support, they say. “But my parents are willing to learn who I am, and I hope they can understand I am unable to change and be the ‘perfect person’ they want me to be.”

Pintor graduates from Farrington in May with both a high school diploma and an associate degree in liberal arts from Honolulu Community College. They’re looking forward to pursuing social work at UH Mānoa in August and taking advantage of the wide-ranging offerings of a large university, such as women’s studies, gender studies and psychology.

“I’m very excited to see what the future will hold,” says Pintor.

Impacts of Social Media

In the mental health world, social media is a paradox: It’s the primary means that young people connect with one another, yet for some, especially girls, it can also be a nonstop triggering device that follows them everywhere, including their bedrooms.

But how much it contributes to escalating rates of anxiety and depression remains an open question. There’s no hard, definitive data about the harms of Instagram, for instance, and expert opinions vary, though the U.S. surgeon general warned of social media’s risks to young people in a May advisory.

Teens themselves say social media has a positive or neutral impact on their lives. In a recent Pew Research Center survey of 13- to 17-year-olds, only 9% said social media has a negative effect on them personally, though 32% said it has a negative effect on other teens.

Christina Swafford, the UH Hilo master’s student, was 11 when Instagram launched, so she is used to inhabiting a digital space, and the young people she counsels have never known life without social media.

Swafford’s view is that the upsides outweigh the negatives. “There’s a strong sense of community on social media,” she says. “It makes it so accessible to make friends who have shared experiences, or who have been through similar things as you.” She says many teens learn coping skills on social media.

Others are more ambivalent. Winquist, the private-practice therapist in Kaimukī, sees downsides but says there’s no going back. Social media was kids’ lifeline while classrooms were closed, and being online all day was encouraged by adults, she says. She advises parents to find balance when they’re setting limits.

At Child & Family Service, President and CEO Karen Tan is the oldest of the three women interviewed on this topic. She’s spent the past 18 years working at the social-services nonprofit based in ‘Ewa Beach, which helps about 15,000 people across the Islands. With three daughters in college and a team of 400 employees sharing stories from the field, she’s alarmed by social media’s impact.

Since Tan got her master’s degree from UH Mānoa in 1994 and began working professionally in Hawai‘i, she’s seen a dramatic change in the severity of issues young people face, including elevated levels of anxiety and depression, self-esteem issues and suicide ideation. She says social media is a major contributor as it adds pressure to portray yourself as perfect and shreds any sense of privacy.

“When we were in school, we would go home and the only people who came to our home were people we wanted there. Home was a safe place,” she says. Social media wrecks that security with its stream of potentially hurtful images and comments, and it becomes a false measure of worth.

“If someone sees how they’re valued based on the number of followers or likes … it’s almost like, I’m good if I get hundreds of likes, I’m bad if no one likes (my post),” says Tan. “Someone who’s already feeling down, it’s just pushing them down further, and they don’t know how to stop it.”

Trauma-Informed Care

The clinical definition of trauma, says Winquist, is a neurobiological response to a stressful event that impacts a person’s emotional and mental health. To make sense of how stressful events can layer upon each other and create lasting damage, she points to the groundbreaking ACEs study.

In 1995, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente introduced the concept of adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs. These can be fairly commonplace occurrences ranging from divorce and bullying to physical and emotional abuse to growing up amid chronic poverty or discrimination. The pandemic, by definition, is an ACE, says Winquist.

The more adversity a young person faces – especially without a caring adult at their side – the greater a person’s chances of experiencing toxic stress and trauma, which can manifest as anxiety, depression, behavior issues and poor physical health.

Trauma impacts many kids in Hawai‘i. At Child & Family Service’s four domestic violence shelters, Tan says staffers see many young people who have witnessed recurrent violence and been victims of sexual abuse in the home, the latter of which increased significantly during the pandemic, she notes.

Jamie Hernandez Armstrong, Ph.D., is the chief psychologist at the state Department of Health’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, which works with youths with serious emotional and behavioral challenges. She’s treated young people from Hawai‘i who were trafficked in the Islands.

“I worked with a number of youth who suffered horribly as a result of trafficking,” says Armstrong. “It’s interesting to me when people say, ‘Oh, that’s not real, that’s not really happening.’ Well I know it’s happening because I’ve seen it. And it doesn’t just happen to girls.”

Even far less severe experiences can impact brain development and impulse control, says Tan, which can make kids punch holes in walls or hit peers when they’re frustrated.

Tia Roberts Hartsock heads the newly created Office of Wellness and Resilience in the governor’s office. In this new role, she’s taking a sweeping view of all the ways that unaddressed stress and trauma are manifesting in the state and creating standards for trauma-informed care.

One example is kids who run away from home or school. “Oftentimes a split-second unconscious pathway in your brain triggers a response and makes you punch something or run away,” she says, noting that Hawai‘i has juvenile runaway laws that criminalize the behavior. “But if we understand trauma, this is often a response to a traumatic event that instantaneously happens.”

Rather than punishing behavior issues, trauma-informed care views the behavior through the lens of what a person has experienced, and works with them to recover from the trauma and the dysregulation caused by so much stress. Youths, for example, would be allowed to get out their anger in a safe way, talk through their feelings and slowly learn how to control their impulses.

Those strategies are permeating from the therapeutic world into public schools, which are often the front line in mental health care. At Kohala Middle School, behavioral health specialist Lauren Canton says they try to approach behavior challenges through education and counseling.

“If a child gets angry in a classroom and throws a chair, we ask ourselves, ‘What’s the reason that this child threw a chair? Do we need to address their trauma history? Do they need to learn emotion-regulation skills? Do they need an anger-management program?’ ” The goal is to reshape behavior and put students on a healthier path for the long term.

Building Resilience

Winquist’s first job in social services, after earning her master’s degree at the University of Chicago, was at a residential care home outside the city.

“In the mental health world, this is like going to war,” she says. Many of the youths had been kicked out by multiple foster homes and were in the facility of last resort. She loved the work.

“That was probably the most amazing job I’ve ever had,” says Winquist, “because that’s where you believe in resilience. And you learn to find it for kids.”

One of the boys at the facility was 13 when she met him, and large for his age. She says he rarely spoke and that he carried the emotional scars of a horrific childhood. “But he had these moments when you realized that he just wanted to be a little kid and have fun.”

She slowly got him to play basketball with her, to draw together and build Jenga towers, which is a practice she still uses today with her young clients. Once, he stole a package of M&Ms so he could split them with her.

“He just wanted to connect with a human, and I realized that people’s humanity is really that basic, and resilience starts when you can build a relationship with a person.” That lesson sticks with her as she guides young people through tumultuous years in a tumultuous age.

Is It Depression or Just Moodiness?

Everyone experiences ups and downs, but persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness can negatively affect a teen’s life. Here are signs that it might be depression:

-

- Feeling sad, anxious, worthless or empty

- Lack of interest in activities previously enjoyed

- Easily frustrated or angry

- Withdrawn from friends and family

- Grades have dropped

- Eating or sleeping habits have changed

- Fatigue or memory loss

- Thoughts of suicide or self-harm

Source: National Institute of Mental Health, teen depression fact sheet.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach Hawai‘i CARES 988.

But like all the professionals Hawaii Business interviewed, she worries that there aren’t enough clinicians in the Islands. The problem runs deep, from overbooked therapists in private practice, to underpaid and understaffed nonprofits and government agencies, to not enough professors to educate the next generation.

The shortage is worse on the Neighbor Islands, where mental health needs can also be serious. In 2022, Child & Family Service’s crisis mobile outreach team, which makes personal assessments based on calls to a hotline, saw 50% more Hilo youths than the year before, and 33% more in Kona.

Charmaine Higa-McMillan, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist who runs the master’s program in mental health counseling at UH Hilo, says the difficulty finding mental health care can have long-term consequences.

“I’m really worried about the average child who may not have supportive families and may be suffering in silence,” she says. “That, combined with access problems, really concerns me for the future and what it’s going to be like for them as they become young adults.”

Part 2: The Rocky Path to Becoming a Mental Health Provider

College graduates face formidable training requirements and few positions that pay, while experienced providers struggle to keep pace with Hawai‘i’s high cost of living.

When someone asks Charmaine Higa-McMillan, Ph.D., for a recommendation for a therapist, she gives them 10. That’s not so they can vet and choose, but because more possibilities mean a better chance to find someone who is taking new clients.

For one thing, mental health needs far outstrip the supply of providers. Even physicians are scrambling to find them for their patients. Seventy-eight percent of doctors in Hawai‘i say mental health providers are the most-needed specialty, followed by psychiatrists at 73%, according to the 2022 Access to Care report. The shortage is particularly acute on Neighbor Islands.

Another factor driving the shortage is the sheer time and effort involved to become a certified therapist. The most arduous path is to earn a doctoral degree in psychology or go to medical school for psychiatry. Others take the master-degree route in fields such as social work or mental health counseling. From there, it can take years of training under supervision and passing state exams to get licensed.

Higa-McMillan is program director of the graduate counseling psychology program at UH Hilo. The program accepts just 20 master’s students a year, about three-quarters from Hawai‘i. The students are required to live in the Islands but take classes online.

Students pay full tuition – $5,868 per semester for Hawai‘i residents, $13,284 for nonresidents – as the doctoral-level psychology program at UH Mānoa gets the graduate-assistant jobs and tuition waivers, says Higa-McMillan.

Despite that, the UH Hilo program receives lots of applicants and would like to expand to 30 students, says Higa-McMillan, but the department is down by two positions. Like the rest of the university system, hiring requires special permission, and a request is in for funding to fill the jobs and create an additional faculty position.

One of Higa-McMillan’s current students is Christina Swafford, who is finishing the two-year master’s program in clinical mental health counseling. In the practical portion of the program, she was placed in a temporary paid position offering online counseling at the Hawai‘i Center for Children & Families, a group practice in Kapolei.

Swafford loves the job and the young people she counsels, but when she graduates in May she has to leave it behind. With just a master’s degree, this private-practice employer she interned with can’t bill private insurers for reimbursement for her services. Insurers will only pay after Swafford has completed 3,000 hours of supervised professional work and been certified as a licensed mental health counselor. That’s a year and a half of full-time work.

(House Bill 1300, which didn’t pass at this year’s state Legislature, would have allowed insurance reimbursements for mental health services provided by a supervised intern, as well as for people with some provisional licenses.)

Her next job, then, needs to be a nonprofit or public-sector job that doesn’t rely on private-insurance reimbursements to stay afloat. The other alternative is charging out-of-pocket fees, which many people can’t or won’t pay, or paying a provider to supervise her work.

Swafford is stuck in limbo, hoping for one of the few paid positions to complete her 3,000 hours of supervised experience, but knowing that she might have to return to Oregon, where she grew up, or move somewhere else.

Nonprofits Are Underfunded

If she’s lucky, Swafford might land a paid postgraduate position at Child & Family Service, which is near the employer she had as a graduate student. This nonprofit organization in ‘Ewa Beach has been in operation since 1899 and works with vulnerable communities across the Islands.

“(State) funding has been stagnant for years and years … impeding our ability to provide mental health services.”

– Karen Tan, President & CEO, Child & Family Service

Swafford would be thrilled with that. But after completing her lengthy training, she would face the same dilemma that many therapists and teachers and social workers face: low pay, made worse by the exorbitant cost of living and burden of student-loan debt.

Child & Family Service, for example, gets its funding from about 120 state contracts, but the dollar amounts have been flat for ages, says Karen Tan, the nonprofit’s president and CEO. She and about 50 similar organizations have formed a “true cost coalition” that is advocating for more state funding to cover rising expenses, particularly salary boosts.

“Funding has been stagnant for years and years and years, which is impeding our ability to provide mental health services and why people are leaving and why there’s a backlog,” says Tan.

“These are well-educated, highly skilled clinical folks, and we’re paying them what the state contracts allow us to pay them,” she says. “It’s almost like, ‘You chose that career, therefore you must suffer.’ ”

Three of her staff recently announced they’ve accepted federal jobs in Hawai‘i, which Tan says are typically positions with the military.

“So you’re pulling clinicians away from the greater community in Hawai‘i because the federal government actually pays a livable wage,” says Tan. She notes that her top clinical position only recently cleared the six-figure threshold.

While she’s had to cut staffing and reduce services in some areas, she says that “fortunately, we’ve got enough compassionate staff that say they’ll do it even though the salary is so low.”

Swafford could also try to find postgraduate experience with state agencies, such as the Department of Education, the Department of Health or Child Welfare Services. But for many, that turns into a short-term option.

Based on anecdotes from the field, Higa-McMillan thinks that people often jump ship when their training hours are completed and license secured. “Once they get licensed, then they can leave and start billing private insurance to get paid a higher rate,” she says.

Reimbursements from the federal Medicaid plan are significantly lower, making it harder to accept many low-income Med-Quest patients in Hawai‘i and harder for patients to find help.

Staffing Problems

At the state Department of Health’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division, Jamie Hernandez Armstrong, Ph.D., the chief psychologist, cites struggles with staffing and finding outside providers. The Department of Health overall had a 24% job vacancy rate as of April.

Armstrong’s division works with youths with severe mental health challenges, including early-onset psychosis. Almost half of her clients are Native Hawaiian.

Her team of about a dozen psychologists and a handful of psychiatrists works at family guidance centers on O‘ahu, Maui, Kaua‘i and Hawai‘i Island, treating young people directly and helping to connect them with the appropriate services.

Some of the providers they contract with include Child & Family Service, Catholic Charities of Hawai‘i, Hale Kipa, Aloha House and the Bobby Benson Center. But outside providers are stretched thin and face staffing problems of their own.

“Prior to the start of the pandemic, we were serving around 2,500 kids at a time, and now we’re serving closer to half those numbers,” says Armstrong. “Part of the struggle is that there’s a lack of mental health providers, and sometimes kids are waiting for a long time.”

Another reason she thinks her division can’t find outside providers is that many are leaving intensive, in-person therapeutic environments for telehealth. Telehealth, she says, doesn’t work for her clients, who, at the lowest level of care, see a therapist for multiple hours a week in their homes.

Tan confirms that, as a licensed clinical social worker, she receives a barrage of telehealth offers. “I get emails all the time saying, ‘Come work for us. You’ll make $110,000 a year doing online counseling.’ I can imagine someone saying, ‘I think I’m going to go do that.’ ”

Other providers stay in their state positions but take second jobs to make ends meet. “I know a lot of clinicians who work for the government and they also work in private practice, which is just wild to me,” says Swafford. “For many people going into the field, the plan was to have just one career.”

At Kaiser Permanente’s Waipi‘o clinic on O‘ahu, Andrea Kumura, a licensed clinical social worker who works primarily with children and teens, says her clinic has been short-staffed for a decade, even as demand for services has spiked. When kids returned to school, it triggered a wave of social anxiety and academic stress after so many months online, she says.

Kumura has 85 clients and sees 27 of them each week. It takes two to three months to schedule an initial appointment, and follow-up appointments take six to eight weeks to schedule. For regular patients who need twice-monthly visits, appointments have to be made two months in advance.

“It’s nearly impossible for teens to get weekly appointments, which is the frequency that many need,” she says.

Kumura was on the picket line during a 172-day strike that ended in February, which is considered the longest work stoppage of mental health care workers in U.S. history. She’s glad to see many of her patients again, and happy that more employees are being hired.

But she says Kaiser is still filling the vacant positions of people who left permanently, and her caseload would need to be halved to give young people the attention they need.

Prioritizing Mental Health

Hawai‘i’s priorities are often misplaced, says Tan, and the worsening state of mental health among its young people is a testament to that.

“I’m a firm believer that where you spend your money is where your value is,” she says.

With years of experience in social services, she views many mental health issues as byproducts of poverty and family struggles. Communities in distress create young people in distress, she says.

Tan wants to see more investment in preventive “upstream” services before crises erupt, and higher pay so that the field attracts and retains the best people. And given the huge number of young people who struggle with anxiety, depression and suicide ideation, the usual excuses fall flat.

“Someone will always say, ‘There’s so many demanding needs,’ ” says Tan. “Well, tell me one person whose child is suicidal who would say, ‘Go fill that pothole. That’s much more important than my youth.’ ”