How Teachers from the Philippines Help Students in Hawai‘i

Eighty teachers arrived last year to fill recurring vacancies in rural public schools. Here’s what some of them say about their first year in Hawai‘i.

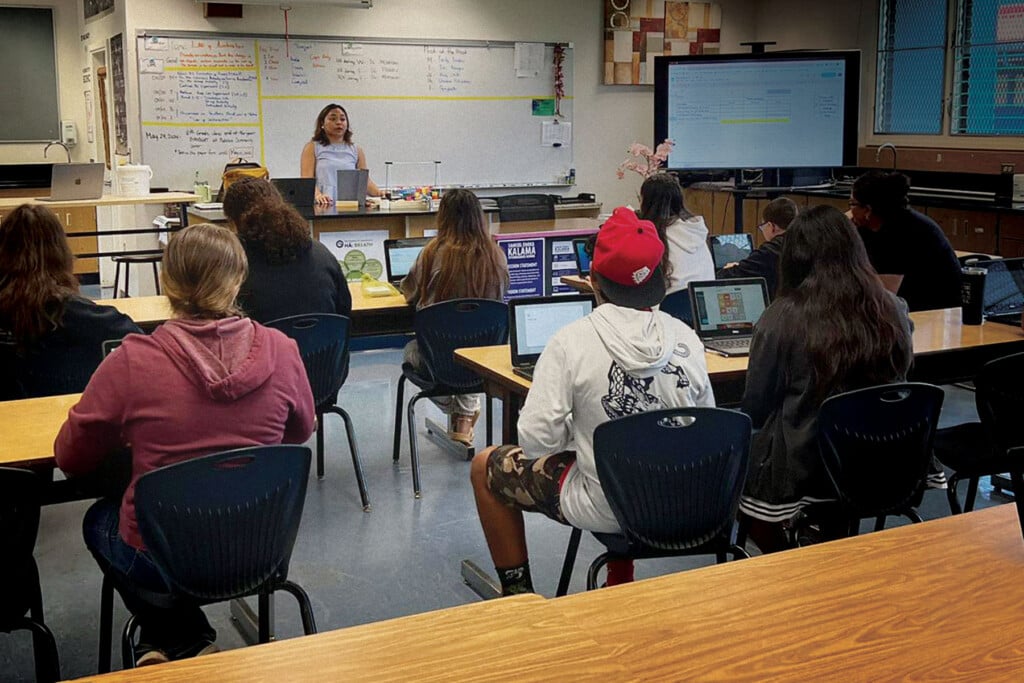

Natasha Ubas had been a teacher in the Philippines for nine years and had never been abroad until last year, when she began teaching math and science at Samuel E. Kalama Intermediate School in Makawao, Maui. Almost immediately, her students questioned her capabilities.

“My kids were literally telling me, ‘What the heck are you doing? You don’t know what you’re doing.’” Ubas recounts. Now, the students feel she does a good job. She adds that a lot of the students asked her if they could visit her next school year, even though they don’t have a class with her.

She says teaching styles in the Philippines and Hawai‘i differ, so early on in her work on Maui she would ask her students how they learn best. And Ubas says she tries to connect personally with students and learn about Hawai‘i’s culture.

The wildfires in Lahaina and Kula in August 2023 were traumatic and frightening for her and the students, she says, but experiencing the island’s aloha spirit through it all “was amazing.”

Ubas was one of 80 teachers who came to Hawai‘i last summer under J-1 visas issued by the federal government for work-based and study-based programs. The teachers are sponsored by the state Department of Education and can stay in the U.S. for up to five years.

The DOE program started in 2019 with 10 teachers from the Philippines. This summer, 50 teachers are scheduled to arrive and begin teaching in public schools.

It’s a good match, Ubas says. “Our group is very lucky that we’re in Hawai‘i because of the fact that the culture here is very rich, and it closely resembles the Philippine culture.”

Hawai‘i suffers every year from a shortage of qualified teachers, with vacancies especially hard to fill at rural schools. These teachers from the Philippines help fill the gap.

Similar Education Systems

The J-1 program is a “cultural exchange” for teachers. They share insights about their home culture while learning about Hawai‘i’s culture, says James Urbaniak, the DOE’s lead recruiter.

He says the DOE currently recruits exclusively from the Philippines but can recruit from other places.

The state targets the Philippines because the education system there is “quite similar” to the system in Hawai‘i, particularly in the way the two systems developed, Urbaniak says, and because of the large Filipino population in the Islands.

Urbaniak says Filipinos make up 30% of the student population in Hawai‘i’s public schools but less than 10% of the educators. Urbaniak says the incoming teachers will also help fill vacancies “in areas of need,” such as rural communities across the state.

Competitive Process

Acceptance into the J-1 program is “very competitive” and many of the teachers from the Philippines have advanced degrees, Urbaniak says.

“Our candidates are fluent, not just in English, but they’re multilingual in a variety of languages.”

Applicants must have a college degree and at least two years of professional teaching experience, although “the vast majority have upward of seven to 30 years,” Urbaniak says. He adds that the Philippines has programs that are equivalent to degrees in the U.S. and that most teachers that apply for the program have a master degree or doctorate.

The DOE gives each teacher a $3,000 bonus to off set housing costs in Hawai‘i, according to Urbaniak. Teachers get paid the same as other DOE teachers with similar credentials. He says the J-1 program also helps teachers with housing, and that many of the teachers live with each other or with friends or relatives.

Hawai‘i is not the only American destination for foreign teachers. A report by the U.S. State Department says 4,271 foreign teachers were employed in U.S. school districts in 2021 – up 69% from 2015.

A Cultural Exchange

Jerico Jaramillo, another teacher who arrived from the Philippines last summer, works at Lāna‘i High and Elementary School.

It’s Jaramillo’s first time in Hawai‘i. Initially, he envisioned Hawai‘i and the U.S. to be a place where he could see “tall buildings and skyscrapers.” But he found Lāna‘i to be “just like the Philippines.”

Jaramillo applied for the J-1 program because he wants to learn new things and bring that knowledge back to Philippine classrooms.

Jerico Jaramillo, who came from the Philippines last summer, teaches at Lāna‘i High and Elementary School. The program that brought him to Hawai‘i encourages cultural exchange, so he taught his class to do the “tinkling,” a traditional Filipino dance with bamboo sticks. | Photo: courtesy of Jerico Jaramillo

“I want to do some meaningful contribution to our educational system. Although we have a nice one, we can still improve it,” he says.

One requirement of the J-1 program is cultural exchange, which the teachers fulfill by holding events and demonstrations that showcase Filipino culture. For example, Jaramillo taught his senior class how to do the “tinikling,” a traditional Filipino dance with bamboo sticks.

That benefits the many Filipino students in the public schools who want to connect with their roots, Urbaniak says.

“There’s so much educational research that shows … that all students benefit from diverse educators,” says Urbaniak. “That’s especially true for our Filipino students who can see an educator in front of them who reminds them of their family, their culture.”