Private Equity Owns a Big Chunk of Hawai‘i’s Hotels. Here’s Why That Matters.

Private equity companies own almost 30% of Hawai‘i’s hotel rooms, a huge increase in the past two decades. We investigate the pros and cons.

Illustration: Kalany Omengkar

It’s common for major Hawai‘i hotel transactions to make headlines. Among them was the $1.1 billion purchase of the Grand Wailea and the $275 million purchase of the Ritz-Carlton Kapalua in 2018. In 2019, the Holiday Inn Express Waikiki went for $205 million; two years later, the Royal Lahaina Resort was sold for $430 million and the Sheraton Kona Resort & Spa at Keauhou Bay for $90 million.

Each was acquired by a private equity firm, a type of investment company known for using lots of debt to buy companies and then doing quick flips designed to maximize profit. While private equity investments can help their acquired companies access needed capital and innovate, they’ve also caused devastating social impacts.

KKR and other firms drove Toys R Us into bankruptcy and laid off 30,000 workers, initially without severance pay. KKR has also come under fire for patient abuse, neglect and deaths that occurred at group home operator BrightSpring Health Services, spurring an investigation by four U.S. senators. The United Nations accused Blackstone, one of the world’s largest corporate residential landlords, of contributing to the global housing crisis for undertaking aggressive evictions, pushing out low- and middle-income tenants, inflating rents and imposing an array of fees.

Private equity firms manage about $12 trillion in U.S. assets and currently invest in 14,300 companies, according to Morningstar, a financial services and research firm. Private equity’s harmful impacts have been so dire in some cases that U.S. lawmakers in recent years introduced legislation to force them to take responsibility for the outcomes of the companies they acquire and tax institutional investments in single-family housing to discourage such purchases. President Joe Biden’s administration is also imposing a rule to require nursing homes that accept Medicare or Medicaid to disclose their owners.

Despite this national controversy, the large stake that private equity holds in Hawai‘i’s tourism industry has largely gone unnoticed. An analysis by Hawaii Business Magazine shows that two dozen private equity firms own 33 of the state’s 144 hotels – controlling nearly 30% of all rooms – raising questions about whether some larger impacts of Wall Street control could be felt here. And West Maui, which was devastated by the August Lahaina wildfire, has the highest concentration of these owners: five of the 11 hotels are owned by private equity. In 2003, private equity owned 4% of the state’s hotels.

The 33 properties include hotels that private equity owns directly, through local subsidiaries or as part of ownership groups. And the count includes one 18-room Lahaina property that was destroyed in the fire but excludes military hotels, timeshares and condo-hotel properties, which have different ownership structures.

Community activists and others say that the increasing presence of Wall Street investors in Hawai‘i is one example of how the hotel industry is increasingly being run by real estate corporations more interested in their bottom lines than in providing excellent guest service or in the long-term impacts on local communities.

“It seems more and more the concentration of wealth and power are in the hands of the few, and it looks like the trend for hotels, resorts, short-term rentals – so all the tourism-related lodging,” says Keani Rawlins-Fernandez, a Maui County Council member.

Maui’s nine private equity-owned properties control half of the island’s hotel rooms. Rawlins-Fernandez worries what will happen if more hotels are owned by private equity firms that maximize shareholder profit at the expense of their employees and the environment: “I’m very concerned about the health and well-being of Hawai‘i and Maui.”

Local hotel consultants and private equity owners say these private equity firms are responsible for major property improvements. Keith Vieira, principal of KV & Associates Hospitality Consulting, says those improvements have helped bring in higher spending visitors and that their investments in hotel upgrades are a large reason why Hawai‘i, before the Lahaina fire, was expected to generate nearly $1 billion during 2023 in transient accommodations tax revenues, the so-called hotel room tax.

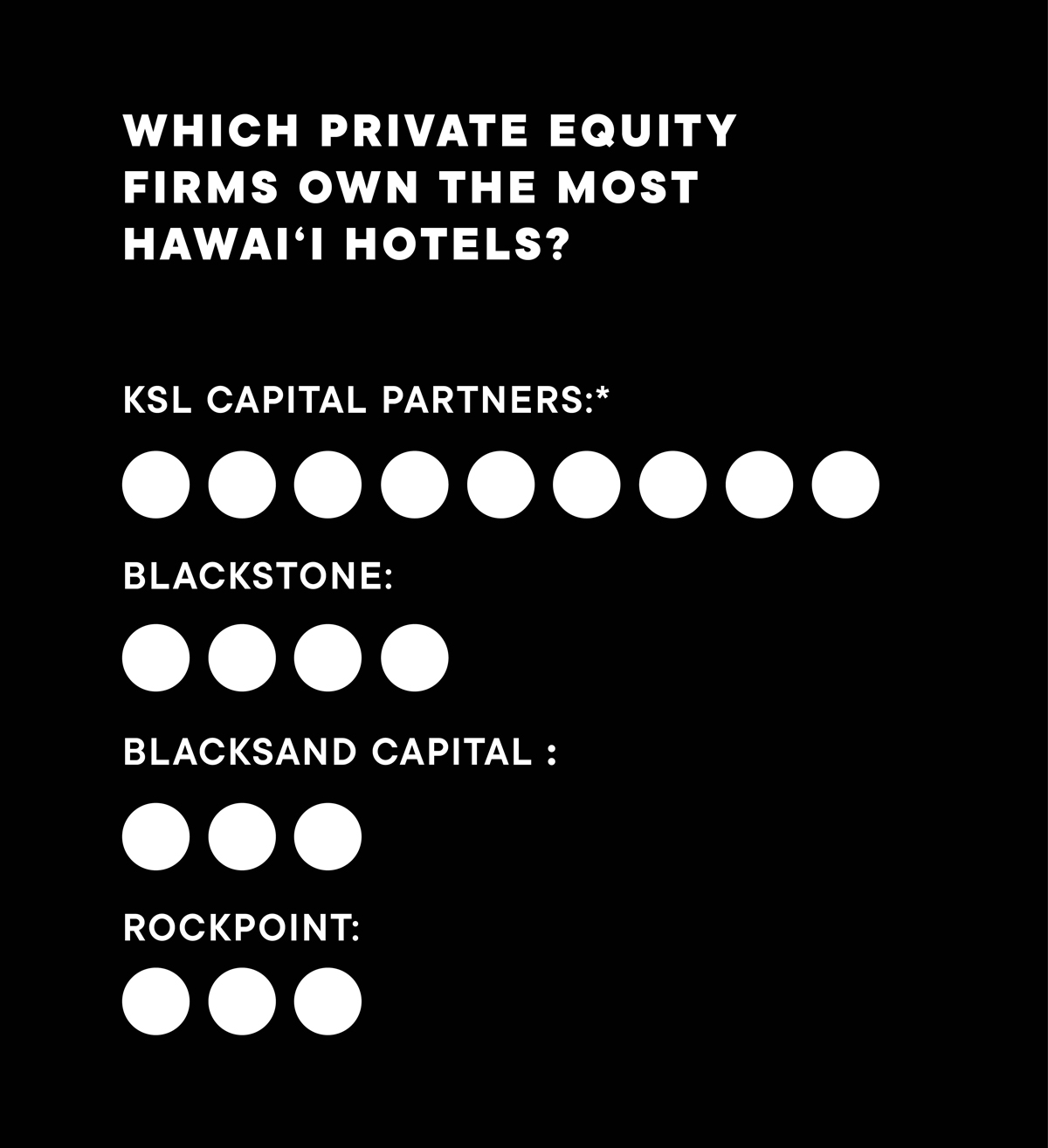

He says that private equity is sometimes criticized because most firms are not based in Hawai‘i. Denver-based KSL Capital Partners, which manages $21 billion of assets, owns the Sheraton Kauai Coconut Beach Resort and, through its ownership of Outrigger Resorts & Hotels, eight properties. Blackstone, which manages $1 trillion of assets worldwide from its New York City headquarters, owns the Turtle Bay Resort, Grand Wailea, Ritz-Carlton Maui and King Kamehameha’s Kona Beach Hotel.

“It’s been better for us because they’re putting so much investment into these resorts,” he says. “But that’s not recognized.”

Corporate Investors

Private equity firms invest by assembling large pools of money from insurance companies, endowments, foundations, pension funds, family offices and wealthy individuals. These funds typically have 10-year lifespans. The firms use that time to create funds and raise money for them, and to then buy and manage their investments before finally selling them. Though a private equity firm generally puts in only about 1% to 2% of a fund’s capital, it makes all the decisions regarding acquisitions, use of debt and portfolio management.

Illustration: Kalany Omengkar

The goal of private equity firms is to overhaul the companies they invest in to increase their value and then sell them for a profit. They do that by finding costs to cut, increasing the efficiencies of operations, and making physical improvements to their assets. They also take out loans through their acquired companies to pay dividends to themselves and their investors. Their companies, not the private equity firms, are on the hook for those loans. For hotel acquisitions, private equity firms tend to use about 50% to 65% debt, according to local consultants and owners. That’s about the same for other types of hotel buyers.

Private equity also makes money by charging performance fees, typically 20% of their funds’ profits. That financial structure encourages them to aggressively pursue profits and shareholder value, though they also make money even if the acquired companies suffer losses. That’s done through annual management fees charged to their investors, which is usually 2% of a fund’s committed capital.

Jeff Hooke is the author of the 2021 book “The Myth of Private Equity: An Inside Look at Wall Street’s Transformative Investments” and a senior lecturer at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. He says private equity firms largely operate in the shadows thanks to minimal disclosure requirements imposed on them by state and federal governments.

“There’s no sheriff in town, there’s no pullup cop on the beat, as far as private equity goes,” he says. “It’s the Wild West.”

A few private equity companies, like Blackstone, KKR and Apollo Global Management, are publicly traded and subject to Securities and Exchange Commission regulations. But for the most part, the minimal disclosures often make it difficult to determine whether a company or property is owned by private equity. For this report, determining the ownership of Hawai‘i hotels often involved digging through layers of shell companies; those layers sometimes obscured the full ownership of the properties.

Unite Here Local 5, which represents about 7,000 Hawai‘i hotel workers, had been tracking private equity hotel ownership and shared its findings with Hawaii Business Magazine. I also searched news articles, company websites, business filings, property tax records, Bureau of Conveyances records, the Hawai‘i Information Service’s tax map key database, and PitchBook, a capital markets research company. These searches may not have captured all private equity-owned hotels.

Hawaii Business Magazine’s goal was to determine the extent of private equity’s presence in Hawai‘i’s hotel industry and how that presence has impacted their employees and the surrounding communities.

Ian and Shay Chan Hodges are community organizers on Maui who have worked for over 20 years to integrate environmental care, social responsibility and good governance into investment policies and practices. They say more awareness is needed about private equity’s presence in the Islands.

“There’s this huge sort of hole in our information about people who are coming in here and understanding, you know, what their motivations are,” Shay Chan Hodges says. Her and her husband’s concern is that private equity’s profits will always take precedence over impacts to local workers and communities.

Nationally, private equity-owned businesses employ about 12 million people, according to the American Investment Council. Justin Flores, director of labor and jobs at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, says that number has grown from about 8 million a decade ago, and many of those workers do not know they’re working for private equity-owned companies. PESP is a nonprofit financial watchdog organization that researches and reports on private equity investments and their impacts.

“Private equity claims that their model is to buy low, make improvements in operations and then have a more valuable asset at the end of their ownership period,” says Alyssa Giachino, director of investment engagement at PESP. “They don’t always achieve that. Sometimes they degrade the quality of the asset because of their thirst for quick profits.”

She adds: “But that doesn’t mean there aren’t examples … where they may have invested into property improvements that would allow them to charge higher rates, and that helps stabilize the cash flow for them, so they do end up with a more valuable asset. Investing in the workforce is another way to accomplish that benefit.” Giachino previously researched private equity and helped organize hotel workers when she worked for the Unite Here union on the mainland.

The 33 properties include hotels that private equity owns directly, through local subsidiaries or as part of ownership groups. These numbers are only for properties classified as hotels in the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority’s 2022 Visitor Plant Inventory. While some hotel properties may have timeshare, condo-hotel or vacation rental units, only their hotel units are included in our count. In some cases, Hawaii Business Magazine updated the number of hotel units and added properties that were not in the 2022 inventory. I did not include military hotels, timeshare properties or condo-hotels in my research, though this list does include four Lahaina properties that were damaged in the August wildfire.

Multi-Decade Presence

Big private equity firms based outside Hawai‘i have owned local hotels since the 1990s. They entered the local market as Japanese companies sold their investments, says Kevin Aucello, principal of Powell & Aucello, a hospitality real estate consulting and brokerage firm.

One early player was Colony Capital, which acquired what’s now the Hilton Waikoloa Village in 1993 with Hong Kong-based PanGlobal Partners and Hilton Hotels. In 1998, Oaktree Capital Management acquired an interest in Turtle Bay Resort, local firm Trinity Investments acquired majority ownership of what’s now the Fairmont Kea Lani with Apollo Group and the Goldman Sachs Whitehall Fund, and KSL Recreation Corp., a subsidiary of KKR, acquired the Grand Wailea. KKR is famous for popularizing the leveraged buyout model in the 1970s and 1980s, and KSL Capital Partners grew out of KSL Recreation Corp.

Under Oaktree, Turtle Bay Resort faced labor disputes, and community opposition when it wanted to build 3,500 additional hotel and residential units. The property was deeded to a consortium of investment firms to avert foreclosure. At the time, it was one of more than a dozen hotels in distress, according to a 2011 Hawaii Business Magazine article.

Various private equity firms have come and gone in the decades since. Sometimes, private equity acquires foreclosed or distressed hotels. That’s what happened to the now-demolished Mākena Beach & Golf Resort and former Sheraton Kona Resort & Spa Keauhou Bay, now an Outrigger resort. But, often, it just depends on the market and what’s available.

Honolulu’s Kobayashi family has been investing in hotels for over 20 years. In 2009, BlackSand Capital was created to do that work on behalf of the family and other investors in the form of a private equity fund, says BJ Kobayashi, chairman and CEO of BlackSand Capital. And 80% of its investors are based in Hawai‘i.

“I really do think it makes a difference that if we make a dollar, if 80 cents stay in Hawai‘i, that’s just different than if you have a company that’s private equity that the investors are outside of Hawai‘i,” he says.

It currently co-owns the Royal Lahaina Resort and Twin Fin with Rockpoint, a Boston private equity firm with $14 billion in assets under management, and Highgate, a hospitality management and investment company. BlackSand also co-owns the Kaimana Beach Hotel with Tsukada Global Holdings, a public company in Japan. BlackSand says it looks for hotels with good locations in submarkets with high barriers to entry. It also looks for hotels to which it can add value.

Trinity Investments, another locally based private equity company, takes a similar approach. It has owned, often with mainland private equity firms, the Ritz-Carlton Kapalua, Kahala Hotel and Mākena Beach & Golf Resort. It currently co-owns the Westin Maui Resort & Spa in Kā‘anapali with Oaktree, a firm with $183 billion in assets under management. Greg Dickhens, Trinity’s principal and managing partner, says the firm tends to reposition its hotels as more upscale destinations through physical improvements to the property, bringing in top-tier management and, sometimes, rebranding. Trinity also invests in hotels in the U.S., Mexico and Europe and manages about $5 billion or $6 billion in assets, Dickhens says.

In some cases, mainland-based private equity giants have gained control of hotels through the local companies that run them. Cerberus Capital Management, for example, had ownership stakes in the Japan-based parent companies of Honolulu’s Kyo-ya Hotels & Resorts and Prince Hotels & Resorts from the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s. In Hawai‘i, the two local hotel companies once owned eight hotels on three islands.

Blackstone owned or managed a handful of Hawai‘i Hilton hotels when it owned the Hilton Hotels Corporation from 2007 to 2018. In 2016, Denver’s KSL Capital Partners acquired Outrigger Resorts & Hotels, which operated, owned or managed 37 hotels in Hawai‘i, Guam, Fiji, Thailand, Mauritius and the Maldives. Outrigger had been owned and operated by the Kelley family since 1947. According to PitchBook, KSL is the most active private equity hotel investor in the U.S.; in the last five years, it made 26 investments.

Hawai‘i continues to be attractive for private equity buyers because it’s one of the highest performing hotel markets in the country, says Tim Powell, principal of Powell & Aucello. A big allure: It’s unlikely that new hotels – and thus new competition – will be built due to strict zoning regulations.

Ben Rafter, a hotel owner and president and CEO of hotel operator Springboard Hospitality, says that many of the large private equity firms are looking to write checks for $100 million or more to buy properties, and Hawai‘i is one of the few markets where they can do that.

In the last two years, Outrigger acquired four properties in Hawai‘i and four in Thailand and the Maldives. Those include the 18-room Plantation Inn that was destroyed in the Lahaina fire and the 350-room condo-hotel Kaua‘i Beach Resort & Spa. An Outrigger spokeswoman says Outrigger manages the Kaua‘i Beach Resort as a traditional hotel and owns most of the units, but she could not provide specifics on unit counts. David Carey, the longtime CEO of Outrigger until its sale by the Kelley family, says that thanks to KSL’s ownership, Hawai‘i-based Outrigger is expanding in the way he always dreamed.

“When we were buying and selling hotels, the average price of those hotels were somewhere between $25 (million) and $125 million a property,” he says. “Now, if you look at hotel prices, it starts $200 million and up, $200 million, $400 million. So that’s more capital than a small family business could put in.”

Hotels Become More Upscale

In 2021, the Westin Maui Resort & Spa debuted the jewel of its three-year, $120 million property-wide transformation: its 217-room Hōkūpa‘a tower, named for the North Star.

It’s the first and only hotel-within-a-hotel concept in Kā‘anapali, says GM Josh Hargrove. The rooms have wood floors and modern furniture and designs that evoke the sand and sea of Kā‘anapali Beach. Guests who stay there have perks that other hotel guests don’t, like access to the tower’s second-floor club, The Lānai at Hōkūpa‘a, where they can swim in an infinity edge pool, enjoy cocktails made by a certified mixologist and attend exclusive Hawaiian cultural activities.

Hargrove says the Westin increased its Hōkūpa‘a tower nightly rates by about 80% after it was renovated. That attracts visitors with more money to spend in the surrounding community and leads to higher employment levels due to the elite service required.

“All the other businesses that come after and then rely on tourism thrive when you have an increase in customer or visitor spend and discretionary income,” he says. “It’s not only the renovations. All of the aftermath of that just lasts for years or decades, as we make sure this world-class destination competes with the best of the best all around the world.”

The Westin Maui, which was built in 1971, is undergoing a $30 million renovation, expected to be complete in early 2024. That project includes a transformation of its Ocean Tower rooms and the creation of a social entertainment space with Topgolf swing suites, bowling, virtual reality games and a bar.

Hawai‘i hotels have completed more than $2 billion in improvements since 2019, Vieira says. Significant investments like that are needed if hotels here are to compete on a global luxury level, he says.

“Why private equity has been so good for Hawai‘i is when they come in and buy something, they don’t plan to sit on it for seven years and then sell it with maybe more profit,” he says. “They go in and they go, ‘What can be done to reposition and rebrand, upgrade, create a luxury tower?’ Then in generally seven or eight years, they’ll sell it to the next private equity firm, which will do the same thing. What this has done for Hawai‘i is it has created significant investments.”

Dickhens was the president of Kyo-ya Hotels & Resorts during the Cerberus era. He says Kyo-ya invested over $350 million to reposition its Sheraton Waikīkī, Moana Surfrider and Royal Hawaiian properties, which hadn’t seen significant capital investments in a while. The Prince Waikiki also completed major upgrades in 2017, just as Cerberus fully exited from Seibu Holdings. Dickhens was VP of Prince Resorts from 2014 to 2016.

Outrigger Resorts & Hotels has made major reinvestments, too, in the years since it was acquired by private equity company KSL. Jeff Wagoner, president and CEO of the Honolulu-based company, says the company has infused over $300 million into its properties.

That includes an $80 million renovation at the Outrigger Reef Waikīkī Beach Resort. The project paid tribute to the area’s voyaging past and included transformed guest rooms, the Kani Ka Pila Grille and open-air Herb Kāne Lounge. It also created a permanent Hawaiian cultural center. Kaipo Ho, Outrigger Hospitality Group’s former director of cultural experiences, says the Reef’s renovations showcase a huge leap in Outrigger’s longstanding commitment to Hawaiian culture. He helped Outrigger create its values-based corporate culture in the ‘90s and assisted employees through the transition to KSL. He retired in 2020 after 27 years with the company.

Illustration: Kalany Omengkar

Renovations of the Outrigger Kona Resort & Spa and ‘Ohana Waikīkī East are expected to be complete in 2024. And the newly acquired Kā‘anapali and Kaua‘i resort properties will undergo complete renovations in the coming years, Wagoner says.

The Grand Wailea already unveiled new dining concepts and its updated exclusive Napua tower. Kalei ʻUwēkoʻolani, cultural programming manager and leadership educator, says the resort’s new Kilolani Spa, which will open in 2024, will offer signature treatments and programming inspired by the Hawaiian lunar calendar and traditional Hawaiian wellness practices. And the Humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa restaurant will also incorporate culture into the dishes, such as through ingredients, the way they’re served or how they look.

The resort wants to add 151 new guest rooms and make other enhancements, too, but those efforts are still in limbo as the project goes through a contested case hearing at the Maui Planning Commission.

Several of the private equity owners used loans to fund their renovations. For example, BlackSand Capital took out a $240 million loan when it acquired the 27-acre, 500-room Royal Lahaina Resort, which was not touched by the fire. Some of that loan is being used for a “much-needed” renovation of the lobby, retail, and food and beverage areas, along with upgrades to the resort’s 122 villas, Kobayashi says.

Powell and Aucello say that it’s more common for an existing hotel owner to pay for renovations using funds from their replacement reserves, rather than get another loan. Other times, an owner will refinance their property and do a renovation as part of that process.

Bottom-Line Focus

Located on 40 acres in South Maui, the Grand Wailea was built in 1991. Developer Takeshi Sekiguchi spent $600 million on the 787-room hotel, which included $30 million worth of fine artwork, an entry waterfall, expansive gardens and a 2,000-foot-long pool with slides and rapids.

Listen to the Discussion

On Jan. 18, 2024, our panelists discussed local hotel ownership trends, the investments that private equity firms have made locally, and the impacts on local workers and communities.

Panelists included Cade Watanabe, Financial Secretary-Treasurer, Unite Here Local 5; Ian Chan Hodges, Managing Member, Responsible Markets LLC; Keith Vieira, Principal, KV & Associates Hospitality Consulting, LLC; and Ken Cruse, Founder & CEO, Soul Community Planet (SCP) Hotels.

In 1998, the hotel underwent financial restructuring and was sold to an affiliate of investment company Credit Suisse First Boston. Five months later, it was picked up by KSL Recreation Corp.

Former state Rep. Tina Wildberger worked there in the late ’90s in food and beverage. She says under Sekiguchi, taking care of guests and employees was emphasized. But under KSL, the focus shifted to numbers.

“KSL came in hard and started threatening people” who weren’t working the number of hours that it expected them to, she says. “I’ll never forget the number 1,560. They came in and were threatening if you don’t have 1,560 hours in annual that you worked, you’re getting your benefits dropped, your job is in jeopardy.”

Others also describe how things changed at hotels where they worked after private equity took ownership. On a Friday afternoon, Renee Minshall, a worker at the Hilton Hawaiian Village, proudly says she worked at the property when it was owned by the Hilton Hotel Corp. She says those were the “good old days” and fondly describes seeing guests’ babies grow up and get married as families returned again and again.

“We were empowered to go above and beyond for our guests, and do whatever it took to make them happy,” she says. “And we kind of don’t really have that anymore. It’s been lost in the shuffle of all the changes and cutbacks and stuff.”

The changes began after Blackstone acquired Hilton for $26 billion in 2007, Minshall says. Shortly after, a company came in to monitor and evaluate employees’ movements. She later learned they were trying to identify redundancies, and if employees had too much downtime because of the redundancies. She vividly remembers, with tears in her eyes, HR telling her that her position was cut. She ended up interviewing at other companies, but because she was already older, she says, no one wanted to hire her. The union was eventually able to restore her job. When she lost her job, Minshall had just returned to the property after a handful of years living on another island. Before that move, she had worked at the Hilton Hawaiian Village for 12 years.

“It still bothers me until this day that that happened to me,” she says. “You know, and all the years of service I put in, and that’s how they treated me. And they had like, no value for me even though I valued everything I did every day.”

She now works in the bell department, which helps guests with luggage and provides other services, and has moved up in seniority, but she worries that a layoff could happen again. And others in her department are now suffering the ramifications of owners focusing on profits over people and guest service, she says.

The Hilton Hawaiian Village is currently owned by Park Hotels & Resorts, a public lodging real estate investment trust, or REIT, spun out from Hilton Worldwide Holdings. REITs, like private equity firms, aim to generate income for investors but are different in that they must pay at least 90% of their taxable incomes in the form of shareholder dividends each year and are open to individual investors, rather than only institutions or accredited investors. About 7% of Hawai‘i’s hotels are owned by REITs.

Minshall says the number of workers in her department is down 40% since Covid. The property sometimes sees 800 to 900 check-ins a day, so her team is constantly moving across the 22-acre property. When we spoke in early December, her team, made up entirely of full-timers, was struggling with shifts being cut from eight hours a day to five or even four. Employees must work 20 hours a week to maintain their health benefits, so they were barely making the cut some weeks.

Current and former workers at the Turtle Bay Resort and Grand Wailea, owned by Blackstone since 2017 and 2018, respectively, say they’ve been doing more work with fewer staff members. The employees I spoke with – all but one had 10 or more years with their hotels – asked that the magazine not use their names. Some of those who still work at the hotels feared retaliation; others who’ve moved on to new jobs didn’t want to risk their relationships with their new employers.

Some of the Grand Wailea workers say they’re so overwhelmed with their workloads that it’s impacting the cleanliness of the hotel and the speed with which they can respond to guests’ requests. It’s also taking tolls on them physically. One says she has back pain and has hurt herself from having to work fast enough to keep up with everything that needs to be done.

Illustration: Kalany Omengkar

In other cases, some with lower seniority aren’t getting enough hours to maintain their health insurance. One worker says he got so few shifts that he didn’t make enough hours to keep on as a full-timer and lost his health insurance. He’s since had to stretch his medications to compensate.

“I’m totally understanding this is about making money,” he says. “But you cannot mistreat people that you used to make that money. To me, they look at us as just not human beings.”

Workers at both the Grand Wailea and Turtle Bay say they love their jobs but it feels like they’re being pushed out, particularly longtime employees who know the properties and cultures best. And, like the Hilton Hawaiian Village worker, they say the tools they need to express Hawai‘i’s aloha spirit to customers have been taken away, along with the time it takes to do that.

“I think my whole takeaway from this whole thing is what’s sad about Turtle Bay is that it’s not like how it was before,” says a former worker. “Like it really isn’t. The Turtle Bay when I first started, I loved. Everything was about guest experience. Now it’s not.”

That worker adds that returning guests told her that they felt the resort’s aloha spirit felt forced and that everything was about money.

The Grand Wailea, one of Maui’s largest private employers, is part of a class action lawsuit filed by nonunionized spa workers who allege that hotel operator Waldorf Astoria and owner Blackstone “willfully” misclassified them as independent contractors to avoid pay and benefits. There were 115 named plaintiffs as of mid-December, according to Brittany Harmssen, lead-counsel for the plaintiffs.

She says the median tenure of the plaintiffs is 15 years, though many have been with the property since its original owner, which “speaks to their vulnerability and the ability of the hotel to exploit them, essentially.” She adds that many plaintiffs have told her that the resort’s original owner provided some of the best working conditions and that conditions have worsened since.

And some of the issues they faced seemed to originate under Blackstone, she says. For example, spa workers haven’t received their full tips because the hotel takes a percentage of the mandatory 20% gratuity charged to spa clients. They also have also not been paid for providing free services, at the direction of the hotel, to hotel employees and VIP clients. According to Hawai‘i U.S. District Court records, the court cancelled a settlement conference that was scheduled for early December.

A spokesperson for the Grand Wailea wrote in an emailed statement: “While we believe this case is without merit, Grand Wailea cares deeply about our workforce and we remain committed to being a best-in-class employer.”

Larger Picture

Eric Gill, the former head of Unite Here Local 5, which represents hospitality and health care workers in Hawai‘i, says the perceived increased focus on profits over operations and employees is a result of more properties being controlled by real estate companies, rather than hoteliers.

Unite Here Local 5 says it has about 1,400 fewer hotel union members now than in 2019. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union says it’s down by about 2,000 hotel members. At the same time, Hawai‘i hotels are charging higher average room rates and dealing with lower average occupancy rates. Up until October, except for August, hotels statewide each month in 2023 had average daily room rates that were 30% to 40% higher than the same time in 2019. Statewide revenue per available room was 20% to 32% higher, according to Hawai‘i Hotel Performance Reports compiled by the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority. Meanwhile, occupancy rates ranged from 72% to 77%. In 2019, occupancy rates ranged from 78% to 85%.

“Our (total) work hours have improved but the total amount of jobs have not returned,” says Cade Watanabe, financial secretary-treasurer of Local 5. “So that means that not only are the owners reaping the huge benefit from a higher room rate, but they’re reaping the benefit from understaffing our jobs.”

Gill says that Hawai‘i needs a tourism industry that its people will support and feel good about. And that can’t happen when there are fewer jobs yet more tourists putting more pressure on local communities, he says. Visitor arrivals are expected to increase to over 10 million after 2024, according to the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism’s third quarter economic outlook.

“We’re getting shortchanged here. And I think (in) the long-term, this is something these corporate entities aren’t going to attend to no matter what they say,” Gill says.

He explains the implicit social contract behind Hawai‘i’s hotel industry: “We gave them our beaches, so they’d provide the jobs. They shouldn’t get to keep the beach and eliminate the jobs, which are the benefit that we get from them operating in our island.”

Illustration: Kalany Omengkar

In an emailed statement, Blackstone wrote that staffing at Turtle Bay Resort has increased by 10% post-Covid and that it anticipates adding new jobs at the Grand Wailea once its spa reopens in 2024.

“Blackstone has invested more than $650 million to ensure our Hawai‘i hotel properties remain iconic destinations and top employers for generations to come, and we are proud that these investments have created more than 1,300 local jobs,” the firm wrote.

“During our ownership, the average compensation for employees across our hotel properties has grown by nearly 25%, we have supported more than 700 local businesses in the past year alone and, together with our portfolio companies, have donated millions of dollars to the community, including $1.5 million in response to the recent devastating Maui wildfires. We look forward to investing in Hawai‘i over the long term and will continue to be a responsible steward of our properties.”

The firm added that the Grand Wailea has donated more than $5 million to nonprofits in the last seven years, and its Turtle Bay Foundation has awarded over $1 million in grants and scholarships since its inception. The Ritz-Carlton, Maui Kapalua, meanwhile, has donated more than $440,000 to nonprofits over the last five years.

Marty Leary, director of research at Unite Here, the parent of Local 5, says private equity hotel owners tend to cut costs when they have trouble exiting investments, but, in general, reducing staffing is not the primary way they try to flip their properties. Instead, their primary strategy is to reposition the hotel with higher room rates and renovations and then try to sell it at the right time in the real estate cycle. Properties that have unionized employees, for example, didn’t see too many impacts on labor costs when private equity firms took advantage of cheap credit after the financial crisis to buy and sell properties.

Maui Impacts

On a weekday afternoon in early November, Hanaka‘ōʻō Beach Park is largely empty, except for the area housing the Kahana, Nāpili and Lahaina canoe clubs.

There, 20 to 30 people gather under a green tent to organize the “Fishing for Housing” protest that began on Nov. 10 at Kā‘anapali Beach. They were prepared to stay as long as it took for the state and county to use their emergency powers to house displaced Lahaina residents, who have been shuffled around various hotels and condos since August.

Kai Nishiki, a West Maui community organizer, walks over to meet me at a picnic table. At the time, she only knew of one property that was going to renew its contract to house displaced residents after November. The Federal Emergency Management Agency reimburses hotels and condos for housing survivors but not at their full rates.

“Hotel ownership is increasingly important because whoever owns a property determines what the goals and priorities are,” Nishiki says. “And most of the time, if you aren’t from here and aren’t living here, the community’s needs aren’t the priority. The bottom line is. And that likely means more extraction and exploitation for the people who are here.”

She says the fact that over 7,000 residents have been moved around and asked to leave so that visitors can return is indicative of that: “That says profits are more important than people.”

Chris West, president of ILWU, says the aftermath of the Maui fires revealed a lot of intent and sincerity on behalf of some of the hotel owners – and lack thereof among others. He says BlackSand Capital, the Honolulu-based co-owner of the Royal Lahaina Resort, was the most helpful to members impacted by the wildfire.

“They helped us the most by far and have been the most willing to take the loss to help local families, and it’s evident,” he says. “There’s a big difference between a locally owned private equity family” and other kinds of owners. He says Blackstone also stood out for the assistance it gave ILWU members.

In an emailed statement, Blackstone wrote that its community commitment is illustrated by the more than $1.5 million in relocation relief, assistance payments and charitable donations that the firm and its portfolio companies provided to support its hotel employees and others impacted by the fire. It also helped provide thousands of meals through its Maui hotels, donated supplies, and provided laundry services and fresh linens to those in need.

“In moments like that I think it’s really, really important to take a step back and realize why we’re all here,” says Kobayashi of BlackSand Capital. “It’s not just to make investments and make money.”

*All but one property are owned by Outrigger, which is owned by KSL Capital Partners. Its properties include the 18−unit Plantation Inn, which was destroyed in the August Lahaina fire, and the 350−unit condo hotel, the Outrigger Kaua‘i Beach Resort and Spa, which it operates as a regular hotel.

Looking Ahead

Aucello and Powell say that the private equity-owned hotels are still seeing positive cash flows even if they’ve exceeded their timelines for exiting their investments. That means that they can refinance their loans and share some of the proceeds with their investors while still owning the hotel. The Westin Maui, for example, refinanced its existing $360 million loan for $515 million; that includes a $145 million cash-out for sponsors, according to CoStar, a commercial real estate analytics company.

They and other experts don’t expect to see a major change in the types of buyers that have been purchasing Hawai‘i hotels over the last five or 10 years: Private equity firms, for the most part, will continue to sell their larger properties to other private equity firms or to REITs.

“You’ve got to be dedicated and want to get into this market,” says Mark D. Bratton, senior VP of Colliers Hawai‘i. “It’s not inexpensive, it’s not for the faint of heart, it’s not fast money. It’s long-term, it’s a very limited supply of what you can get.”

Read More

Here’s How I Identified Hawai‘i’s Private Equity-Owned Hotels

Thanks to a reporting grant, I spent months digging into private equity’s ownership of Hawai‘i’s hotel industry and how that presence has impacted their employees and the surrounding communities.

Dickhens of Trinity Investments says hotel owners in Kā‘anapali and Wailea are generally large institutional investors who hold their properties for a long time, and they’ll continue with that strategy despite the Lahaina fire. He adds that while private equity firms might be required to sell due to the life of their funds, there are ways they can recapitalize and stay in a project under a different ownership form.

Rafter says the market will continue to consolidate. That means investments will continue to get bigger and the pool of investors will continue to shrink. It also means there will be fewer people like him investing in smaller hotels with short ground leases.

Leaders at Unite Here Local 5 and the ILWU say that 2024 will be a big year for hotel contract negotiations. They say they’ll fight to increase worker wages and address increased workloads.

In Southern California, thousands of Unite Here Local 11 hospitality workers have been striking on and off since summer after 60 hotel contracts expired. They’ve been demanding better wages – ones that keep up with the rising cost of living – plus improvements to their health and retirement benefits. As of mid-December, the California union had reached tentative agreements with 10 hotels.

“I’ll be honest, I don’t care who owns it, I just care if you’re paying our workers living wages,” says West of ILWU. “That for me, that’s what it’s more about. …As a whole, the tourism industry has definitely changed and has shifted more towards profit margins than necessarily (visitor) experiences.”

Both Local 5 and ILWU have been able to negotiate with private equity owners. About 40% of the private equity-owned hotels have union employees. The boutique Hyatt Centric Waikiki Beach is owned by KKR, a private equity firm that manages $528 billion in assets, and has been a union property since 2018.

Local 5 recently negotiated a new six-year contract that will bring Hyatt Centric workers’ pay up to the union’s standard, says Anson Leaeno, who has worked at the property since it opened in late 2016. The contract also provided severance pay to food and beverage workers impacted by the property’s restaurant closure. Leaeno says he’s enjoyed working in the hotel’s housekeeping department and is paid well.

Minshall, the Hilton Hawaiian Village worker, says it shouldn’t matter who owns a hotel, but there’s a disconnect between a hotelier, like the old Hilton Hotels Corp., and an investment company.

“They’re only investing for their shareholders and to make money, right? They’re not making us happy,” she says. “They’re making their pockets happy and bigger and bigger and bigger every year. And we know the numbers, right? I’m sharing the numbers of my people now and making them aware of what’s going on. And now they’re aware, now they’re more willing to speak up for their rights. Now? Yeah, because we’re the ones that run the hotel. We’re the ones that work.”

The reporting of this story was supported by the Poynter Institute through a grant from the Omidyar Network. The two organizations had no role in the reporting or editing of this story.

The private equity-owned properties (teal place markers) in this map include hotels that private equity firms own directly, through local subsidiaries or as part of ownership groups.

A Different Private Equity Model

Some local and mainland hotel owners are using private equity to help them obtain and hold properties long-term.

That’s the case with Ken Cruse, the former CEO of Sunstone Hotel Investors, a public real estate investment trust. In 2018, he created Soul Community Planet, a California wellness hospitality brand, whose vision, he says, is to help make the world a kinder, better place. SCP, with an institutional private equity limited partner, owns the 138-room SCP Hilo and four other hotels on the mainland.

He says SCP is a long-term investor that’s more focused on building its brand and operations than generating a high internal rate of return. Since acquiring the former Hilo Seaside Hotel in 2021, he’s brought over SCP’s Every Stay Does Good program. Through the program, each stay at the hotel contributes to organizations helping adolescent mental health, children with life-threatening illnesses and global reforestation. SCP Hilo also created a partnership with the Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund. Through that alliance, each stay at the hotel helps facilitate HWF’s recovery of 2.2 pounds of marine debris from local beaches. Cruse says his focus is to start with what’s best for the community.

“If we don’t have a Hawaiian that can buy this hotel and take this hotel over, this is it (the best alternative) for us,” says Breeani Kobayashi, GM of SCP Hilo. Her grandfather, Richard Kimi, built the hotel in 1956. “I thought to myself this is the type of human that should be buying hotels in Hawai‘i, if at all,” she says of Cruse.

Cruse knows that his goal of holding hotels long-term goes against the private equity model, which typically expects to realize returns in less than a decade. He says he’s dealt with that through liquidity events. These events might include refinancing offers so that investors can receive their cash and exit, or offers to buy out an investor or to consolidate a property’s equity under SCP’s own balance sheet.

“The worst thing that could happen to a hotel is to continually trade it and have like a two-year or three-year cycle where it’s sold, new brand comes in, new management company comes in, new philosophy of how they operate comes in,” he says. “The hotels succeed or fail mostly around the team that’s operating the hotels. If you have a stable, well-trained, capable team that really loves what they’re doing, guest experiences are great.”

Ben Rafter of Springboard Hospitality takes a similar approach. He has owned a handful of smaller hotels with other local and mainland investors. Those investors are a mix of individuals, private equity firms, REITs and family offices. (Family offices are companies that manage assets and investments for wealthy families.)

He says the hotels he targets aren’t typically sought after by institutional firms because they tend to be smaller properties, often with shorter land leases, like the 250-room Ohia Waikiki Studio Suites and the 94-room White Sands Hotel.

“We’re trying to put together groups that can hold for longer periods of time and might be focused on either holding real estate in Hawai‘i or an equity multiple instead of internal rate of return, or just having the flexibility to do what we want over time,” he says.

“If it’s tied into a fund structure, that’s not any better or worse, it just means there’s going to be some restrictions on it. And most of the time, that means within five to seven years, you’re trying to monetize that asset because the fund has invested all of its proceeds, all its funds and is returning proceeds to the investors.”