Caring for the Community

Kaiser Permanente has a hand in helping Hawai‘i in many different ways, from responding to the needs of Maui residents to helping nonprofits care for the land.

Monitoring the Health of Maui

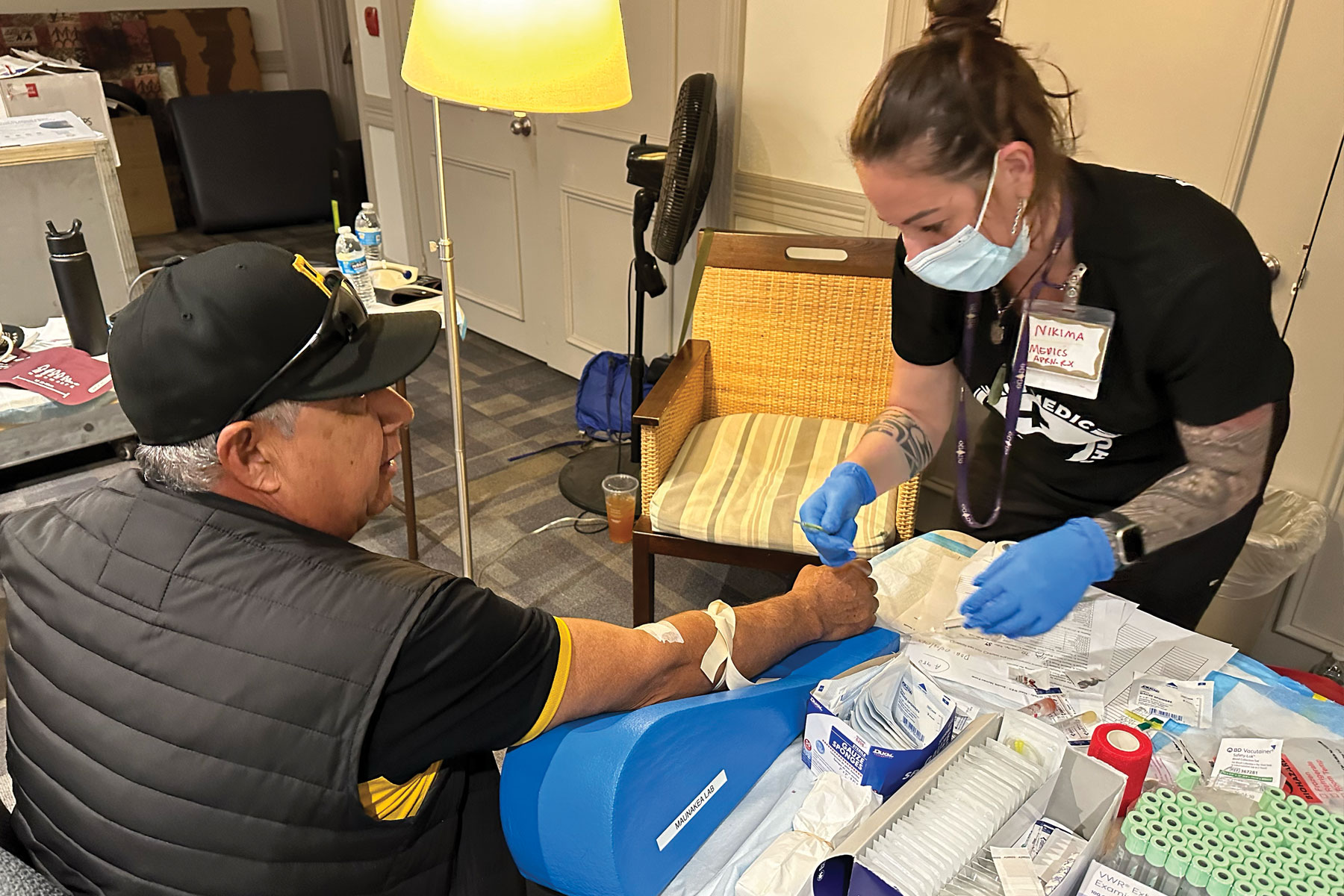

The Maui Wildfire Exposure Study follows the health and recovery of Maui wildfire survivors.

It’s easy to overlook a cough, especially amid competing priorities like finding a job, tending to family, and searching for a home. But for Maui residents affected by August 2023’s wildfires, either directly or indirectly, that cough could be a symptom of deteriorating health.

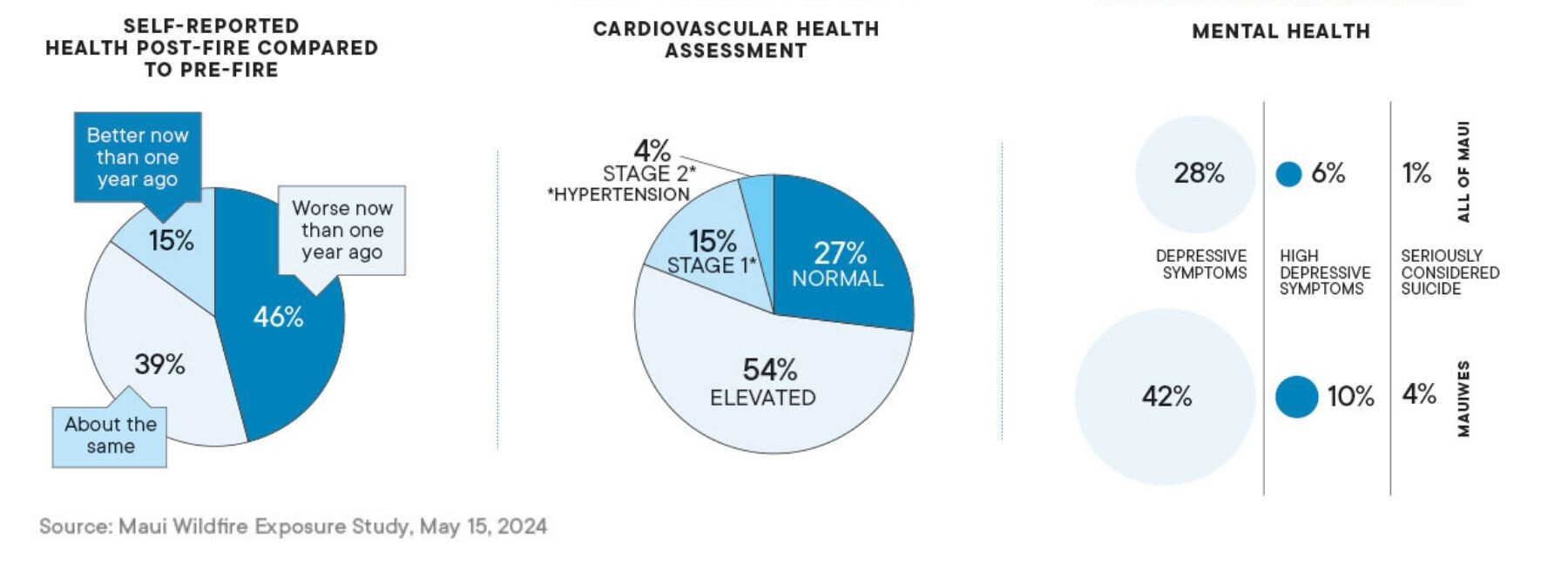

Forty-six percent of Maui residents surveyed reported that their health had declined in the past year, according to initial findings from the Maui Wildfire Exposure Study, or MauiWES. The survey was conducted by researchers at the University of Hawai‘i and funded by the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and Kaiser Permanente. It also reported that up to 60% of participants may suffer from poor respiratory health.

“It’s been really challenging for them to recover, because it’s not just one thing that will solve all of their problems. It’s a myriad of issues that they have to resolve to really not only recover, but to do so in a healthy way,” says Alika Maunakea, a professor at UH Mānoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine, which headed up the study along with the University of Hawai‘i Economic Research Organization, or UHERO.

While the study, consisting of 679 participants, included the collection of biomedical samples, it also looked at social factors such as mental health, depression, suicidal ideation and anxiety, as well as employment status, food insecurity, and access to care. The idea behind the study is to prevent long-term health issues among Maui’s survivors — and understanding the conditions in which they live, work, and play is a critical piece of that.

“This is the largest, most comprehensive study ever done in Hawai‘i after a disaster,” says Ruben Juarez, HMSA professor of health economics at UHERO. He is responsible for analyzing the study’s data and reporting its findings.

“If you don’t have good housing, if you don’t have a stable job, your priority is not going to be health,” says Juarez. “In fact, that’s what we’re seeing in our cohort, that many of these people… over 30% of people that we have in the study, this was their first medical check since the wildfire.”

The work of MauiWES is not just to collect data and analyze it, but also to monitor risk factors and inform participants of their medical results to help prevent any long-term problems.

“Without the support of Kaiser Permanente, we would not have been able to sustain this research project, nor expand to include a wider population,” Maunakea says. “Kaiser Permanente’s investment helped ensure that we will be able to continue this vital health research for the sake of our survivors and their future.”

Surprise Findings

Maunakea knew the study would reveal respiratory health issues and increased cardiovascular risks. But, like Juarez, he didn’t expect that so many of the participants who were already showing symptoms weren’t seeing doctors.

“They hadn’t gone to get a medical assessment or health assessment since the fires so that was surprising to hear,” Maunakea says. He explains that ignoring a cough due to exposure to ash and smoke could result in long-term lung problems and an increased risk for heart disease.

Maunakea was also surprised by the extent of the participants’ mental health issues. The study found that more than half of participants have symptoms of depression, with rates highest among middle-aged people. It also showed that 30% of participants have moderate to severe anxiety, 20% have low self-esteem, and 4.4% thought about suicide in the past month.

“Mental health impacts everything about your physical health and gets down to your physiology,” says Maunakea. “They all relate to each other. If you don’t get mental health support, your physical health might decline. If you don’t have access to care, then you’re less likely to take care of your health.”

Disparities in health insurance coverage were also found, with over 13% of participants lacking any health insurance at all. “That’s above the pre-wildfire average, which was about 5%,” says Juarez. “We’re seeing, for Hispanics, 38% don’t have health insurance and that’s something we’re actually working to address.”

Inclusion Matters

The wildfire exposure study is the first in Hawai‘i to include Hispanic representation on a social and biomedical scale. Hispanics make up 11% of Hawai‘i’s population, says Juarez, with the highest concentrations on Maui and Hawai‘i Island.

Community organizations engaged with minority groups to encourage participation in the study. “They’re just really grateful that they were taken into consideration,” says Veronica Jachowski, co-founder and executive director of Roots Reborn, a resource hub for Maui immigrants. The nonprofit helped MauiWES engage with over 200 people in Latino and Compact of Free Association, or COFA, communities.

In the study, more than 60% of Filipinos and Hispanic and Latinos reported very low food security. “Kaiser Permanente recognizes that food insecurity has worsened for survivors living in hotels and has stepped up to increase the amount of grants to community-based organizations supporting feeding programs,” says Jachowski. “This support makes a difference for families and individuals without access to kitchens or the ability to pay for groceries,” she says.

The study also found that the Hispanic and Latino community has the largest number of residents without insurance, at 38%.

“If there’s representation in health studies, then you’re reducing biases,” Jachowski says. “If you have diverse representation, it helps researchers better understand how impacts, specifically fire impacts, affect different groups of people.”

Jachowski says that many of the study’s minority participants are extremely grateful for being included and for having their health results explained to them. “One of the things they always say is, like, ‘It’s good to know, otherwise how else would I have known? I don’t have insurance,’” says Jachowski.

“Kaiser Permanente’s Hawaii Health Access Program has provided critical access to individuals, the majority of whom are receiving access to health insurance for the first time in their lives,” Jachowski says. “This has completely revolutionized access for the most disenfranchised people of Maui.”

Expanding the Study

With the initial report complete, Juarez and Maunakea say the goal now is to expand the cohort from 679 individuals to 2,000, including children for the first time.

Additional funding, which they are pursuing, could also provide an opportunity to extend the study an additional five years or longer. This would allow repeat screenings every year to look at some of the changes and update participants on additional findings.

Juarez and Maunakea are looking at the 9/11 World Trade Center Health Program’s ongoing screenings as a guide.

Participants want the support, says Maunakea. “They want to be included in the study over the long term because they want to know what’s happening and make sure that they’re OK,” he says. “I think that really does help.”

Celebrating Parenthood

Expectant parents are being showered with additional support in a fun and leisurely way. Imua Family Services holds community baby showers each quarter at the nonprofit’s Discovery Garden in Wailuku, Maui. The first ones were in January and April and the next events are scheduled for August and November.

The baby showers are intended to give expectant parents information about all the resources available to them pre- and post-pregnancy, but the events are held like a typical baby shower, complete with gifts, games, massages, and mocktails.

Dean Wong, executive director of Imua Family Services, says that while some parents-to-be have families and friends to throw them baby showers, a lot of people in the Islands do not. “Either their families don’t live in the Islands or they don’t have the means since the fires. Some people don’t have homes. They’re still displaced,” Wong says. “Supporting parents-to-be is one of our most important priorities. The investment from Kaiser Permanente for these baby showers reminds parents and their families that they are cherished and supported. We are creating a safety net of support from the onset so parents will know we are here for them.”

So far, the showers have been very popular. “The first one was for 40 expecting parents, and we put it out there for persons in their second and third trimester, and it filled up within a day,” says Wong. “Once we saw how that went and how well that was received, we kind of made some fine-tunings to the second one and we also increased the number of people that we could gather. And then that one also filled up very quickly.”

Not only do the parents receive gift bags packed with baby essentials and folders full of resources, they’re also able to make friends with other attendees. “The earlier that families can start creating their support circle or their network of friends,” says Wong, “the more support they’re going to have as they’re raising their children.”

The Nonprofit Housing Movement

Hawai‘i Community Lending’s new program addresses the need for more nonprofit affordable housing developments in the Islands.

The vast majority of housing in Hawai‘i and throughout the United States is built by for-profit businesses, and now, with thousands of residents still displaced by the Lahaina fires, more nonprofit developers are urgently needed.

“If we’re going to adequately address the housing shortage for residents, then we need something in addition to the private market,” says Gavin Thornton, executive director of the Hawai‘i Appleseed Center for Law & Economic Justice. “That’s why investing in those nonprofit developments, and removing the financial incentives, is so important,” Thornton continues. “It makes it less about being a smart financial investment and more about being a home for someone that needs it.”

This year, Hawai‘i Community Lending, a community loan fund, introduced a new program aimed at increasing the number of nonprofit developments in the state, especially on Maui.

“We brought together nine different nonprofits who did a weeklong training with us,” says Jeff Gilbreath, executive director of Hawai‘i Community Lending. These consisted of small to midsize nonprofit developers, some of whom already have a few completed projects but lack the staff or capacity to leverage larger dollars for affordable housing developments.

“We took them through kind of the development process, one-on-one, to share with them, like, what do you need as a rental housing developer or a homeownership developer to do this work and expand your capacity,” says Gilbreath. Hawai‘i Community Lending also introduced strategies to bring on partners and shared funding and financing options with them, including information on the federal home loan bank and community development financial institutions.

“Kaiser Permanente heard the need for supporting nonprofit developers in building affordable housing and made an investment to do just that,” says Gilbreath. “It has been 32 years since the Hawai‘i state Legislature made the recommendation to increase the capacity of nonprofit affordable housing developers as a way to address our long-standing housing crisis. We mahalo Kaiser Permanente for listening and taking action so this work can finally come to fruition.”

The training was completed in May and the nonprofits have since been paired with subject matter experts to guide them in their affordable housing plans over the next 12 months. These experts help with questions about acquisitions, federal programs, working with land trusts, and more.

The Hawai‘i Community Lending training program covered topics such as funding and acquisitions. | Photo: courtesy of Hawaii Community Lending

The shortage of nonprofit developers is largely due to developers’ desires to make money, Thornton says. And purchasing resources, such as land, takes time. “You have to build the resources to be able to purchase the land and do the very expensive work of housing development, but if you’re good at it, you make a profit that allows you to do more and purchase more land and do more developments,” says Thornton. “It’s hard for nonprofits to do it.”

More regulations within the private sector could help. In 2022, of the 21,131 housing units sold across Hawai‘i, only 27% were owner-occupied. Thornton says regulating short-term rentals and increasing taxes on investment properties could bring property prices down and potentially bring more of those homes into the long-term housing market. Relaxing zoning requirements could also make it easier to develop multifamily housing, he says.

On completion of the nonprofit developer capacity program, Gilbreath would like to see nonprofits double their development capacity. He would also like to see the program continue year after year.

“These folks are already planning to build more than they had initially thought before getting into the program,” he says. “You’ll see us be better positioned, like say in Lahaina, to rebuild faster because you’ve got more people doing it and at levels that are affordable for families who need it.”

Making a Difference

Each January, nearly 1,000 physicians, nurses, providers, and staff from Kaiser Permanente, along with their family members and other community partners, get together to volunteer in the community. It’s a tradition that began 15 years ago; the company holds its annual day of service on Martin Luther King Jr. Day to honor his legacy.

The volunteers are divided among nine different locations across the state: Paepae o He‘eia, Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi, Papahana Kuaola, the Cultural Learning Center at Ka‘ala Farm and Kalaeloa Heritage Park on O‘ahu; Paeloko Learning Center on Maui; Waipā Foundation on Kaua‘i; and Pu‘uwa‘awa‘a Forest Reserve and Haleolono Fishpond on Hawai‘i Island.

“They’re always needing help. They have massive things they’re trying to do, and we have a lot of people,” says David Bell, MD, assistant area medical director for professional development, people, and service for Hawai‘i Permanente Medical Group. He says it was important to choose nonprofits that would connect physicians, providers and staff physically to the land. All of these sites are tied together as having missions dedicated to ahupua‘a restoration and aloha ‘āina. The group brings medical staff outside to the communities they serve, which also helps to create stronger bonds within the group itself.

Volunteers may be assigned to remove invasive species and replant native ones, restore a stream, remove rocks or work in a lo‘i. “They do a wide variety of things that get them sweaty and outside and moving, and in some instances, dirty. It’s hands on, culturally based fishpond restoration work,” says Keli‘i Kotubetey, founder and assistant executive director of Paepae o He‘eia. “They have been invested in the restoration and the success of the fishpond and that is amazing.”