Honolulu Harbor Isn’t Ready for Climate Change

But the new Kapālama Container Terminal is the first step in an ambitious plan to create a more resilient port and cope with a rising ocean.

The Kapalama container terminal, located on the site of an old army storage area, adds 86 acres to the port of Honolulu. It will be much-needed space for Pasha Hawaii’s cargo operations, which are now crammed into half that acreage on Sand Island. Matson will take over Pasha’s old terminal, extending its current footprint by 44 acres.

But the benefits of this new facility go beyond the extra room for moving containers and roll-on/rolloff cargo such as cars. The new terminal is also far more resilient against sea-level rise and natural disasters than the dozens of piers stretching from Kaka‘ako to Ke‘ehi Lagoon.

A heavy, 20-foot-deep slab of concrete now covers much of the new terminal’s massive yard, which rises 3 feet higher than the rest of the harbor. All told, it’s about 11 ½ feet above sea level at its highest point, creating a buffer from the rising ocean and any damaging storm surge.

On the ground near the water’s edge, hundreds of giant, interlocking beams are stored. They’ll soon be used to build a retaining wall that stabilizes the shoreline of the new terminal – an improvement from the aging Sand Island terminals on the opposite side of the channel.

Those older piers are “built like a deck on a house,” with heavy erosion under the waterline, says Randy Grune, managing director of Hawaii Stevedores. The organization, a subsidiary of The Pasha Group, employs 260 people across Hawai‘i’s harbor system to load and unload cargo.

On a visit in August, construction workers with Kiewit were driving holes into the ground near the bridge to Sand Island, where inserted stone columns will act as “anti-liquefaction in the event of an earthquake,” says Grune. High-intensity vibrations can cause sand to turn to liquid, and the ground at the new terminal includes dredged sand and clays stacked on top of coral rock and limestone.

Solar panels line the roofs of the terminal’s new administrative building, with more panels to come, and five electric gantry cranes will soon harness wind energy using micro-fans that birds can’t enter. The cranes also generate their own electricity with each up-and-down motion.

The site’s renewable energy will be stored in batteries, which allows the terminal to run for “two shifts,” or about 16 hours, says Grune. Rows of electric chargers on the ground can also operate on stored energy, keeping refrigerated containers cool if the power grid fails.

“Technically, the facility is state of the art,” he says. Many of the green-energy features are funded with a $47.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Port Infrastructure Development Program. The Pasha Group and Hawaii Stevedores contributed an additional $92 million. The final cost of the new terminal is estimated at $555 million.

Grune has been waiting for this terminal to be built since the early 1990s, when the U.S. Army, which built the Kapālama Military Reservation at the start of World War II and packed it with wooden storage sheds, made its third and final transfer of land to the state.

The idea to take over the Army site was conceived as far back as the 1980s, and more formal plans were mapped out in 1997. In the years since, repeated efforts to expand and upgrade this section of the harbor have inched forward and stalled.

Grune says he won’t retire until it’s done. The completion date is scheduled for the first half of 2025.

A view of the Matson container terminal on Sand Island. When Pasha Hawaii moves to the new Kapālama Container Terminal, Matson will expand into the area that Pasha will vacate | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

A New Harbor Leader

On the top floor of the state Department of Transportation’s Harbors Division offices, near Aloha Tower, Deputy Director Dreana Kalili’s office overlooks the widest section of the harbor, with views of Sand Island on the other side.

Honolulu Harbor is small compared to many others, with narrow passages and a single point of entry and exit. Container ships share the waterway with barges, tugboats, cruise ships, and fishing and charter boats.

It’s a busy port. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Waterborne Commerce Statistics Center says that 14.7 million tons of cargo moved through Honolulu in 2021, putting it 38th among the 155 principal ports nationwide. (State statistics report lower figures.)

Most of that cargo moves via smaller container ships measuring 2,500 to 3,500 TEU, or twenty-foot equivalent units. For comparison, the world’s largest container ships are in the 20,000 TEU range – nearly six times bigger than the ones seen cutting past Lē‘ahi (Diamond Head) on their trans-Pacific journey to and from the West Coast ports, and to points farther afield.

Kalili stepped into her new job at the end of 2022 as an appointee of Gov. Josh Green, and she brings years of experience with state and city transportation offices. The Harbors Division oversees and maintains 10 ports on six islands.

Her first and most urgent task was an inherited one: Finish the Kapālama terminal by January 2024. Reality set in when live corals, which are protected by the Clean Water Act, were discovered near the piers and had to be moved. Then, a water line connecting the terminal to Sand Island didn’t work as planned and had to be reconstructed.

Delays plagued the project before her arrival as well. The Harbors Division spent years moving tenants from the former military area, which often involved finding somewhere for them to go and then building or renovating their new locations. For instance, a $17 million renovation of Pier 35, near the “fishing village,” was required before the UH Marine Center could move its scientific vessels and operations there in 2016.

“I will move heaven and earth to get this done right,” says Kalili of the new Kapālama Container Terminal, as well as a larger plan to strengthen much of the rest of the harbor’s aging, brittle infrastructure. “The terminal is the cornerstone of the harbor’s modernization plan … and since it’s a hub-and-spoke system, the hub has got to work.”

About 85% of everything that Hawai‘i uses is imported, including food, consumer goods, cars and construction material. And 91% of that comes through the state’s harbors, according to April 2023 statistics from the state Department of Transportation.

And nearly all of that 91% comes through Honolulu Harbor first, with the exception of crude oil that enters through an offshore mooring, according to data from research firm SMS Hawai‘i. From Honolulu Harbor, about 20% of those imported goods are transferred to the Young Brothers’ interisland terminal at piers 39 and 40 for transport by barge to the Neighbor Islands.

If the advantage of that system is efficiency, the disadvantage is increased vulnerability. Hawai‘i is more than 2,550 miles away from the next major port, in Long Beach, California. Honolulu’s port cannot fail.

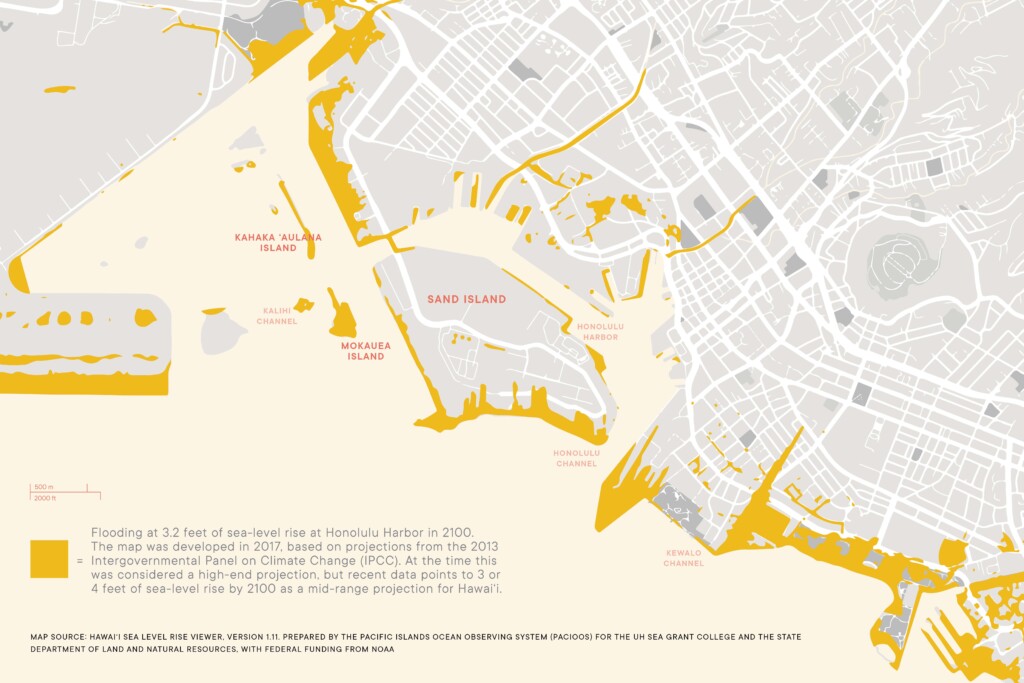

Yet O‘ahu’s southern shoreline is mostly open coast vulnerable to multiple threats: hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes and impending sea-level rise. In 2017, the Hawai‘i Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission recommended the state prepare for 3.2 feet of sea-level rise arriving as early as 2060. That projection could go higher if glacier melting and ocean heating accelerates.

As head of harbors, Kalili is responsible for making Honolulu Harbor strong enough to withstand rising waters and other potential disasters. The weight of that is so heavy, she says with a slight laugh, that it can make her want to crawl into bed and take a very long nap.

Big Challenges With No Roadmap

For resiliency ideas, the project’s sole guide is the Honolulu Harbor 2050 Master Plan. The plan, which was created with input from a wide cross-section of stakeholders and released in 2022, makes it clear that sea-level rise and climate change need to be factors in any modernization.

That Honolulu even has a plan puts it far ahead of most ports in the U.S. By 2021, only 10 of about 300 ports had gone through a resiliency planning process, according to one report. Honolulu’s process was well underway in 2021.

But the master plan can be short on specifics. Infrastructure needs to “accommodate” climate change, embrace “flexible design” and be “adaptive” to changing conditions, such as storm surge and flooding from intense rainfalls. Possibilities include raising piers, strengthening yard pavement, installing wave-dampening sea walls and a host of other measures – all adding up to a rough estimate of about $50 billion when finished in 2050.

Currently, the Harbors Division is self-funded, explains Kalili. Operating expenses and capital improvements are paid for with harbor user fees that are levied when a boat enters the harbor, when it docks, when cargo is offloaded. The money goes into a special fund that’s overseen by the state Legislature.

Before Kalili can move forward with a costly and complex plan, she says she needs a scientific assessment of how rising oceans can affect the nooks, crannies and wide open expanses of the harbor system. She has applied for $3 million in federal money to develop a site-specific “resilience improvement plan” that analyzes what the projections really mean.

“All of these sea-level rise maps just tell me that I might have a problem here,” she says, pointing to a thick line of blue on a map of the harbor. “But there’s no study, there’s no literature that tells me that at this pier, you must do this. Or at this other pier, if you don’t do sheet piles, you can’t move cargo.”

At the end of the process, Kalili hopes to have a detailed plan for 10 priority projects, for which she can then apply for federal infrastructure funding. She expects the most important projects will focus on updating Matson’s soon-to-be expanded Sand Island terminal and increasing the size of Young Brothers’ interisland terminal.

Through this initial process, she’s getting the shipping companies to think far into the future. “In the conversation I’m having with Matson now, we’re planning for 2100,” she says. “What should this terminal look like in 2100? And what do we build in 2023?”

Sea-level rise presents so many variables and unknowns, she says: Will the container ships still make it into the port? Will the cranes be serviceable? Exactly how high should piers be elevated? Will higher piers create runoff into surrounding neighborhoods? How will stormwater drain? Can trucks safely make their way downhill from the piers to the low-lying roads?

And the biggest question of all: “Are these harbors still going to be working?”

Cleaner Fuels for Shipping

While Hawai‘i’s shipping companies help pay for harbor improvements, they take a background role in infrastructure decisions and build-out.

But both internationally and locally, the maritime industry is actively working to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels, and thus reduce its contribution to climate change and sea-level rise. The International Maritime Organization recently set a target of reaching net-zero emissions by “close to” 2050. Shorter-term goals include a 20% reduction in emissions by 2030.

There’s still a long way to go. A recent report from the Global Maritime Forum and other organizations found that 95% of ships are still powered by petroleum products, such as heavy fuel oil, marine gas oil and marine diesel oil.

Hawai‘i’s largest shipping companies are doing better than that. Matson is converting four ships on its Hawai‘i lines to run on cleaner-burning liquified natural gas, and it has commissioned the building of three new cargo ships that are LNG-ready.

At The Pasha Group, Kai Martin, VP for strategic programs, says the company is already operating two new LNG-powered vessels that far exceed international guidelines.

LNG fuel releases 25% less greenhouse-gas emissions than traditional ship fuel, says Martin. In addition, nitrogen oxides are reduced by 90% by using an exhaust gas recirculation system in the main engines. The underwater hulls are “hydrodynamically optimized” to require less energy.

“But the most significant and immediate positive impact is in the reduction of pollutants, especially in the port communities,” he says. “Sulfur oxide, which creates acid rain, is reduced by 99.9%. Particulate matter, which is responsible for respiratory disease, is reduced by 99.9%.”

Martin says that at this stage in the energy transition, the cleanest “green methanol” fuels aren’t yet feasible for Pasha’s fleet. Its vessels are too small to store the amount of fuel needed to power them, and too removed from the limited supply sources. But the company’s environmental commitment is strong, he says.

“Pasha is leaning forward in the transition of the transportation sector to cleaner operations, on the water, in terminals and over the road,” says Martin.

At the new Kapālama Container Terminal, for instance, containers arriving from the West Coast and designated for the Neighbor Islands will be transported to the interisland terminal over water. Randy Grune of Hawaii Stevedores estimates that will take 50,000 truckloads a year off Nimitz Highway, which is “better environmentally, less of a nuisance and more efficient.”

Imagining the Worst

While most goods come to the Islands via ship, the port is just the point of entry. The supply chain extends farther, to a network of roads, distribution centers and even communications systems.

Isolated islands are especially vulnerable to supply chain failures after disasters, says Karl Kim, Ph.D., a professor of urban and regional planning at UH Mānoa and director of the Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance graduate program. He’s also the executive director of the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center and has conducted damage assessments and debris management across the globe.

For Hawai‘i, a relevant example is Puerto Rico. Kim studied the infrastructure breakdown after Hurricane Maria’s powerful winds leveled much of the island and rain flooded communities in 2017. The ports, roads, power and communications fell apart, leaving the island chain in crisis for months.

Those same conditions exist in Hawai‘i, he says. Roads could flood from storm surge, soon to be exacerbated by sea-level rise. The airport could be underwater. Links to other states via rail or superhighway don’t exist. And the closest ports in California are farther away than the one that Puerto Rico depends on, in Jacksonville, Florida.

But maybe worse of all is that Hawai‘i doesn’t have a stockpile of food and water. The operations plan of the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency says the state only has five to seven days of emergency supplies.

Hawai‘i’s “just-in-time” logistics system requires 14 days for goods shipped from the continental U.S. to make their way to store shelves, says the HI-EMA operations plan. When ships continue their regular sailings and trucks make regular runs, everything is fine. The Costcos and Foodlands across the Islands continually restock with fresh infusions of goods.

But their shelves and on-site storage areas are also where nearly all of the “five to seven days of food supply” is located. A disaster would immediately disrupt the supply chain and put people in peril.

“From my perspective, islands in particular need to rethink just-in-time supply chains,” says Kim. He advocates for “resiliency hubs” located across the islands. They could house emergency food and water, and provide electricity for charging devices and cellphone service.

Because an island’s resilience depends on the resilience of ports and supply chains, “we should invest more in terms of disaster logistics,” warns Kim.

One of the worst disasters facing Honolulu Harbor is a scenario similar to when Hurricane Iniki hit Kaua‘i in 1992, says Kwok Fai Cheung, Ph.D., P.E., a professor at UH Mānoa’s Department of Ocean and Resources Engineering. He has spent years studying how waves, currents and storm surge interact to impact shorelines.

Here’s what could happen: A Category 4 hurricane makes landfall around ‘Ewa, on O‘ahu, when the tides are high. In the northern hemisphere, hurricane winds move in a counter-clockwise direction, so the strongest winds would lash more urban areas to the east, such as Honolulu Harbor, says Cheung.

Winds would be a factor in the flooding, but not the only ones. Hurricanes are low-pressure systems that lift the ocean’s surface water by up to 3 or 4 feet. That water moves under the hurricane, increasing the water level of the ocean. Winds blowing toward the shore push the water up further, while offshore waves of 30 to 40 feet intensify the storm surge.

Over several hours, the result would be extensive flooding across the low-lying urban coastline of Honolulu. Sea-level rise would compound the impacts and make the event even worse as “a thicker water layer allows larger waves to reach the shore,” says Cheung.

About 85% of everything Hawai‘i uses is imported, and most of it first enters through Honolulu Harbor’s main channel, seen here. Aloha Tower appears in the center-left distance, with Sand Island Recreation Area at left. On the right is the Fort Armstrong Terminal, which handles cruise ships and foreign cargo. | Photo: Marchello74 / iStock via Getty Image

Where Are the Big Ideas?

Cheung says worst-case scenarios are great for emergency preparedness, and the one he lays out has a 0.1% chance of happening every year. “But for engineering design, you have to look at the probability of an event occurring and the cost of designing for it,” he says.

He doesn’t think many of the big, ambitious coastal infrastructure projects happening elsewhere in the world – often erected after widespread destruction and loss of life from flooding – are feasible in Honolulu, where the coastline is exposed to open ocean.

Many port cities lie inland, linked to the sea by rivers and waterways. Venice, for example, installed a series of barriers to protect it from flooding during exceptionally high winter tides. Rotterdam in the Netherlands has installed an immense storm-surge barrier where a main waterway meets the North Sea. And in the swamplands around New Orleans, a 130-mile ring of floodgates and strengthened levees – the “Great Wall of Louisiana” – was completed in 2022.

In Honolulu, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been studying the feasibility of a lock-and-dam system to protect the harbor. Kalili of the Harbors Division thinks the idea has been ruled out, though a proposal to create a second harbor entrance/exit by elevating the Sand Island bridge, or replacing it with a drawbridge, is still being investigated. The Army Corps of Engineers did not reply to email inquiries.

In reporting this story, Hawaii Business Magazine also reached out to shipping companies, the Honolulu Harbor Users Group, a civil engineering firm, coastal specialists, a maritime consultancy, emergency management leaders and others. Most never replied; others said they couldn’t comment or that they didn’t know enough to assess harbor challenges and possible solutions.

Sea-level rise comes slowly, over decades, but it’s already affecting the harbor. The Honolulu Harbor 2050 Master Plan notes that many drainage outfalls in the harbor are already partially or completely submerged during high tides and king tides, resulting in drainage system backups that can cause flooding upstream. The Harbors Division’s baseyard adjacent to Sand Island Access Road and Ke‘ehi Lagoon also regularly floods during high tides and king tides – a portent of worse to come.

The problem now is finding the best solutions. As Kalili notes, Honolulu Harbor cannot fail, yet how to make it resilient is still unclear.

“When it comes to sea-level rise,” she says, “no one really knows what to do about it.”