Jones Act: Pro and Con

Advocates say it ensures reliable, on-time delivery of everything Hawai‘i needs, while providing a strong U.S. Merchant Marine in time of war or other crises. Opponents say the Jones Act raises prices for everyone in Hawai‘i and puts those who want to export overseas at a disadvantage.

The Jones Act has had a tremendous impact on U.S. shipping for 99 years, but especially in places far from the Mainland like Hawai‘i, Guam, Alaska and Puerto Rico. Local supporters of the federal law say it provides the Islands with a reliable supply of goods and lots of well-paying jobs, and that its demise would saddle us with the uncertainty of foreign shippers.

U.S. Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawai‘i calls the Jones Act a critical underpinning of the local economy and says there’s strong bipartisan support for it in Washington.

Without it, says Hirono, “foreign shipping companies would aim to undercut domestic shippers and each other, and in so doing destabilize an essential segment of Hawai‘i’s economy – the on-time delivery of goods via maritime shipping.

“This cannot happen.”

The law was passed in 1920 as a response to German U-boat attacks during World War I that crippled the U.S. Merchant Marine. The law protects American shipping, shipbuilding and domestic commerce while ensuring this nation has freight ships and crews in times of war and other emergencies.

It’s still doing all that and more, says Matt Woodruff, president of the American Maritime Partnership, a national coalition representing the maritime industry.

He quotes from a 2011 report by the Lexington Institute, a conservative think tank focusing on security and other issues: “Were the Jones Act not in existence, the Department of Homeland Security would be confronted by the difficult and very costly task of monitoring, regulating and overseeing all foreign-controlled, foreign-crewed vessels in internal U.S. waters.”

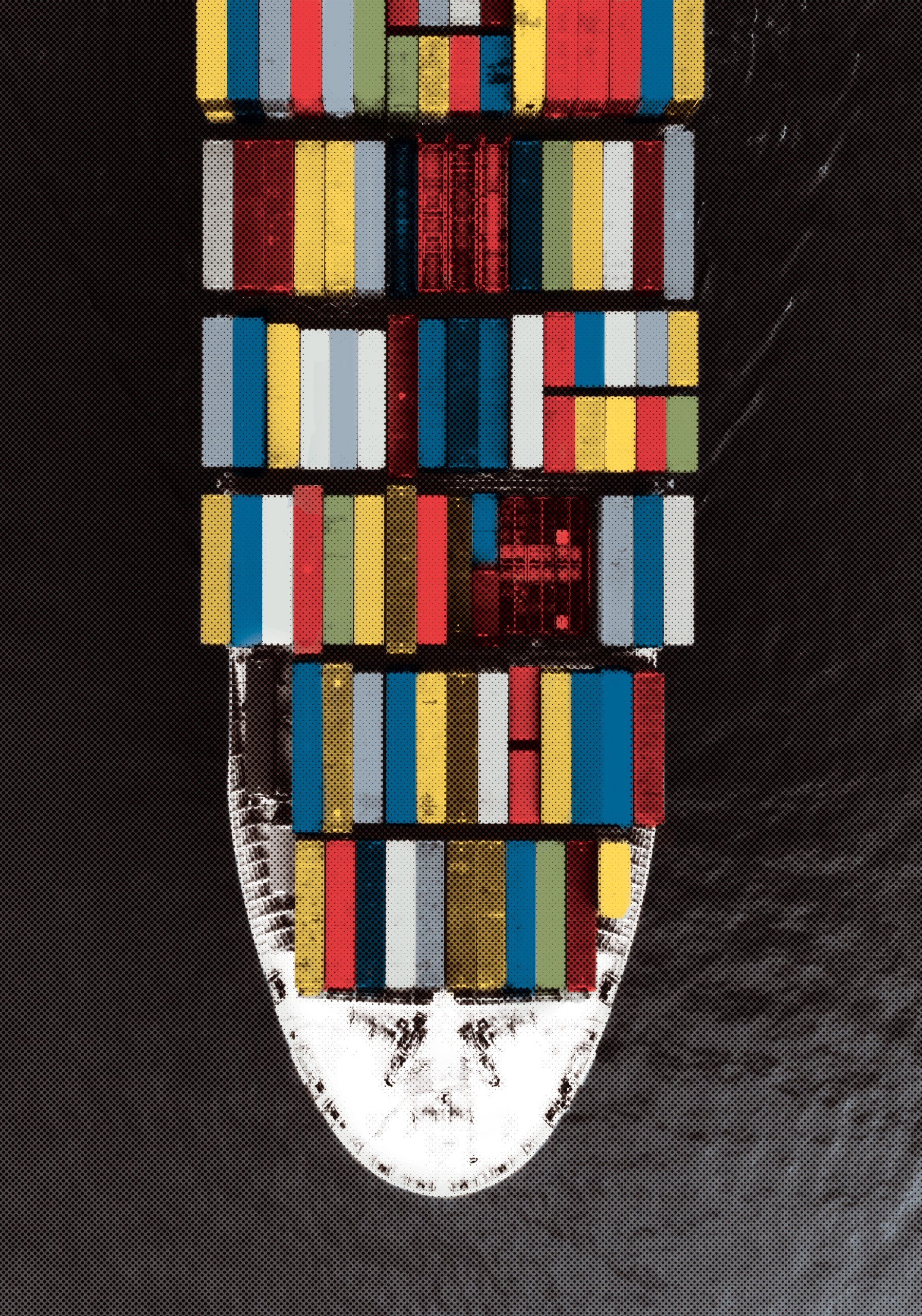

Woodruff says that in addition to “serving as an essential national security asset for the Aloha State, the Jones Act also serves as a strong economic engine for Hawai‘i.” The two biggest companies serving Hawai‘i are Matson, which is headquartered at Honolulu Harbor, with 2,000 employees, and Pasha Hawaii, which has 440 employees. Its sister company, Hawaii Stevedores, has 400 employees. Advocates credit these and thousands of other local jobs to the Jones Act.

“I don’t think Hawai‘i would have the secure and dedicated transportation system in place without the Jones Act,” says Matson President and CEO Matthew Cox. “What it allows us and all participants is to make long-term investments tailored to the Hawai‘i trade that would be absent without the Jones Act. That is a clear benefit to Hawai‘i.”

Hirono, fellow U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz and U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard have all supported the Jones Act. The only member of Congress from Hawai‘i who does not is Rep. Ed Case, who says the law should be reformed or Hawai‘i exempted, because it adds to the high cost of living here and creates a shipping monopoly.

Hirono takes issue with such opposition.

“For years the Jones Act has been a convenient target of blame for the cost of goods in Hawai‘i by national and ideologically driven organizations and their billionaire funders who stand to profit mightily by undercutting U.S. environmental, labor and tax regulations,” she says.

“A variety of other factors contribute to the cost of doing business in Hawai‘i. Repealing the Jones Act would bring great uncertainty and could have a significant impact on Hawai‘i’s economy and our national security.”

Schatz declined to be interviewed for this story, but he has previously fully supported the act. During a 2014 debate with Colleen Hanabusa, when both were vying for Sen. Daniel K. Inouye’s seat, Schatz said:

“I don’t support amending it or repealing it or providing any exemptions, and here’s why. There is a reason that every secretary of defense going back to Ronald Reagan, every secretary of the Navy going back to Ronald Reagan, and every president has supported the Jones Act, and that’s because we need the industrial shipbuilding capacity for (the) United States Navy. This is a national security and national defense issue.”

Michael Caswell, Pasha senior VP of operations for terminals and stevedoring, echoes those sentiments: “It’s not just about protectionism, the military and job creation, it’s about reliable service for the people of Hawai‘i. Not only is the Jones Act part and parcel of our military defense and civil defense, it’s also a way to guarantee consistent delivery to the Islands. You’ve got to have that consistent sourcing.”

“It’s not just about protectionism, the military and job creation, it’s about reliable service for the people of Hawai‘i.”

– Michael Caswell, Senior VP of operations for terminals and stevedoring, Pasha

The Transportation Institute, a Washington-based nonprofit funded by the U.S. maritime industry, responds to critics of the Jones Act in a statement published on its website specifically referencing the Jones Act and its impact.

“The reality is that the difference between U.S. and foreign costs for shipping can be explained entirely by the difference in costs related to taxation, regulation, labor costs and working conditions. Americans have a higher national standard of living, compensation and working conditions. American workers and American companies have to meet national safety regulations. American employers have to adhere to strict U.S. laws.

“American companies, their employees, their vendors and suppliers all have to pay American taxes. All of these costs directly impact shipping costs, and thus American shippers. No matter how streamlined and cost-effective their operations are, they will always be at a disadvantage when compared to foreign operators who do not have to play by comparable rules.”

If the Jones Act were repealed, the U.S. would suffer “a devastating loss of maritime jobs,” shipyards would stop investing in cost-efficient operations and long-term shipping contracts would end, along with the economy of scale built into those contracts, the article says.

In addition to preserving thousands of good maritime jobs, the institute says the act produces millions in spinoff economic benefits in Hawai‘i.

Opponents of the Jones Act say there are many reasons to repeal it. They say it raises prices on just about everything in Hawai‘i, increases costs for local businesses – especially exporters – and actually hurts America’s shipping industry and holds back the local economy.

Michael N. Hansen is president of the Hawaii Shippers’ Council, which has two dozen members. He re-released a 1997 report from the council partly because, he said, no similar credible studies had been done since then on the Jones Act’s impact on the local economy. The report said the Jones Act depressed Hawai‘i’s gross domestic product by 3.1% a year – which works out to $1,014 per person.

Hansen says he hopes the report’s re-release makes the public more aware about the Jones Act’s harm to the local economy.

But Lawrence W. Boyd, a professor of labor economics at UH-West O‘ahu, issued a rebuttal to that report in 1997. He said the Hawaii Shippers’ Council’s report focused on higher shipping costs but downplayed the overall positive impact of the shipping industry’s spending and jobs on the local economy. Repealing the act would actually cost the local economy $257 million a year, Boyd concluded.

Exporters are some of the biggest critics of the Jones Act. Stephen Craven, former chair of the nonprofit Hawaii Pacific Export Council, points out that Hawai‘i companies hoping to ship goods out of state are paying higher costs because of the Jones Act.

“It does raise prices for moving any product that needs to go by sea. In that sense it’s a barrier to trade. It’s raising the shipping costs,” Craven says.

“Cabotage” is a word that refers to the transport of goods or passengers between two places in the same country. “Six or seven years ago the World Economic Forum did an analysis of cabotage laws around the world and came out saying the two worst offenders are the U.S. and China – the U.S. because of the Jones Act, and China has similar restrictions,” he says.

Craven, who served as director of the Pacific Hawaii Export Assistance Center of the U.S. Department of Commerce in the 1980s, believes the Jones Act should be repealed.

“If you repealed the Jones Act in its entirety, the shipping companies raise the specter that foreign-flagged vessels would not step into the breach,” said Craven. “I believe they would, but I can’t guarantee it. And there’s no way to run an experiment.”

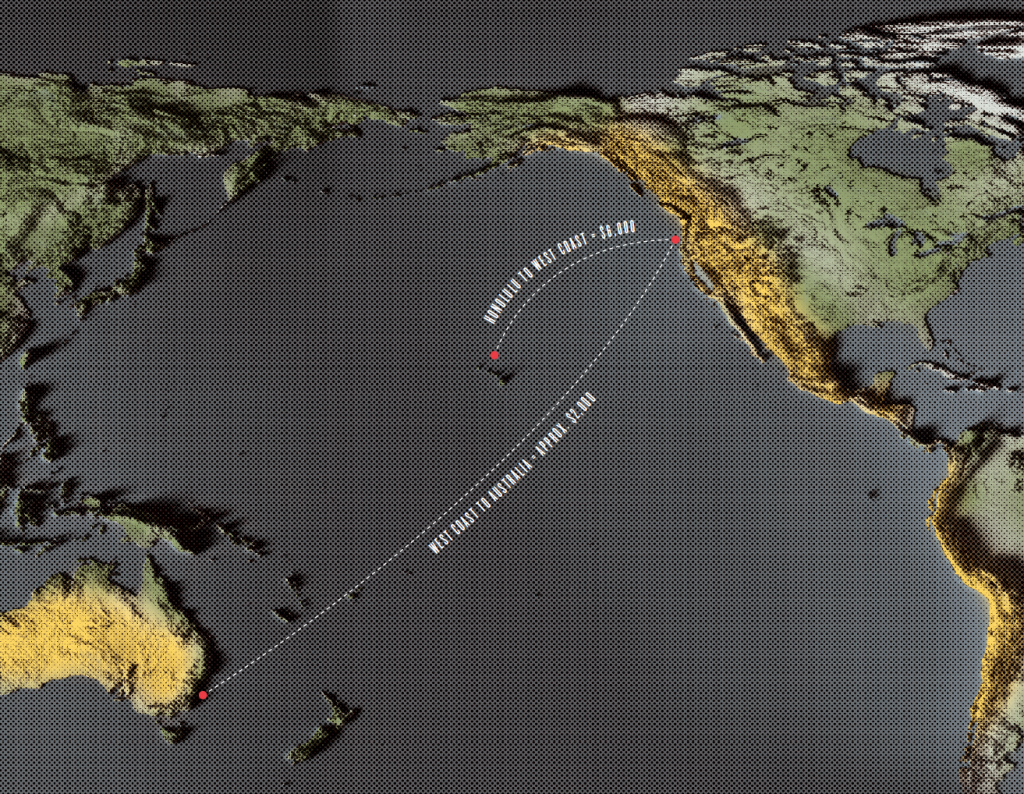

Bob Gunter, president and CEO of Kōloa Rum on Kaua‘i, is contemplating exports to Europe and Australia. But he says shipping a container of his rum just to the West Coast costs $6,000 because of the Jones Act. Once on the West Coast, the container would be transferred to a foreign vessel for the run to Sydney. That trip – from the U.S. West Coast to Australia – would cost about a third of what it costs to ship from Honolulu to the West Coast despite being three times the distance, Gunter says. There is no direct ocean shipping service between Honolulu and Sydney.

In 2018 Kōloa Rum paid $320,000 overall in ocean freight charges, says Gunter. “Without the Jones Act that cost would likely have been half that amount, or even less,” he says.

Those freight costs mean lower profits and slower expansion for the 10-year-old distiller. “We’ve already built it into our standard wholesale price, and have built in the cost of getting those goods to the West Coast (for the Australian market),” says Gunter. “For us there’s no other option.

“People always say there’s not enough business in Hawai‘i for foreign vessels to get into the market. But until you open it up and say, ‘We’re going to try for five years and let’s see what kind of business can be developed with other carriers’ – until you do that you don’t really know.

“It could be a real boon for manufacturers and exporters in Hawai‘i but we’ll never know if not given the opportunity to try.”

Craven says several national studies indicate “the Jones Act probably increases prices on the order of 2% to 4% for communities like Honolulu. It does increase our costs, but perhaps not egregiously so.”

The Grassroot Institute of Hawaii agrees that the Jones Act increases the cost of living in the state, and raises the price of doing business in Hawai‘i. And Grassroot researcher Jonathan Helton says in a June article on the institute’s website that a recent study by the global Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development suggests the U.S. shipbuilding industry would actually grow without the Jones Act.

Grassroot Institute President Keli‘i Akina notes that warfare today is dramatically different than it was a century ago, that the U.S. shipbuilding industry is already much reduced, and that ridding the Jones Act of the build-in-the-U.S. requirement could eventually bolster American shipbuilding by making it more efficient and competitive globally. He says that would also enable companies like Matson and Pasha to buy ships at a lower cost. If those lower costs were passed on to local consumers, that could lower prices in Hawai‘i.

“It could be a real boon for manufacturers and exporters in Hawai‘i but we’ll never know if not given the opportunity to try.”

Bob Gunter, President and CEO, Kōloa Rum

“We’re looking for a solution that benefits all stakeholders, which includes consumers and the shipbuilding industry itself. Updating the Jones Act for the 21st century can bring greater sustainability to the jobs market related to shipbuilding, which allows more entries to the market and would allow more jobs for stevedores. And the increasing supply of affordable ships would allow more parties to participate in the shipping industry market,” Akina says.

He also says “purchasing ships from our allies, like Japan and South Korea and Norway, would allow us to be more competitive commercially with less expensive ships, and (would) cost far less than Jones Act ships to maintain.”

Hansen of the Hawaii Shippers’ Council also hopes to see a repeal of the domestic build requirement so Hawai‘i could be serviced by a wider range of vessels and less expensive ships.

“It would destroy that part of the American shipbuilding industry that builds large oceangoing commercial vessels. We’re talking about maybe 4,000 people, and many have already been laid off. Our major shipbuilding yards just aren’t competitive anymore. We’re inefficient,” Hansen says.

But the shipping industry would be able to buy a wider variety of vessels at lower prices. Hansen says ships built in U.S. shipyards now cost two to five times as much as those built elsewhere. For instance, he says, Japan, China and South Korea all have shipbuilding industries with costs far lower than those in the U.S.

“There are more than 100 kinds of ships being built in the world, and we only have access to three kinds. The shippers are trapped, and so are the consumers, and so is the economy. Why did the flour mill and feed mill in Hawai‘i shut down? Why are we shipping cattle to the Mainland? Why don’t we have a poultry industry in Hawai‘i? There are lots of examples where there simply is no ship available for the kind needed.”

How Hawai‘i’s biggest shipping companies are preparing for the next big storm

Hawai‘i’s two main ocean shipping companies say that if a hurricane hits the Islands, extra container ships would be brought into service if needed and would arrive within days.

Matson, the state’s largest West Coast-to-Hawai‘i shipper, says it has a contingency plan that would put three extra container ships into immediate service, loaded with goods and arriving in Hawai‘i within six days.

“We keep them in a state that allows them to be activated within 48 hours and then it’s a four-day trip” from the West Coast, says Matson President and CEO Matthew Cox. That would be in addition to the regularly scheduled five Matson container ships that arrive weekly at Honolulu Harbor, each with anywhere from 1,000 to 1,600 containers aboard.

Pasha, the state’s second-largest shipping company, could get a reserve ship loaded and to Honolulu Harbor in seven days, says Michael Caswell, senior VP for operations for Pasha terminals and stevedoring.

“Absolutely, we could handle any of the issues,” says Caswell. Two Pasha ships arrive regularly each week and a third comes every two weeks.

Puerto Rico’s Lessons

With hurricane season having arrived in the Central Pacific, and memories still fresh of the devastation in Puerto Rico from Hurricane Maria, Hawai‘i’s lifelines to the West Coast are top of mind. Maria pummeled Puerto Rico in September 2017 and the U.S. island territory is still struggling to recover.

The requirements of the Jones Act were briefly waived for Puerto Rico after that hurricane, but Matson and Pasha are not suggesting a similar waiver as a first response to a disastrous hurricane hitting Hawai‘i.

“When we look at the example of Puerto Rico, there were at least 3,000 loaded containers with goods in San Juan awaiting discharge,” says Cox. “What happened there was right outside the port; roads and bridges were washed out. There wasn’t a problem getting cargo from Jacksonville (the departure port in Florida) to San Juan,” but getting that cargo into the rest of the community proved difficult.

“It’s instructive to look at Puerto Rico,” continues Cox, “and in that case the federal government waived the Jones Act for 10 days. What we would want to do at first is ask the question, ‘Is it necessary?’ If there was some reason we couldn’t anticipate, and operators couldn’t get cargo to Hawai‘i, we certainly wouldn’t stand in the way of a limited waiver, but I don’t think it’s needed.

“The better question is, ‘What is the condition of the roads and bridges that would get the cargo into the community?’ There’s plenty of capacity to carry the cargo, including Matson and Pasha, and barge operators and foreign shipping lines that call (in Hawai‘i) every week, and the U.S. military.”

Disaster Contingency Plans

Before hurricane season began in June, both Pasha and Matson helped stockpile water and food. And both say they have elaborate contingency plans for quick response, as well as a record of participating with state agencies and the military in regular disaster drills.

“Pasha Hawaii works closely with retail customers to support an increase in critical supplies movement to Hawai‘i, and stays in constant contact with them during storms to prioritize the loading and unloading of goods that are most needed,” says George Pasha IV, president and CEO.

“If our container port is damaged, we starve. … So the island problem is exacerbated by the Jones Act because it limits the variety and amount of shipping.”

– David Day, Honolulu attorney and member of the National Association of District Export Councils

International business attorney David Day of Honolulu, a board member of the National Association of District Export Councils, sees a different lesson for Hawai‘i.

“If our container port is damaged, we starve,” he says bluntly. “If we lose our container port terminals here, how are we going to feed O‘ahu? So the island problem is exacerbated by the Jones Act because it limits the variety and amount of shipping.”

Day says 90% or more of the state’s food comes by ship, so a breakdown of port facilities would be disastrous. That is one of the reasons to reappraise the Jones Act and diversify the port infrastructure, he says. If Hawai‘i had facilities to accommodate a wider range of vessels, including smaller vessels and foreign vessels, we would be more resilient in the case of a hurricane.

“Because you don’t have the competition, that retards the development of the infrastructure to support it. If you had multiple ships from different countries coming in, it spreads the risk. You’d have more terminals and some variety of equipment that could handle different ships,” he says.

New Harbor Facilities

Day sees the state’s plans to build a designated Pasha terminal at the former Kapalama Military Reservation as a step toward spreading out and increasing terminal infrastructure.

Pasha’s Caswell says the company has already been working with the state for five or six years on planning the new facilities, which are scheduled to be completed by the end of 2022.

“We have ships that can pull into any terminal or port and we don’t need cranes,” says Caswell. These vessels are called ro-ro, for roll-on/roll-off, and con-ro, a hybrid of a traditional container vessel and a ro-ro.

George Pasha says the new Kapalama Container Terminal at Sand Island will cover 84 acres.

“It’s part of the state’s $448 million Harbors Modernization Plan that will provide the space and infrastructure needed to meet the Hawai‘i shipping industry’s current and future needs, as well as provide additional space to perform emergency response efforts,” says Pasha.

Cox says Matson has intensified its storm preparations.

“We’ve always had (electricity) generating capacity on the terminal, but we’re looking at it more holistically. We have the benefit of the Puerto Rico experience in terms of how to handle a disaster. In an event in which we were on our own for seven or 14 or more days, what lessons could we specifically learn from the unfortunate experience in Puerto Rico?”

Wind-resistant Cranes

Having extra vessels waiting in the wings is just part of the plan. Matson is “hardening” its terminal infrastructure, including upgrading the electrical system, doubling the generator capacity to ensure terminal power is not lost, and strengthening the systems anchored deep in the earth to tie down the giant gantry cranes to the dock so they can withstand gale-force winds of 136 mph with no damage and up to 152 mph with only minor, repairable damage, Cox says.

“On our terminal now we have three diesel generators that provide for generating capacity, and we’re looking at increasing the number to six, plus a battery storage system, plus larger fuel tanks that will allow us to generate more electrical flow and run all six cranes, all computer systems, and continue to support refrigeration of the containers to maintain 100 percent of our operation.”

Twice a year Matson is involved in disaster drills with emergency management agencies and the military, “so that everyone knows what to do,” says Cox.

Matson and Pasha have invested a total of about $2 billion to their Hawai‘i routes in recent years. Among the investments are four new ships that are in or about to join Matson’s fleet and new harbor cranes have been added, and two new ships are scheduled to join Pasha’s service in 2020.

Jones Act Waivers

Waivers of Jones Act regulations have been granted for short periods and specific places. The latest was for seven days to assist recovery in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria hit in September 2017.

Other waivers occurred after Hurricane Harvey in Texas and Irma in Florida, also in 2017; Superstorm Sandy on the Eastern Seaboard in 2012; and Katrina along the Gulf Coast in 2005.