The Heat Is Rising in Honolulu. More Trees Will Help Cool It Off.

Hawai‘i organizations were awarded $42.6 million in federal funds to expand the urban tree canopy. Some neighborhoods need it more than others.

On the hottest day ever recorded in Honolulu – Aug. 31, 2019 – a group of volunteers organized by the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency attached heat sensors to their cars and collected readings around O‘ahu. The project’s timing just happened to coincide with the oppressive weather, brought on by a record-breaking marine heat wave that was cooking up the waters around the Islands.

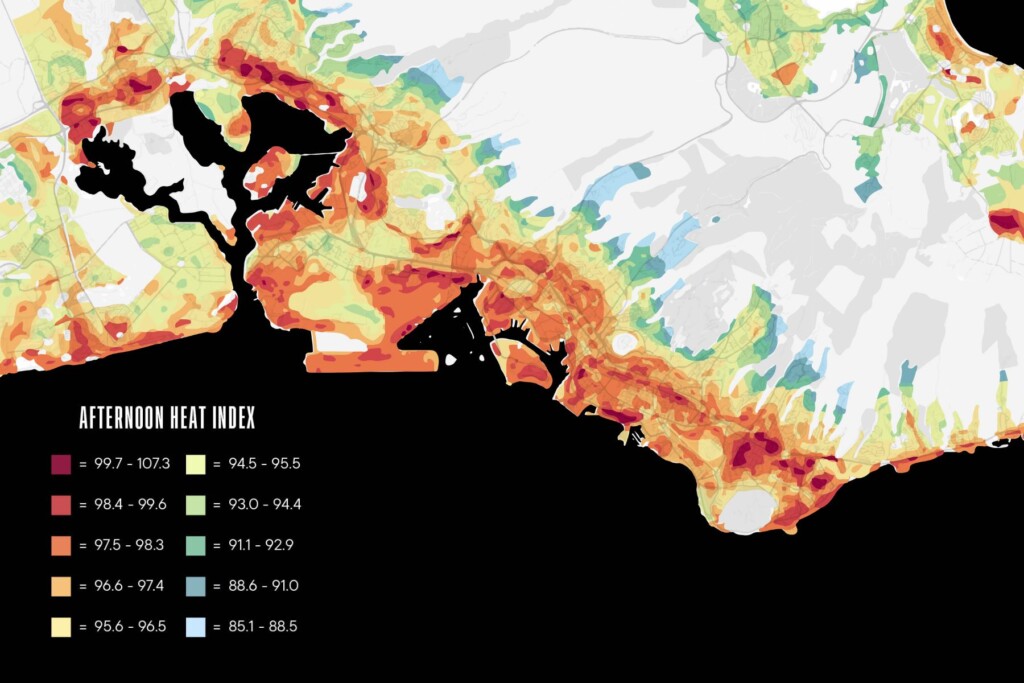

The volunteers recorded startling discrepancies. While the air temperature hit a high of 95 degrees Fahrenheit, the “heat index,” which also factors in humidity, reached 107.3 degrees, logged at the Waimalu Plaza shopping center between 3 and 4 p.m. That was more than 22 degrees higher than the coolest temperature on O‘ahu recorded that hour.

This commercial stretch of ‘Aiea is one of the city’s many “urban heat islands,” where buildings, rooftops and pavement absorb the sunlight and re-radiate it as heat. Few trees are around to cool the area by blocking and reflecting the sun, or, in a process called evapotranspiration, releasing water into the atmosphere through their leaves.

And there’s another layer of heat to consider. The heat index is measured in shade. But the tropical sun can dramatically heat surfaces, making a sunbaked sidewalk or parking lot significantly hotter.

John DeLay, an associate professor of geography and environment at Honolulu Community College, measured temperatures in direct sunlight and under the thick canopy of a monkeypod tree at Makalapa Neighborhood Park near Pearl Harbor. While the air temperatures in the shade and sun were nearly identical, surfaces in the shade were 12 degrees cooler. “That’s why you’re feeling a significant difference in your body temperature,” he says.

About 1 million people live on O‘ahu, most in developed areas that are prone to the urban heat-island effect. Pockets of high heat and low vegetation can be found all along the coastal plains of O‘ahu, including in Pearl City, Waipahu, Kapolei, and Wai‘anae.

In the core of Honolulu, low-lying neighborhoods get dangerously hot, as shown by the dark red areas of the O‘ahu Community Heat Map. At these hot spots – stretching from the Daniel K. Inouye International Airport to residential areas hugging Wai‘alae Avenue in Kaimukī – afternoon temperatures on that extreme heat day in 2019 reached 99.7 degrees and higher.

Jammed with apartment buildings and tightly packed houses, many of the trees and gardens in these dense urban areas have been cut down and paved over for parking. Municipal “street trees,” wedged into small plots of dirt along sidewalks, can have short lives and stunted growth, with little chance of developing the thick, sprawling canopies of mature shower trees blossoming in a park.

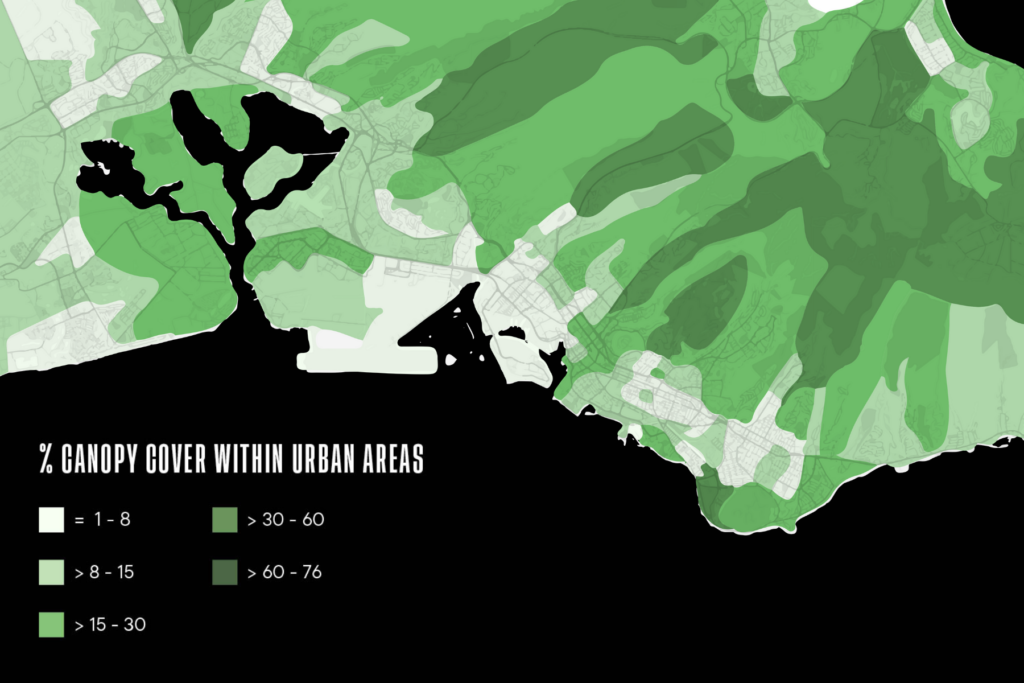

Tree canopy maps created in 2022 by the state’s urban forestry program, Kaulunani, along with the U.S. Forest Service, show that in neighborhoods such as Kalihi, McCully-Mō‘ili‘ili, Kapahulu and the makai side of Waikīkī, and parts of Kaimukī and Pālolo, tree-canopy coverage is less than 8% and as low as 2% – far less than the city’s goal of 35% coverage. Honolulu’s overall canopy coverage is estimated at 20%.

These neighborhoods are also some of the most disadvantaged parts of the city, as shown on the multilayered canopy map depicting income levels. Median household incomes in many of these areas fall in the lowest ranges – from $25,000 to $57,000 or from $57,000 to $76,000 – according to data from the 2015-2020 American Community Survey.

But travel south to north, into the cooler, often rainier and greener neighborhoods at higher elevations, and income levels tend to rise precipitously, a historical pattern that began in the 19th century as those with means moved out of the hot, congested town that had coalesced around the harbor.

Heat Is a Public Health Crisis

Those over-paved areas that don’t have sufficient tree canopy are going to be the hottest,” Brad Romine of the Honolulu Climate Change Commission says. Romine, a coastal resilience specialist with the UH Sea Grant College Program and deputy director of the Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center, has worked with the five-member commission to develop guidelines that track the impact of urban heat and recommend ways for city and state officials to deal with it.

Average temperatures in Hawai‘i have risen 2.6 degrees Fahrenheit since 1950, and about 3.5 degrees at the Honolulu airport, according to Matthew Gonser, chief resilience officer and executive director of the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency. Much of that rise has been in the past decade, and near-future projections show it will get hotter.

“We have seen a marked increase in hot days and warm nights. … It’s one of the most conspicuous, in-our-face results of using dirty fossil energy and the resulting climate changes.” – Matthew Gonser

In a heat wave like the one in 2019, when trade winds collapse and humidity rises, the heat can be punishing on the body.

Dr. Diana Felton, head of the state Department of Health’s Communicable Diseases and Public Health Nursing Division, says that vulnerable people will bear the brunt of the impact of intense heat: the elderly and children, outdoor workers, people with chronic health conditions, and those who can’t afford air conditioning or access health care.

Felton is a lead member of a new DOH working group that’s studying the local health impacts of extreme heat, floods, drought, wildfires, mosquito-borne illnesses and five other climate threats illustrated on a circular chart that Felton calls, with dark humor, “the pinwheel of death.”

The Climate Change and Health Working Group was formed to expand climate-change planning beyond sea-level rise and protecting infrastructure, she says. “No one was talking about the disease and injury that is going to come from climate change, and has actually already come.”

Felton is working with the group to gather evidence of how heat is impacting health in Hawai‘i, and is still sifting through data. But one fact is well documented across the globe: Fatalities rise when the heat index reaches 95 degrees – which can be air temperature of 90 degrees and humidity of 50%, for example – for an extended period.

“The longer the heat wave goes on, you have increased mortality,” explained Dr. Elizabeth Keifer, an assistant clinical professor at UH Mānoa’s John A. Burns School of Medicine, at a seminar in January.

Romine says that urban Honolulu could experience intolerable heat in just a few decades. “I think we could surpass 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming by mid-century, and that’s only going to exacerbate heat waves,” he says. “What that means is more frequent and severe heat emergencies.”

At Honolulu’s Division of Urban Forestry, part of the Department of Parks and Recreation, new administrator Roxanne Adams says her groundskeepers have switched to long-sleeved, high-visibility Dri-Fit uniforms that don’t require the extra layer of a safety vest. She plans to buy cooling neck wraps to supplement the ice water that work crews carry in their trucks.

Roxanne Adams, administrator of Honolulu Department of Parks and Recreation’s Division of Urban Forestry, is responsible for trees in public parks and rights of-way. It’s a big job that requires residents to help: “If neighbors are watching the trees in front of their house, the chances of survival increases greatly. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

“They notice the heat. We all notice that it’s hotter and drier than when we were kids,” Adams says.

“We’re not going crazy when we say, oh my gosh, it’s not as comfortable to sleep anymore,” Gonser echoes. “We have seen a marked increase in hot days and warm nights. … It’s one of the most conspicuous, in-our-face results of using dirty fossil energy and the resulting climate changes.”

Federal Funds to Expand the Canopy

In November, $42.6 million in competitive federal grants, funded by the Inflation Reduction Act and administered by the U.S. Forest Service, was awarded to Hawai‘i groups to provide “equitable access to trees.” In raw dollars, only California, New York and Oregon received more money than Hawai‘i, and in terms of funding per resident, Hawai‘i topped the list.

“It just shows how ready people are to take on this kind of work. … I feel like in five years we’re going to look back and say, wow, this was an amazing time,” says Heather McMillen, an urban and community forester.

McMillen heads the state’s Kaulunani program, an urban and community forestry initiative at the state Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife. Her small office distributes grant money, does outreach and education, and partners with the city, state and nonprofit sector to improve the health and viability of Hawai‘i’s trees.

Kaulunani received a $2 million competitive grant from the U.S. Forest Service, and is launching a project to plant shade trees at select Title 1 schools, where at least 47% of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

McMillen says that if you look at all public school campuses, and extend the footprint to include a half-mile buffer around the school, only 21% would meet the minimum goal of 30% tree canopy. But among the 67% of schools that are designated Title 1, or 197 schools, just 14% have these fuller canopies – an example of disparities in who has access to the cooling benefits of trees.

The project also involves creating a school forester position to work with teachers and staff on maintaining the trees. “Planting the trees is the easy part. Helping them grow to their full potential … is a much longer-term commitment,” McMillen says.

Heather McMillen, coordinator of the state Kaulunani community and urban forestry program, says: “Trees are not beautification. Trees aren’t nice to do. This is critical infrastructure, and it needs to be part of the planning process. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

Other groups receiving funding include the Akaka Foundation for Tropical Forests and the Friends of Amy B. H. Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden, both on Hawai‘i Island, and various county, state and UH Mānoa projects.

The largest U.S. Forest Service award in Hawai‘i, at $20 million, went to Kupu, a 17-year-old nonprofit that has trained thousands of young people, many from disadvantaged backgrounds, for jobs in conservation and natural resource management. In the process, its teams have cleared about 150,000 acres of invasive species and planted 1.5 million native specimens.

CEO and co-founder John Leong explains that most of the $20 million grant will be re-granted to other groups in Hawai‘i and the Pacific region over the next five years, with Kupu providing technical expertise. The application process is expected to open in the second quarter of 2024.

In the world of urban forestry, the Kupu grant is a huge amount of money. For comparison, Hawai‘i’s 2023 state allocation for urban and community forestry from the U.S. Forest Service is $1.5 million. Many people interviewed for this article say they’re eager to find out who will win sub-grants from Kupu and what projects will be funded.

The broad theme of the federal grant is to expand the tree canopy and cool down places where people live, but the finer details require projects to benefit underserved areas. Projects linked to creating green jobs and engaging communities in planning and decision-making are also prioritized.

The O‘ahu community heat map identifying urban “hot spots” was developed by the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency. It’s based on peak afternoon temperatures recorded on Aug. 31, 2019. The full islandwide map can be found at tinyurl.com/oahuheatmap

Kupu’s mission lands at the intersection of all those goals. Leong says it will seek out organizations that will bring trees to “under-resourced” areas, both urban and rural, and build up a workforce of arborists and conservation workers.

He’s especially focused on training and educating, both for those doing the work and the broader community that benefits from more trees, more jobs, and an understanding of how climate change will impact them and what they can do about it.

“When you educate a young person, you’re really impacting about seven people: their parents, their grandparents and their siblings,” he says.

In the fight against climate change, “We have all the right stuff in our Islands to be a model for the rest of the world,” Leong says. “But we also have to engage communities at the grassroots level, empower them and give them the resources they need on the ground to be successful. That’s really what this grant is about.”

Why Trees Are Important

In 2016, the nonprofit Smart Trees Pacific released the dispiriting results of its urban tree-canopy analysis. Nearly 5% of the tree canopy, or about 76,600 trees, had disappeared in a four year span. The consensus among experts is that things haven’t improved since then.

Trees are cut to make way for larger houses or more parking space for multifamily homes. They’re cut because they’re old, and then not replaced, or because it’s easier to remove a tree that’s interfering with a sidewalk or utility project than to work around it. They’re cut because a homeowner is worried about liability. And many times, they’re cut because someone wants a better view or just can’t deal with the rubbish.

“It’s death by a thousand cuts,” says McMillen from the state’s Kaulunani program. No one tree-removal project accounted for a significant portion of the loss, she says, and it’s happening on both public and private land.

Gonser, from the city’s climate change office, says street trees are sometimes destroyed maliciously. That’s an added insult when you consider all the nurturing required in a tree’s first few years, before it’s planted in the ground, and “it’s vandalism of a city asset and infrastructure.”

Trees can take years, even decades, to get large enough for their benefits to dramatically overshadow their costs. “They cost money to maintain, as do sidewalks, as do stoplights, as do fire hydrants. But unlike that kind of infrastructure, trees are the only kind of infrastructure that increase in value over time,” McMillen says.

An analysis conducted for the city’s Division of Urban Forestry found that for every dollar spent on Honolulu’s trees, the city gets back $3 in benefits. Estimates in many other cities show even more positive cost-benefit ratios.

On the global level, trees are called the “lungs of the world” for their ability to pull enormous quantities of carbon dioxide from the air, which they store in their trunks and branches. With the help of the sun, trees then release oxygen through their leaves. A dramatic NASA time-lapse video shows the forests of the Northern Hemisphere sucking carbon dioxide from the air through photosynthesis as trillions of leaves open in the spring and summer.

The lungs metaphor goes deeper as well. For people who feel connected to trees, or just aware of their contributions, trees don’t just make life on Earth possible, they make it worth living.

Trees provide shade and cooling. They clean the air by removing pollutants, and provide food for people and habitats for birds. They protect against flooding by absorbing stormwater and help prevent beach erosion.

Trees reduce noise in the city, and traffic calms along tree-lined streets. In hot climates, their shade makes a city more walkable and bikeable.

And there are intangible benefits too, McMillen says: Trees are the “keepers of memories” for anyone who spent time playing in them as a child, and they can strengthen social connections among neighbors sharing fruit from backyard trees. They help define a place and remind us where we are on this planet.

Trees can even change cortisol levels, heart rates, breathing and mood. At the Tropical Landscape and Human Interaction Lab at UH Mānoa, students’ physiological, “preconscious” responses were captured as they viewed images of trees. Lush, green canopies triggered states of relaxation while images of canopies with their tops lopped off had the opposite effect, says Andy Kaufman, an associate professor of tropical plant and soil sciences and a landscape specialist.

For all their benefits, trees and other vegetation are often taken for granted and treated as disposable. “Nature is so important to us, but landscaping is the first thing to be cut and the last to be addressed,” says Kaufman, who founded and runs the interaction lab. “We should embrace living in nature,” not work against it, he says.

Kaufman has seen many examples of trees chain-sawed at the top, which lets disease and pests enter the tree and weakens the branches that grow back from the stumps. He’s seen trees clear-cut from an ‘Ewa school’s campus, a “complete streets” project in ‘Aiea that failed to include trees, new buildings constructed with only a tiny strip for plantings, and – in an especially egregious case – miles of oleanders along the Moanalua Freeway ripped out and replaced with concrete.

The biggest challenge, Kaulunani’s McMillen explains, is to get policymakers, developers, homeowners and anyone who cares about their neighborhood to change the way they think about trees.

“Trees are not beautification. Trees aren’t nice to do,” McMillen says. “This is critical infrastructure, and it needs to be part of the planning process, not an additional thing to do if you have funds or if you have the inclination.”

Where Trees Are Needed Most

The City and County of Honolulu’s Division of Urban Forestry can trace its roots to the Shade Tree Commission, which started in 1922 to deal with the ongoing issue of how to cool a tropical city, now getting hotter with climate change. “I would love for our city to be a city in the forest. I’m a firm believer that trees make everything look better, cleaner and more friendly,” says Adams, the division’s administrator.

Before joining the division last year, she spent two decades overseeing the more than 4,000 trees at UH Mānoa. The campus is an accredited arboretum and includes what’s probably the nation’s largest baobab tree, which is at least 110 years old.

Her new role overseeing the estimated 250,000 trees in city and county parks and public rights-of-way offers a vastly larger canvas for planting – the entire island of O‘ahu – but also far more challenges.

At the moment, Adams’ division is finishing a complete inventory of all city trees, which will let her team know exactly what trees they’re responsible for, which ones need attention first and where to plant next. The project, funded in 2022 with $300,000 in federal assistance, will be done before the end of June.

She’s also been focusing on filling vacancies that have accumulated over the past decade. Adams says her team is nearly fully staffed to do the hard physical labor of digging holes and planting trees, many of which start from seeds in the division’s nursery at Kapi‘olani Regional Park.

Once the tree inventory is complete, Adams says her goal will be to plant where shade is needed most, such as in Kalihi, Mō‘ili‘ili, Kapahulu and Kaimukī, and outward to ‘Ewa, Nānākuli and Wai‘anae.

“We’re definitely looking at equity and will be planting in those neighborhoods,” Adams says.

Kaulunani and U.S. Forest Service maps track tree canopy coverage and heat vulnerability, and also data such as median family incomes in a particular area, the presence of impervious surfaces, the prevalence of asthma and cardiovascular disease, the number of residents by census tracts and Native Hawaiian populations. That fuller picture of which neighborhoods are being left behind – economically, environmentally, medically – seems to be shifting the conversation about where to focus efforts.

Gonser, from the city’s climate change office, says that, over time, patterns in how a community is designed and developed “can exacerbate increasing temperatures and make it hotter in places. There really are disparities or inequities as a result of these practices. … We’re trying to make sure that we bring focused, strategic attention to those neighborhoods.”

While planting in an older neighborhood full of hardened surfaces and densely packed housing requires more effort than in more remote areas, among urban foresters, anything is possible. Their often-repeated motto is “the right tree in the right place with the right care.”

In unshaded neighborhoods, for example, sections of concrete can be removed from sidewalks to make space for plantings. Clusters of small street trees can be planted together to create a bigger canopy. For something more ambitious, car lanes could be used for planting large canopy trees, such as the monkeypods that line Kapi‘olani Boulevard from Atkinson Drive to South Street – a grove that’s been designated as one of Hawai‘i’s “exceptional trees.”

While trees can pose difficulties, those difficulties are surmountable, Kaufman from UH Mānoa says. “There are always ways to restructure roads. You can always work around trees. … Green infrastructure should be business as usual in every municipality.”

He and a team of researchers recently found that using Silva Cells – a modular, suspended pavement system developed a decade ago – is the most promising way to grow healthy street trees in Hawai‘i. Unlike other methods they tested, the roots stayed contained rather than sprawling out and up, damaging infrastructure. He says the long-term tests were the first ever conducted in a tropical urban environment, where trees and their roots grow year-round.

It’s not a magic bullet, Kaufman explains. But better planting techniques could help expand the canopy in some of the city’s oldest, most crowded neighborhoods, where working-class and middle-class people began moving more than a century ago, as new tram lines opened up new possibilities.

The Old Suburbs

Honolulu, like everywhere, has been defined by shifting migration and development. Through much of its history, one trend seemed clear: wealthier people tended to congregate in the hills or near the water, while the less affluent settled in the low-lying, hotter middle.

The first hint of a city started in the early 1800s, as whalers began stopping here for parts, provisions and rest, and a makeshift harbor settlement emerged to meet demand. By 1845, the capital of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i had officially moved from Lahaina to a now bustling Honolulu.

Wealthy ali‘i and white settlers were the first to leave the core, says William Chapman, the interim dean of UH Mānoa’s School of Architecture and a professor of American studies, with expertise in historical preservation. They fanned out for more space, less disease and often cooler climates.

Queen Ka‘ahumanu, for example, regularly retreated to her Mānoa house, near the present-day Waioli Kitchen and Bake Shop, where she died in 1832. In 1853, the German physician William Hillebrand built a house and planted trees at the site of Foster Botanical Garden.

In 1882, Anna Rice Cooke and Charles Montague Cooke, both members of missionary families, built a home on Beretania Street, on the site where the Honolulu Museum of Art is now. When electric streetcars were introduced in 1901, and the first automobiles traversed the city’s roads, large estates were constructed in the hills of Nu‘uanu Valley. Some are now occupied by foreign consulates.

After the kingdom was illegally overthrown by white businessmen in 1893, the global sugar and pineapple trade accelerated, along with immigration. Contract laborers first arrived from China in the mid-1800s, followed by people from Japan, Korea, Europe, Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

Kaka‘ako in the late 1800s was filled with small houses for artisans, stevedores and service workers, many of whom were Native Hawaiian, says Chapman. Working-class and artisan-class residents began branching out into Kalihi and Liliha.

Honolulu Tree Canopy Map, 2021. Prepared by EarthDefine, U.S. Forest Service, NOAA and Hawai‘i Division of Forestry and Wildlife.

Streetcars opened up neighborhoods far beyond the harbor area. Many Japanese and Chinese workers, freed from contract labor that was deemed illegal in 1900, migrated east along King Street, renting or buying modest wooden houses stretching all the way to the rice fields of Mō‘ili‘ili.

By the 1920s, satellite communities as far away as Kapahulu and Kaimukī were developed as the rail lines expanded, while along the coast, affluent people had moved to the Diamond Head area and were expanding into Kāhala.

John Rosa, an associate professor of history at UH Mānoa, says his great-grandfather on the Chinese side of his family built a house on 16th Avenue during Kaimukī’s first wave of development. In the 1950s, his grandparents moved to a house in the breezy mountains above the neighborhood, in Maunalani Heights, where he grew up.

Many prosperous families had moved mauka into Mānoa Valley and Nu‘uanu, where whites-only “tacit agreements,” sometimes written into covenants governing new subdivisions, kept others out, explains Chapman.

These rules also determined the physical environment. “There were a lot of restrictions,” Chapman says. “It had to be a substantial lot. Residents weren’t allowed to build walls over a certain height. They couldn’t open a gambling den or a bar or a restaurant.”

The racial elements of the exclusionary practices were dropped after World War II, and the cooler, leafier neighborhoods opened to a mixture of people. Among the new Mānoa residents were many upwardly mobile Japanese residents who had gone to UH Mānoa on the federal GI Bill, Rosa says.

After the war, and before zoning laws were enacted in 1961, high-rise apartments were constructed amid the single-family houses of Waikīkī and Makiki. Eventually, cars brought people to the new postwar suburbs of ‘Āina Haina and Hawai‘i Kai, and then even farther from the city.

Today, some of Honolulu’s old working-class, mixed-use neighborhoods can feel improvised, a mismatched collection of small wooden bungalows, motel-style walk-ups with open corridors, taller “bare-bones” buildings with interior hallways, and their posher cousins, the newer high-rise condos.

“Planners aren’t the ones that actually build cities. It’s the developers,” Chapman says. “It’s like a rowboat and a tanker. The tanker is the developers, and they pretty well decide what’s going to happen.”

For example, setback regulations, which started in 1969, are still just 5 feet. “You’re supposed to put planting in the setback, but they’re often not very robust,” he says. “Developers probably see vegetation and trees as a luxury add-on. And if they don’t need to do it, they won’t do it.”

Chapman sees the old neighborhoods as “transitional,” with new housing set to rise in places like Isenberg Street in Mō‘ili‘ili. There, a 23-story tower is under development by the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, and on Kapi‘olani Boulevard, the Kobayashi Group is constructing a 43-story condo.

But with no requirements for trees, shade, green walls or green roofs – on new high-rise projects or throughout the older neighborhoods – these urban heat islands will only get hotter.

Greening the City

Community groups have been focused on trees and shade since at least 1912, when the newly formed Outdoor Circle, a volunteer women’s group, planted 28 monkeypod trees in Honolulu’s ‘A‘ala Park. Those trees still stand today.

The organization has spent the subsequent 112 years planting and protecting trees in public spaces. In 2017, the Outdoor Circle helped found Trees for Honolulu’s Future, a nonprofit group dedicated to increasing the urban tree canopy, advocating for laws and policies, and educating the public.

The group’s president, Daniel Dinell, spearheaded the educational component of the Makalapa Neighborhood Park project, which quantified the impact of shade on how we experience heat. Young “heat island investigators” from the underserved area nearby learned to measure trees, read temperature sensors and test hypotheses.

Among the organization’s many projects, Dinell is also leading a group of “citizen foresters” to map the trees in Kaimukī and locate places to plant, and he’s working with the city to get trees in the ground. One of the big obstacles to new street trees, he says, is getting homeowners and renters to water the trees in their early years, when they’re still weak.

“Just activating the community is key to the goal of increasing the tree canopy,” Dinell says. Government agencies can’t do it alone, Adams, the head of Honolulu’s Urban Forestry Division, says. “It’s critical that our neighborhoods, our friends, our family chip in and help us get this done. It’s a kōkua thing. If neighbors are watching the trees in front of their house, the chances of survival increase greatly.”

Residents can contact Adams’ division to request a street tree, at 808-971-7151 or DUF@honolulu.gov. The city selects hardy trees that won’t become invasive pests; most native trees aren’t able to survive in harsh urban settings with vehicle pollutants and poor soils.

On Hawai‘i’s Arbor Day, about 4,000 trees, including fruit trees, are given away across the Islands. The next annual event, organized by Kaulunani and government, nonprofit and community partners, is scheduled for Nov. 2.

At the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency, an ongoing effort to plant 100,000 trees on O‘ahu has passed the halfway mark. The agency’s online map tracks city plantings as well as trees planted on private property and larger restoration efforts.

The project, says Gonser, the office’s executive director, “was intended to be a campaign of awareness, and to celebrate those that are the true champions out in the community.” He says many plantings have not been recorded yet.

All of these efforts are steps in the right direction, and indications that more people and organizations recognize the value of trees in a time of rising heat and sweltering cities.

Globally, 2023 was by far the warmest year on record, according to NOAA. And while the heat affects everyone, it’s much worse in urban heat islands bereft of trees. And it’s particularly punishing for people without air conditioning.

“We’re already facing a lot of heat in these urban areas. It’s a problem we need to fix now,” says Romine, of the Climate Change Commission. “And if we start addressing it now, it’ll make these communities safer, more comfortable and more equitable, now and for the future.”

What Experts Would Like to See Next

- Require trees and green features on new construction and refurbished buildings

- Expand Honolulu City and County’s exceptional tree program

- Encourage more species diversity to reduce vulnerability to disease and pests

- Incentivize homeowners and businesses to use trained arborists

- Require homeowners to get permission before removing large trees

- Replace dark roofs with solar-reflective panels or coating

- Add green roofs and green walls with decorative or edible vegetation

- Increase staffing and funding for urban forestry divisions

- Plant trees at bus stops and playgrounds

- Set up cooling centers and subsidize A/C for low-income residents.