Why Hawai‘i’s Wildfires Are Growing Bigger and More Intense

The disaster on Maui is a sign of things to come as invasive grasses spread across the landscape and extreme rain-drought cycles intensify their fuel loads. Here's the science behind Hawai‘i’s wildfires, and the people who are fighting to stop them.

One segment of the massive 2018 wildfires that burned an estimated 9,000 acres of Leeward Oʻahu started next to Eric Enos’ farm in Waiʻanae Valley.

Ka‘ala Farm and Cultural Learning Center backs up to wild lands of guinea grass and spindly haole koa trees. Beyond that are the slopes of the Waiʻanae Range, with Mount Ka‘ala towering overhead at 4,000 feet.

Enos has spent decades carving out a small oasis from the former sugar cane fields. Water for the farm’s terraced lo‘i kalo and shade trees originates from Kānewai stream in the Waiʻanae Kai Forest Reserve, which then funnels into dike rock and through hand-laid pipes to his property.

But everywhere around them is hot and dry.

On Saturday, Aug. 4, two busloads of students were visiting when Enos spotted smoke rising from a nearby spot along the narrow road leading to his property. He called the Fire Department, which was already fighting another blaze in Nānākuli. When they arrived, the trucks couldn’t get close as the fire was spreading downwind toward the town, blocking the road.

“We were totally trapped,” recalls Enos.

He gathered the young people near the taro ponds and hoped the winds would keep pushing the fire away. But as some of the flames crept toward them, Enos and his team furiously doused them with 5-gallon buckets of water from nearby Honua Stream.

It bought time for helicopters from the Honolulu Fire Department, the state Division of Forestry and Wildlife, and the Department of Defense to arrive, dumping water from huge buckets.

The fire burned across three valleys, turning the air black and forcing residents to flee. It took two weeks before rains finally extinguished the stubborn patches in the back of Mākaha Valley, says Clay Trauernicht, a botanist and fire scientist in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management at UH Mānoa.

“If you had asked me earlier if climate change is affecting fire, I would’ve been skeptical,” he says. “But after the 2018 fire … I would say we’re definitely seeing the impacts of climate change. Record-breaking heat and incredibly low humidity levels are driving these fires beyond the ability to put them out.”

While Leeward Oʻahu is a hotspot, brush fires are happening more frequently on every island, and in every location, even the wet windward coasts.

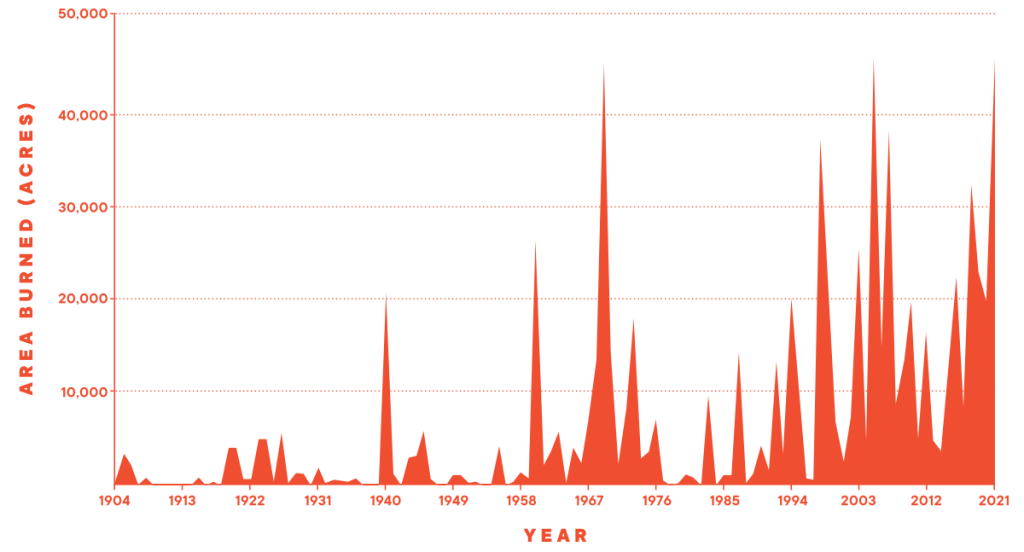

Experts such as Trauernicht are sounding the alarm that the rapid spread of invasive grasses, pronounced rainfall and drought cycles that intensify the grasses’ fuel loads, and more people doing reckless things – sometimes intentionally, as with the 2018 Leeward Oʻahu fires, but often accidentally too – have resulted in a 400% increase in wildfires over the past several decades.

From 1904 through the 1980s, Trauernicht estimates that 5,000 acres on average burned each year in Hawai‘i. In the decades that followed, that number jumped to 20,000 acres burned.

The good news is there are ways to slow or stop fires, from targeted grazing to creating fuel breaks to ensuring “defensible spaces” around homes. While Hawai‘i rarely sees the kind of infernos that California gets, dramatic changes are happening to the landscape that are making conditions more dangerous.

The Trouble With Guinea Grass

Sometime around the turn of the 20th century, after the plantation economy had been established, wild grasses from the African savanna made their way to Hawai‘i.

Guinea grass, or Megathyrsus maximus, is remarkably hardy. While the grass turns pale and lifeless during droughts, it bounces back after a single rainfall. In heavy rains, long green shoots can sprout overnight.

Guinea grass grows quickly after rainfall, adding to its fuel load during dry conditions. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

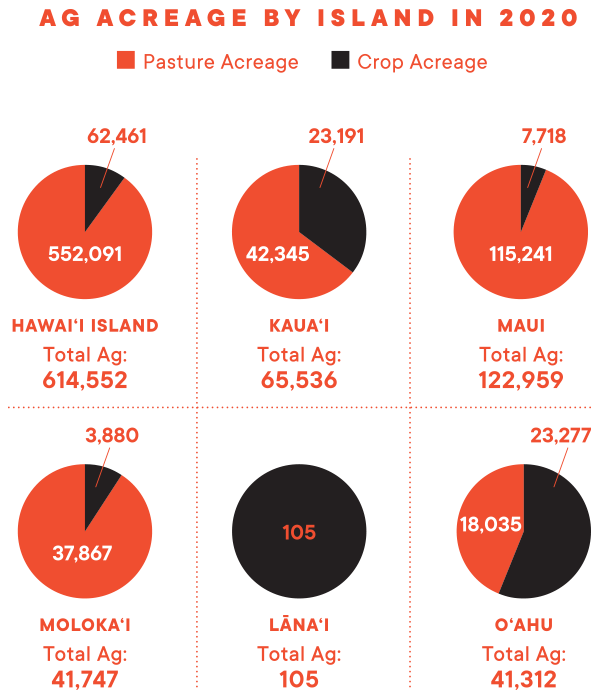

Guinea grass and fountain grass, along with nonnative scrubland, now cover about a quarter of Hawai‘i’s land, or 1 million acres, says Trauernicht. Much of that land was once used for farming and ranching; it now lies vacant, the remnants of faded industries.

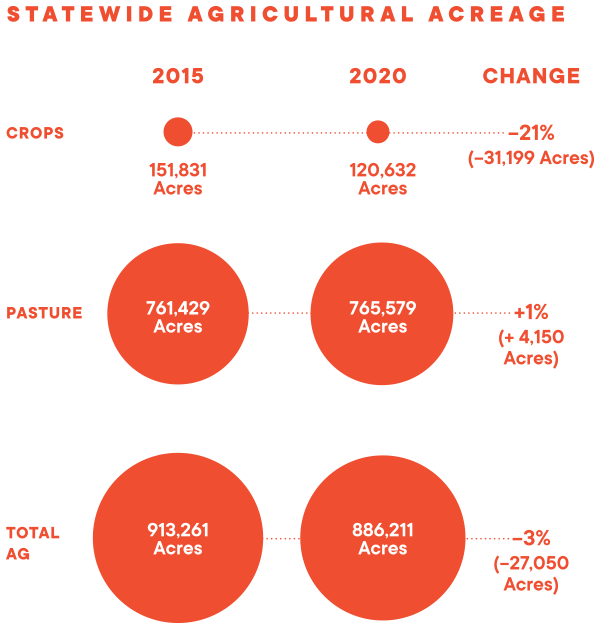

A 2020 report from the Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture shows that, of the 1.93 million acres designated for agriculture in the state, only 6.2% was being used to grow crops. Another 40% was being used as pastureland. That’s less cropland than in the 2015 census, which was taken shortly before the closing of the last sugar mill on Maui, HC&S, the Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co.

With many grazing animals gone and fields left fallow, nonnative grasses flourish. And they’re highly flammable. A single spark – from a campfire or a car’s hot catalytic converter rolling across a field – can trigger massive wildfires, such as the July 2019 blaze in Maui’s central valley that burned through 10,000 acres of old sugar cane fields.

“These monotypic strands of grasses are monstrous,” says Trauernicht. “They just attain enormous fuel loads. I can’t find parallels anywhere, and I’ve dug deep in the literature, that compares to the amount of fuels that we get with guinea grasses and even fountain grasses.”

The worst-case scenario, says Trauernicht, is when heavy rains trigger rapid growth, followed by severe drought, which withers the grass and turns it into tinder. “And, boom, our fire risk goes through the roof.”

In September, nearly all of the state fell into the range of abnormally dry to the most dire category, exceptional drought, according to the federal government’s U.S. Drought Monitor.

In the past three years, about 30% of the state has experienced long periods of harsher drought conditions – categorized as severe, extreme and exceptional – where fire risk is high. But the most intense drought in the past two decades was the week of March 9, 2010, when 6.6% of the state was under exceptional drought conditions. Such conditions can kill cattle and crops.

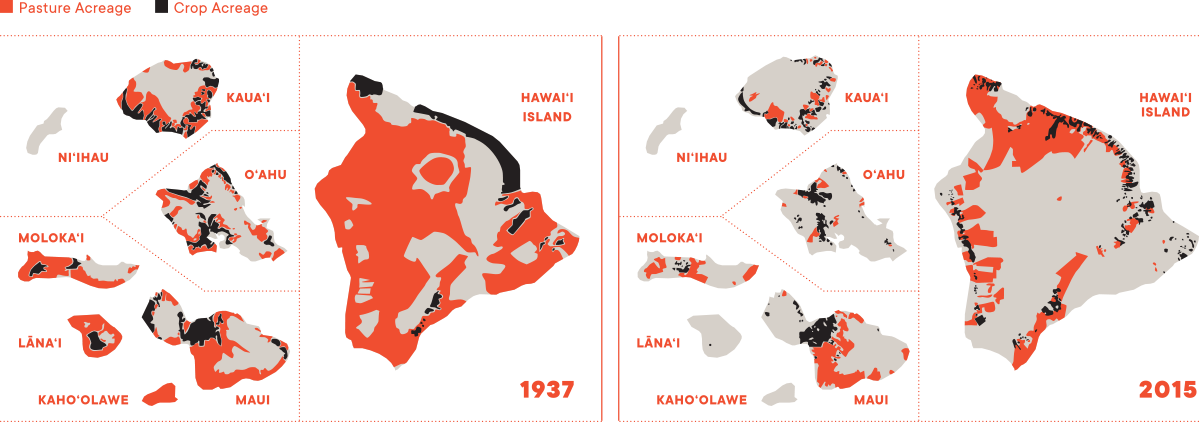

Ranching and Farming in Hawai‘i: 1937 vs. 2015

The maps show major shifts in the amount of land devoted to grazing and growing crops over 78 years. Pastures are marked in red and farms in black. As Hawai‘i’s economy changed and agriculture has shrunk, more land is left fallow and grazing animals are removed. Guinea grass and other nonnative species take over the landscapes. They have extremely high “fuel loads,” making fires larger and more intense.

Native Vegetation Lost

Wildfires spread to Hawai’i’s native ecosystems as well, especially dryland forests, which have been devastated by fire. About 90% of those forests have been lost over the past century.

Michael Walker, head of the wildland fire program at the state Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW), has seen entire wiliwili forests destroyed by grass-driven fires.

“They’re not fire adept at all,” says Walker. “When a fire rolls through, it’s just going to kill 100% of them, and they’re not going to come back. The native plants don’t have that ability.”

Walker got interested in fire ecology as a student at the University of Florida, where he examined the fire-adapted ecosystems of the Southeast.

He calls the area “the lightning strike capital of the continent,” where fire is a dominant force in the ecosystem’s evolution. Many pine cones, he explains, only release their seeds with the heat of intense fires; the seeds then germinate in the bare mineral soil left behind.

But Hawai‘i is altogether different. Historically, lightning is rare and volcanic activity was fairly short in duration. Unlike much of the mainland, Hawai‘i’s plants evolved “in the absence of fire as an ecosystem driver,” he says.

The result is a grass-fire cycle, “where every time a forested area burns, it becomes a more hospitable environment for these nonnative grasses and shrubs to reproduce and thrive,” says Walker. He calls it “the nouveau Hawaiian savanna.”

What’s often missing, he says, are large animals to eat the grasses, as you’d find in Africa. “The pasture grasses and other grasses have started to alter these landscapes in a way that it’s hard to reverse.”

Area Burned Each Year in Hawai‘i Has Risen Dramatically in Recent Decades

Starting in the 1990s, an average of 20,000 acres burns each year, which is about four times the average seen in 1904 to 1989. The spike in 1969 was from a single wildfire in Pu‘u Anahulu on the Big Island, which burned 41,000 acres. In 1904, after a huge wildfire burned for months on the Hāmākua coast, Hawai‘i’s forest reserve system was launched and began reporting on wildfires.

Battling Wildfires

Walker, along with about 200 others at DOFAW, have taken workplace cross-training to new levels. When “gray sky” duties call, teams drop their “blue sky” activities, such as grant writing and restoration work, and gear up to battle blazes.

With 26% of the Islands under the forestry division jurisdiction, much of it rugged and difficult to access, firefighting can be challenging work. Depending on the weather and terrain, the teams might use hand tools to shovel dirt and bulldozers to cut firebreaks – earthen paths where vegetation has been cleared.

Until recently, their firefighting duties were completely unfunded, says Walker. Fire suppression had been bundled into DOFAW’s tiny $600,000 annual budget for all forestry and wildlife efforts. Some of its equipment is from the Vietnam War era.

But after the past legislative session, Walker says state funding rose to $3 million, supplemented with grants and federal assistance from the U.S. Forest Service. It’s enough to start purchasing off-road water-hauling trucks that can better reach wildfires and building water tanks in remote areas where helicopters can refill.

DOFAW firefighters put out hot spots on Aug. 6, 2018, along the firebreak above Eric Enos’ property. Native trees are currently being planted in the foreground area. | Photo: Clay Trauernicht

The DOFAW team supports county firefighters working in urban areas as well. When the eastern slope of Mānoa Valley burned in September 2020, Walker worked with a “hand crew” on the hillside and directed helicopter drops and water cannon blasts from fire trucks parked along the streets.

“I was concerned it was going to burn houses and more forest,” recalls Walker. “Wild grass burns really hot and really quickly. The fire can get out of control.”

Hawai‘i’s Agricultural Footprint Continues to Shrink

The drop between 2015 and 2020 was mostly the result of Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co. closing on Maui, which took 38,810 acres of sugarcane out of production.

Source: Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture, “2020 Update to the Hawai‘i Statewide Agricultural Land Use Baseline.”

Source: Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture, “2020 Update to the Hawai‘i Statewide Agricultural Land Use Baseline.”

Big Island Burns

That happened last year, when the largest fire in recent years exploded on the northwest slope of Mauna Kea on Hawai‘i Island. The 2021 Mana Road fire, which burned 42,000 acres, or more than 62 square miles, started on a red-flag warning day and was swept by winds up into the mountains then branched in different directions.

“There was no way to do a frontal attack, and the ruggedness of that area really didn’t lend itself to being able to put dozer lines in quickly or being able to attack from the flanks,” says Eric Moller, Hawai‘i Island deputy fire chief, who was working on the fire’s incident management team.

As more people and resources arrived from DOFAW, the National Park Service and the U.S. Army Garrison on Hawai‘i Island, the fire eventually was wrestled under control. But it was a herculean effort, with resources stretched thin.

“In California, you’ll hear about a 4,000-acre fire just north of LA with 200 firefighters on the scene,” says Moller. “We’ll have a 20,000-acre fire with 35 people fighting it,” including volunteers.

For context, fire scientist Trauernicht says the Mana Road fire burned 1% of the island’s land area. Over the course of a year, wildfires in California burn, on average, 0.7% of the state’s land area. Across the islands, the percentage of land burned each year can rival that of Western states.

Hawai‘i Island faces some novel challenges as well, such as wildfires crisscrossing through fountain grass, an invasive grass found on the island’s arid leeward side. In the morning, as the winds travel down the mountains, fire is pushed along the dry tops of the grass, burning it off and exposing the moist bunches underneath. But at night, he says, the winds reverse course and send the fire back up to burn the now dried-out understory.

“It’s insidious,” says Moller, “and it bounces back from fire very, very quickly.”

Moller says he isn’t an alarmist, but people should know that conditions are changing. “We’re getting bigger fires,” he says. “Lightning strike fires were very rare when I got here (in 2003), yet now it’s starting to happen more often.”

Elizabeth Pickett, co-executive director of the Hawai‘i Wildfire Management Organization (HWMO), agrees the changes are pronounced.

“Fifteen years ago, we talked about a fire season, and it had a lot to do with when the fuels (grasses) were dry and when it was most windy. Now we’re starting to see fires happen on both the wet and dry sides of every island,” says Pickett.

The threat is real and not going away, adds Moller. “And we don’t have the money or equipment to effectively safeguard all the communities. They need to take those steps themselves.”

Communities Take Action

Elizabeth Pickett began working in wildfire management as an environmental scientist interested in coastal waters. It became clear, though, that Hawai‘i’s ocean health is directly linked to wildfires, which strip the vegetation and send reef-smothering sediment into nearshore waters.

With Nani Barretto, Pickett leads HWMO, a small Waimea-based nonprofit that punches far above its weight. The organization has become a hub for the wider community – scientists, government agencies, large landowners, neighborhood groups and firefighters at the county, state and federal levels – to share information and resources.

And Hawai‘i, she warns, is a fire-prone state that hasn’t prepared properly for the risks. “Our budgets, our policies, legislation, fireworks laws – nothing has really caught up to the threat that we see on the ground.”

The organization’s first major success came in 2005, when it helped the Kona Coast’s Waikoloa Village create a firebreak between homes there and the wildlands. Just days after the project was completed, a 25,000-acre fire burned to the break and spared the houses.

Pickett focuses on large-scale issues, such as mapping high-priority areas for vegetation management. But she also works directly with residents across the Islands to help them protect their homes and communities.

The organization’s fire-prevention guides, including Ready, Set, Go and the Firewise Guide to Landscape and Construction, advise people to clear away debris from gutters and under houses, keep lawns short, trim the lower branches of trees, replace wooden fences with stone, invest in shingled roofs made with fire-resistant material, and many other strategies.

Some residents are taking steps. In Makakilo, Craig Fujii, a retired fire captain from Alameda County, California, is well aware of the risks. His house looks out on the foothills of the Wai‘anae Range, with sweeping views to Diamond Head.

From his backyard, a low rock wall drops to arid land below, one of many “urban-wildland interfaces” across O‘ahu’s heavily populated south side. He’s cleared away shrub trees and grasses and created a small-scale firebreak. The long-term goal is to make the rock wall higher to better protect against the wind and potential flying embers.

He says the biggest worry is a brush fire that starts near the highway, gets swept up the mountain by ocean winds and gains speed as the rising heat of the flames preheats the fuels on the slopes and intensifies the fire.

People Are Triggers

Pickett, Trauernicht and other researchers analyzed wildfire records from 2005 to 2011. They found that grassland and shrubland made up the vast majority of land burned (an average of 8,427 hectares, or 20,815 acres, per year).

But 66% of wildfires actually started in populated areas, and there are far more of those kind of fires than most people realize. O‘ahu sees about 500 to 600 ignitions a year, says Trauernicht, most of which are quickly extinguished by the Fire Department.

In total, there were 7,054 reported wildfires across the state during the seven-year span studied, and 6,218 listed a cause of ignition. Of those, 1.5% were attributed to natural causes, 2% to arson, 16% to accidents and the rest were “undetermined” or “unknown.”

But in nearly all cases, people are to blame, with the top causes being campfires, fireworks, and heat and sparks from vehicles and equipment, says Pickett.

In the high-risk fire zone of East Honolulu, Elizabeth Lockard, who lives near the entrance to Koko Head District Park, has witnessed numerous ignitions in the park. One was in 2011, when an employee at the park’s public shooting range discharged a flare gun, charring a patch of mountain above the targets.

In 2017, another started higher up the mountain, behind the shooting range. Ocean winds helped spread the fire and black smoke, forcing hikers to scramble down to safety. An investigation into the cause was inconclusive.

Several other fires have broken out in the park, none of them minor, says Lockard. She says she’s frustrated with the nonchalant attitude of investigators and the fact that nothing changes. “But what is the catalyst to change if there’s not loss of life or property?” she asks.

Matt Glei, who lives in Kalama Valley, remembers coming home on the evening of July 4, 2010, to see fire racing toward his house. That blaze started from illegal fireworks.

“The firefighters were running up the mountain in full kit, dragging hoses from a pump truck,” recalls Glei. “It was scary to watch, and it’s hard, hard work.”

Glei is a leader of the Kamilonui Valley/Mariner’s Cove Firewise Community, which is part of a nationwide network committed to reducing fire risk. The local Firewise branch, which is overseen and funded by HWMO, has 15 active groups in the Islands, most on Hawai‘i Island.

The sole O‘ahu community started after a series of fires in 2017 and 2018 burned the valley’s slopes and threatened the farmhouses and nearby suburban development. Today, about 450 households have banded together to protect their neighborhood.

In June, for example, the community rented dumpsters to clear away debris lining an unused gravel road, which serves as a firebreak between a fuel-covered mountain and two dozen homes in Mariner’s Cove.

Managing Vegetation: Where to Start First

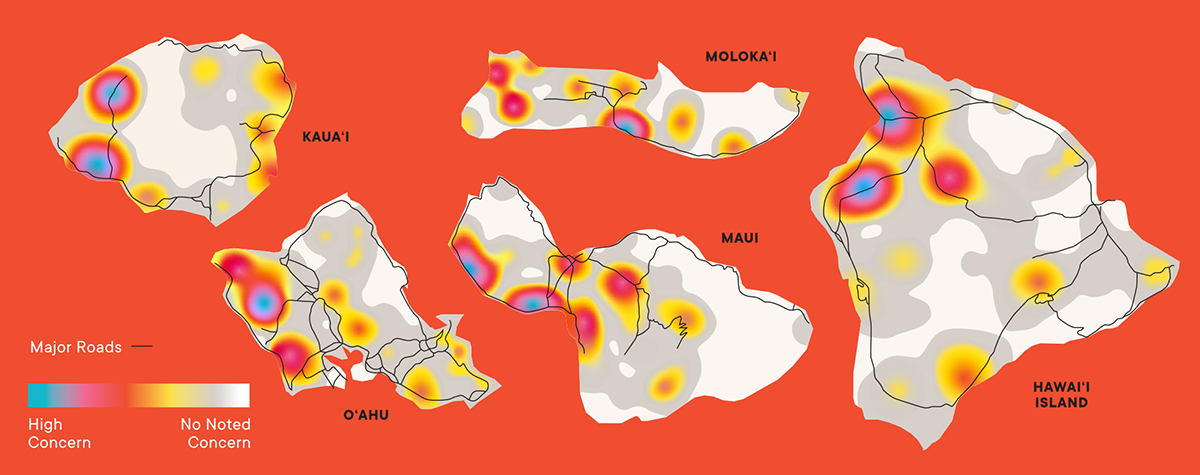

Managing wild grasses and shrubs is essential for reducing wildfire risk. In 2018 and 2019, the Hawai‘i Wildfire Management Organization brought together 182 people – lawmakers, landowners, ranchers, emergency responders, community members and others – for six planning meetings across the Islands. Participants mapped areas that have hazardous vegetation and weather, high rates of ignitions, and that pose high risks to communities, natural resources or infrastructure. The results are heat maps that target areas to prioritize.

Source: Hawai‘i Wildfire Management Organization, “A Collaborative, Landscape-Level Approach to Reduce Wildfire Hazard Across Hawai‘i, 2018-2019.”

Fighting Back with Animals and Trees

While most of the Firewise communities use people and machines to clear away vegetation, others are turning to managed grazing.

On O‘ahu’s West Side, Ka‘ala Farm and Cultural Learning Center operates on a shoestring, but its land management and fire mitigation practices are ambitious. Enos says the operation recently removed 40 tons of trash that was dumped along Wai‘anae Valley Road and cleared an area for fire trucks to turn around.

The team is now clearing swaths of scrubland and planting trees that do well in the environment, such as mango, sandalwood, ‘ō‘hi‘a lehua and ‘ulu. Much of the hard work is handled by 10 hungry sheep, which strip away the bark and leaves of haole koa and devour the green blades of guinea grass.

A.K. Ahi, left, and Eric Enos with grazing sheep at Ka‘ala Farm and Cultural Learning Center. | Photo: Chavonnie Ramos

A.K. Ahi teaches at the center and leads the grazing effort. He cordons the sheep in a mobile paddock and moves them from patch to patch. Eventually, as the animals breed, he plans to move the flock to a large tract of land that adjoins the center.

“The ranch side has 1,000 acres, and it’s all dry grasses. It’s a huge fire hazard for us,” says Ahi.

While free-roaming cows and other hoofed animals can wreak havoc in forested areas, “strategic, managed grazing is our best tool for fire-fuels management and risk reduction,” explains Pickett. She says there’s a strong “anti-ungulate” faction among environmentalists, but that Hawai‘i’s wildfire problem would be far worse without grazing.

Ahi also volunteers to help clear a nearly milelong firebreak on a northern slope above the center’s property, which is managed by the Wai‘anae Mountains Watershed Partnership.

Yumi Miyata, the partnership’s coordinator, has introduced a vegetated section to the firebreak made up of native plants, which students in Wai‘anae, Nānākuli and Mililani help grow and plant. She says the goal is to restore sections of the forest and shade out the flammable understory of grasses.

These kinds of vegetated breaks, or lines of trees planted on the landscape, helped slow down the intensity of the Mana Road fire on Hawai‘i Island, says Trauernicht.

While low humidity and high winds caused the fire to rip through grazed pasture land, it bypassed areas with trees. “You can see that the fire burned around those areas,” he explains, while the grazed areas failed to stop the fire’s spread.

Many of the island’s large landowners are looking at how they can “disrupt the continuity and connectivity of the grasslands with tree planting,” he says. Parker Ranch, for example, is working on a huge reforestation project on 3,300 acres of grassy pastureland on the slopes of Mauna Kea.

Trauernicht says he’d like to see the state government get on board and subsidize agriculture as a public good. “There are lots of examples in Europe of forestry agencies paying farmers to graze fuels, just for the fire risk reduction.”

In the meantime, the Parker Ranch restoration and smaller projects like those at Ka‘ala Farm are making an impact. Now, Pickett says, is the time to scale up efforts throughout Hawai‘i’s vulnerable communities and landscapes.

“One of the biggest things we need to prepare ourselves for in relation to climate change is fire,” she says. “The more we do toward wildfire preparedness, protection, mitigation, and even community building is climate change resilience in action.”