Hawai‘i’s Filipinos Are Stepping Out from the Shadows

10 personal stories illuminate the triumphs and challenges of the second-largest ethnic group in the state.

Roland Casamina | Jade Butay | Patricia and Marissa Halagao | Raymart Billote

Sergio Alcubilla | Lalaine Ignao and Eric Ganding | Agnes Malate | Larry Ordonez

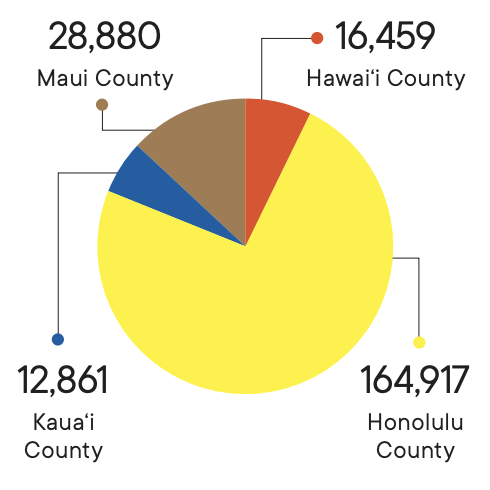

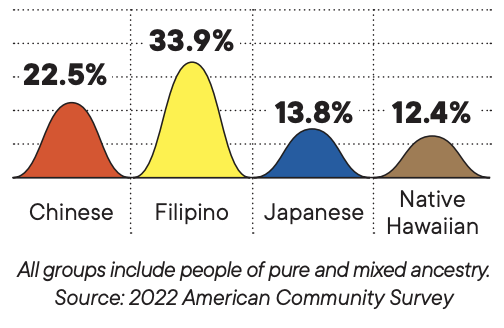

Filipinos have been in Hawai‘i since the 1860s, according to naturalization records. Today, 367,525 people in Hawai‘i have Filipino ancestry, in part or entirely. That’s 1 in every 4 residents. Some have local roots that stretch back many generations and others just arrived from the Philippines in the past few years.

I am one of those 367,525 people. My grandparents arrived in the 1970s and I grew up in Waipahu, graduated from Waipahu High and UH Mānoa, and have worked at Hawaii Business Magazine since 2021.

In these pages, I will tell the stories of 10 Filipino Americans in Hawai‘i – including accounts of their successes and resilience, their hard work and pride, but also of the loneliness and shame some of them have felt, and the pain of prejudice and exclusion they’ve endured. Their stories help illuminate Hawai‘i’s past and present, from Filipino perspectives.

In between each personal story, I will include facts that explain some of Filipinos’ shared histories and their current realities.

Being Filipino Helped Him Succeed

Roland Casamina says his recipe for success is simple: “There’s no formula other than eagerness.” Then he adds, “It’s about me being Filipino.”

The company he started in 1995, House of Finance, funded almost $235 million in mortgage loans in Hawai‘i in 2021, Casamina says.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ranked House of Finance as the No. 1 guaranteed rural housing lender in Hawai‘i. (For lending purposes, the USDA considers all of O‘ahu as rural except for Hawai‘i Kai to Pearl City, and Mililani, Kailua and Kāne‘ohe.) House of Finance has also ranked among Hawaii Business Magazine’s Top 250 companies and been on the magazine’s Most Profitable Companies list several times in recent years.

Though he often faced difficult times when he was young, Casamina says those humble beginnings contributed to his success. He was born in the Philippines and came to Hawai‘i in 1968 at 14. His first job was as a busboy while attending Farrington High School; later, while at UH Mānoa, he worked as a waiter.

“I was not always proud to be a Filipino,” he says, adding that people in other ethnic groups in Hawai‘i looked down on Filipinos and that he often felt overwhelmed. On his first day of college, he looked around the classroom and saw there were no other Filipinos. Casamina felt like “the dumbest guy in this class” and the least qualified. He continued to sometimes feel that way, though he ranked toward the top of the class and landed on the dean’s list.

His outlook changed when he graduated with a bachelor’s in business administration in 1976 and was offered a job as a branch manager at International Savings and Loan. At that time, Casamina says, the bank was looking for a Filipino to help attract more Filipino customers.

He says he felt unqualified because he was 22 and had no banking experience, but “the VP of the bank at that time said, ‘I’ll take a chance on you,’ and after three months of training, he said, ‘You’re ready to go.’ ”

“I was shocked.”

Back then, Casamina says, his “dreams were so small” that he had to keep adjusting them as his career advanced.

“I was happy to just have food on my table,” he says. Eventually, he decided that he would never allow himself to “stoop that low” as to feel shame again about his heritage and culture. Instead, he would embrace both, with confidence and pride.

His hard work paid off: Casamina became VP of International Savings and Loan and only left the company to open House of Finance in 1995 when the bank was bought by a bigger bank.

Casamina and L&L Hawaiian Barbecue founder Eddie Flores Jr. spent much of the 1990s raising money for the future Filipino Community Center in Waipahu, and were driving forces behind its completion in 2002. They served as its founding president and vice president, respectively.

Casamina spearheaded the $14.5 million fundraiser and has personally donated close to $900,000 to the center.

It is described as the largest Filipino community center outside of the Philippines and serves as a hub for educating all of Hawai‘i about the ethnic group’s contributions to the Islands.

Casamina also established a $50,000 endowed scholarship at UH Mānoa’s Shidler College of Business and has a student leadership center there named after him and his wife, Evelyn.

His advice: “Keep working hard and be loyal to the company you work for.”

In 1906, 15 men were brought here from the Philippines to work on sugar plantations and this first group of contract laborers laid the groundwork for the many more “sakadas” who followed. From 1906 to 1946, over 100,000 Filipino men were recruited by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association.

A Filipino Voice in State Government

Jade Butay has over 20 years of experience working in state government and business and is now the state’s director of labor and industrial relations. He says he owes his leadership skills in part to his family’s humble beginnings in the Philippines.

“Growing up in the Philippines instilled hunger and inside of me, a desire to succeed,” says Butay. “It taught me the virtue of hard work, shaped my childhood and built my character.”

As a child in the Philippines, he says, he had lots of friends but left them and everything else behind when his family moved to Hawai‘i in 1983. He was 13.

Butay says his parents moved his family to Hawai‘i in search of a better life. But the working-class family had difficulty assimilating and Butay describes those early days in America as “inauspicious.”

As a middle school student, he had a newspaper route in a hilly part of Salt Lake. “I had a route in my neighborhood and every day after school, I would deliver the Honolulu Star-Bulletin,” Butay recalls. When he would load up his bike on Sundays, the papers were especially thick and heavy, he says.

It was a test of his will and gave him a sense of responsibility and accountability. “When you’re an immigrant, you want to have your own income or resources – you don’t want to be dependent” on your parents.

That same thinking carried over to UH Mānoa, where his business degree included double majors in accounting and finance because, he says, he wanted to be “financially independent.” And through it all, he looked to his parents’ sacrifices and hard work as motivation.

“As an immigrant, you start at the bottom, and you have no place to go but up.”

So that’s where he went: Butay graduated from UH with honors, and eventually got his master’s at Babson College, which calls itself the “best college for entrepreneurship.”

He has 13 years of experience working in the private sector, where he’s secured contracts for housing and commercial projects and created marketing plans to help businesses succeed.

His public service experience started when he was an undergraduate working as a legislative assistant for the University of Hawai‘i Professional Assembly. Later, he served as a budget analyst and legislative coordinator for the Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism and then as a congressional aide to Neil Abercrombie.

Butay has worked in the administrations of Hawai‘i’s three most recent governors, dating back to when he was a deputy director in Abercrombie’s administration, first at the Department of Transportation, and later at the Department of Labor and Industrial Relations. He currently heads that department under Gov. Josh Green.

Under Gov. David Ige, he served as director of the Department of Transportation for over five years. During his term, he says, DOT completed four major airport construction projects: the $270 million Mauka Concourse at the Honolulu airport, consolidated car rental facilities at Honolulu and Kahului airports, and a federal inspection services station at Kona airport.

Butay says people sometimes referred to him as a unicorn in state government “and it wasn’t a good thing.” He says it’s because, at one point, he was the only Filipino in the Cabinet. It’s different now: In Green’s administration, he is one of three Filipino Cabinet members.

“We have a long way to go,” Butay says of Filipino representation in state government. “It’s extremely important that the Filipino community is at the table. I need to make sure our voices are heard – ensure we are not out of the picture when critical decisions are being made.”

By 1932, Filipinos made up 70% of the plantation workforce, according to a 1939 Bureau of Labor Statistics report. The report says they were paid an average wage of $467 in 1938, compared with $651 for Japanese workers.

Filipinos Underrepresented in Higher Education

Patricia Halagao, an educator for more than a decade, has worked on getting more Filipinos into higher education and more educational opportunities for Filipino students.

She remembers asking a Filipino student, “Why do you think you’ve never learned about yourself in school?”

The student replied, “It’s probably because Filipinos haven’t done anything important.”

“That was like a big dagger in my heart,” says Halagao. “As an adult, you don’t really make those kinds of connections later in life. But when you’re a child, that would be kind of your assumption – if you don’t see yourself, you haven’t done anything.”

Patricia Halagao, chair of curriculum studies at UH Mānoa’s College of Education, and daughter Marissa Halagao, founder of the Filipino Curriculum Project

As the chair of curriculum studies at UH Mānoa’s College of Education, she has advocated for equity by increasing the number of Filipinos and other underrepresented groups in college and pursuing careers in higher education. While she was on the state Board of Education, she pushed for the development of policies on multilingualism and for the Seal of Biliteracy, which is now awarded upon graduation to students who demonstrate high proficiency in both of the state’s two official languages (English and Hawaiian), or in either of those two and at least one additional language.

The seal encourages second-generation Americans to take pride in their multilingual abilities.

She and other leaders also successfully encouraged the state Department of Education to move Filipino students out of the Asian category in public schools data. She says it was important “to see the breakdown of the different Asian-Pacific Islander groups because they are very different.”

Filipinos on average perform 15% to 20% lower in proficiency standards in public schools and in college-going rates compared to their East Asian peers, according to a 2022 report from the Tinalak Council, a group that supports Filipinos in education and is based at UH Mānoa’s College of Education.

Filipino Americans comprise the largest ethnic group in Hawai‘i’s public schools, accounting for 24% of the student population, according to the DOE. At Farrington and Waipahu high schools, the student populations are majority Filipino.

For the 2019-2020 school year, Filipinos had a high graduation rate (91%) but low college-going rate (54%), the Tinalak report says, and the number of Filipinos at four-year colleges is disproportionately lower compared to many other ethnic groups in Hawai‘i.

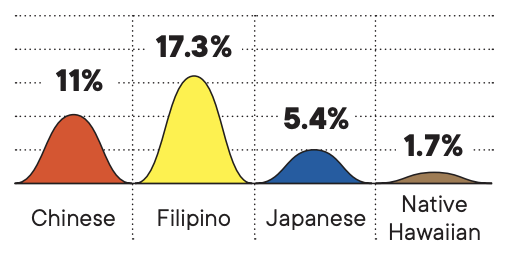

The Pamantasan Council, a UH System organization that seeks to enhance Filipino representation in education, says 14.1% of UH System students are Filipino American. At UH Mānoa, the proportion of Filipino American undergraduate students is 11%. Among graduate students, it’s 5%, and among faculty, it’s 2.5%. Among its 16 deans and interim deans, only one is Filipino American.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s 2022 American Community Survey says 69.5% of people with full or partial Filipino ancestry are in the state’s workforce. For the entire Hawai‘i population, the proportion is 66.8%. Of all Filipino workers, 20.3% work in educational services, health care and social assistance; the arts, entertainment and recreation (19.4%); retail trade (14.1%); and construction (7.6%).

Filipino Student-Led Project Makes Breakthrough

When Halagao’s daughter Marissa was a sophomore in Punahou School, she took an Asian history class that only included Chinese and Japanese history. That provoked her to start what would become the Filipino Curriculum Project.

“I felt that there was a very big oversight,” says Marissa Halagao. “The fact that Filipinos weren’t included, it communicated to me as a Filipino student that my history, my culture, was not worthy to be studied.”

She worked with her teachers to develop a Filipino studies curriculum and contacted students from high schools across the state to inspire others to push for courses that focus on Filipino history.

Raymart Billote, a Waipahu High School graduate and current UH West O‘ahu student, was the first of five students recruited for the project. He immigrated to Hawai‘i in 2017 and says adapting to Hawai‘i was difficult at first.

In his freshman year of high school, he was part of his school’s English language learner program, but transitioned out when he was a sophomore. After that transition, he felt like he did not fit in because he had classes with students who had grown up in Hawai‘i.

“I kind of felt lonely at that time, like I don’t feel like I fit into this group,” says Billote. “That’s when I started to isolate myself because of the language barrier as well.”

It was not until his senior year that Billote was recruited by Marissa Halagao for the Filipino Curriculum Project. Like Halagao, he saw how Filipinos were underrepresented in history books, and he was inspired by her.

Billote says his relatives who were born here don’t speak a Filipino language and don’t know much about their culture.

“Filipino students who were born here, they weren’t given as many opportunities to learn about their heritage,” he says. “In school, they would mention Filipinos, but it’s not as in-depth.”

The Filipino Curriculum Project team has grown to 26 students, spread among eight schools across the state, and includes nine members in college. They spent two years lobbying at the state Legislature and also garnering support for the curriculum from other educators and community members.

Last year, the team hit a milestone: The state Department of Education says Hawai‘i is the first state-wide school district to approve a high school social studies course on Filipino history and culture.

The course, named Filipino History Culture, will be offered at two high schools this fall: Waipahu and Farrington. Billote, who encourages his Filipino classmates to be proud of their heritage, is an education major at UH West O‘ahu and hopes to eventually teach the course.

“I try to bring my culture with me everywhere I go,” says Billote. “In college when I introduce myself as a first-generation immigrant, I’m not ashamed to do that.”

Marissa Halagao, who is now a freshman at Yale University, says it is empowering to learn about people “who look like you” in history books because “how are students supposed to feel validated in themselves if the only people that they learn about, the only role models and people that they look up to have little to no resemblance to them?”

There were 7,065 Filipinos in the UH System in fall 2023, according to the UH Institutional Research, Analysis & Planning Office. Community colleges had 4,370, Mā – noa 1,834, West O‘ahu 668 and Hilo 193.

Advocating for Workers’ Rights

Sergio Alcubilla came to Hawai‘i from the mainland because it reminded him of his family’s upbringing and working-class background.

He was born in the Philippines and has five other siblings. His father, who was in the military, was killed during the People Power Revolution in 1986 that ousted Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos. Alcubilla was only 6 then.

From that point, Alcubilla says his mother, who had been a nurse in the U.S., raised her children on her own.

Alcubilla and his family first emigrated to the mainland from the Philippines but eventually came to Hawai‘i because of its large Filipino community. An early memory of his is of seeing so many working-class Filipinos working in Waikīkī in the hotels and service industry.

Where Filipinos Live in Hawai‘i

He graduated with a bachelor’s in economics and political science from the University of Florida, and received his law degree from UH Mānoa’s Richardson School of Law.

Alcubilla says he felt “this sense of duty – that if I could give back to the community, this would be the best place for us to settle down.”

He talks about “our kababayans,” which means fellow countrymen in Tagalog, “who are working low-wage jobs and two or three additional jobs.” He himself worked late nights at Macy’s to support himself while going to law school.

Now, as executive director of the Hawai‘i Workers Center, he advocates to ensure workers are paid living wages, have rights and are treated equally.

“From our own personal experiences, we just know how hard it is to try to raise a family, to try to make ends meet and really fulfill that immigrant dream.”

In 2015, then-Gov. David Ige signed legislation declaring Dec. 20 as Sakada Day to honor the more than 100,000 Filipinos who were brought in to work on Hawai‘i’s plantations during the 20th century. The bill recognized the sakadas’ and the overall Filipino community’s contributions to Hawai‘i.

Young Entrepreneurs Embrace Their Culture

In 2021, Lalaine Ignao and Eric Ganding launched a boba-shop food truck as an homage to their Filipino roots and to honor Ignao’s late grandmother. It is called “Sama Sama,” which translates to “togetherness” in Tagalog.

Lalaine Ignao and Eric Ganding, owners of Sama Sama, a food truck serving drinks inspired by Filipino flavors.

The idea took seed while Ignao was growing up in Washington state: Her family would frequent a Chinese restaurant there and then go to the boba shop next door for dessert.

Sama Sama’s menu has Filipino-inspired drinks flavored by ube, leche flan, buko pandan, sampaguita and turon. Ignao says their food truck appears at various events and locations across O‘ahu, including at UH Mānoa. They opened a physical storefront in Leeward Community College’s library in 2023.

Ignao points to ingredient shortages and increasing costs as some of their early challenges. And Ganding says the pair encountered people who were skeptical of their plan to open a boba shop.

“People thought that we were just going into it as just something on the side,” he says. Instead, they jumped in fully. Today, the couple aims to break the belief that Filipinos need to be in health care or engineering to succeed.

“I think society has made it seem like success is about money and material things,” says Ignao. “But I think at the end of the day, success is what your definition is.”

Filipino Americans make up the third-largest Asian ethnic group in America, following Chinese and Indian Americans, according to the 2020 U.S. census. With a population of more than 4.2 million, Filipino Americans make up about 18% of the total Asian American population in the U.S.

Language Access for All

Agnes Malate couldn’t speak English when she emigrated from the Philippines at age 7. The only words and phrases she knew were yes, no, thank you and what is your name.

Malate grew up in a farming family and remembers living in a bamboo house in the Philippines. Her father worked on a Waipahu sugar plantation when they came to Hawai‘i.

Determined to have a better life, Malate says, she learned English by reading books. She values education because it was “transformative” for her and “provides for more resources and opportunity.” Malate is currently director of the Health Careers Opportunity program at UH Mānoa, which recruits and mentors students in health-related careers.

Malate is also a language-access advocate and helps her family and others get important information and news in their native language.

During the Covid pandemic, she says, “there wasn’t really a mobile, collaborative, unified response” to help the Filipino community get access to health resources.

Filipinos had the highest Covid mortality rate in the Islands, behind Pacific Islanders, according to the state Department of Health. As of April 18, 2022, Filipinos represented 24% of Covid deaths in Hawai‘i.

The impact of Covid on Filipinos spurred Malate, civil rights activist Amy Agbayani and May Rose Dela Cruz to establish FilCom Cares, a project part of the Filipino Community Center that provides Filipinos in Hawai‘i with outreach, education, and access to resources such as vaccinations and testing.

About 59% of those people in the state with pure Filipino ancestry do not speak English at home, according to a 2016 report on non-English speakers in Hawai‘i by the Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism.

In the U.S., not being proficient in English can lead to miscommunication and hesitancy, Malate says. She describes a time when she had to accompany her parents to their doctors’ appointments to translate because the medical terms often “were too hard for them to understand.”

When she volunteered at vaccination clinics during the Covid pandemic, Malate says, people expressed their thanks. “Just having familiar faces doing the vaccinations gave them confidence and trust,” she says.

Malate is president of Ethnic Education Hawai‘i, a local nonprofit aiming to make “communications accessible for all” through different media.

English Proficiency

Proportion of these ethnic populations in Hawai‘i who say they speak English less than very well:

Home Language

Proportion of these ethnic populations in Hawai‘i who say they speak a language other than English at home:

One of those is KNDI 1270 AM Radio, a source of news and entertainment for underserved communities. The station broadcasts in 13 languages: English, Chinese, Chuukese, Laotian, Marshallese, Okinawan, Pohnpeian, Samoan, Spanish, Tongan, Vietnamese, Ilocano and Tagalog.

Longtime KNDI radio host Larry Ordonez, who has spent more than 40 years working in media, says he feels like he “helped elevate ethnic radio broadcasts beyond the norm studio setting.”

In 2017, he became the station’s first on-air host to do remote broadcasts from his home studio. So when the pandemic hit, he was ready to help the Filipino community.

Ordonez does his “Filipino Radio” program on Sundays and Mondays, and broadcasts news in English, Ilocano and Tagalog. During the pandemic he partnered with Filcom Cares to broadcast Covid health information to his listeners.

During 2020 and 2021, each of his programs generated an average of about 3,000 to 4,000 listeners.

“Ethnic radio fills the gap unmet by mainstream media in reaching out to the underserved,” says Ordonez.

Having an outlet to listen to music or news in an individual’s native language is important because people can understand the content and “it gives them that connection to their upbringing,” Ordonez says.

Most of the Filipinos who have come to Hawai‘i are Ilocano, from the northern region of the Philippines, according to the state Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism.

A Resilient Community in Time of Need

The fire last year that destroyed Lahaina and killed 100 people heightened the struggles of the Filipino community, which made up about 40% of the town’s population.

Local Filipino leaders and community members sprang into action to aid the population. “We’re working tirelessly to help Maui recover and rebuild,” says Butay, the state Department of Labor and Industrial Relations director.

Butay says he has been going to Maui at least once a week to meet with staff and help those affected. His department has also been offering unemployment insurance and temporary jobs to affected workers.

The Hawai‘i Workers Center has been pushing for a “just and equitable recovery for all workers” on Maui, says Alcubilla, the executive director. At an outreach event on Maui, he said that a lot of Filipino families he spoke with said they were denied FEMA assistance.

“For a lot of the Filipino community, they just see that letter that says denial and then they just stop it and they don’t push it further,” he says. “We understand that it’s a denial letter, but it doesn’t mean you’re not qualified for it.”

Alcubilla stresses that the community should take advantage of available resources and ask for help when needed.

Malate and the FilCom Cares team arranged for volunteers to assist the public at resource fairs by translating important information like how to apply for unemployment benefits, and where to get replacements for lost documents and find housing assistance.

When radio host Ordonez heard about the fires, he says he was devastated. He grew up in Lahaina after immigrating to Hawai‘i, and two houses that his family once lived in were among those destroyed.

“A lot of my friends that I went to high school with and friends and neighbors with houses in the area – they’re all gone,” says Ordonez.

He used his radio show to help those affected. “Even though there was no power, phone service or internet at that time, we have radio and people still have some cars,” he says.

“Some of them can listen. We will ask them to tell their friends about resources that they can tap to help them.”

Butay says Filipinos are “just as important as any other ethnicity or race” and will continue to rebuild.

“We play an integral role in the state’s economy, culture and society. We’re symbols of immigrant achievement,” he says. “Without the Filipinos, the hotels, the construction, restaurants, health care and other industries wouldn’t be able to survive.”