Pedal Power

Will Mather has bike renting down to a science. He’s able to fit a customer with the right size bike, discuss safety and road rules, equip them with a helmet and lock, and take payment for the rental, all in about seven minutes.

Mather is the store manager of The Bike Shop Kailua. In the past two years, bike rentals, particularly with Japanese tourists, have burgeoned in the Windward town. And The Bike Shop Kailua is one of the most popular rental outlets, especially after it moved three blocks to Kailua Road this past May.

The mission of the Hawaii Bicycling League is to enable more people to ride bicycles for health, recreation and transportation. Some of its leaders are, from left, Malia Harunaga, adult education manager; Hannah Neagle, Leeward bikeway outreach coordinator; Daniel Alexander, advocacy director; and Travis Counsell, events director. Photography by Aaron K. Yoshino.

“We know the perks of cycling,” says Mather, who bicycles to the store from his home in Honolulu. “It’s associated with lower costs and exercise, but there’s the added freedom, the beauty of riding. For us, as a bike shop, we want to stress the responsibility that comes with that.”

It’s not just tourists pushing the pedal. For decades, bicycling has flourished in communities like Kailua and Haleiwa thanks to grassroots support, including mothers advocating for safe routes to and from school, and surfers looking for easier access to their favorite beaches. But the state as a whole, particularly Oahu, is becoming more bike friendly, part of a national trend. According to the League of American Bicyclists, the number of bicycling-friendly communities like Kailua has increased 105 percent from 2000 to 2013 nationally, and bicycle usage has gone up 46 percent nationwide.

In the past two years, Honolulu built its first protected bike lane down King Street – now the most used bike lane on Oahu – added bike lanes along parts of Waialae Avenue and hired an administrator to oversee the city’s complete streets project, which requires that public streets serve all transportation needs. 2017 is on track to keep pace.

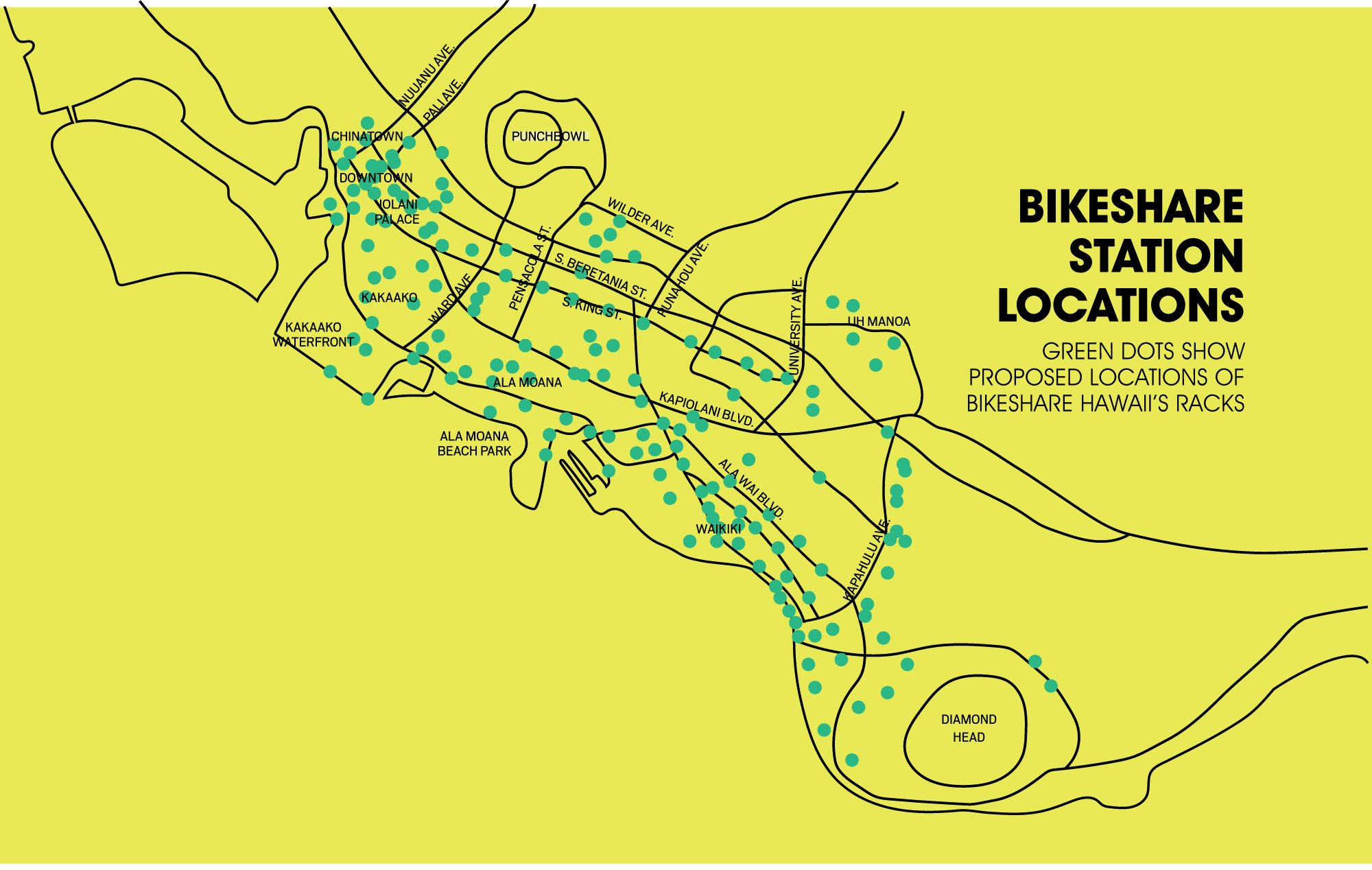

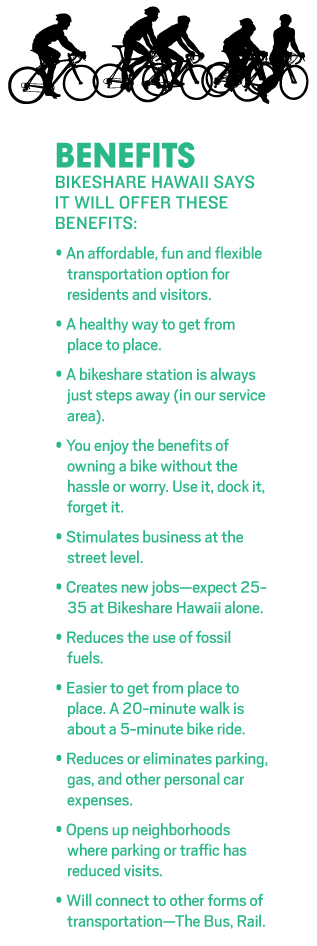

This summer, Oahu will join dozens of Mainland cities by launching Bikeshare Hawaii, a community bike rental network. Proponents say bicycling offers more than improved health and increased sales for bike shops – they say it also improves traffic and benefits stores and restaurants that are not in the cycling business.

TOURISM ON TWO WHEELS

TOURISM ON TWO WHEELS

About 30 white, green and orange cruisers gleam in the mid-morning sun. The rest of the 60-plus bike fleet is already roving Kailua’s streets, operated mostly by Japanese tourists, and it wasn’t even noon. A Japanese couple steady themselves on their colorful cruisers, then pedal out of the parking lot.

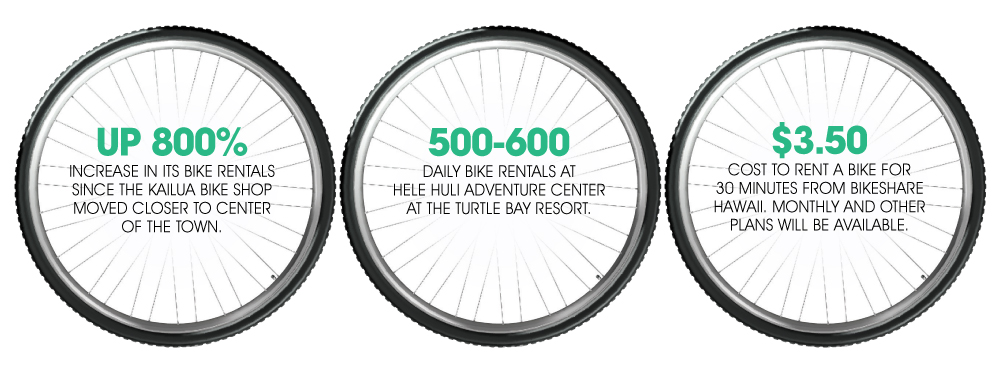

The rows of bikes are one of the first things you see after crossing the bridge into Kailua town. That’s intentional, says Mather, who notes The Bike Shop Kailua’s prime location and outside space were the top reasons why the shop moved there. Mather says rentals have increased 800 percent since they relocated, though sales and repairs remain the majority of the shop’s business.

Kailua has become a must-visit for Japanese tourists during their Oahu vacations, and many arrive by tour bus for the day. Bikes are an easy and cost-effective way to explore the community’s shops, restaurants, beaches and neighborhoods. Mather says his store hired a Japanese-speaking employee and provides Japanese-language pamphlets with Hawaii road rules and bike safety.

Tourists can choose from several rental shops in Kailua. With all the bikes now on Kailua’s streets, local drivers have learned to be more vigilant of cycling tourists, who sometimes seem oblivious to the cars. But Mather says the shop is only aware of three significant incidents involving cyclists renting its bikes: improper street riding, locking a bike in the wrong place and, once last fall, some Japanese visitors had their bags stolen from their rentals. “The thing for us is to communicate with the customers coming in. Where are they coming from, what are they visiting for, how can we help facilitate that,” says Mather, adding that the bike shop gives visitors directions, makes suggestions and promotes locally owned businesses.

Among the most popular destinations for the cyclists, says Mather, are Kailua’s beaches and the 3-mile Lanikai Loop. But time in town is just as important. Mather says he’s heard anecdotally from Kailua restaurants and boutique owners that the self-guided, two-wheeled tours of the town have improved sales. He says visitors can save more money by renting a bike instead of a car – rentals are $15 for four hours – and spend more time and money shopping and dining, instead of searching for parking.

“With bikes, they can get around more quickly. Who’s to say it’s not the difference between a $30 sale and a $150 sale?” he says.

Thirty-four miles away, in Kahuku, Brett Lee has had similar success. Lee is the owner of Hele Huli Adventure Center at the Turtle Bay Resort. The one-stop center offers bike, moped, Segway and snorkel rentals as well as guided tours.

“Bike rentals have rocketed up to the No. 2 spot in overall revenue for my company,” says Lee, who started Hele Huli in 2009. He estimates that 500 to 600 people, most of them hotel guests, rent bikes from the center each month.

To meet demand, the resort opened a 3-mile mountain-bike trail in 2015, and plans to add three more miles. “There exists 12 miles of multi-purpose trails already, but it’s much more appealing to people when there’s a specific trail system for bikes only,” says Lee, adding that the center has also hosted racing events for kamaaina.

Lee says he also gets visitors, nearly daily, who rent his bikes to ride off-campus for lunch at one of Kahuku’s famous shrimp trucks, or to visit the North Shore’s renowned surf breaks. “Bikes allow them to make that trek and explore (the North Shore) in more intimate fashion,” he says. “Unlike in a car, you can take in all the sounds, smells. Your senses are more stimulated.”

SHARING BIKES

SHARING BIKES

Lori McCarney has rented bikes in cities across the country and understands the thrill cyclists get exploring new places. The longtime executive and triathlete is the CEO of Bikeshare Hawaii, a nonprofit founded in October 2014 and slated to launch this summer. Bikeshare will be a network where riders can check out bikes at one solar-powered docking station and then check them back into another station several blocks away. “It’s sort of like personalized mass transit,” she says. “Bikes are bringing people back to the street.”

Bike-share networks have been successful across the Mainland, including in Portland, Chicago, New York and Washington, D.C. The programs provide increased access to bikes, without the cost of ownership or the burden of storage for apartment dwellers. In large cities, bike shares are often combined with walking, taking the bus or driving. McCarney says she wants Bikeshare Hawaii to be another transportation option among the Island’s existing options. It will cost $3.50 for 30 minutes, or $20 for 300 minutes that can be used in increments; monthly plans will range from $15 to $25.

Such programs have taken off elsewhere: New York City’s Citi Bike logged 10 million rides in 2015; Chicago’s Divvy had 3.2 million rides, with annual memberships costing $99 ($5 to low-income residents).

McCarney predicts good things for Oahu’s program. The nonprofit conducted market research, she says, and “unlike other cities, we have all five factors that make for a successful bike share system.” They are good weather, flat terrain, urban density, government support and a tourism market.

She also expects the majority of Oahu’s users will be visitors. “Visitors have a different price elasticity than residents,” says McCarney. “As a resident, you aren’t going to pay the same amount of money for a functional transportation as for a pleasure trip.”

McCarney says the program will do more than provide alternative transportation. “I think bike share might be a solution to parking,” she says. For example, she says, the Chinatown Neighborhood Board is excited by Bikeshare’s launch as a way to help alleviate the area’s parking challenges.

In April to May, the organization plans to flood urban Honolulu with 1,000 to 1,200 bikes. There will be a bike station holding about 10 bikes every two to three blocks along main arteries like Kalakaua Avenue, King Street and Beretania Street, from River Street to Diamond Head. The organization has received $1 million from the city and $1 million from the state, as well as grants from Howard Hughes Corp., the Hawaiian Electric Industries Charitable Foundation and others.

McCarney says the nonprofit is approaching community organizations and businesses about station locations and, once they’re installed, hopes to form promotions to support surrounding businesses. “It’ll only be useful for you if it works in a lot of situations,” she says.

Dave Newman thinks Bikeshare Hawaii might be good for his business. Newman owns Pint + Jigger, on South King Street near McCully. The gastropub sits toward the end of the 2-mile King Street protected bike lane. Newman says when the bike path first opened, there was grumbling from neighboring businesses about traffic congestion, but he says cyclists and drivers have since more or less figured out the bike lane. (City data shows the bike lane has increased the time it takes to drive down King Street by an average of 30 seconds.) Newman says since the bike path opened two years ago, he now gets regulars who arrive at the bar via bike, especially during its brunch hours.

“We have increased visibility. It’s hard to see Pint + Jigger coming down King because of that tall apartment building,” he says. “We’ve had people come in who said they saw us when they were riding down the bike lane in the other direction. So now people can see us on King.”

Newman says he’d be open to having a Bikeshare Hawaii station in front of the bar. “Alternative transportation is going to get more popular,” he says. “The weather is nice, so why wouldn’t you want to rent a bike and cruise around town?”

SAFETY FIRST

Given the pleasant weather, flat landscape and urban density, many Oahu residents want to ride bikes. Since the city debuted the King Street protected bike path in December 2014, ridership on the Honolulu street has increased 78 percent, according to its ongoing ridership studies.

Today, the 2-mile bike path, from Alapai Street to Isenberg Street, is Oahu’s most traversed bikeway. (There are 61 U.S. cities that have protected bike lanes.) Riders and advocates say that’s likely because the lane has an asphalt berm and short plastic posts that physically separate cyclists from motorists. A 2016 report by the National Association of City Transportation Officials says 60 percent of Americans are interested in biking but are concerned about safety. Of those respondents, 81 percent said they would ride on a street with a separated bike lane.

Mark Garrity, acting director of the city Department of Transportation Services, says the city doesn’t want the King Street project to be a one-off. “We understand that King Street (bike lane) by itself may have helped a few people, especially those people commuting between downtown and the university area,” he says. “But for it to be effective and for people to make up their minds that they want to use bicycles on a regular basis, we need to create a network of protected streets.” To do this, he says, the city is looking to create a line item in the upcoming budget specifically for bike lane projects. (Bike lane projects currently come out of the existing transportation budget; the King Street project was about $500,000.) Garrity adds the city is designing traditional bike lanes for South and McCully streets, to connect with the King Street lane, and is eyeing Ward Avenue, Pensacola Street, Piikoi Street and Queen Street for future projects.

Robert Moses welcomes the new infrastructure. The Realtor has been riding bicycles recreationally for 50 years, and commuting via bike for the past year. And three times a week, he and his wife, Genie, bike from their condo in Century Center to Kapiolani Park and back, using the Date Street and Kapahulu Avenue bike paths. Safety is a top concern, especially when cycling in traffic. Before hopping on his bike, Moses straps on his helmet, knee and elbow pads, and a safety vest. His bike is also equipped with a headlight and taillight.

“I think the simplest way to improve safety is to build more protected bike lanes,” he says, adding, “safe places to park bikes are not universal.”

The city has installed about 450 bike racks, which don’t include bike racks on private property that are available to the public, says city spokesman Jesse Broder Van Dyke. Most of the racks are located in urban Honolulu and Waikiki; Kailua has 19, but Oahu’s Leeward side only has one city-installed rack, which is in Kapolei, according to city data. Residents can request that a bike rack be installed in specific city-owned public locations, by calling or emailing the Honolulu Bicycle Program coordinator: 768-8335 and csayers@honolulu.gov.

“We want our roads to be accessible for all, safe for all,” says Daniel Alexander. For the past two and a half years, Alexander’s job has been to make cyclists feel safer. He is the advocacy, planning and communications director of the Hawaii Bicycling League, working with advocates, the community, developers and Hawaii’s governments to help implement bicycling policies and infrastructure across Oahu. In 2015, the Hawaii Bicycling League debuted the Minimum Grid HNL project, which supports the creation of a network of protected bikeways within a half-mile of everyone in urban Honolulu and within one mile of everyone in urbanized Oahu. The goal is to have 20 miles of protected bike lanes on the Island by 2020. “When we talk to people, people want to be able to bike. It’s a big desire, but the fact is they don’t feel safe on a lot of our roads,” he says.

The math is simple, he says. An increase in bike infrastructure results in more riders. He says studies have shown that the upswing in cyclists leads to better awareness and safety for both cyclists and motorists, and increases road capacity as fewer people drive.

“I think as we start building more infrastructure and build a network where people can get from their house to the store, from their house to work, or their hotel to their destination, then a lot more people will adopt cycling,” he says.

BEHIND THE SCENES

Ride along with the Hawaii Bicycling League in this video captured in December as part of our photo shoot for this story.