You Are What You Surf

Last fall, Cliff Kapono could be found surfing waves off the coasts of Ireland, Spain, Britain and Morocco. After a brief stop home in Hilo this January, he planned to head south to Chile and then west to Indonesia. Kapono’s global itinerary isn’t your typical surf trip: it’s part of the Surfer Biome Project, a scientific effort to understand surfing on a molecular level.

If molecules sound like an odd thing for a surfer to think about while getting barreled, it shouldn’t be, says Kapono, a doctoral candidate in chemistry at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). A surfer’s interaction with the ocean goes well beyond the waves he or she catches. After all, our bodies are really just a collection of cells. Some of those cells belong to microbes and other microorganisms that are crucial to our survival. The moment a surfer steps into the water to paddle out, those microbes, as well as the chemical molecules that make up things like sunscreen or surf wax, begin to interact with the equally microscopic marine life that exists in the ocean, which gloms onto the surfer, unseen and, most of the time, unfelt.

Cliff Kapono says his research aims to show how surfers, in small ways, change the ocean they swim in, and the ocean changes them. Photo by Joseph Schumacher.

These exchanges, Kapono says, take place via what he calls a “sophisticated song of chemicals.”

“Everything on Earth can, and does communicate, through chemistry,” he says. That includes humans, though we’re often not aware of it. “Just by washing your hands, you’re changing the chemistry of your environment.” On a very small scale, then, a surfer’s diet and behavior change the chemical makeup of the ocean – and vice versa.

It’s this exchange that the Surfer Biome Project hopes to document. At each of his far-flung destinations, Kapono distributes a DIY kit developed by the American Gut Project, a crowd-sourced effort to better understand the microbes that aid human digestion. Surfers use the kits to collect microbial samples from their mouths, nostrils, hands, chests, navels and surfboards. Kapono analyzes those samples (along with a supplied fecal sample) and compiles them into a microbial profile, or microbiome, for each surfer.

Each surfer is then plotted on a graph according to his or her chemical makeup. Because ocean bacteria likely vary by continent and region, Kapono expects Hawaii’s surfers to be similar in their molecular makeup and cluster together on the graph. The same with surfers in Spain, and those in Indonesia. Identifying differences between populations can help researchers isolate behaviors or bacteria that affect human health, says Kapono, whose research is funded by UCSD’s Global Health Institute. “We have to first identify the differences, and then we can begin to ask the question, Why are things happening the way they are happening?” he says. “Looking at the microbial world is just a new way of asking questions.”

Using the American Gut Project’s database, Kapono will also be able to compare surfers to nonsurfers, which could provide new insights into the interrelationship between ocean and human health. “We’re one of the few global populations that step between these two worlds: terrestrial and marine,” he says. “It’s a population that’s almost amphibious in nature.”

Anne Leonard, a postdoctoral researcher at the European Centre for Environment and Human Health at the University of Exeter Medical School in England, says this “amphibious” quality makes surfers a demographic worth studying. “They’re an indicator species, as it were, of the hazards, and maybe the benefits, of going into the marine environment,” Leonard says.

Those hazards seem to be increasing.

Kapono is from Hawaii Island and is a Ph.D. candidate in chemistry at the University of California at San Diego. Photo by Joseph Schumacher.

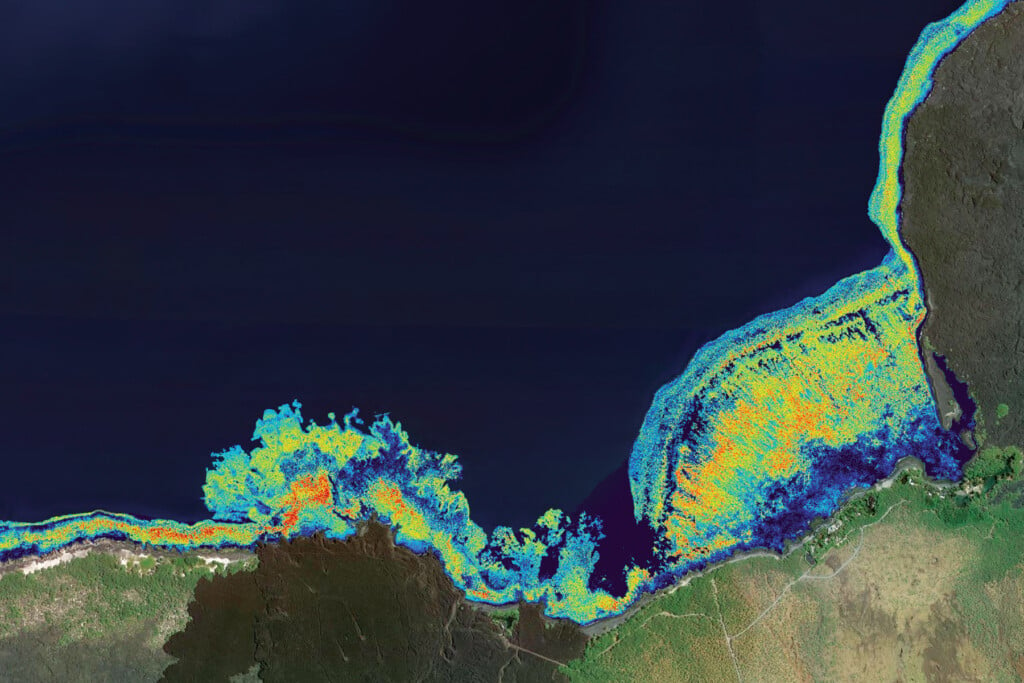

A 2008 study published in the journal Environmental Health examined the link between oceans and public health, including risks associated with certain microbes, chemical pollutants and harmful algal blooms, which can be caused by nutrient loading associated with industrial agriculture and which, according to the EPA, are increasing in both frequency and intensity. Many health risks, the study noted, may be exacerbated by global climate change, and populations “such as islanders and coastal groups that depend heavily on local marine resources may be particularly vulnerable to health effects from this kind of change.”

Many in Hawaii have seen these changes firsthand. “When I was younger, if I had a cut, or I had a cold, I went to the ocean because I knew it would heal it,” says Stuart Coleman, who grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, but is now the Hawaii regional director of the Surfrider Foundation and an avid surfer. “Now, I don’t go near the ocean if I’ve got an open cut or a cold because I know it can go the other way.”

Because of their intimate connection to the marine world, surfers historically have been active in raising awareness about issues that affect ocean health. The Surfrider Foundation was founded in Malibu, California, in the early 1980s, by three surfers who worried that encroaching development was poisoning the ocean. Since then, the grassroots organization has grown into a national nonprofit with more than 80 chapters, and its mission has gone from saving one surf break to protecting the country’s coastal areas.

Around the same time, a similar story was playing out in St. Agnes, England. A small group of surfers rallied around issues of water quality, eventually forming Surfers Against Sewage, a nonprofit that operates throughout the United Kingdom. The organization now often partners with Leonard and the European Centre for Environment and Human Health, which hosted Kapono during his time in Cornwall, England. (Leonard has her own surf-related research project, the cheekily titled “Beach Bums,” which is analyzing data from surfer-submitted rectal swabs to investigate the health effects of specific kinds of ocean pollution.)

Kapono says the partnerships that Surfers Against Sewage has formed with the university and local businesses, including surf and apparel company Finisterre (“a European Patagonia,” he says), have been effective in engaging people on issues like beach litter and toxic chemicals. He would like to see the model replicated in Hawaii.

“How do we work with the universities, the experts that are really understanding the science?” he says. “How do we get the nonprofits that are able to galvanize the community and talk to policy makers? And how do we get the brands to push resources into these avenues of environmentalism and human health?”

On a more personal level, Kapono sees his research as a pathway into the Hawaiian moolelo (stories) he grew up hearing. Kapono was raised in what he describes as a strong Native Hawaiian community that taught him traditional ways of thought. For years, this cultural education ran parallel to his studies in school, never intersecting. “I was always going between these worlds of Western science and traditional Hawaiian science, and eventually I was like, I’m just gonna take it all as one thing.”

If this sort of willful integration ran the risk of leaving Kapono straddling an unbridgeable divide, his experience has been that the two traditions are more similar than most people think. The chemical interactions he’s studying are the ancient stories, he says. “When we say we talk to the rocks and trees and birds, we’re not using English, or Hawaiian, we’re not even using our voice a lot of the time. We’re communicating with chemistry.” Western science, in other words, is slowly beginning to demonstrate what many Hawaiians have long believed: that human beings are inseparable from their surroundings – surfers perhaps most of all.