Cesspools Are Killing Hawai‘i’s Coral – But It Doesn’t Have to Be That Way

An expert explains how to reverse the damage from the state’s 83,000 cesspools, including using treated wastewater for irrigation and landscaping.

Here are a few facts you won’t find in any travel guide about Hawai‘i: There are 83,000 cesspools across the state, and these substandard systems discharge an average of 52 million gallons of untreated sewage per day into the ground and groundwater. That’s like a massive sewage spill every day.

In fact, Hawai‘i has more cesspools per capita than any other state and it was the last state to ban them, by more than three decades.

The toxic stew of poo, pee, pharmaceuticals and other contaminants sent into the ground, seeps into the groundwater and often ends up in the ocean, where it harms nearshore coral and can sicken swimmers.

In recent years, a coalition of scientists, citizens and environmental groups set out to change sanitation policies and create public awareness. The state Legislature passed several laws to reduce sewage pollution: Act 120 banned the construction of new cesspools (2016); Act 125 mandated the conversion of all cesspools to approved sanitation systems by 2050 (2017); and Act 132 created the Cesspool Conversion Working Group (2018).

It seemed like progress was being made. After four years of meetings, the working group submitted its final report to the Legislature in 2022 about the best ways to convert cesspools and find funding to help homeowners with the high cost of conversion. An omnibus bill, HB 1396, supported several of the group’s recommendations and different versions were passed by the House and Senate, but the measure died in conference committee behind closed doors.

“Disappointed is an understatement, let me put it that way,” Sen. Mike Gabbard, chair of the Senate Agriculture and Environment Committee, told Civil Beat in August. “Lots of different people … put their heart and their soul into this thing. It’s not like this is a manini thing. It’s a huge problem we have, and it’s affecting all of us.”

Gabbard said advocates would try again next year to pass the bill.

To understand the problem requires a deep dive, and while the ocean may look clear and blue from a distance, new research into land-based sources of pollution makes it clear that all is not well in the coral kingdom.

The Problems With Cesspools

Cesspools are basically holes in the ground, and their untreated sewage seeps into our groundwater, streams, fishponds and nearshore areas. That pollution contains many harmful waterborne pathogens that can cause gastrointestinal illnesses whose symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, stomachache, and fever in humans.

Sewage-related pathogens in our groundwater can also contaminate drinking water sources. One Department of Health study revealed that 50% of the samples from private drinking-water wells in Hawaiian Paradise Park on Hawai‘i Island showed signs of fecal indicator bacteria.

A 2018 DOH study found elevated rates of nitrogen in the Upcountry Maui groundwater, and this can lead to illnesses like “blue baby syndrome,” a potentially fatal reduction in blood oxygen in infants. EPA and academic studies have revealed links between higher levels of nitrogen from cesspools and elevated rates of bladder and other cancers.

Long Island, New York, is the only place with more cesspools than Hawai‘i and the resulting contamination has led to costly and harmful algal blooms, massive fish kills and the collapse of the area’s shellfish industry.

A groundbreaking paper just published in the scientific journal Nature suggests that increasing land-based sources of pollution and decreasing herbivore fish populations are two of the biggest stressors on the survival of Hawai‘i’s reefs, especially during and after coral bleaching events.

The land-based sources of pollution mainly consist of stormwater runoff, sedimentation and the nutrient loading of nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture and wastewater pollution. Together, they wreak havoc on Hawai‘i’s nearshore ecosystems and coral reefs. This is especially concerning because current El Niño conditions could cause another massive coral bleaching event like the one in 2014-2015, when Hawai‘i lost more than 25% of the area that living coral reefs previously covered.

One piece of good news is a new program called ‘Āko‘ako‘a, which means both “coral” and “to assemble” in the Hawaiian language. The program focuses on restoring corals along the 120 miles of reefs off the west coast of Hawai‘i Island. Funding for this ambitious undertaking comes from Arizona State University, the Dorrance Family Foundation, the state Division of Aquatic Resources and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The $25 million initiative is led by Greg Asner, director of Arizona State’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science. Asner is also on the faculty of ASU’s School of Ocean Futures and has helped the university make a big splash in Hawai‘i.

Along with that, Asner is a senior author of the new Nature paper and the managing director of the Allen Coral Atlas, an online map of all the world’s coral reefs. Armed with decades of research, he is now in the process of assembling and coordinating a team of coral reef restorers.

A former deep-sea diver with the U.S. Navy, Asner is based on Hawai‘i Island and has spent much of his life monitoring coral reefs from air, land and sea. Since 1998, he and his team at the Global Airborne Observatory have used planes, satellites and high-tech instruments to monitor and diagnose damage to reefs. It’s a daunting task, especially with the cascading threats from climate change, rising temperatures, overdevelopment of coastal areas and land-based sources of pollution.

Greg Asner leads a $25 million initiative to restore corals along 120 miles of reefs off the west coast of Hawai‘i Island. | Photo: courtesy of Greg Asner/Arizona State University

Flying along the coastline in his highly modified twin-turbo prop aircraft, Asner can see huge patches of macro algae growing off West Hawai‘i’s coast. In contrast to the harmful algal blooms that grow on the water’s surface off Florida, this kind of algae grows on the seafloor, fueled by excessive nutrients from agricultural runoff and wastewater. And the rapidly spreading invasive macro algae is seriously damaging the coral reefs off West Hawai‘i.

“What we know about wastewater is that it increases nitrate concentrations in seawater, and that nitrate stimulates the growth of macro algae,” Asner says. This creates a vicious cycle when combined with overfishing and decreasing populations of herbivore fish that normally eat the algae. Without enough herbivore fish to eat them, the seaweeds grow until they smother the reefs. And with the added stressors of marine heat waves and the chronic cocktail of nutrients, Hawai‘i’s reefs are more prone to coral bleaching and collapse.

The Value of Coral Reefs

Known as the rainforests of the sea, coral reefs are beautifully complex ecosystems. A quarter of all known ocean species inhabit these coral kingdoms, yet they only cover 1% of the ocean. They are extremely valuable in providing food, jobs and recreational income, and they help to protect coastal areas against storms, flooding and rising sea levels. A report by the U.S. Geological Survey estimates Hawai‘i’s coral reefs are worth more than $863 million a year.

Culturally, they are priceless. In the Kumulipo, Hawai‘i’s creation chant, the coral polyp, or ko‘a, is the first organism created and one of the key building blocks for all forms of life in the Islands. “These reefs are fundamental to the cultural identity of Hawai‘i,” says Asner. “They are literally linked through generations of cultural identity.”

Cultural engagement and leadership are key parts of the ‘Āko‘ako‘a program. Asner has been working with such Native Hawaiian leaders as Cindi Punihaole, director of the Kahalu‘u Bay Education Center on Hawai‘i Island, on blending modern science and ancient Indigenous wisdom. “We can combine kilo (sustained and careful environmental observation) with experimental science,” Punihaole says, “to develop innovative ways to preserve and restore precious ecosystems and share findings with other sites throughout the Pacific and beyond.”

With its shallow, protected coral reef, Kahalu‘u Bay acts as a marine nursery for corals and fish that can replenish other fisheries along the coastline. “Unfortunately, the safe and shallow nature of Kahalu‘u Bay is also one of its biggest threats,” Punihaole says. “Over the last several decades, the natural and cultural resources of the park have been degraded by an increase in several chronic stressors, including the unmanaged impact of poor water quality from nearby cesspools and increased runoff from development.”

From his airborne lab, Asner sees the damage to the coral reefs along the Kailua-Kona coastline. “There are very large areas of severe macro algae, and those tend to be more common near these areas of development,” he says. “The macro algal cover along Ali‘i Drive in Kona is pretty bad. But when we get to Kahalu‘u, it lights up on our screens with macro algal cover.”

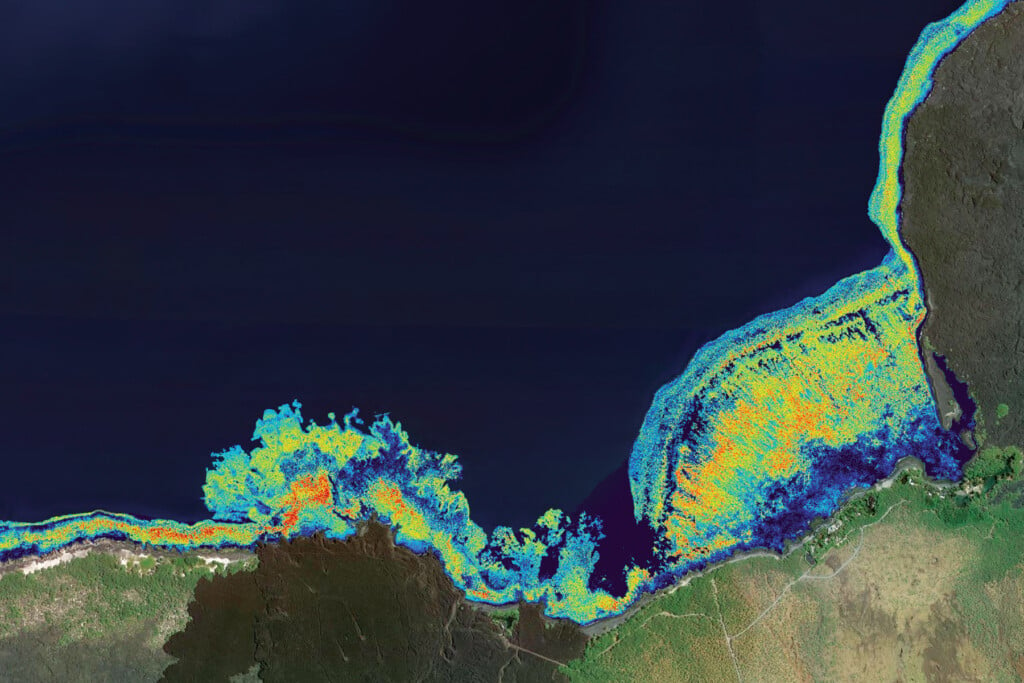

Global Airborne Observatory’s map shows the percentage of live coral cover at Mā‘alaea Bay on Maui in 2019. | Coral Map: courtesy of hawaiicoral.org

The ‘Āko‘ako‘a program has the funding for reef restoration work, but Asner says his team has to be careful about where it focuses its efforts. “When it comes to reef restoration, $25 million sounds like a lot of money, but we have to be practical. There are areas of reef that have declined so far that the framework, the carbonate framework that makes a reef have structure, is failing. As the leader of ‘Āko‘ako‘a, it would be unwise to put all of my eggs in areas where the outcome is likely to be unsuccessful.”

Asner says the program will prioritize its efforts and funding for coral reef restoration on areas that would be graded as “B’s and C’s” on a report card. “For the areas that are D’s and F’s, we cannot put a lot into them,” he says.

He mentions the community of Puakō, which has wrestled with wastewater pollution from cesspools and other individual wastewater systems for decades. The area was once home to pristine corals, but now Asner says its reefs are in the D to F category. “It has really declined,” he says. “There’s a data set that shows in 1970, when I was 2 years old, the reef had around 70% coral cover, and now it’s somewhere around 7%.”

The challenge is how to improve these hot spots of coral decline and find ways to reduce the nutrient loading from cesspools and septic systems, as well as sedimentation from stormwater runoff and rapidly growing residential and commercial developments.

Hot Spots

Mā‘alaea Bay on Maui is another area where the coral reef cover has declined dramatically over the last 50 years. Peter Cannon, a fifth-generation kama‘āina, recalls swimming in the bay as a boy. He says it was like diving into an aquarium with brightly colored corals and fish swimming all around him. But those tropical fish and pristine reefs faded from sight as large condo buildings sprang up along the coast.

The partially treated wastewater from the condo systems was pumped into injection wells and eventually percolated into the bay through underground springs. Nutrients from the wastewater and sediments from stormwater runoff gradually led to a deterioration of water quality and a near collapse of the coral reef system. Now, Cannon says, “It’s a dead zone.” According to the EPA, Mā‘alaea is one of 34 “impaired bodies” of water across the state.

Not ready to give up on his beloved bay and reefs, Cannon has gathered a team to fight for better wastewater treatment. The Mā‘alaea team has developed plans for a decentralized treatment system that will produce high quality water and biochar to be used for irrigation and landscaping. The coalition is currently working with Maui County and Mayor Richard Bissen’s administration to create the proposed Mā‘alaea Regional Wastewater Reclamation System. The plant would reuse all of the liquids and solids and be a model of wastewater recycling for the rest of the state.

Despite declines in Puakō, Mā‘alaea and other areas, Asner says, “The good news is that in Hawai‘i, especially on the Big Island, we have lots of hot spots of high quality reef left.” He refers to these areas as “reference reefs,” where the coral cover is up to 80%-95%. “Those are our biological arks at this point. They are holding most of the biodiversity for the West Hawai‘i reef system.”

In Asner’s home community of Miloli‘i, rapid development is transforming the landscape and creating hazards for the area’s corals and the newly established Community Based Subsistence Fishing Area. About 200 homes have been built in this remote community on the South Kona coast, and 700 more lots could be developed in the coming decade. The area has a number of cesspools, but most of the homes there have traditional septic systems embedded in lava rock. Unfortunately, these traditional individual wastewater systems don’t provide enough treatment or denitrification to protect the reefs.

One solution being discussed in Miloli‘i is to connect the homes to a Pressurized Liquid Only Sewer system. The PreLOS model includes a small collection tank at each home that pumps liquid wastewater through small PVC pipes that are buried 1-2 feet beneath the surface. These pipes convey the effluent to a decentralized treatment facility that can produce clean, recycled water, which is desperately needed in dry areas like Miloli‘i.

Diagram of a Pressurized Liquid Only Sewer system (PreLOS). | Illustration: courtesy of Orenco Water

“The solutions have to be wastewater treatment systems that do denitrification. It’s a straight line between the science and the solution,” Asner says. “People are going to have to figure out how to decentralize wastewater treatment and get it moving in subdivisions that are growing fast. In South Kona alone, there is an explosion of development.”

Heather Kimball, chair of the Hawai‘i County Council, is working with Asner to find practical solutions to protect valuable reefs. She says, “There are three things we can do: Provide incentives to connect (homes) to existing wastewater treatment systems; encourage transition to on-site treatment systems that remove nutrients as part of their function; and look at installing smaller multi-household distributed systems.”

Kimball hopes to get support from OSCER, Hawai‘i County’s new Office of Sustainability, Climate, Equity and Resilience. “OSCER’s kuleana will include both natural resource protection, as well as looking for opportunities to save energy and expand reuse with treated wastewater,” she says. The treated water can be reused for irrigation, landscaping and other uses.

The High Cost of Conversion

The biggest challenge is how to fund the conversion of 83,000 cesspools across the state. In Hawai‘i, conversion costs range between $30,000 and $50,000 per home. The estimated total cost would be about $3 billion to $4 billion, and it’s not clear who would pay those bills.

At the state level, the Hawai‘i Department of Health has been working on a pilot program with the EPA to give counties access to forgivable federal loans through the State Revolving Fund program to help with the costs of converting their cesspools. “The counties will pass these funds in the form of grants to homeowners for cesspool upgrades,” says Sina Pruder, the Wastewater Branch chief. “DOH is committed to providing up to $1 million to each county in fiscal year 2024 for their respective pass-through programs.”

Currently, DOH can only offer the forgivable loans from the State Revolving Funds directly to the counties, but for the last two years, the counties haven’t been able to figure out how to process these funds for homeowners. One solution would be to amend the state’s Intended Use Plan so eligible nonprofits can access the revolving funds to help homeowners with the conversion process.

The revolving funds pilot program is a good start, but the EPA and DOH will need to increase that initial funding of $1 million for each county dramatically to cover the cost of replacing cesspools across Hawai‘i. In 2022, the state passed Act 153 to offer rebates of up to $20,000 to help homeowners with the costs of conversion. Demand was so great that applicants depleted the $5 million fund in less than a week.

When the Cesspool Conversion Working Group delivered its final report in 2022, it included a list of recommendations to the state Legislature. Two of the top recommendations included creating a new cesspool section at DOH and establishing earlier deadlines for priority areas where cesspools pose significant health and environmental risks. A cesspool section would streamline the permitting process, and earlier deadlines would increase the rate of conversions. The current rate is fewer than 300 per year, but that will need to increase to 3,000 per year to meet the state mandate to convert all cesspools by 2050. But after not passing any bills this year related to the working group’s recommendations, some legislators seem to want to continue kicking the can down the road. Meanwhile, new research shows time is running out.

Who is responsible for cleaning up this mess: the state or the counties? The counties are in charge of municipal sewer systems, but the state oversees permitting of all individual wastewater systems, including cesspools. Traditional gravity sewer lines are expensive (over $1 million per mile) and building them blocks roads for months at a time, so they are unfeasible for remote, rural communities. But the counties could work with the state to create local, decentralized systems like the one planned for Mā‘alaea to treat and reuse wastewater.

In the end, we will all have to work together to solve Hawai‘i’s massive sanitation problems. That includes the state and the counties, federal agencies and local nonprofits, scientists and concerned citizens.

The upsides include economic opportunities for workforce development, like the new Work-4-Water program to train workers on Maui and Hawai‘i Island in the rapidly growing wastewater industry. Gov. Josh Green says that converting cesspools “is an incredible opportunity for us to protect our water and environment and simultaneously create a new industry and hundreds of high-paying jobs.”

The federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the federal Inflation Reduction Act provide large amounts of grants for infrastructure improvements, especially in poor, rural and disadvantaged areas.

“I view federal grant opportunities like this as a way to jump-start a new area of economic development in the green jobs space,” Green says. “We shouldn’t pass it up.”

Hawai‘i’s government agencies must apply for these grants or lose a once-in-a-generation opportunity to access vast federal infrastructure funding to clean up the Islands’ waste.

Assembling People to Protect The Reefs

Along with building a new coral propagation and reef restoration facility in Kailua-Kona, Greg Asner says the ‘Āko‘ako‘a program will collaborate with government agencies and offer “multimodal education.” The program seeks to educate decision-makers and the public about the importance of protecting our coral reefs.

Members of the Cesspool Conversion Working Group have offered to continue their volunteer work and to help implement their list of recommendations, but so far the state and counties have not acted on those recommendations. Often, state and county agencies work in silos and don’t include local nonprofits and community groups in their efforts. But Kathy Ho, deputy director for Environmental Health at the state DOH, suggests that “the state can leverage existing partnerships with trusted community organizations and other stakeholders to conduct outreach focusing on the protection of our coral reefs by reducing wastewater and nutrient pollution from cesspools.”

DLNR’s Division of Aquatic Resources is working with Asner on community outreach for the new ‘Āko‘ako‘a program. The division is also trying to increase herbivore fish populations through its Holomua Marine Initiative. “Holomua aims to help align and coordinate place-based work being done to reduce land-based sources of pollution with marine management actions so that these efforts can work to complement each other,” says the Division of Aquatic Resources’ Luna Kekoa.

A new organization called Fish Pono – Save Our Reefs is on a similar mission to educate decision-makers and fishers about the dire need to limit the overfishing of reef fish. As one of the founders of FishPono.org, Mark Hixon, a marine biologist at UH Mānoa, says overfishing is a hard challenge to overcome. Few of those in power, including politicians and the fishing industry, he says, understand or want to acknowledge the critical link between healthy herbivore populations and healthy coral reefs.

Because coral reefs are the living foundation and building blocks of life in the Islands, we would do well to protect them. Referring to the new paper in Nature, Asner says: “As complex as it is written, the story is really simple and straightforward. It’s also very actionable. The paper is not saying, ‘Oh, well, there’s no hope.’ It’s saying, ‘Wait a minute, we have a major role to play on land in how these coral reefs are doing.’ ”

Improving Hawai‘i’s sanitation practices will play a key role in the health and survival of our reefs. “It’s a hallmark of a good society to have access to effective sanitation,” says The Nature Center’s Kim Falinski, who also worked on the Nature paper. “Technologies are available to reduce those impacts, and it’s worth it to protect our reef and coasts.”

Now, Hawai‘i’s policymakers need to weigh the costs of improving the Islands’ sanitation systems with the value of its coral reefs and coastal areas. Once they agree it’s worth it, the transformational process of converting cesspools, reducing sewage pollution and protecting the health of Hawai‘i’s coral reefs can begin.

Stuart Coleman is a public speaker, freelance writer and the author of three books, including “Eddie Would Go.” After working as the Hawai‘i manager of the Surfrider Foundation, Coleman became co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit WAI: Wastewater Alternatives & Innovations. He also served as a member of the Cesspool Conversion Working Group.