Neighbor Island Resilience: When Disaster Strikes

A crisis can come in many forms, from the loss of a company’s founder to a volcanic eruption. These Neighbor Island businesses were knocked down and got back up. Here’s what you can learn from their lessons.

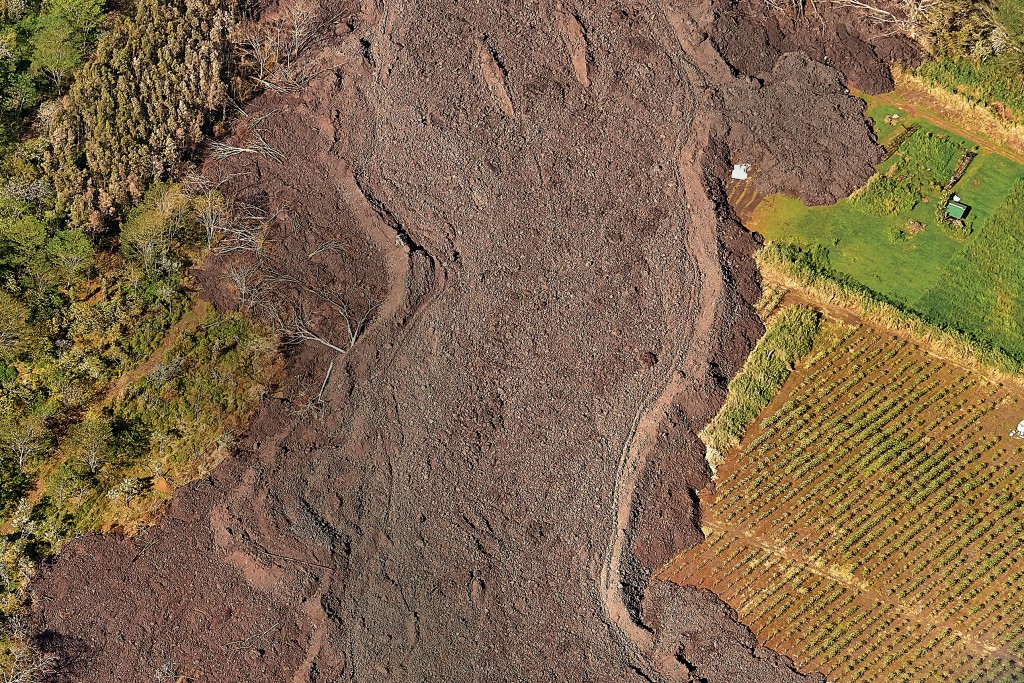

Guides with Arnott’s Lodge & Hiking Adventures were leading a group across the floor of Kilauea Iki crater when a 5.0 magnitude earthquake shook Hawaii Island on May 3, sending boulders tumbling down the crater walls.

No one in the tour was hurt but Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was evacuated and closed to the public soon after. That left business owner Doug Arnott wondering what to do next: His “Crater Hike and Hilo Waterfalls” tour was one of his biggest sellers with cruise ship passengers.

“A few days later, Leilani Estates erupted, which cut off our other major tour,” Arnott recalls. As weeks passed, many sites on his Puna tour were destroyed, including the area’s thermal hot springs, which were buried in lava. “We suffered a complete wipeout of most of the venues we were currently doing with cruise ships,” he says.

The Neighbor Islands are no strangers to calamity. From volcanic eruptions to hurricanes, these islands have learned to face the unexpected – and to bounce back from devastating losses. It may come in the form of a 100-year flood or the sudden loss of an anchor client.

We spoke with five Neighbor Island businesses that were knocked off their feet and recovered. Here’s what they learned about resilience.

■ Arnott’s Lodge & Hiking Adventures; Hawaii Forest & Trail – Hilo and Kona, Hawaii

Like Arnott, Rob Pacheco, founder and president of Hawaii Forest & Trail, knew within days of Kilauea’s recent eruption that the event would batter his business.

“We have five different tours centered around Hawaii Volcanoes National Park,” he says. “It was obvious to us that whatever we could do would not replace the volume, and that the whole event was going to impact just the sheer number of people coming (to Hawaii Island), so it was going to hurt us all around.”

Pacheco quickly convened his department managers, asking them for ways to cut back. “You’re always trying to run your business as efficiently as possible, but when you have some thing like this, it’s funny how things can pop up that you didn’t see before.”

They tightened cellphone use, found a cheaper option for leasing office printers and copiers, and changed their IT management, HR and payroll servicing. They even looked at the sodas they served guests on their tours. “We ended up going to the little cans,” Pacheco says. “A lot of times people don’t even drink the whole can, they were just throwing it away.”

Rob Pacheco of Hawaii Forest & Trail. | Photo: Dino Morrow

And they found substitutes for the lost tours. The company had a longstanding relationship with a ranch that bordered the national park. They quickly worked out an agreement to take tours into a part of the ranch that had a view of the Kilauea rift zone, including the occasional ash cloud during eruptions. “We actually had this vantage point that no other tour company had,” Pacheco says.

Arnott also reorganized his tours, including a popular one focused on visiting lava flows. Arnott realized there were still plenty of historic lava flows accessible from Saddle Road. “We turned it around, rewrote the script,” he says. The company presented its revised tour to Norwegian Cruise Lines, which accepted it.

It helped that Arnott also operates a small hotel in Hilo. When the park closed, so did Kilauea Military Camp, leaving many groups looking for affordable accommodations. “We got a lot of business from that, which really helped us through the crunch,” he says.

Arnott says a conservative, longterm approach to business – including paying off his fleet of tour vans when times were good – helped him weather the storm. “If you have 17 vehicles, and each one is costing you $600 to $1,000 a month, and suddenly business stops, you’re in deep kim chee right from the first blow,” he says, “whereas if you’ve been conservative over time and bought the vehicles as you can afford them, you can be a bit more resilient.”

Pacheco sees a silver lining. Volcano viewing areas and the national park had grown crowded, and there was so much demand for nighttime lava viewing tours that it was straining his staff. Once the dust settles, Pacheco is ready to get back to more normal operations. “We probably are not going to get up to the numbers we were at with that nighttime draw,” he says, “but it’ll be healthy.”

■ Chris Hart & Partners – Wailuku, Maui

In retrospect, Jordan Hard recognized signs that his father, Maui planner Chris Hart, knew his upcoming heart surgery would be risky. In the preceding weeks, he gathered with family and friends, and kept mentioning that Jordan would be taking over the company, Chris Hart & Partners.

“He did a number of putting-his-house-in-order kind of steps,” Jordan Hart re calls. “At the same time, he was acting like the surgery was low-risk and he completely expected success. When I dropped him off at the airport, it was just like you would drop your dad off for an interisland flight, ‘OK, see you later,’ which is one of those things you don’t think about until after.”

The surgery, to repair a bifurcated aorta, ended up releasing plaque from Hart’s arteries, causing a series of strokes. Hart never came out of anesthesia, and he was re moved from life support and died on Nov. 12, 2012.

But even as Jordan Hart was reeling from the personal loss, he knew he had to help Chris Hart & Partners survive. Jordan had bought the business from his father a year and a half earlier, but the elder Hart was still deeply involved in projects, client relation ships and mentoring his son.

Chris Hart founded the company in 1991 after many years as a planner with the County of Maui, where he eventually served as planning director. Originally a land scape architecture business, developers on Maui increasingly asked Hart for help with land use entitlements and planning. “That ended up be ing the emphasis of the company, and it grew from there,” Jordan Hart says.

When Jordan Hart bought the company in 2011, the plan was for Chris Hart to stay on as an advisor, an arrangement that would be phased out over five years. The elder Hart’s death less than two years later had an immediate impact. The firm lost a couple of clients, which Jordan Hart says he understands. “Going from some one who was 71, with over 40 years of experience in the industry, to someone who was 36 without a big public presence – if you’re a developer with a $100 million project, you’re looking for certainty,” he says.

At the same time, Chris Hart’s seniority meant he had the highest billing rate in the firm. “My billing rate wasn’t escalated to his rate,” Jordan Hart says. “So all of a sudden we had a big hole in our income.”

And though his father had been grooming him to take over since he joined the company in 2005, Jordan Hart immediately felt overwhelmed.

If you’re planning to have someone succeed you, you really have to groom them.”

– Jordan Hart, Owner, Chris Hart & Partners

“From my perspective, I wasn’t ready,” he says. “You don’t even know the decisions you’re making until you’re put in a position to make them. I was in complete panic.”

Like Pacheco, Hart’s first move was to cut costs. He renegotiated the company’s lease, cut recurring expenses that he didn’t think were necessary, and took a hard look at things like advertising and sponsorships. “We used to sponsor ‘The Writer’s Almanac’ on NPR,” he says. “Even though there’s value to it, I couldn’t sustain things like that.”

Hart prioritized clients who stayed with the firm. “The most important thing was just doing our job – get ting the permits, finishing the projects we were doing. There’s a lot of repeat business in our industry, so just performing for our clients was really what mattered most.”

To bring in new business, Hart cast a wider net. “I started pursuing projects we didn’t normally do, like state-level contracts,” he says. “Even ones that were maybe out of our league, we’d put in proposals, and several of them we ended up getting. I was surprised,” he says with a laugh. Hart also got accustomed to keeping his radar up at all times to find business in unexpected places, like referrals from people he thought were outside the development circuit. “When you’re looking for opportunities, they can be anywhere,” he says.

While Jordan Hart took many steps to help the business survive, he also credits his father for years of work preparing him. “If you’re planning to have someone succeed you, you really have to groom them,” he says.

In addition to serving as project manager for all the projects Jordan Hart worked on, Chris Hart would often call him early on Sunday mornings to discuss news re lated to planning and development and would bring him along to important meetings with clients and government leaders. “I wouldn’t say any thing, but I was observing,” he says. “It really helped me to hit the ground running when I was in charge.”

One thing Jordan Hart didn’t touch was the company name, Chris Hart & Partners. At first, he felt keeping his father’s name on the business provided an important sense of continuity. Now, he says, it just feels right. “May be someday I’ll change it, but I don’t think it’s the right time yet,” he says. “From my perspective, he’s a pretty good person to have the company named after.”

■ Hasegawa General Store – Hana, Maui

When Hasegawa General Store burned to the ground in August 1990, it could have been the end of the Hana landmark that had been founded 84 years earlier. Not only had the business lost everything, the fact that the fire appeared to be arson left GM Neil Hasegawa embittered and wondering whether he should even try to rebuild. “I had a really negative feeling, like I can’t believe someone would do this to us,” he re calls. “I went through a point where I was like, ‘This sucks. You try to be the good guy, and this happens to you.’ After a couple months, my dad was like, ‘Well, what do you want to do? This is your ball.’ We made a decision together.”

Hasegawa’s General Store’s Neil Hasegawa says his employees were key to successfully rebuilding the store after a fire burnt it down in 1990. | Photo: Ryan Siphers

Helping to nudge him back on his feet was an offer from the Hotel Hana Maui (now called Travaasa Hana) to lease an old theater that the hotel was using for storage. “They said, if you guys can renovate the building, get it up to code, you can have it as a retail space,” he recalls. That support, and support from the Hana community, rallied Hasegawa’s spirits and motivated him to reopen the store. But it wasn’t easy. “It really tested our resolve,” he says. “We had no building, we had basically nothing, we just had our staff.”

Hasegawa decided to keep his entire staff on payroll, putting them to work renovating the theater. “All the staff would help with the carpentry and building,” he says. “Whatever people could do, we would do.” At the same time, the family worked to reopen their gas station, which had burned in a separate fire. “We had to get new pumps, but the gas tanks were still good, so we were able to open that faster,” he says.

The gas station was up and running again after about six months. “After that, we had some kind of income coming in, and it provided another place to get gas for the community,” he says. Hasegawa’s customers started coming back, even while the renovations were underway. “People would come by and say, ‘I just need this one part.’ And they would have to go all the way into Kahului for it – four hours to get a $2 part,” he says. “So we started carrying bits and pieces so people wouldn’t have to do that.” Seeing the need for a general store in the community, and stepping up to fill the gap, further motivated Hasegawa to get back on his feet.

The store reopened in the renovated theater about a year after the fire.

Looking back, Hasegawa sees that many pieces had to fall into place for Hasegawa General Store to rebuild.

“I think there are a lot of things that if we were in a big city, we would not have continued. But being in Hana is definitely something special, and we’re thankful.”

– Neil Hasegawa, GM, Hasegawa General Store

“The most important deci sion we made was keeping everyone employed,” he says. “I think if we had hired contractors, all our employees would have had to find new lines of work. We didn’t break momentum where we said, ‘Now that we’re up and running we gotta find cashiers, we gotta find office managers.’ No, we could get back in gear again and start retailing.”

Though the fire initially left him with a bad feeling,ultimately the experience re affirmed his faith in the Hana community. “I think there are a lot of things that if we were in a big city, we would not have continued,” he says. “But being in Hana is definitely something special, and we’re thankful.”

■ Tip Top Motel Cafe & Bakery – Lihue, Kauai

When you’ve been serving customers for more than 100 years, you have a different perspective on the ups and downs of business. “The Second World War was a boom time for our business, but after that things kind of slowed down. Business comes and goes,” says Owen Ota, VP and office manager of the Tip Top Motel Cafe & Bakery in Lihue, Kauai.

But the business, which has spanned four generations of the Ota family, faced its biggest challenge in 1992, when Hurricane Iniki hit. The storm battered the hotel and restaurant, causing an estimated half-million dollars in losses. “We took quite a bit of damage,” Ota says.

Owen Ota of Tip Top Motel Cafe & Bakery says businesses have to commit to recovering from disaster. | Photo: Mallory Roe

After determining that a large oven destroyed by the storm would be too expensive to replace, the Ota family decided not to reopen the bakery. But they never considered walking away from the business for good. “I don’t think we looked at it that way; we just looked at it that we had to make a recovery, we just had to do it,” Ota says. “You can’t think you’re going to close up.”

Securing financing was the biggest challenge, but once they got the funds, they started rebuilding the hotel and restaurant. Within three to four months, Tip Top re hired its employees and was back in business.

Ota says the key to recovering from a disaster like Iniki isn’t any one particular action: It’s a mindset. “You have to make that decision – whether you’re going out of business or continue. And once you make that commitment, you have to try your best to get it done.”