The U.H. Brain Lab Watched Me Think

he lab’s studies into the human mind open many possibilities, including helping paralyzed people to speak and improving traffic safety

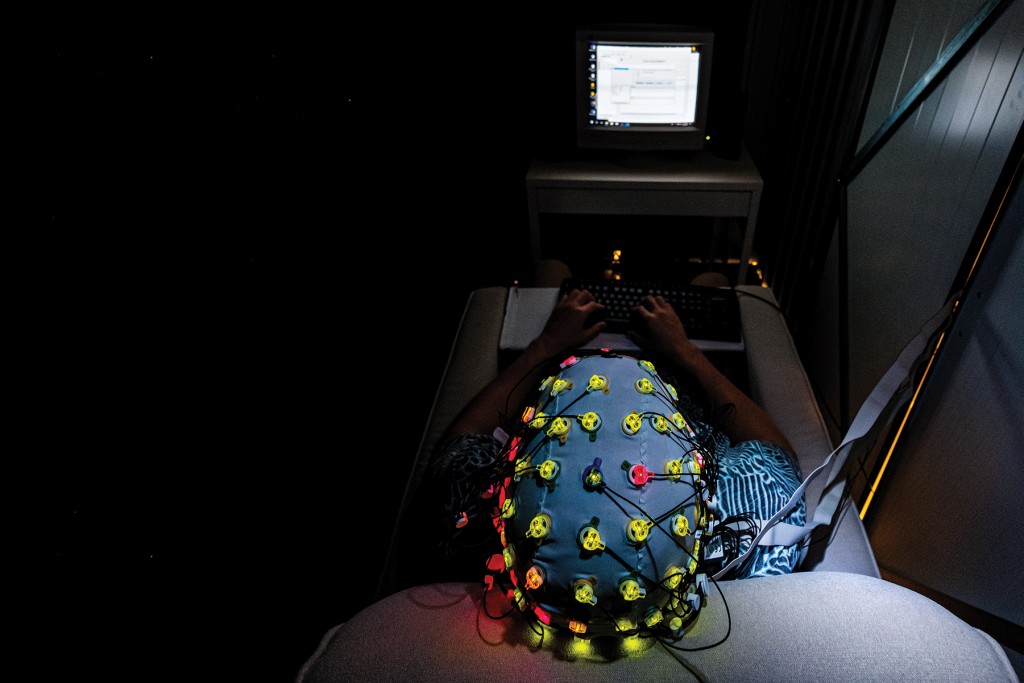

There were 68 wires protruding from the cap on my head, which allowed a whole team of researchers to look inside my brain.

They had me sitting inside the dark testing booth at UH Mānoa’s Brain and Behavior Lab. A computer monitor told me to press the up arrow every time a specific letter of the alphabet was displayed in a rapid-fire random sequence, and the down arrow for the rest. Meanwhile, the researchers watched the electrical activity in my brain.

I got used to quickly pressing the down arrow over and over, so it was surprisingly hard when I had to change to up. I was pressing the wrong key often and self-conscious about all these brain scientists seeing me screw up. The simple sounding task was proving tricky and I struggled to focus. What if I was an air traffic controller with hundreds of lives depending on my powers of concentration?

Left to right, Jonas Vibell, David Thinnes and Tien Austin fit the EEG cap onto reporter Hawe’s head.

My mind was inclined to find a pattern in the sequence. Anticipating I would see the target letter next, I struck the wrong key again. But there was no pattern. By the fifth test, I was losing track of which letter to watch for

this time.

I consider myself a reasonably intelligent human capable of complex tasks. But this seemingly mundane task was confounding. My brain recognized the target letter yet my finger did not always react appropriately. It felt like there was a disconnect between the two.

Brain Science Reversing Brain Drain

The UH Brain and Behavior Lab is a brain imaging laboratory that seeks to understand brain and behavior function and apply that knowledge in everyday life to improve the world, says founder Jonas Vibell, an assistant professor in behavioral and cognitive neuroscience with the Psychology Department at UH Mānoa.

“Cognitive neuroscience is applied in a wide variety of fields, many that might surprise you and me – often,” Vibell says. Direct applications include clinical treatments and therapies for disorders and developing technologies to improve brain function and human behavior. Through its research, the UH brain lab is creating STEM training opportunities and building more capacity for innovation within the community, Vibell says. He also sees the lab developing technologies that will attract tech talent.

Researchers inject a saline gel under each electrode to create a better electrical connection through writer Jeff Hawe’s hair.

“Seeing young people move away because the field they want to get into does not exist here is something that’s pained me,” he says. The lab has received much interest, including from people who left Hawai‘i to study and work in cognitive neuroscience and want to return. Vibell believes the lab can attract the talent to conduct research that ultimately will spin off into creating local economic opportunities in tech.

Scott Sinnett is a psychology professor and undergraduate chair of the College of Social Sciences at UH Mānoa. He works with Vibell and says the lab is not only drawing new students to UH but involving current undergraduate and graduate students “in cutting-edge research and innovation.”

Sinnett believes the lab can help in other ways. “Learning these types of technical skills can advance the skill set of the workforce in Hawai‘i. … From the undergraduate level to industry level, it just makes the (workforce) stronger all around knowing how advanced research is conducted,” he says.

What is Cognitive Neuroscience?

The Cognitive Neuroscience Society explains the field as an interdisciplinary approach to understanding the nature of thought by studying neural systems in the brain. Essentially, Sinnett says, it’s looking at how humans pay attention to things and perceive things.

To measure electrical signals and blood flow in the brain, the lab uses different technologies including functional magnetic resonance imaging conducted in collaboration with The Queen’s Medical Center and a cap called an electroencephalogram (EEG).

Vibell picks up the heavily wired white stretchy-mesh cap that I wore. “On this cap here, you can see 68 electrodes which cover one specific area of the brain. So, you put on this swim cap with these electrodes and then we make people do some sort of task,” he says. The tasks vary but are designed to stimulate the brain in distinct ways while allowing a researcher to isolate the resulting brain activity.

I asked Vibell about my “performance” on the test. He assured me it was normal and that the tests are designed to be tricky to require concentration. We don’t want it to be a mundane task, we want the brain to remain engaged, he says. My confidence in my reasonable intelligence began to return.

The lab is beginning to work with a new technology called Optically Pumped Magnetometry. OPM is a new type of magnetoencephalography (MEG) device that measures the magnetic fields of the brain’s naturally occurring electronic impulses. “MEG has fantastic temporal resolution so you can get many pictures in a row of when brain activation changes, but it also has good spatial resolution so you can see with improved clarity where things happen,” Vibell explains.

UH is the first university laboratory in the U.S. to have access to that technology for brain research, Vibell says, adding that OPM is full of potential and will give UH an edge on other universities doing this type of research.

Global Collaboration for Local Innovation

It’s sort of like reading minds, which we are actually not very far away from,” Vibell only half-jokingly says about a collaboration with Oiwi Parker Jones, a research fellow in the departments of Clinical Neuroscience and Engineering Science at the University of Oxford in England.

Parker Jones elaborates: “Jonas and I are collaborating on a project to try to interpret ‘imagined speech’ in healthy controls using a kind of noninvasive brain recording called EEG.” They are using the UH lab’s EEG equipment and Vibell’s expertise with it to gather data on brain activity while reading and hearing language. The ultimate goal is to develop speech prosthetics for paralyzed patients, technology that can read a patient’s attempts to communicate and turn that into language, Parker Jones says.

Jonas Vibell is an assistant professor in behavioral and cognitive neuroscience with the Psychology Department at UH Mānoa and founder of the Brain and Behavior Lab. He is pictured in front of the lab’s testing booth.

Parker Jones is from Hilo and a graduate of the Nāwahīokalani‘ōpu‘u Hawaiian language immersion school. “I grew up as part of a language revitalization movement, and, in many ways, the theme of language recovery has continued to motivate my entire research career,” he says.

Vibell says research collaboration in science is one of the best ways to come up with new ideas. Aside from the project with Parker Jones at Oxford, the UH brain lab is working with two professors representing a broad group of German laboratories. Learning about their research and how it’s applied in Germany has sparked ideas for translating and adapting similar research to Hawai‘i, Vibell says.

“They have been pushing the frontiers on neuroscience things related to car manufacturing. One of the things they talked about was traffic safety. That’s something we have a problem with in Hawai‘i and it’s something that they have come pretty far on. We have to explore to see if there is something viable that could work here,” he explains.

“The brain is like an imploded universe. It’s 86 billion neurons with a thousand trillion connections. Just trying to comprehend that is difficult. Even though we’ve come a long way, we still have a long way to go. … We now have better technologies than we’ve ever had in the history of humankind to actually look at brain activity in alive people noninvasively while they think about things. It’s an exciting time for us.”

Learn More

The UH Brain and Behavior Lab officially opened in 2016. It currently facilitates research for up to 30 students and five to 10 collaborating faculty from UH and around the world.

Founder Jonas Vibell says he is happy to talk to groups, classes and individuals interested in the Brain Lab. Go to brainandbehaviorlab.com.