Crowded Water

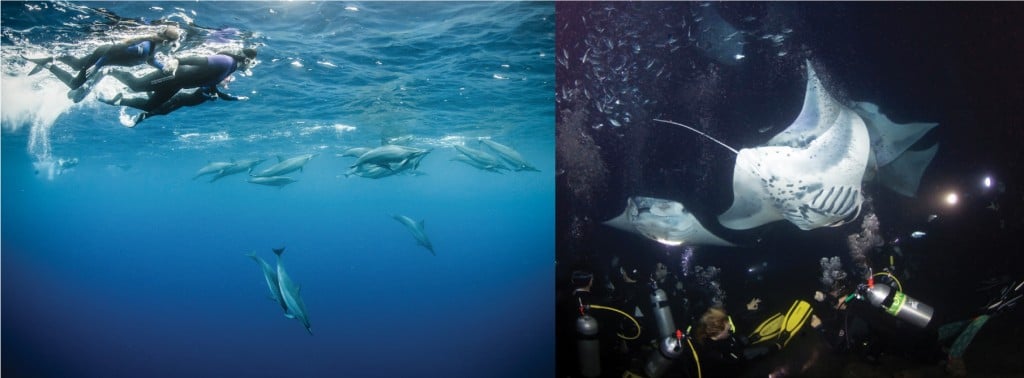

THE TRAVEL CHANNEL named Kona’s manta ray night dive one of the top 10 things to do in your lifetime. As they feed on the plankton attracted to the flashlights held by divers and snorkelers, the gentle yet massive rays, with wingspans of up to 16 feet, somersault and swoop close to their audience in an otherworldly underwater ballet.

THE TRAVEL CHANNEL named Kona’s manta ray night dive one of the top 10 things to do in your lifetime. As they feed on the plankton attracted to the flashlights held by divers and snorkelers, the gentle yet massive rays, with wingspans of up to 16 feet, somersault and swoop close to their audience in an otherworldly underwater ballet.

Keller Laros, the “Manta Man” at Jack’s Diving Locker, remembers just a few boats going out every week when the dives started in the mid-1980s. Now that the dive is internationally known, much has changed. “During busy season, we see at least 20 boats at the site, putting over 200 scuba divers and snorkelers in the water every evening,” Laros says.

Other businesses focused on marine-life encounters have also grown significantly. Any Hawaii guidebook or travel magazine reveals that spinner dolphins and humpback whales are also among the state’s most popular attractions. That’s good news for the economy and the business owners, but raises concerns about balancing customer demand with the safety of these creatures. Both businesspeople and scientists have noticed, with alarm, increased animal harassment. “If the free market is unrestrained, it’s going to be destructive at some point,” says Laros.

Photo: Doug Perrine

Growing Pains

Growing Pains

State and federal regulations and voluntary guidelines have helped safeguard Hawaii’s ocean life, but they haven’t prevented all problems.

One issue, according to some operators with decades of experience, is the low barrier to entry. To start a snorkel boat tour company, such as those that take people to swim with manta rays and dolphins, a company needs only three things:

- A commercial-use permit from the state Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation;

- A boat operator with a captain’s license; and • A vessel registered commercially with the state or documented with the U.S. Coast Guard.

While the operator may require its snorkel guides to have lifeguard training, that’s not required by the state. No training in marine-life behavior or safety is required. “All these people with no experience are now running trips,” says Deron Verbeck, a captain with Wild Hawaii Ocean Adventures and an underwater photographer who is constantly in the ocean. “I’ve seen really poor skill levels with these captains. I’ve had guys almost run over my guests; they just don’t pay attention. The manta ray site went from a couple a week to some guys doing three dives a night. I know of tours that are doing multiple dolphin swims a day. The dolphins aren’t getting any rest. They are constantly bombarded.”

Some operators concerned about the safety of animals and customers want mandatory safety training. “You’ve got more tour companies trying to make money and selling snorkel tours to people who can barely swim,” says Keller Laros. “The last thing anybody wants is for someone to get hurt. We need to require all snorkel guides to have in-water safety training as a rescue diver or lifeguard.”

Victor Lozano, president of Dolphin Excursions Hawaii and a licensed captain for over 32 years, was an early advocate of restricting the number of operators. In 2000, he helped introduce state legislation to limit the number of dolphin-viewing companies on the Waianae Coast. He says the legislation died because of lack of support from charter companies that wanted to keep growing. Now, he fears it may be too late. “It’s gotten really out of hand, it’s very visible. I have friends in the local community who have been chased out by commercial boats,” he says.

While newer operators insist it is their right to be in the business if they meet the legal requirements, established operators complain that “gentlemen’s agreements” developed when there were fewer companies are breaking down. These agreements typically involve self-imposed time restrictions, understandings about how to share moorings and procedures to keep swimmers and animals safe.

“You may have well-meaning operators who understand the issues and agree to do something, but then you get new people come in who may not buy into the system,” says Bill Walsh, aquatic biologist at the state Division of Aquatic Resources. “If it’s a lucrative attraction with low entry costs, the likelihood of people not paying attention to what’s agreed becomes greater and greater.”

PHOTOS: DOLPHINS: SHAWN HENDRICKS, MANTA RAYS: BO PARDAU

Despite the plethora of guidelines, what matters most is whether people actually follow them. Tori Cullins, a marine biologist, founder of the Wild Dolphin Foundation and owner of Wild Side Hawaii, is a strong advocate for voluntary standards. However, she says, “The biggest issue is that there’s no enforcement of anything, such as the guidelines from NOAA, the West Hawaii Voluntary Standards or Dolphin Smart. In fact, it’s harder to get something enforced or to report something than it is to get certified to be Dolphin Smart.”

“THERE’S PLENTY OF MONEY BEING GENERATED BY MARINE RECREATION, BUT IMPORTANT ACTIVITIES LIKE MANTA RAY DIVE MANAGEMENT ARE LEFT UNFUNDED, EVEN THOUGH THEY ARE GENERATING MORE THAN ENOUGH MONEY TO TAKE CARE OF THEMSELVES.”

—Brian Szuster, Associate professor, Geography Department at UH-Manoa

Though regulations carry penalties, many people are concerned by a lack of enforcement manpower in some areas. Fair Wind Cruises, started in 1971 and the oldest original family-owned snorkel business in the state, and several other operators on Hawaii Island have offered to take enforcement personnel out when they need a lift. “We need the state and the Coast Guard to come out and really see what is going on so they can wrap their heads around making some strategy to help control the numbers. They are shorthanded and many times they don’t even have a vessel to use,” says Fair Wind VP Mendy Dant.

Manta Ray Dives

Manta Ray Dives

On top of the general concerns about the number of operators, their inexperience and the lack of enforcement, are issues specific to tours that target manta rays, dolphins and whales.

The manta ray night dives off the Kona coast of Hawaii Island started in the early 1990s with tours geared primarily toward scuba divers, who must take required training courses and be certified. Newer businesses focus on snorkelers, who don’t need to be certified. That means more people with poorer water skills.

Some operators also use questionable practices that endanger the manta rays, Laros says. “Lights attract plankton, which the mantas feed upon. We’re seeing new operators putting lights at the back of their boats to get the mantas to come closer, so people can just stand at the back of the boat and not get in the water,” Laros says. “If the mantas are doing somersaults, they can run right into the ladder and into the propeller. And inexperienced guides are positioning their floats with all their lights and people without considering where they are going. Mantas run into their lines. We’re seeing mantas with nasty cuts.”

The coral reef has also suffered. Given the limited number of moorings at each manta ray site, inexperienced captains are dropping their anchors onto the coral rather than tying off to other boats or guiding their anchors down with a diver, says Walsh.

Laros and others in the operator community want mandatory training. “What we need to have is a manta ray tour operator permit. Until you meet certain criteria for that, you should not be allowed to run a manta business. Captains would need to adhere to certain standards, and the crew would be required to have certain training.”

Brian Szuster, an associate professor in the Department of Geography at UH-Manoa, conducted research on the manta ray dives and concluded the recreational experience has been degraded.

“At present, it’s pretty much an open-access resource,” Szuster says. “There are plenty of great operators, like Jack’s Diving Locker, who invested a lot of time and money into building this experience into something unique, well known and economically important. But, if it’s open access, anyone can apply for a commercial-use permit, buy a used Zodiac and take people onto the site. The tendency is for more and more operators to come in, make some money quickly and not be too concerned about the long-term viability of the site.”

One potential solution, he says, is spending more of the fees collected from boat operators to police the industry. Commercial operators pay a monthly fee to the state Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation of either $200 or 3 percent of their gross receipts. If they have a harbor mooring, they also pay two times the standard mooring rate or 3 percent of their gross receipts. The fees collected from the commercial use permits go into the state’s Boating Facilities Special Fund.

However, there is no mechanism that directs any of the fees specifically for managing manta ray dive sites. “There’s plenty of money being generated by marine recreation, but important activities like manta ray dive management are left unfunded, even though they are generating more than enough money to take care of themselves,” Szuster says.

Dolphin Swims

The opportunity to swim with wild spinner dolphins is, for many visitors, the adventure of a lifetime. More so than most other marine animals, dolphins inspire wonder and curiosity. “A few moments of being with the dolphins, and there’s a connection that happens, that people write books about. It’s instantaneous. It’s inspiring,” says Joe Noonan, owner of Dolphin Whisperers, who has brought people to swim with dolphins since 1995.

Noonan leads small groups of swimmers from shore, so the dolphins control the interactions – when to approach and leave. He emphasizes respect for the animals and properly reading their body language. “We never dive when they are sleeping, we just stay on the surface. When they are in a playful mood, we don’t dive in front of them. Plenty of times they come straight over, but we never go straight toward them. I try to match and honor the behavior of the dolphins in the moment,” he says.

Other operators, however, engage in more aggressive practices. Various boat captains and scientists interviewed for this article confirmed they have witnessed some operators use questionable tactics such as “leap frogging.” Boats race ahead of a pod of dolphins on the move and put snorkelers in the water right in front of them. Once the dolphins pass, the boats pick up the snorkelers and do the same thing over and over. Another tactic involves boat captains working together to corral dolphins into swimming toward snorkelers.

“These are some of the most harmful behaviors you can do to dolphins. The animals are not stopping to hang out, they are clearly on the move,” says Carlie Wiener, who is a Ph.D. student in environmental studies at York University in Toronto and whose research involves Hawaii’s dolphin-swim tourism.

Marc Lammers, associate researcher at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, explains the less obvious ways activities can disturb dolphins. During the day, dolphins seek out shallow waters close to shore, which offer protection from predators such as tiger sharks, so they can rest. They switch off their main sensory channel, which is sonar, using visual input and tight group formations to detect predators. When curious individuals – typically juveniles – break away from the group to interact with snorkelers, it disrupts the group cohesion necessary for resting.

“They end up distracting mothers, waking up the group and causing disruption. Even after the boats and people leave, it can take a long time for the group to settle back into its resting mode.” Lammers warns that if the animals feel they cannot rest, they might move to areas that are less safe for them.

While swimming with dolphins may not be illegal, NOAA and other groups strongly discourage that activity as well as getting too close. “Our recommended guideline is 50 yards,” says Laura McCue, coordinator for Dolphin Smart. “At that distance, you can still see the group. And, if we aren’t disturbing them, you might see some natural behaviors including nurturing behaviors between a mom and calf, all of which can be viewed from a boat or even from shore at some locations.”

Several operations, such as Wild Hawaii Ocean Adventures, deliberately do not advertise dolphin swims, even though tourists want them. Verbeck says customers will likely see dolphins during their boat rides, but the company strives to set expectations carefully. “We don’t advertise dolphin swims. If, by chance, they are transiting from one spot to another while we’re in the water, we enjoy it. If there are guests on the boat we may let them join in, but only if the dolphins are cooperative. If I know that the dolphins are sleeping, I choose not to do it,” says Verbeck.

PHOTOS: THINKSTOCKPHOTOS.COM

Whale-Watching

Humpback whales migrate over 3,000 miles from the Gulf of Alaska to Hawaii to breed, calve and nurse their young every year between December and May. They can be spotted from all the islands, but the best place for viewing is the Auau Channel, between Maui, Lanai and Molokai.

Elia Y.K. Herman, state co-manager of the Hawaii Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, describes the whale-watching industry as well managed. This is largely due to the humpback whale’s protection as an endangered species, which makes it illegal to approach within 100 yards. It is also due to the establishment of the sanctuary in 1992, which paved the way for strong partnerships between the sanctuary and the whale watch industry on education, research and response efforts that have benefited both tourism and the whales.

However, as Herman explains, this does not mean humpback whale-watching is without challenges. “Over the last few decades, there has been a tremendous increase in humpbacks coming here, and a growth in the whale-watching industry. The whales are doing well, so much so that NOAA is considering delisting them as an endangered species. This is to be celebrated. That being said, as you have more whales and people, the potential for harmful interactions increases. This includes boat strikes and whale entanglements in marine debris, mooring gear and fishing gear,” she says.

Herman also raises concerns about kayak renters during whale-watching season. While rental operators may know the regulations and best practices, the renters may not know the 100-yard rule. “That’s a place where we could all probably do more and do better for the safety of people and whales.” She adds, “We need to remember that these are wild, 40-ton, 40-foot animals and that whenever we go in the ocean, we are in their house.”

While the whale-watching industry appears to be doing well because there are more whales, Lammers warns that the long-term consequences of our actions may not be obvious. For example, he says, the effect of boating noise on marine life requires more research. While there are no hard conclusions yet, there is the possibility that chronic exposure to noise may increase stress, especially among whale mothers and calves.

Robin Baird is a Ph.D. biologist with Cascadia Research Collective, a nonprofit based in Washington state that specializes in marine mammal research. His personal focus is on the abundance, behavior and ecology of Hawaiian odontocetes, which are toothed whales, a group of mammals that includes dolphins. He points out that while much of the attention on the humpbacks is because they can be easily viewed close to shore, there are also more than a dozen other species that exist further offshore of Hawaii. These include false killer whales, pygmy killer whales, short-finned pilot whales and three species of beaked whales.

Baird notes that, while regulations and guidelines tend to generalize across marine mammals, in reality each of these species exhibits different behaviors and reactions to humans. As an example, he describes false killer whales as similar to spinner dolphins because they can be very curious about boats and people. But, unlike the dolphins, these whales hunt rather than rest during the day, and thus human interactions are less likely to negatively affect them. Short-finned pilot whales, in contrast, rest during the day.

“It would be valuable to develop area-specific and species-specific guidelines to reflect the complexity of the situation. In Hawaii, if a boat goes further offshore, it will encounter whales and dolphins that all behave in different ways,” Baird says.

What’s Next

What’s Next

None of the scientists, regulatory agencies, businesses or marine conservation advocates interviewed for this article want to discourage tourists from experiencing marine animals in the ocean. In fact, everyone agrees that such interest is fundamentally a positive thing. “The increase in offshore tours has made people more aware of the existence of these marine-life populations. If those types of interactions are done in the right way, they can raise awareness and build a constituency of people interested in preserving and protecting Hawaii’s ocean life,” says Baird.

Nonetheless, there is a strong consensus that all of this needs better management. What the tour operator community wrestles with is whether such management requires top-down regulations, or if voluntary guidelines can succeed.

Bill Walsh, the state’s aquatic biologist, believes that, despite people’s best intentions, it is harder to create a voluntary consensus as the number of operators grows. “My perspective is that you can have these codes of conduct or gentlemen’s agreements, but there will always be people who don’t buy into them. At some point, when there’s critical mass, another entity will need to impose some order,” Walsh says.

Others feel that the operators, many of whom got into the business because of their passion for marine life, need to figure it out among themselves. “Shame on us if the government has to step in,” says Noonan of Dolphin Whisperers. “That means we’ve not been good stewards. It’s our responsibility to demonstrate that we are able to manage ourselves.”

Herman, the co-manager of the whale sanctuary, stresses that until a solution is found, consumers should influence how these industries develop. “You have a choice of operators, and a choice of how to conduct yourself,” she says. “Be mindful of that. Do your best to understand their policies before you choose a company.”

EXISTING PROTECTIONS

Because Hawaii’s tourism industry provides easy access to marine animals, it is easy to forget they are often protected under federal and state law.

ILLUSTRATION: THINKSTOCKPHOTOS.COM

MARINE MAMMALS, including Hawaii’s spinner dolphins and humpback whales, fall under the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act. That makes it illegal to feed, hunt, harass, kill, capture, injure or disturb them, or change their behavior.

Humpback whales also fall under the Endangered Species Act, which makes it illegal to approach within 100 yards of them, and they are further protected within the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. Manta rays are also covered. Then-governor Linda Lingle signed a bill in 2009 that made it a crime to kill or capture them in state waters.

In addition to these federal and state regulations, and their penalties, are guidelines that are recommended but not mandatory. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s guidelines recommend that people and boats stay at least 50 yards from most marine mammals, and do not encircle or trap dolphins between boats or between boats and the shore.

Dolphin Smart – a partnership developed by NOAA Fisheries and the National Marine Sanctuaries with two charities, the Whale and Dolphin Conservation and the Dolphin Ecology Project – provides a voluntary education and recognition program for operators.

Other guidelines include the West Hawaii Voluntary Standards for Marine Tourism, developed by Hawaii Island operators and dive-shop owners along with the Coral Reef Alliance and the Hawaii Ecotourism Association. Keller and Wendy Laros, scuba instructors at Jack’s Diving Locker and founders of the Manta Pacific Research Foundation, have worked closely with the tour-operator community to create the Manta Ray Tour Operator Standards, which detail best practices for keeping people and animals safe.

ACT SMART WITH DOLPHINS

PHOTOS: THINKSTOCKPHOTOS.COM

The Dolphin Smart program uses the acronym SMART to highlight what it calls the basic principles of viewing etiquette:

- Stay at least 50 yards away;

- Move away slowly if the dolphins shows signs of disturbance;

- Always put the vessel engine in neutral;

- Refrain from swimming with, touching or feeding wild dolphins; and

- Teach others to follow these practices.