Forever Changed

Iselle battered Pahoa, then lava threatened to overrun it. This sleepy Hawaii Island town persevered, as did most of its businesses, but many other things will never be the same

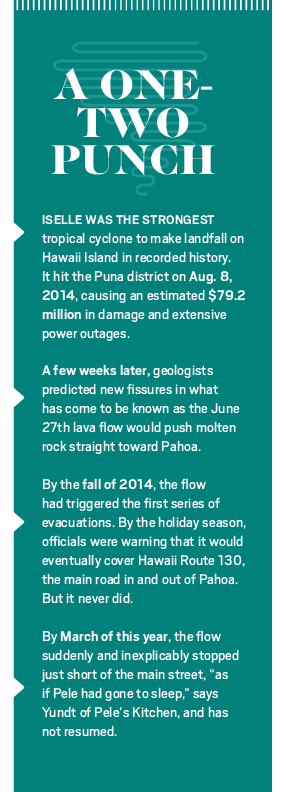

PAHOA, Hawaii Island – Petra Wiesenbauer, owner of Hale Moana Bed and Breakfast for 15 years, lives month to month on her income, without large reserves to get through difficult times. Last year, Tropical Storm Iselle left her Pahoa B&B without electricity and running water for nine days in August, while Kilauea’s threatening lava flow discouraged new bookings for several months.

Petra Wiesenbauer, owner of the Hale Moana Bed and Breakfast, says surviving the one-two punch of Iselle and lava made her more resilient. Photo: Ciara Enriquez

The advancing flow triggered a series of evacuations during the fall and, by the holiday season, civil defense officials warned it would eventually cover Hawaii Route 130, the main road in and out of Pahoa.

But, like other business owners in Pahoa, she did not give up. “I told my children, we’re going to stay here. We’ll leave only if the lava runs us off of our yards. Other than that, we’re going to hold out. I’m a fighter and survivor.”

But, like other business owners in Pahoa, she did not give up. “I told my children, we’re going to stay here. We’ll leave only if the lava runs us off of our yards. Other than that, we’re going to hold out. I’m a fighter and survivor.”

More than a year later, much but not all of Pahoa is back in business, but it’s not business as usual. Here’s how the community suffered, coped, recovered and was forever changed.

Downed Trees and No Power

The biggest issue after Iselle hit was the lack of power. Electricity was restored to most businesses in Pahoa’s central shopping area after a couple of days, but many of those further from the main street had to wait weeks.

No power here means more than just no lights. “One of my challenges is that I’m on catchment,” Wiesenbauer says. “I was without power for nine days. If I don’t have electricity, my water pump doesn’t work. That means people can’t flush toilets and take showers, and that’s a real challenge.”

“Everybody was saying, aren’t you going to evacuate? I said, ‘Only if Pele comes to my door.’ Only if she knocks, then I’ll move my things.”

— Jan Ikeda, Pahoa’s barber for 65 years

Iselle also left many roads blocked. “On my farm alone I lost 15 trees,” says Stephen Yundt, owner of Pele’s Kitchen. “It was decimating. There were hundreds of snapped-over posts and trees everywhere. We couldn’t drive down our street.”

What saved Pahoa initially were the Pahoans, say Alexis Ching and Marina Kelley, who are conducting a Puna Resiliency Study for UH Hilo’s Anthropology Department. Puna district “has one of the lowest income levels on the island. But residents didn’t wait for others to come around. They started clearing the roads themselves using chainsaws. They took things into their own hands,” says Ching.

Others agree that locals were the first responders. This not only solved immediate practical problems, but also drew the community closer. “On my street, we were without power for 14 days,” says musician Jahred Namaste, who runs Love Eternal Studios. “But we shared a truck, a generator and propane. We played a lot of music and games instead of just watching TV in our own houses.”

Matthew and Noelle Purvis, who own the Tin Shack Bakery, felt it was important to open their business the morning after the storm, running as much as they could off a generator. “People were coming by in shock, and we could be a sanctuary for them,” says Matthew. “They could come out of this insane experience, sit down and eat a brownie and drink coffee. It was a way to bring some normalcy back.”

Lava Brings Ongoing Dread

While Iselle quickly created problems, the lava generated months of stress. As the lava crawled closer to town, all business owners had to decide their personal tipping points or just wait for a mandatory evacuation order.

“We were close to closing, but it was our decision to just wait,” says Hardy Ogasawara, whose father started Paul’s Auto Repair and Gas Station over 50 years ago. “We prepared but decided not to leave unless the lava actually threatened our safety. Civil Defense said it would give us three days’ warning to evacuate. But a lot of people were scared, so they left before they had the evacuation notice.”

Ogasawara says some of those who evacuated early ended up losing more than they expected. “They had to spend money packing up, moving and renting another place. I’ve noticed that those who closed up had a hard time regaining their businesses once they came back.”

Others simply believed the lava would not destroy the town. Jan Ikeda, now 79 and the town’s hair cutter for 65 years, vowed not to abandon the barbershop her grandfather had built, unless the volcano goddess personally told her to go. “Everybody was saying, aren’t you going to evacuate? I said, ‘Only if Pele comes to my door.’ Only if she knocks, then I’ll move my things.”

Tropical Storm Iselle left the Hale Moana Bed and Breakfast without electricity or running water for nine days. Now things are back to normal, which includes breakfasts of banana pancakes, Kona coffee and fresh fruit grown in the garden. Photo: Ciara Enriquez

Becky Petersen, owner of Jungle Love, saw the flow come within 450 yards of her store. Faced with the possibility of losing her business, she opened a new store in Kona. Today, she drives back and forth between the two, acknowledging that she has had to delay retirement plans.

“It’s taken me months to recover and this has set me back years financially. Opening another store was not what I would have done had I felt I had any other choice,” she says. “But, now that I’ve done it, I’m going to make it work.”

“I’ve noticed that those who closed up had a hard time regaining their businesses once they came back.”

— Hardy Ogasawara, Co-owner, Paul’s Auto Repair and Gas Station

The lava’s threat to businesses also put a tremendous strain on employees. State Sen. Russell Ruderman employs about 45 people in his Island Naturals store in Pahoa.

“People were asking, ‘Will I be able to collect unemployment if you close down? What if I end up living on the other side of the lava flow and can’t get to work? Can I get a job in the Hilo store?’ The stress level on them was palpable,” Ruderman says. “Unfortunately, some customers added to the anxiety by freaking out in our store and saying, ‘I’m getting out of town, you guys are crazy to stay here.’ ”

There was a silver lining: The idea of seeing live magma in action increased tourism to an otherwise under-the-radar town. Visitors came to see the lava, but stayed to enjoy quirky downtown Pahoa, with its mix of Old Hawaiian and hippie cultures.

“For our business it was a good time, and it lasted four or five months. People didn’t think of coming here before. Everybody goes to Waikoloa and Waimea and Kona, but the lava drove tourism to our town,” says Sal Luquin, owner of Luquin’s Mexican restaurant, which has been in Pahoa for 31 years.

However, as the flow moved closer to town, businesses felt the downside of all that attention. Petersen describes the chaos during the Christmas season: “The civil defense and news crews were all there, making it really disruptive. The National Guard was in the parking lot, which doesn’t make for good feng shui. It was total insanity.”

Leslie Lai, owner of Kaleo’s Bar and Grill, says that, as the lava got closer to Pahoa, distorted or misunderstood information gave outsiders the mistaken impression that the town was completely unreachable or the lava was more dangerous than it was. “We were getting people calling us from Hilo, crying, and saying we’re so sorry, we want to say goodbye and we want to visit you, but we’re scared of the rocks that come out of the volcano. I said, ‘Listen, it’s just a flow, it’s a trickle. You can run faster than it.’ ”

Altered Mindsets

On the surface, things appear back to normal today, but, in fact, they have been forever changed, say Pahoa’s business owners. Many say they are more resilient than ever, which they attribute to four factors.

The first is the power of community. In their study for UH Hilo, Ching and Kelley found that, over the last year, there has been an increase in people coming together to create neighborhood disaster protocols, phone trees and advocacy groups.

Lai, frustrated at misinformation in the media that scared visitors away, invited other business owners to meet at her restaurant and discuss what they could do. “People were not coming because they had heard the road was closed, when, in fact, neither Pahoa Village Road nor the highway had been hit.”

Matthew Purvis, owner of Tin Shack Bakery, thought it was important to open up his business the morning after Iselle hit because that brought a sense of normalcy to the community. Photo: Ciara Enriquez

Wiesenbauer talks about some of the goals the group accomplished. “Early on, the visitor’s bureau put out a lava alert on its website, telling people to stay away from us. Yet they have their main office on the Kona side and, initially, nobody came out to look. We let them know that people could come here and the lava didn’t pose an immediate threat. Working together, we got them to take it off of their website,” she says.

She adds that working together had more than just practical consequences. “Those of us who stayed grew very close. We had this commitment to help each other. And even people who didn’t see eye to eye became allies.”

The second factor is the heightened awareness of how easy it is to be cut off from the rest of the island. If the main highway is closed, two of the three emergency routes are rough cinder dirt roads that also fall along the lava path, and the third one adds up to five hours of travel time from Puna to anywhere north of the flow. Ruderman advocated for new ways in and out, including the development of a harbor at the Pohoiki boat ramp and a small airstrip.

“This is a very magical place. It’s one of the last sections you can visit that’s still Old Hawaii. … But it’s hard for people to make a living, so a few more visitors would be fine.”

— Stephen Yundt, Owner, Pele’s Kitchen

While none of these initiatives passed, Ruderman continues to encourage Puna residents to be ready in case they are ever cut off. “This is a microcosm of the whole state in terms of our dependency on the boats bringing in what we need. I want to see us get serious about food resiliency and food self-sustainability in the event that we do get isolated.”

The third factor is the ability to function off the grid for several weeks. Wiesenbauer, who was without electricity for nine days, feels better prepared now to deal with downed lines and blocked roads.

“I have installed a big generator that is hard wired into the whole house, so it can power everything whether there is HELCO or no HELCO. I have a different stock of supplies here, in case I don’t have access to stores. I’m very conscientious about preparing for whatever might come.”

Leslie Lai, owner of Kaleo’s Bar and Grill, believes there was a lot of distorted information about the lava flow in Pahoa, which scared away visitors and hurt businesses in the area. Photo: Ciara Enriquez

The fourth key factor is the reminder that natural disasters can strike at any time. “The perspective from the outside is that we’re a bunch of insane people doing nothing while Pompeii is exploding,” says Purvis, owner of the Tin Shack Bakery. “The fact is, no matter where you live, you’re at the mercy of nature. Nothing is guaranteed. When you live near a volcano, the awareness of that is simply made closer to home.”

Pahoa’s Future

Mark Hinshaw, president of the Pahoa Main Street Association, says that, although the town is, at least for the moment, enjoying a reprieve from natural disasters, local businesses continue to struggle.

“Before the flow, the town was getting busier and busier. We had a big roundabout project and huge shopping center planned. When the lava flow came, it was like this weird mix of things. More people came and we had booming business. When the lava flow stopped, so did a lot of the traffic in town.”

Local residents have rallied to keep spirits up and draw attention to Pahoa’s businesses. Musician Namaste organizes the Pahoa Music and Art Walk on the second Saturday of every month. Ching and Kelley, inspired by the themes that came up in their research for UH Hilo, organized a Puna Resiliency Block Party in October.

“Unfortunately, some customers added to the anxiety by freaking out in our store and saying, ‘I’m getting out of town, you guys are crazy to stay here.”

— Russell Ruderman, Owner, Island Naturals store in Pahoa

“A lot of the businesses are still suffering. What we want to do is let people see that the businesses are still here, and encourage visitors to come back,” says Ching.

Pahoa remains a sleepy jungle town, but big changes are on the horizon. Hinshaw says Puna is the state’s fastest growing region, with 50,000 to 60,000 properties approved to be built and a new four-lane highway in the works. It’s one of the cheapest places to buy property in the state, attracting what Ruderman calls “economic refugees” from Oahu – middle-class families looking for affordable homes and land.

That growth could change main street Pahoa, which has, so far, retained its small-town, Wild West feel, its neo-Victorian architecture, false-front buildings and wooden sidewalks.

“Pahoa is right in the path of this major growth,” Hinshaw says. “It’s a good thing and not a good thing at the same time. We’re trying to get ahead of the curve and get controls in place in order to maintain the historic look of our town and make sure we don’t just become a bunch of big-box stores.”

Yundt is ambivalent about the town’s growth. “This is a very magical place. It’s one of the last sections you can visit that’s still Old Hawaii. There are hardly any corporations or hotels. It has stayed very rural and diverse. I kind of like it sleepy as it is. But it’s hard for people to make a living, so a few more visitors would be fine. If it’s too many and causes issues, I can see us wanting to go back to being Hawaii’s best kept secret.”

Regardless of what the future brings to Pahoa, Wiesenbauer wants visitors to understand there is more here than meets the eye. “Because we went through all of this, we have developed a different mindset. I am, as a person and a business owner, much more strengthened and resilient as a result of what happened. When people come to visit, I hope they understand this, and can take some of this home with them.”