Living Paycheck to Paycheck in Paradise

Hawaii’s homeless population includes thousands of working people who suffered a financial crisis and lost their place to live. Tens of thousands of others scrape by with jobs that pay little more than minimum wage, but are possibly one or two missing paydays from homelessness themselves. Here are three people in Kona just keeping their heads above water. How do they cope and what are their plans for a better tomorrow?

The Single, Young Adult

For 24-year old Charles Akau IV, making it on a line cook’s wages is all about discipline. It’s the same discipline that got him through the Hawaii Job Corps culinary arts program with no experience in cooking, and helped him lose 100 pounds through mixed martial arts and a diet overhaul.

“Nobody who meets me now believes me, but I used to weigh 300 pounds,” he admits, pointing to a Facebook post showing dramatic before and after photos.

Today, the lean and muscular young adult, who helped his mother sell malasadas while growing up on Kauai, works as a line cook for a popular restaurant in Kona. He makes $1,200 to $1,400 a month after taxes, depending on tourist traffic. After paying $600 for a room in a house in Kealakekua that he shares with two others, $150 for utilities, $120 for food, $100 for his mobile phone plan, $20 to $30 for eating out, and $50 for an old credit card bill, he is left with about $100 to $200 at the end of the month.

He stretches his paycheck using the same regimented approach that helped him lose weight and earn his education. Unlike many of his friends, who spend their pay eating out often, he wakes up early to prepare his three meals plus snacks for the day. These meals, which include his new passion for healthy options such as quinoa and skinless chicken, go with him everywhere in Tupperware containers.

“It saves money by helping me control spending on eating out all of the time. And I know that, at the end of the day, I don’t have to cook, I can just come home and sleep.”

Akau also saves by taking Hawaii County’s Hele-On bus for $2 a ride, rather than buying a car. This requires careful planning because the bus system is limited and unreliable.

“If I want to go to the gym, I have to leave here early to get a good workout in. I have to walk to Alii Drive to catch the bus, and it can take 30 to 40 minutes to get there. That’s where my discipline comes into play,” he says.

Instead of accepting social invitations spontaneously, he makes mental calculations first. “It’s the little invites to go out with friends that will make you go broke. For example, going to the movies: You spend $10 for the ticket, and if you want popcorn and a drink, it’s another $20. Do I want to go to the movies or buy two to three days of food, and watch Netflix instead? I am always thinking about those tradeoffs,” he says.

He has also stopped using credit cards while he pays off debt from his younger, more impulsive years. “I went crazy. I didn’t know what it meant to have a credit card. I was only 18. I thought it was like free money, and spent it foolishly, buying drinks and getting new vitamins. I’m paying for it now.”

Despite his disciplined lifestyle, there’s just too little left at the end of the month to feel comfortable. “It’s a struggle,” he acknowledges. “I’m not always able to make ends meet.”

He’s considering a second job as a line cook, but people warn that’s a tough life.

“A lot of my coworkers have second jobs. It’s very hard for them. Some days they’ll come in late to work, or be really tired, especially during the holidays. You’ll have to call in sick for one job to continue on with another one, just because they need you in that kitchen. It’s very hard to do both. At the end of the night, you’re just burnt out,” he says.

For the longer term, Akau is being mentored by Jamie Borromeo, an entrepreneur and book author who runs Happy Buddha Farm. They talk about new ways for Akau to make money from his skills, and are experimenting with custom, healthy meals for busy people who do not want to cook for themselves. Akau jokes that his local-boy upbringing did not prepare him for the world of portion-controlled vegan, gluten-free or dairy-free diets, but he is learning.

For now, he says, the most important thing is to stay focused on his goals. When he gets down, he remembers something a favorite teacher once said to him. “If you can wake up every morning and make your bed, the rest of the day you’ll be good. It’s the consistency that will make all the difference in the end.”

Cori Talbott and her family:

The family makes creative use of their small living space so it does not feel so cramped. In fact, creativity in many forms helps them survive financially. One example is the regular swap meets that Cori has

with her friends: Everyone brings used

clothes to exchange. Photo: James Rubio

The Young Family

When people first step foot in Cori Talbott’s one-bedroom apartment in Kona, they are amazed at how cleverly she has arranged it to fit her family of four.

“I’ve learned to be crafty and creative,” she says, describing the bunk beds, shelves, hidden storage areas, lanai used as a dining room, and living room that doubles as a sleeping space and TV area.

“It’s not ideal but we’re saving at least $700 a month not moving to a two-bedroom place,” she says. “Besides, we’re really close as a family, and the kids are still little. They don’t need much of their own personal space yet.”

The 28-year-old Portland native moved to Hawaii Island nine years ago on a one-way ticket to visit her father. Today, she lives with her husband, 6-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son. She makes minimum wage as a waitress, working about 40 hours a week split between two places. Her husband makes $18 an hour as a banquet bartender for a hotel.

Both depend heavily on tips. “It’s feast or famine. If I’m not making at least $100 a day in tips, it will be a tight month,” she says.

Their expenses include $989 a month for rent, up to $215 for utilities, $115 for cable, $477 for car payments and about $200 for her and her husband’s mobile phones. Talbott is not sure how much they spend on food, but acknowledges they eat out once a week, with a bill for the four of them at around $100.

“We do feel financially stressed. We’ll go out and treat ourselves and buy things for the kids. And then the bill will come, and it’s like, how did we let this happen?”

Their children qualify for free health and medical coverage under Quest, the state’s Medicaid program, which is financed by federal and state money. But Quest does not cover Talbott and her husband, so they remain uninsured to avoid paying health insurance premiums. She says she is not worried. “I don’t ever go to the doctor,” she says, describing her preference for natural solutions.

For Talbott, the key to coping financially is creativity. She shops at thrift stores, compares prices online, gets email alerts from sites such as steals.com, and takes advantage of free shipping through Amazon Prime. When she goes to Target, she first looks for coupons on her phone’s Cartwheel app.

Instead of buying new clothes, she and her girlfriends hold regular swaps. “You bring all your used clothes, dump them together and everybody scavenges. It’s cute stuff, you know where it’s coming from and it’s free.”

Her network of friends also helps her save money on childcare. “They say it takes a village and it really does. If you move here without family, it can be difficult to not have anyone to pick up your kids if you’re late coming home from work. So it’s important to develop your ohana.”

Instead of getting all of her groceries at once, she goes to specific places at specific times for certain items. “Target has killer deals on some food, like peanut butter and carrots. I go to the farmers market on Sunday since they close on Monday and I can get a better deal on those days, like a whole box of bananas for $5.”

Growing vegetables also helps keep food costs down. “It seems silly but it all adds up. If we can save $600 a year on produce, that’s $600 in my pocket for something else.”

Growing vegetables also helps keep food costs down. “It seems silly but it all adds up. If we can save $600 a year on produce, that’s $600 in my pocket for something else.”

Despite all the work it takes to live within their means, Talbott insists her family does not feel like they are doing without. “I know that if we lived on the Mainland the same way we live here, people would describe us as poor. But I don’t feel like I’m sacrificing. We just live more simply. My kids aren’t asking me for iPads. They get to go to the beach after school. We may have a very small home, but that’s OK. It gets us out of the house.”

As for what’s next, she takes online classes to become a holistic health coach, and hopes that career allows more time at home with her children. The family is trying to save for a Mainland trip, which would be their first together. She also dreams of taking her children to Disneyland and, while it feels unrealistic to her at this point, her husband talks about buying a house to share with his father.

She has seen friends leave Hawaii for financial reasons, and knows they, too, would likely have a higher standard of living if they moved to a place like Portland. But, she says, they never consider leaving Hawaii.

“I could never go back, knowing that this existed,” she says, gesturing toward the ocean. “I just couldn’t, knowing I would no longer be a part of this. I get to look out and see this every day. That’s why I’m here. When you want something, you make it work.”

The Single Parent

As a single mother who does not receive any support from the fathers of her two children, Shannon Autrey makes ends meet with 14-hour workdays, help from her parents and public assistance.

Born and raised on Oahu, the 37-year-old moved to Michigan with her then-husband in 2000. After separating, she worked as a casino dealer, making $2,600 a month and easily affording the $600 rent for a two-bedroom place. “I found out that I could make a good life for my daughter. I didn’t need any help, I was comfortable,” she says.

By 2009, she was raising two children on her own and moved to Kona, where her parents had relocated. Today, she shares a small space in their home with her 14-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son.

Autrey had been working as an administrative assistant for $12 an hour, but recently switched to bartending. Although she earns minimum wage, the tips make it worthwhile.

“On a good night, I can make about $150 cash in hand. But to get there, I’m working 14 hours a day.”

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) provides $584 a month for food. Quest provides medical care coverage for her and both children.

“Being on these programs is just awesome. They are such big savers. A lot of people don’t take advantage of such benefits. They think that if you have a job you don’t qualify. My advice is to know what benefits you can get as a single mother.”

Shannon Autrey and family

Autrey and her two children live with her parents in Kona, which is the only way they can get by on her bartending wages, supplemented by support from SNAP (formerly food stamps) and Quest, the state’s Medicaid program. Photo: James Rubio

She emphasizes, however, her parents make it possible for her to live in Hawaii. She only pays $500 for rent and utilities to stay in her parents’ home. Family members pick up the children from school, take them to after-school programs and sports events, and ensure her special needs son gets to his appointments. She uses her father’s older car to get around. Although she buys most of her own groceries, family and neighbors often stop by with freshly caught fish and pork, as well as avocados and mangoes from their gardens.

“If you’re raised here, you’re raised with a strong sense of mana, or power. You take care of family. It’s automatic. It’s bred into you. You don’t think twice about that,” she says.

Despite her deep gratitude to her family, she insists this is not a permanent solution. “Living with family, there is a lot of meddling,” she admits, laughing. “I’m 37, so I don’t want them to be involved in how I parent. But they are going to get involved no matter what since we are under their roof.”

Rent in Kona, however, is beyond her reach at this point. “I just can’t afford a big enough condo on Alii Drive.” She is not considering areas such as Ocean View, which has much lower rents, because of the long commute to work and school.

She adds, “If there was a two bedroom in Kona going for $800, I could do that. But that would take magic.”

She has looked into Section 8, a federal program that provides rental assistance to low-income families. The waiting list in Kona is long, however, and new slots only open when families leave the program. Another challenge is that even with Section 8 subsidies, the rent for a big enough place in Kona was still too much on Autrey’s previous income of $12 an hour.

“I left my office position, which had great hours, for 14 hours a day as a bartender. Sometimes I don’t get home until 3 a.m. now, all because I couldn’t afford to get subsidized housing at my former job.”

Autrey has also investigated home ownership programs for low-income single parents, such as Habitat for Humanity, which helps people build homes on land they own. The barrier, however, is her credit score.

“I started with credit cards while I was in college. There was nothing major, just some late payments. Things just happened. And then my creditor sold my debt to third-party companies, who want me to pay them off in a lump sum. I can’t do that right now. So at this point I can’t qualify for a home loan because my credit is so bad.”

Autrey also struggles to provide for her children’s changing needs as they grow. At the end of the month, she is usually left with only about $100. Her daughter, an honor student and high school freshman, would like her own room and travel money to join her classmates on the debate team as they compete on Oahu. Her son wants an iPad and the latest video games.

“Money is continuously revolving in my wallet: It comes in, it goes out. There are no savings right now. We live check to check.”

Autrey senses she may soon be at a tipping point.

“I might have to move back to the Mainland, maybe a place like Michigan, where I can make more and live for less. It’s hard because my family doesn’t want that, and my kids are attached to their friends and grandparents. My son has been here since he was 3 years old, and he loves hunting, fishing and the beach. I don’t want to move them away from all of that.

However, the difficulty in making enough money to rent or buy her own home has persuaded her that to live in Hawaii long term, she first needs to leave Hawaii.

“I love Hawaii and I want to settle down here. But I think I will have to come back here with a chunk of money, a nest egg, in order to buy property. There is no way I can do that, starting off with what I can make here.”

Making Ends Meet

Despite working full time or more, the people in this article all live well below the median annual household income of Hawaii Island, which is just over $51,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. (See box below for each county’s median wage.)

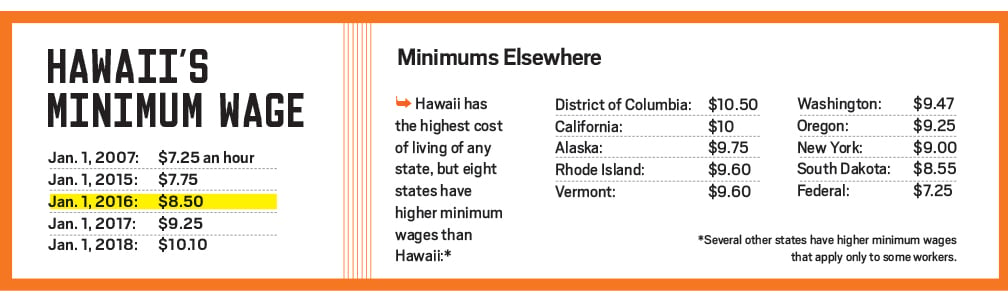

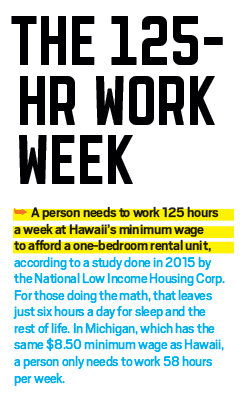

Hawaii’s minimum wage is mandated to increase gradually each year, reaching $10.10 an hour on Jan. 1, 2018. That will help, but it won’t lift every working person or working family in Hawaii out of poverty.

As Charles Akau IV, Cori Talbott and Shannon Autrey demonstrate, making ends meet while working for close to minimum wage requires discipline, creativity and resourcefulness.

“Families from a wide range of income levels make sacrifices daily based on their family’s needs and wants,” says Miles Yoshioka, executive officer of the Hawaii Island Chamber of Commerce.

A lack of affordable housing may be the biggest problem: even though housing on Hawaii Island is cheaper than on most islands, there is little that is inexpensive. “It will take the effort of multiple agencies, local and state governments to address this housing issue,” says Yoshioka.

Akau’s and Autrey’s experiences also highlight how credit card abuse can make it more difficult to get ahead even years after you stop using the cards. And not having a car makes it difficult to get to work – especially if you have multiple jobs – given Hawaii Island’s meager public transport system.

Some sacrifices people make to stay on the island have upsides. As Talbott says, no iPads mean more time with each other, enjoying Hawaii’s natural world. Other sacrifices, such as foregoing health insurance, may have more serious consequences.

Autry describes her children, especially her teenage daughter, as very understanding and not having a sense of entitlement. But asking her children to do without what they see other kids have, she acknowledges, is one of the most difficult aspects of living paycheck to paycheck.

“They want to see a movie. Or go to McDonald’s. Once in a while we’ll go bowling, but that’s a luxury. My daughter now wants her own room. She’s a freshman in high school, and she deserves it. I feel bad for her because she should have her own space. But I just can’t afford it. I have to say no to my kids all of the time.”