Business’ Biggest Secret

Dane Atkinson used to be the kind of startup CEO that board members praised because he attracted top-notch talent while saving money. Certain candidates were just not aggressive at negotiating their salaries, and he took advantage of that.

“It’s easy in tech to promise the future without being honest about what you’re giving people from an equity and salary standpoint,” he says.

One encounter, however, changed his perspective.

“While having dinner with an employee, I casually revealed that there was a salary gap between people with similar skills. It actually brought that person to tears, realizing they had been so mistreated. It was a shock to see their devastation. It suddenly dawned on me it’s not just about economics. It’s about how you value people.”

Today, his New York-based company, SumAll, is an early adopter and champion of salary transparency. That means every employee’s pay is visible to everyone else in the company.

Sunshine laws in states such as Hawaii dictate that public-sector salary ranges are available for anyone to view, and federal regulations require publicly traded companies and other regulated companies to reveal the compensation of top executives. But otherwise, the private sector is notoriously secretive about what people make. There is a deeply entrenched belief that revealing salaries causes bitterness, once employees see how widely pay can vary among those with similar roles.

A recent study by Payscale published in Harvard Business Review, suggests otherwise. Transparent conversations, the researchers conclude, can actually promote job satisfaction, even if those employees know they aren’t making as much as they might at other companies. A separate study, conducted by researchers at Tel Aviv University, concludes that keeping salaries secret is actually associated with decreased employee performance.

“We discovered that when employees are treated well and can talk about salaries openly, they are more resistant to being poached, even when they get higher offers from other places. They feel like we’ve decided to be in this boat together. You end up getting substantially reduced churn,” says Atkinson.

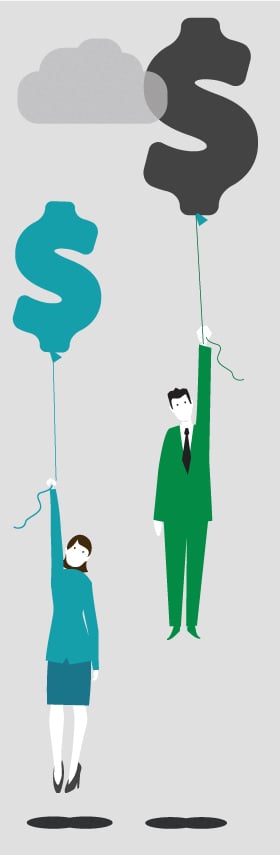

Increasing awareness of salary ranges has also been credited for shedding light on pay inequities. “Full-time women employees make on average 81 cents on the dollar compared to men. That ratio hasn’t changed much nationally since 2004,” says Ben Godsey, president and CEO of ProService Hawaii. “If you have transparent data, people can look at that and say there’s a problem. Then it becomes less possible for that gap to persist.”

Whole Foods Market has allowed employees to look up everyone’s salaries since 1986, but that’s a rarity among established corporations. However, the policy of salary transparency is gaining momentum among startups. These smaller companies, such as SumAll, have more freedom to create their company cultures from the ground up without working against entrenched norms.

The in-state human resource professionals interviewed for this piece acknowledge that, while salary transparency is generating an increasing buzz on the Mainland, it has not taken root among Hawaii’s businesses. If salary transparency champions such as Atkinson are right and this is more than just a fleeting trend, here’s what the state’s business leaders and employees should know.

MANY WAYS TO BE TRANSPARENT

Joel Gascoigne, co-founder and CEO of Buffer, makes $218,000 a year. “Happiness Hero” Hannah, based in the United Kingdom for Buffer, makes $66,002. And Steve, a systems engineer based in Taiwan, makes $98,175. Want to find out more, including the company’s revenues, equity formulas and fundraising details? You can look up all of that on Buffer’s website. Even painful challenges that most companies shroud in secrecy, such as cash-flow problems and layoffs, are fully shared on Buffer’s public blog.

“The radical transparency we use is not for everyone,” acknowledges Hailley Griffis, the company’s communications manager.

Not only has Buffer been transparent about its inner workings, the company has also been open about when transparency has not worked. After analyzing its own data, Buffer says it found it was still paying women less than men and, on average, promoting them less frequently.

“There is the subjective piece of the formula. If there is a higher percentage of men in senior positions, they are the ones making decisions around who to bring up to their level. It may not be a conscious judgment or bias, but people tend to gravitate toward those most like themselves,” says Lydia Frank, VP of content strategy at Payscale.

“You can’t say you’re addressing gender equity if you’re not addressing opportunity,” she adds.

While extreme transparency has attracted the most media attention, there is actually a spectrum of policies that companies are adopting. “Full transparency isn’t the right answer for every business,” Frank says. “For some, it may just mean talking about the fact that you have a process and are using certain data services to decide pay ranges, while regularly checking that pay is in line with the market. For others, it may mean just sharing some high-level philosophy that your company uses to decide pay.”

Human resource professionals in Hawaii have observed that while full transparency is not yet a widespread goal within Hawaii’s private sector, companies are increasingly interested in developing more systematic salary ranges based on experience and logical ways of communicating these to their employees.

Human resource professionals in Hawaii have observed that while full transparency is not yet a widespread goal within Hawaii’s private sector, companies are increasingly interested in developing more systematic salary ranges based on experience and logical ways of communicating these to their employees.

“Hawaii is more focused on employers developing fair and appropriate pay bands, and educating their employees on that,” says Godsey of ProService. “So if you have these skills, an employer can say that your pay will be 35k to 45k. If you want to make more than that, you are going to have to have more skills. People want to educate their employees on these pay bands.”

“When you have that consistent logic, it makes the manager’s job much easier to do. You can explain to people why they fall in a particular band.”

But what about the kind of transparency that Buffer exemplifies? Cathy Keaulani, manager of surveys and compensation services at the Hawaii Employers Council, wonders whether Hawaii employers are ready for this type of radical honesty.

“In Hawaii, we have a culture that’s family oriented and, because of that, our preference is to not make people feel uncomfortable. Many times at work you might be talking to or about someone related to you, like an uncle. And that can be a challenging situation,” Keaulani says.

MORE LEVEL PLAYING FIELD

Jennisen Svendsen spent two decades working in Los Angeles’ cutthroat entertainment business. Despite her experience, she was never confident she was making as much as she could.

Jennisen Svendsen spent two decades working in Los Angeles’ cutthroat entertainment business. Despite her experience, she was never confident she was making as much as she could.

“I felt like I wasn’t powerful at negotiation in this male-dominated business. It’s that feeling that it’s a guys’ club, and you just don’t know where you fit in. And when pay is secret and the people who make those decisions may have all gone to college together, you don’t know if the salary decisions they are making are completely fair.”

When she interviewed at Chewse, a startup that provides office meal plans and deliveries, she wasn’t sure what to make of its open pay policies.

“My first thought was, is this a trick? Does it take any power away from me?”

Those concerns dissipated when she met CEO and co-founder Tracy Lawrence, who brought in a salary scale that detailed the pay associated with different roles, each requiring a different level of experience.

“We don’t negotiate against a black box, in which we make you an offer, and the candidate then wonders whether they should ask for five grand more. From day one I communicate that, to be at a certain level, you need to do X, Y and Z,” says Lawrence.

Her approach was largely motivated by the pay inequities she observed as a CEO. The federal Equal Pay Act and Title VII explicitly ban the unequal treatment and compensation of female employees. Nonetheless, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, women with full-time salary or wage jobs in the U.S. make, on average, 81 cents for every dollar that full-time men make.

“As a female founder, I noticed when I started to hire that women weren’t negotiating as hard for their salaries. The system favored masculine negotiation skills, and I ended up lowballing women. And it infuriated me,” says Lawrence.

For candidates such as Svendsen, it was a relief not having to negotiate while she was uncertain about what others in the company earned. “All that anxiety of how much I’m going to make went away when I realized the CEO had put as much work in it as I had, and she’s looking at it in a fair way. It made me feel like I was getting paid for what I’m worth, and it made me feel like there was opportunity for growth.”

Svendsen adds, “I have friends who work in studios that are heavily dominated by guys and their power-play scenarios, and they think pay transparency could relieve so much pressure. It becomes a culture of ‘Let’s talk about it,’ versus ‘We’re doing battle.’ ”

CULTURAL SHIFT REQUIRED

Jindou Lee, CEO and founder of HappyCo, found out the hard way that you can’t simply copy and paste another company’s transparency formula. Having heard of Buffer’s success, he adopted its publicly available salary calculator, only making a few adjustments before applying it to his company.

“We found it was good when we were reasonably small. As we started to add more headcount, the calculator didn’t quite work anymore.”

One reason was HappyCo’s employees are all around the world. The formula it adopted did not account for different salary expectations in places as diverse as the U.S., Australia and India.

Beyond that, Lee acknowledges, his company had not taken the time to develop clear definitions of roles such as mid-level engineers. As the company grew and roles changed, there was no easy way to figure how the formula should adjust.

“We used the Buffer salary guide and just tweaked it,” Lee says. “What we should have done was base it on our own organization and built it out from our own perspective rather than adopting someone else’s methodology.”

Cathy Keaulani of the Hawaii Employers Council cautions companies that much work needs to be done before sharing any salary information.

“Many companies may not have everything organized when it comes to compensation programs and policies. They may not feel comfortable that all jobs are competitive with the market. They may not have gone through a study to gain an understanding as to how base pay in their company compares to the external market. The process of understanding the company’s compensation philosophy, how they evaluate jobs, rank jobs among each other, and define the internal value of jobs to the organization must be put in place first. And, of course, there’s educating managers on how to communicate how decisions are made and how to support employees with understanding their compensation,” Keaulani says.

Lee admits he underestimated how critical it was to have someone within the company who focused on building a culture of transparency. “I think a full HR role is necessary in every organization, regardless of your transparency layer. You need someone who is ultimately accountable for employee well being, and how all these topics are handled. But, unfortunately, when you’re small, it falls on the founder and CEO.”

In addition to the nuts and bolts of developing a transparent system is the higher-level question of whether it makes sense within the company culture.

“In my work, I get to know organizations, gain an understanding of how their leadership operates and thinks, and how they communicate. A lot has to focus around trust, and again that goes back to culture. If you have an open culture and people feel trust, they will understand it’s coming from a good place. But others are just not ready, and so employees may end up seeing it as more complicated and confusing,” says Keaulani.

Chewse CEO Tracy Lawrence agrees. Although companies approach her all the time for advice on going transparent, she warns them that, just because it has garnered a lot of buzz, does not mean it is for everyone. “When I’m fundraising, I give the team an update every week on how that’s going. Some CEO’s don’t talk about this. Communication about compensation needs to align with your style of company. If you’re a secretive organization, this will not work for you.”

Lee, who tried salary transparency and decided, for now, it wasn’t right for HappyCo, stresses that transparency should not be considered a trend to be adopted and discarded like a fashion statement. “I see this a lot in Silicon Valley: Companies say they’re going to be transparent. But you can’t just ‘be’ transparent. It’s either in your DNA or it’s not.”

MILLENNIALS EXPECT TRANSPARENCY

Not surprisingly, the culture of transparency is championed by the younger generation, which is less likely than Gen X or Boomers to think of salary as a taboo subject.

“Growing up with information at their fingertips, Millennials have a desire to know. For them, not knowing is a place of uncomfortableness. If they can’t get information, they question why,” says Ryan Kusumoto, who is on the board of directors at the Hawaii chapter of the Society for Human Resource Management.

At a recent conference, Buffer communications manager Hailley Griffis met a young woman and man, both around her age. They each shared how much they made. The woman, who made the least, wondered aloud if she was getting paid too little, and ended up getting advice from Griffis on how to find out what she should be making.

“I’m comfortable talking about salary and money. I’ll bring it up in conversations with people, to the point where I almost have to scale it back,” Griffis says, laughing.

Millennials are also among the primary users of a growing set of online resources aimed at helping people understand what they should be earning. LinkedIn, Glassdoor and Payscale all offer tools for evaluating salaries for particular job titles in specific markets.

Griffis has found that transparency among those in her generation also leads to better support systems when things do not go well. When Buffer announced layoffs and was publicly transparent about the cash-flow crisis behind its decision, the support was tremendous, with companies immediately offering to interview the people who were let go.

Griffis has found that transparency among those in her generation also leads to better support systems when things do not go well. When Buffer announced layoffs and was publicly transparent about the cash-flow crisis behind its decision, the support was tremendous, with companies immediately offering to interview the people who were let go.

Lydia Frank of Payscale agrees that, when it comes to the relationship between employers and employees, the Millennial generation has changed the dynamics. “For years, employees didn’t feel like they had a way to move the needle and employers had all the power. People felt uncomfortable talking about money. But Millennials have had a huge influence on the expectation that employees should know and have access to information. Beyond pay, they want to know more about business. Why shouldn’t I know? Why can’t I talk to my co-workers about it? With Millennials, many things have been upended.”

WHAT’S TRANSPARENCY’S FUTURE?

Todd Zenger, professor in the University of Utah’s Department of Entrepreneurship and Strategy, isn’t convinced that transparency is right for all companies. He argues that pay transparency could end up making it harder to reward exceptional people, who are not easily measured by objective values.

“One of the big reasons it’s being pushed is that it could address the gender pay gap. And I agree, it certainly does address that. But, at the same time, it’s likely to tie your hands in your ability to link pay to anything but truly objective performance, which you may have very little of.”

Zenger adds, “Full transparency is easy only if you use objectively measurable values, like education. It’s easy if there’s a formula. But then we also have this subjective performance assessment, which can include your peers’ evaluation. Then it gets murkier and messier.”

While awareness of the potential benefits of salary transparency has grown, the numbers of companies actually practicing remains just a handful. Lydia Frank of Payscale says there is currently not enough data to solidly assess its long-term impact. Nonetheless, she says, whether a company adopts a model like Buffer’s may not be what is most important.

“Salary transparency isn’t necessarily better. What’s important is taking steps toward helping employees understand their career path and giving them more power to know what to do to get there. That creates an employee who wants to stick with the company,” Frank says.

For Chewse CEO Lawrence, transparency is one of many ways of achieving a certain kind of company culture, which is the ultimate goal. “We call ourselves the love company. We treat our employees like humans, and that means authenticity, and having difficult conversations openly. We want people to bring their whole hearts and selves to work. Salary transparency is just one tool to demonstrate that authenticity.”