Opioid Nightmares in Paradise

PART 1:

The journey of an opioid addict begins with a pill or two that creates a glorious euphoria. Then begins a slow descent until you eventually hit a hellish bottom unique only to you. And then, maybe – if you are still alive – you begin the never-ending marathon of recovery.

HOW ADDICTION BEGINS

A car accident in high school left him with a broken jaw. He was prescribed Percocet, a narcotic that numbed his pain and created a sense of euphoria. Each time he asked for a new prescription, his oral surgeon complied.

“Between going to school, working and everyday life, the pills made me feel better, faster and stronger.”

When Edward’s oral surgeon finally stopped giving him more, he stood outside pain clinics and offered people cash for their bottles. This continued after he moved from the Midwest to Hawaii Island, where he developed a reputation up and down the Kona Coast as the guy who bought so many pills, there was nothing left for anyone else.

He even developed a knack for spotting new sources. “Opioids have an effect on eyes and they make your nose itch. If I’m at the grocery store and I see someone scratching their nose a lot, chances are they use like I use. And that means they’ll know someone who’s selling.”

He remembers being under a lot of stress one Thanksgiving Day. He had run out of pills, and none of his regular providers had anything for him. Desperate, he approached a homeless camp, offering coffee for information on other dealers.

“It was then that I started doing heroin. I bought $1,000 worth of it that day. And from then on, spent $1,000 every month on it.

“I had no idea that getting my wisdom teeth pulled way back then was going to change the course of my life like that,” says Edward, who like other recovering addicts quoted in this story asked that only his first name be used.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports sales of prescription opioids have quadrupled since 1999, though the amount of pain Americans report has not increased at the same rate. Since 1999, there have been over 200,000 deaths related to opioids. In 2016 alone, there were over 42,000 opioid-related fatalities, surpassing the number of people who died from breast cancer. And by some accounts, these official numbers are low because they only reflect reported deaths.

How did we get here? How does someone like Edward go from taking legitimately prescribed medication after minor surgery to becoming a full-blown addict?

Board certified psychiatrist Dr. Gerald McKenna says that in the 1980s, there was growing concern that physicians were undertreating pain, and by the mid-1990s, the American Pain Society had begun pushing the concept of pain as a fifth vital sign in addition to blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and body temperature.

“A kind of edict came down saying we had to treat pain adequately. It wasn’t really specific what the ‘adequately’ meant, but it had to be to the satisfaction of the patient,” says McKenna, who is the founder of McKenna Recovery Center in Lihue.

“A kind of edict came down saying we had to treat pain adequately. It wasn’t really specific what the ‘adequately’ meant, but it had to be to the satisfaction of the patient,” says McKenna, who is the founder of McKenna Recovery Center in Lihue.

This led to practices such as asking patients to rate the severity of their pain on a scale. “People became very focused on pain, and their expectations changed from ‘pain is part of life’ to ‘I shouldn’t have to experience pain.’ Whether it was pain from arthritis or a carpenter overworking and having joint issues, all of a sudden, everyone wanted to get their pain treated,” says Dr. Norman Goody, medical director of Hospice of Kona.

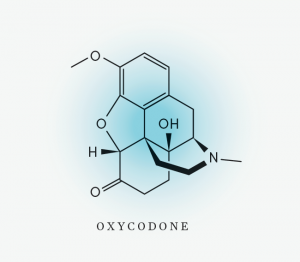

In 1996, Purdue Pharmaceuticals began marketing OxyContin, an extended release synthetic painkiller. Two heavily cited but now debunked studies gave credence at that time to the argument that patients who are prescribed opioids for pain treatment rarely develop addictions.

Physicians who had never worked with opioids began prescribing them not only for acute pain, but also for chronic issues such as backaches. And people who had little to no experience with addiction found themselves increasingly dependent on the pills their trusted doctors were telling them to take.

“We’re talking about baseball coaches and the auntie who fell and broke her hip, got a prescription, became addicted, and is now having issues around that. It’s people we normally wouldn’t assume could become addicted,” says Edward Mersereau, chief of the state Department of Health’s Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division.

As people developed tolerance, doses got higher. People began dying from opioids because the drugs slow down breathing and suppress neurological signals to the heart. “We all have an opiate dose that will kill us but we don’t know what that dose is. It’s different from person to person,” explains McKenna. “A person could be taking high doses for back pain and one night, before bed, the pain comes back, so they take another handful. And they just don’t wake up after that.”

WHERE’S THE SUPPLY

While working in a clinic on Hawaii Island, Dr. Martyna Bednarczuk saw how easy it was for people to obtain opioids from one particular physician. He had become well known on the island for his lax prescription practices.

She remembers a woman with chronic back pain who always came in early for a refill. At one point, it was clear she had taken a month’s worth of Percocet in just four days and was showing signs of severe addiction.

“He would never say to patients, let’s think about weaning you off. He thought, well if that guy is weaned off, I lose a patient and I lose an income,” Bednarczuk says.

The FBI and the Drug Enforcement Administration have been investigating physicians, like the one Bednarczuk worked with, who are indiscriminately overprescribing. They are also cracking down on pill mills, or shady clinics where people can get opioid prescriptions for cash without being properly examined. But it can sometimes seem like a game of whack-a-mole. Take out one source, and other innovative strategies pop up.

One user named Will describes how his friends go to open houses in wealthy neighborhoods such as Malibu, where rich people own part-time homes but often forget what they leave there. While one person distracts the real estate agent, the other goes through the medicine cabinet.

Will now lives on Maui but grew up on the East Coast, where he used to look for doctors fresh out of medical school. Knowing they likely had student debt, he would offer them $500 to write him prescriptions. If they hesitated, he would offer to get an MRI done. By bending his foot a certain way, he could fake a pinched nerve in his back.

“It was easy during the winter on the East Coast. I could just say I slipped on the ice shoveling snow for my grandmother,” he says.

Ann describes her younger self as a popular high school cheerleader from a middle class family. Unbeknownst to her parents, she started using a variety of drugs when she was 15, and became a drug dealer to pay for the habit.

When she moved to Hawaii Island, she learned the terminally ill are a great resource. They often get prescriptions for large quantities of opioids to manage their pain. Ann would convince them to sell her their pills and use the cash to buy meth, which was cheaper, so they could pocket the profit. “They’d get so high on meth, it didn’t matter. They didn’t feel the pain anymore,” she says.

HOW IT ESCALATES

Paul was a Green Beret and could not wait to be deployed to serve his country. But one evening, Paul was in the car when a friend drove into a ditch near Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and died. Paul was left with a broken back and no chance to ever walk again.

While hospitalized, Paul was put on OxyContin. Eventually, he started pretending to swallow the pills the nurses gave him. When he was alone, he would secretly cook them in a spoon and shoot them into his IV line.

“At that point, it didn’t matter that I was paralyzed, it didn’t matter that I had to pee through a catheter and I couldn’t feel my legs anymore. All those worries were taken away.”

After getting out of the hospital, Paul got clean and, using his GI Bill benefits, eventually graduated from law school in the top 10 percent of his class. He was offered a job at a prestigious law firm in Washington, D.C.

But while having minor surgery, he was given hydromorphone. “The stress about the litigation I was working on and whether I was on partner track and whether I was dating the right girl, all of it was taken away. And I relapsed.”

For the next year, he lived a double life, working at the law firm by day and shooting heroin at night.

Four out of five heroin users get their start by misusing prescription opioids, according to the American Society of Addiction Medicine. Heroin is cheaper and often more readily available to buy on the illicit market.

“At the time, OxyContin was going for about $80 for an 80 milligram, whereas a balloon of heroin was $10, and it probably equaled three or four OxyContin 80s,” Paul says. “And the Mexican cartels made it so easy. You’d make a phone call and 10 minutes later there’d be a guy in a parking lot.”

Once prescription opioid users transition to heroin, new dangers arise. Gary Yabuta, executive director of the Hawaii High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, explains that heroin in circulation today is vastly different from what was available in the ’60s and ’70s. Back then, the quality was stable and predictable.

Today, heroin is often laced with varying amounts of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50-100 times stronger than morphine, that is typically used for treating severe pain in advanced cancer patients. And illegally made fentanyl from China has flooded into the U.S.

Heroin users now expect stronger products. “Today’s addicts are pushing it to that point where death is just a minute microgram away,” says Yabuta.

TURNING IT AROUND

Ann’s moment came when she realized her Hawaii Island home was no longer safe for her young son. Strangers had started following her there, demanding her stash. Some had become so aggressive, she had to sic her dog on them. “Being such a small island, we’re all connected. My name started getting out there, and eventually it blew up and got out of control.”

Edward’s moment came when he could no longer hide his addiction from his partner. He had lost a lot of weight, was bleeding “from places you’re not supposed to bleed from,” and had developed such swollen lymph nodes that everyone around him feared he had cancer.

For Paul, it was losing his short-term memory after an all-night heroin binge. “I was not there, I was just gone. I thought, ‘Now I’m brain dead and paralyzed. I might as well just burn it down. Like there’s no coming back from this one.’ ”

Each experienced a turning point that was the beginning of their commitment to get better. But how and when does this happen?

Everybody’s bottoming out looks different, says certified substance abuse counselor Bria Hicks, who works at the Hawaii Island Recovery Center. There can be external drivers, such as running out of money, that may drive a person to seek help. And there can be internal drivers, such as the desire to retain custody of a child, that will get a person to stick with recovery. But, Hicks says, it is impossible to predict what each person’s rock bottom will look like.

“You could be homeless or you could be living in a mansion. It’s the bottom to you if you are experiencing so much despair that you’re asking for help, and receptive to recovery.”

The most important thing for Ann was that when she was ready, there was a place for her to go. “When you’re so desperate, and you don’t want to do it anymore, and you make that call, you need someone to call you back or answer the phone – not wait for days for a call back or months for a bed space to open up. A lot of people don’t want to do it anymore but it takes so long for help to come, that they end up going back.”

LONG ROAD TO RECOVERY

Katherine, a woman in her 30s, is wearing a thick sweatshirt while being admitted into a recovery program. Despite the muggy Kona weather, she has the hoodie pulled tight around her head. She can barely walk on her own, her face is contorted with pain, and she shakes uncontrollably. Bria Hicks describes the withdrawal that Katherine is going through as “getting the marrow pulled out of your bones.”

Katherine had been in a car accident as a teenager and suffered severe back injuries. Her physician had prescribed fentanyl, keeping her on it for a decade. When he suddenly stopped her prescription, she turned to heroin.

Later, Hawaii Island Recovery’s medical director, Dr. Stephen Denzer, says that for people like Katherine, Suboxone can make the difference between recovery and relapse. Suboxone is a combination of two drugs. The first, Buprenorphine, is actually a mild opioid. It will, Denzer explains, minimize withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

The second, naloxone, reduces the pain-relieving and euphoric side effects of opioids, so Katherine can get back to what it feels like to not be high but also not be in withdrawal. Naloxone also makes it very difficult to overdose on Suboxone, lessening the potential for abuse.

But Suboxone is not a miracle drug. It can only play a part in the recovery process.

“You still need to address the underlying issues that caused the addictions in the first place, whether they were emotional issues or personal problems with family or anxiety. If you’re just giving the meds and not addressing the issues, a person isn’t getting any better,” says Hospice of Kona director Goody.

That is where therapist Zahava Zaidoff enters the picture. She is leading a session at the Hawaii Island Recovery Center and on this day, seven people are in recovery. The oldest is in his 70s; the youngest is just 18.

Zaidoff draws a circle in the middle of the board with the word “problem,” and prompts the group to discuss their coping mechanisms. Radiating out from the middle circle, she writes down their answers: food, work, sex, TV, exercise, isolation, partying. And of course, alcohol and drugs.

“Most of you didn’t come here to get help for this.” She points to the middle circle. “You came because one of these solutions,” she says, referring to all of the coping mechanisms surrounding the middle circle, “has become the problem.”

“Because we’re so focused on the drink and the drugs, we forget to talk about the fact that they are actually a coping mechanism to deal with your original problem. And even if you stop doing drugs, it doesn’t mean you won’t move on to one of these other things if you don’t focus on the real problem.”

There are nods and groans in the group as people acknowledge the hard work in front of them.

“Let me be honest with you,” Zaidoff says, putting her marker down and looking long and hard at each person. “You will never find anything that works as quickly as drugs and alcohol. Never. There’s no tool I can give you that will work faster.”

“You will, however, find things that work longer and are healthier for you. And I’m here to teach you that.”

One thing Zaidoff and other counselors stress is the importance of deeply connecting to others. Later that week, I attend an open meeting with Narcotics Anonymous, which is based on the Twelve Steps philosophy. It is held under a pavilion at the Old Airport Beach in Kona, against a brilliant sunset backdrop. Over 30 people had gathered around a few picnic tables. A man covered with tattoos sits next to a young mother carrying her toddler, who sits next to a surfer dude.

One person announces that he is 30 years sober that week. Another says she has made it for 24 hours, and then begins to cry. Most people share something about what they are experiencing. There are no responses given to each other, only listening. And sometimes empathetic laughter. Every person, no matter how long or short their sobriety has been, begins by stating their name and the phrase, “I’m an addict.”

Edward, who had once scoured the Kona Coast for opioid sellers, says that Twelve Step has helped keep him clean for over nine months now. “These are friends I can be honest with. It’s helped me break down some walls because of the unconditional love we get there. I was living a double life. But here, we’re all the same. We’ve all made mistakes. We’re all recovering.”

By the end of the meeting, it’s dark except for the moonlight. Everyone stands in a circle in the sand, holds hands, and recites the serenity prayer. Then people drift off in different directions.

I find myself wondering which of them will be successful in their recovery. But then I remember something Bria Hicks had said – that we just don’t know and we shouldn’t try to predict based on our stereotypes of addicts.

This makes me think about Paul, the former Green Beret and D.C. attorney, who has gone in and out of relapse and recovery so many times. He laughs when he describes his life as a “sordid story.” I don’t know if he will stay sober from now on, and he tells me that in all honesty, he doesn’t know either. What I do know is that the last time we spoke, he was clean, working in Kona, going to meetings and living in a drug-free house.

“I’ve seen so many people die from drug addiction. But I’ve also seen the Twelve Steps raise the dead. And I thought, well, if it’s worked for me before, it can work for me again,” Paul says.

“I would like to say that I’ve learned my lesson. But what I know is that by this point in my life, it’s a marathon. It’s not a sprint. And despite it all, I still have hope that I can have a chance at life again.”