Solutions to Hawaii’s Opioid Nightmares

PART 2: “For Once it’s Good to be 50th”

The opioid crisis in Hawaii is much milder than in other U.S. states, though it has surged here in recent years. Here’s what is being done locally to reduce the problem.

Every day in the U.S., an average of 115 people die from opioids, a class of drugs that includes prescription pain pills such as OxyContin plus heroin and fentanyl. The White House says the opioid epidemic costs the nation more than $500 billion a year, and it has been declared the worst public health crisis in our country’s history.

Hawaii’s numbers remain small compared to the rest of the country. In 2016, the state had 5.2 opioid-related deaths per 100,000 people. The rate was 43.4 in West Virginia and 32.9 in Ohio, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“For once it’s good to be 50th,” says state Sen. Josh Green, who recently helped pass legislation requiring prescribers and doctors to go through informed consent with patients receiving opioids. Nonetheless, he emphasizes this is not the time to be complacent.

“About three years ago, the crisis started to surge in Hawaii. When we saw that deaths related to opioid overdoses had exceeded car accident deaths, that was a wake-up call that even in the best state, we have work to do,” says Green, who is also a physician.

Kauai’s County Council recently announced that it is suing the prescription drug industry, joining more than 80 other cities and counties seeking to hold companies responsible for the costs related to the epidemic.

Lawsuits, however, can take a long time to resolve. What else is being done to make sure Hawaii stays at the bottom of the opioid rankings? In this story, community, state, federal and medical leaders outline their efforts.

BREAKING DOWN SILOS

In December 2017, Gov. David Ige released the Hawaii Opioid Initiative Action Plan. The plan was based on input from physicians, first responders, pharmacists, academics, community outreach leaders, judges, police and drug enforcement officers. It’s committed to an integrated approach in six areas:

- modernizing access to treatment,

- improving prescriber practices,

- better data collection,

- improved community-based programs,

- increasing pharmacy-based interventions, and

- coordination and support for law enforcement and first responders.

“I’ve been in the field 25 years and I have never seen such a cross sector, interdisciplinary approach to addressing such a complex problem,” says Heather Lusk, executive director of the Hawaii Health and Harm Reduction Center, and one of the co-chairs of the initiative.

One immediate outcome is a plan to set up prescription drop boxes at over a dozen police stations, where people can bring unused prescription drugs any day of the year instead of leaving them at home or flushing them down the toilet.

“A lot of times those expired or unused prescription drugs are used in a dangerous way, either because children get a hold of them or they just get into the wrong hands,” says Lt. Gov. Doug Chin. “Being able to turn in these drugs and get them out of our medicine cabinets means not only are we protecting the environment but making sure we have fewer opioids being used in ways they were not prescribed for.”

The lieutenant governor’s office will announce when the boxes are available for public use, possibly in August.

Another new program is called LEAD, Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion: When a police officer finds someone committing a minor offense stemming from substance abuse, instead of arresting the person, they can contact an outreach worker who will get the person addiction help.

“When law enforcement entities like the police are saying to me that we recognize we can’t arrest our way out of these issues, that’s actually really exciting to hear,” says Edward Mersereau, Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division chief at the state Department of Health. “What they are saying is that we know we have to do our job, but that’s not going to cut it for solving this issue. Public health needs to work in conjunction with law enforcement and vice versa.”

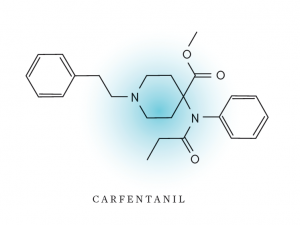

A NARCOTIC SO DANGEROUS THAT PARAMEDICS MUST WEAR MASKS

Hawaii Island Fire Department EMS Capt. Chris Honda and his team are preparing for what might be the next big thing in illegal narcotics: carfentanil, a morphine derivative that is 5,000 times as potent as heroin.

Carfentanil is used primarily for sedating large animals, but illicit forms from China have been found on the Mainland mixed with heroin.

There are no documented cases of it in the state so far, but because it is so deadly, Honda and his emergency medical services team would need to use protective masks and protection for their eyes and mucus membranes if they ever had to deal with it.

“It’s a safety issue for our responders. We’re going through a lot of training and gathering information, staying involved with different agencies on how to control it while keeping our responders safe.”

DESTIGMATIZING ADDICTION

Leilani Maxera has seen how stigma kills. “If people are embarrassed to tell others they use, they are more likely to overdose because they are hiding it. The stigma makes people ashamed to get help. I want to tell them, there’s nothing to be ashamed of,” says the outreach and overdose prevention manager at the Hawaii Health and Harm Reduction Center.

Changing everyone’s view of addiction is a fundamental step that health care workers and community leaders are taking to counter Hawaii’s opioid problem. That includes shifting the common perception that addiction is a personal failure to the scientifically backed fact that it is actually a disease.

Dr. Kevin Kunz of Kona, a specialist in addiction medicine, explains: “We can begin with language. We no longer call patients with Hansen’s disease lepers. Opioid use disorder is a medical disease. It’s not a personality disorder. It’s not a moral problem. It’s not even a behavioral problem. Although it can cause problems in all those areas, it’s actually a brain disease. You put drugs in the brain, the brain doesn’t work right.”

Treating addiction as a disease means creating comprehensive treatment plans, which may include medication, behavioral therapies, participation in communities such as Narcotics Anonymous and monitoring over time.

“Think of it like diabetes. We don’t say, ‘You’ve got diabetes, here’s some insulin, good luck to you.’ We watch their sugar, we see how they’re doing, we measure their weight, we talk to them about their life, their diet and their exercise,” says Kunz.

Due largely to Kunz’s work, in 2015 the American Board of Medical Specialties officially recognized addiction medicine as a subspecialty. That puts it on the same standing as other subspecialties like cardiology, anesthesiology or sports medicine.

Obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Tricia Wright is working with others to establish an addiction medicine fellowship in Honolulu. They have identified training sites and experts willing to teach and are currently securing funding sources.

The need is imminent, says Wright. “The majority of addiction medicine providers in the state are over 50 years old, and half are getting closer to 70. If we don’t have new people being trained, we won’t be able to continue to provide excellence in addiction coverage.”

Although the establishment of a medical specialty is not a quick fix to the opioid crisis, Kunz argues that not only will it save lives, it will save the state money. “If you had a camera at a large integrated system like Queen’s or Hawaii Pacific Health, you’d see a pattern of people with substance use coming in over and over and over again. If you don’t treat the addiction, they’re going to be back with more complications.”

STREAMLINING THE PROCESS

If someone needs substance abuse treatment, do you know where to call?” asks Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division chief Mersereau.

“That has been part of the problem – there’s no statewide coordinated effort to make resources readily accessible and have the community know where to access that.”

In response, Mersereau’s division is spearheading a website where people can get information about treatment and ask questions. The division is also piloting an initiative called Coordinated Entry for Substance Abuse Treatment: one centralized number for health care workers to call to get the right referrals for their patients, whether that be an empty bed at a recovery center or counseling.

“I’ve been in this position for two years now, and one of the things I recognized is that the system is very fragmented. For example, the substance abuse system is siloed off from the medical care system. We will start by maximizing and defragmenting the resources that we have, linking them so they are more effective,” says Mersereau.

The prescription drug monitoring program, a state-run database that tracks controlled substance prescriptions, is another tool that is centralizing information that was once disparate. It allows pharmacists to see if someone is doctor shopping, getting multiple prescriptions and filling them at different pharmacies.

Pharmacists can then use these occurrences to reach out. “The physician-pharmacist component is an integral connection piece. The physician has the opportunity to say, ‘I didn’t know that. Cancel it.’ Anecdotally I’d say most physicians are happy when pharmacists call and let them know about aberrant behavior. It’s like a breath of fresh air to have that conversation. And it protects the physician too,” says Chad Kawakami, assistant professor of pharmacy practice at UH Hilo.

He sees opportunities for pharmacists to play a more integral role in preventing drug abuse and overdose. He describes the perfect scenario in which pharmacists are integrated into care teams on site at medical offices to work directly to educate, counsel and monitor patients whose opioid use is chronic. While this is not yet the model in the private sector due to the way insurance coverage is structured, it has been implemented by the VA.

“If I had to make one main point, it’s that pharmacists are a very critical piece in this puzzle. And I think our training, education and accessibility are critical in combating opioid abuse. The health care system has these different tools, and pharmacists are another tool in the toolbox. Let’s utilize all of the tools better,” says Kawakami.

EMPOWERING COMMUNITY RESOURCES

Honda, the Hawaii Island Fire Department EMS captain, and his team regularly save people who have overdosed on drugs. And the people being saved come from all walks of life: rich, poor, young and old.

“Many people assume they are suicidal when they overdose. But we all have friends and family who are fighting things like cancer and are on narcotics. A lot of times it’s an accidental overdose. They just don’t realize the potency of the narcotics they are using,” he says.

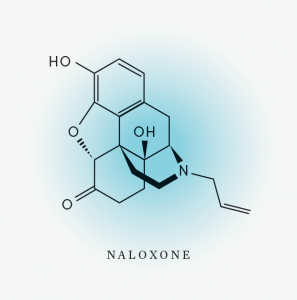

He and his team are trained to know when someone has overdosed specifically on opioids. “One of the signs is that their respiratory rates will decrease to the point where they might not be breathing. If we get there fast enough and they still have a heartbeat or pulse, the naloxone can bring them back pretty quickly,” Honda says.

He and his team are trained to know when someone has overdosed specifically on opioids. “One of the signs is that their respiratory rates will decrease to the point where they might not be breathing. If we get there fast enough and they still have a heartbeat or pulse, the naloxone can bring them back pretty quickly,” Honda says.

Naloxone is a medication used to block the effects of opioids. When administered immediately to someone who has overdosed, it can restore breathing within three minutes. Since 2016, the Hawaii Health and Harm Reduction Center has distributed over 1,000 doses.

“I’m happy to report that since then, we’ve had 70 opioid reversals in Hawaii,” says Executive Director Lusk.

A bill passed by the state Legislature and sent to the governor for his signature would increase awareness of and access to naloxone by allowing pharmacists to prescribe it to anyone they see come in who they believe could be at risk, as well as to any family members and caregivers who want to be prepared.

“I say to folks when I train them on how to administer it that they may not use drugs themselves but they want to be ready if something happens. It’s very touching for me when family members call and say they want to have naloxone so they can be there for loved ones,” says outreach and overdose prevention manager Maxera.

FIGHTING TRAFFICKERS WITH KNOWLEDGE

Do not underestimate drug traffickers, says Gary Yabuta, executive director of the Hawaii High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program. “They are extremely business savvy. They understand drug flow the way legitimate businesses understand the stock market. The transportation mechanisms are incredibly sophisticated.

“No wall is going to stop it.”

John Callery, Drug Enforcement Administration assistant special agent in charge, explains that while illicit drugs like heroin and methamphetamines commonly enter Hawaii through shipping containers, traffickers are increasingly sending them through the Postal Service and FedEx.

“They’ll send 70-80 parcels over a week, each one containing 100-200 grams. Each one is not a lot, but when you add it up, it becomes significant,” says Callery.

To fight these traffickers, Yabuta says, law enforcement must become more integrated. To help achieve that, the Hawaii High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area was established in 1999 to provide assistance to federal, state and local agencies. The goal, he says, is to share information about traffickers’ assets, organizational structure and links to other groups.

“What we’re trying to do is nurture that environment by forming multiagency analytical support. This is the same type of support necessary for fighting terrorism in today’s world,” says Yabuta.

Callery is also focused on investigating and shutting down places that distribute prescription opioids inappropriately. He has conducted audits of pharmacies and undercover investigations of doctors who have been called in as suspect. While the number of physicians he has to investigate in Hawaii is low compared to crowded cities like New York, “you can see the amount of damage just these dozen or so doctors have done,” he says.

Callery stresses how important it is for people to report instances of opioids being prescribed inappropriately. “My promise to the people of Hawaii is that we’re not going to stop. We’re going after every doctor and every pharmacy we have information on. We’re going to shut them down.”

MAKING PROBATION WORK

Retired Oahu Circuit Judge Steven Alm recognized years ago that regular forms of probation were not helping drug addicts get better. For one thing, they were rarely fair. Probationers could miss appointments or give dirty urine tests with no immediate consequences because judges and probation officers did not want to send them to prison for minor issues. But when sanctions seem delayed or arbitrary, Alm says, there is no leverage to get people to show up and stay sober.

“Then I got an idea for a kind of good parenting concept. If you grow up with parents who care about you, when you do something wrong, they do something about it immediately. That’s how you learn to tie together a bad choice with a consequence,” he says.

That was the insight that started Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement program, which has now been replicated across 32 states. HOPE was created by Alm in 2004; it imposes proportionate jail time swiftly and with certainty as a sanction for positive drug tests or other probation violations.

In this program, Alm explains, if somebody tests positive for a drug they’re not supposed to be using and they admit it, they get arrested on the spot and typically do two business days in jail. But if they test positive and deny it, they will need to do 15 days. The first time this happens, they are allowed to do their 15 days over five weekends so they can keep their jobs or stay in school. This keeps people connected to the positive things that may incentivize them to stay off drugs.

“The whole idea is not punishment for its own sake,” Alm says. “It is to teach accountability, and that your choices have consequences. And if you think the system is fair, you’re much more likely to buy into it.”

Although a lot of attention on the HOPE program is focused on the swift and certain sanctions, Alm stresses that equally important is the relationship between judges and probationers. Kona resident Ann, who has been in recovery for two years, describes what a typical check-in is like. “The judge calls us to the podium one by one. He talks to us about what we’ve been up to lately, building that relationship with us, commending us if we’re doing well, and seeing how they can help if we are struggling. He asks how long we have been clean and sober, and repeats what we say. Then everybody claps, including the probation officers, attorneys and the prosecutor. And it’s really a good feeling to know that you have all those people there supporting you.”

A 2009 study funded by the National Institute of Justice compared those in the HOPE program to regular probationers and showed that HOPE attendees were 55 percent less likely to be arrested for new crimes, 72 percent less likely to use drugs, and 53 percent less likely to have their probation revoked. Alm is now based in Washington, D.C., where he serves as a legal consultant to the U.S. Department of Justice and Congress, with the goal of implementing more programs around the nation modeled on HOPE.

Ann credits the program for keeping her alive. “Thanks to this, I am where I am at today. I’m clean and sober. I have relationships with my family again and my children. I have my own place. I’m working, I’m doing things I never thought I’d do, because I’d never done them before. In a sense I’m living life for the first time,” she says.

SILVER LINING

Although the state is taking a proactive approach to the opioid crisis, there are still areas that need more resources. Publicly funded recovery centers are in short supply, and it can take weeks for someone struggling to stay in recovery to find an open bed. Ambulance units are also in short supply, especially in remote areas such as where Honda, the EMS captain, works. More people need to be aware of the life-saving potential of naloxone and ask for it in their communities. And to stay ahead of traffickers, the state needs to do more to attract DEA and FBI agents to relocate to Honolulu.

The national attention on opioids has, nonetheless, produced a silver lining: renewed attention on other forms of addiction that are even more deadly yet make fewer headlines. Alcohol is responsible for over 88,000 deaths in the U.S. every year, while cigarettes, including secondhand smoke, kill 480,000. In Hawaii, crystal methamphetamine continues to devastate rural communities.

“Let’s use this opioid plan as a way to identify gaps in our system and address the overall issue of drug addiction and dependence in Hawaii,” says Hawaii Health and Harm Reduction Center Executive Director Lusk. “We’re taking an emergency, finding that silver lining, and using this to leverage our resources so we can be more responsive to any substance abuse issue.”

Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division chief Mersereau agrees that Hawaii can learn from what other states have experienced and get ahead of the opioid problem with a holistic, integrated approach that can be applied more broadly. With the governor’s opioid initiative and the commitment from multiple groups to work together, Mersereau is cautiously optimistic.

“What I find extremely encouraging is the fact that different components are recognizing the need and taking action. Even on the state government side, which tends to be slower because of regulations and rules, the push to be more efficient and effective is there.”

He adds, “Instead of an opioid crisis, I like to think of this as an opioid opportunity.”