Natural Environment: Saving an Essential Part of Hawaiʻi

Here are five stories on how we can prepare for the present and the future, and what individuals, businesses, nonprofits and governments are doing to protect our natural environment.

Part 3: Oceans of Debris

By Jeff Hawe

Hawaii is the canary in the coal mine and this canary is choking on the Pacific Ocean’s plastic and other toxic marine debris.

Beach cleanup crews have removed 767 tons of the debris from beaches around the main Hawaiian Islands over the past 10 years and NOAA has removed another 1,017 tons from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Unfortunately, that’s nowhere near all of it.

Based on dozens of ocean research expeditions, the 5 Gyres Institute estimated in 2014 there were over 5 trillion pieces of plastic in the world’s oceans, weighing over 250,000 tons. The New Plastics Economy report from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation forecasts that the weight of plastic alone will surpass the weight of all the ocean fish by 2050, if we continue on the current path.

Causes: From Land and Sea

“Hawaii is the hot spot of the plastic pollution in the ocean issue, at least within the nation if not within the world,” says Jennifer Lynch, program coordinator for the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s marine environment branch on Oahu.

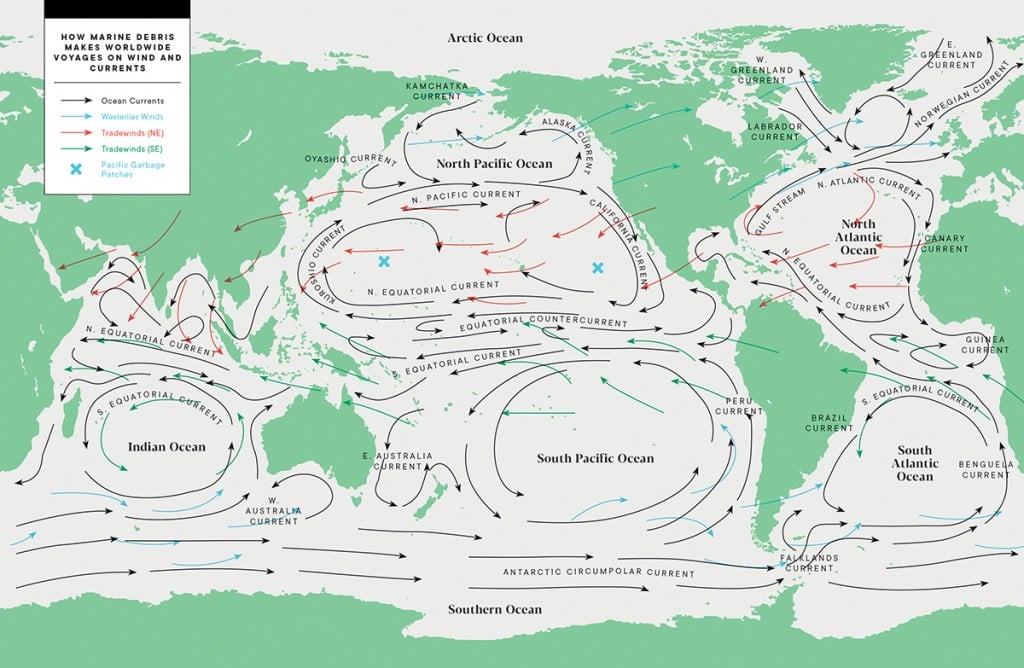

Her research on debris along Hawaii shorelines indicates that leeward coasts typically gather litter from local sources, whereas windward coasts gather trash that has drifted from far away. “Sea surface debris match what’s being found on windward beaches and it’s likely coming mostly from the North Pacific Gyre,” Lynch says.

The North Pacific is home to one of five major ocean gyres. It’s a large circular ocean current cycling clockwise that covers most of the northern Pacific Ocean. This spinning motion gathers debris and creates high-density areas of trash. Trade winds blow surface debris toward Hawaii and its islands act as a giant net that catches it.

Debris typically enters the sea either from the land – when washed downstream or blown out to sea – or by boat crews carelessly or intentionally dumping it overboard.

Poor waste management in developing countries is often blamed for the pollution that originates on land, but Kahi Pacarro, CEO of Parley for the Oceans Hawaii and a founder of Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii, believes they’re just a convenient scapegoat.

He says the underlying cause is a lifestyle of convenient consumption habits, single-use items and packaging that began in the West and has spread to developing countries.

As bad as that is, what’s worse is how much garbage is thrown directly into the ocean. “The vast majority of trash we are collecting on the beaches is coming from the commercial fishing industry fleets that are hunting tuna, and secondarily it’s coming from Southeast Asia.” Fishermen just throw damaged nets, tangled gear and trash overboard, Pacarro says.

The International Marine Debris Conference of 2011 developed a document known as The Honolulu Strategy. It outlines the many sources, threats and impacts of the problem, which have not changed much in eight years. It cites a lack of capacity for waste storage aboard fishing vessels and limited options for disposal in ports, which leads to dumping at sea. That’s illegal under international maritime laws but enforcement is difficult.

Derelict fishing gear and massive tangles of nets, ropes and buoys will snag on and destroy reefs, entangle and kill wildlife, and can carry invasive species long distances. Clumps can easily wrap around a propeller and disable a boat.

Kevin O’Brien is a scientist with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environment Lab and works in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands regularly. He says less than one-tenth of the derelict fishing gear that NOAA finds there comes from Hawaii-based fisheries.

Macro, Micro, Surface and Submerged

Sunlight, waves and wind degrade marine debris. The effects are more pronounced on the lightweight plastics like containers, bags and bottles. As these items degrade, they break into smaller and smaller pieces. According to 5 Gyres Institute research, they eventually become like a smog of plastic particles dispersed throughout the ocean, from the surface to the seafloor.

Marine animals mistake these plastics for food and eat them. We know this because scientists are finding plastic in the digestive tracts of dead animals. What we don’t know is the full scope of the consequences. Lynch’s research on turtles so far has found the effects on adult turtles are often negligible but for hatchlings and juveniles, which tend to eat a lot of plastics, it creates problems that often result in death. She says “the jury is still out” on the full impacts.

David Hyrenbach, an associate professor of oceanography at Hawaii Pacific University, has conducted and published several studies on plastic ingestion. His latest study, yet to be published, found plastic in the digestive tracts of 86 percent of albacore tuna sampled and 40 percent of skipjack. Research is ongoing as to what this means for humans who consume fish.

O’Brien says we need to weigh the possibility of plastic getting into the food chain and affecting our food supply. “We don’t have great data on that yet, whether plastic chemicals are making their way into the tissues of fish via ingestion or whether they pick it up from the ocean water which has these chemicals present. We just don’t know.” Research is ongoing he says.

What’s worse is that marine debris, primarily plastic, can absorb and concentrate pollutants from ocean water. The Honolulu Strategy document points to plastic fragments collected from the Pacific that tested positive for toxins like PCBs and DDT.

PCBs and DDT accumulation in humans is associated with cancer, birth defects, infant death and brain damage. Potentially unsafe levels of these chemicals have been found in marine wildlife, though research has not made a definite link between these levels and consumption of contaminated plastic.

Solution 1: Cleaning it up

Removing marine debris from reefs and beaches isn’t easy or cheap – especially in remote locations like the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, where debris must be brought to Oahu for disposal. Cleanups on the main Hawaiian Islands depend on volunteers, donations and grants. But the indirect costs are much higher: Beaches and nearshore water littered with debris are more likely to keep away both locals and visitors.

Says Pacarro, who has been a longtime advocate of the motto “clean beaches start at home”: “Hawaii stands to lead by example of how a community that has beaches that are paradise and a tourism-centric economy should be. … The way that we change the world is by having people see the way we do things and then emulate it.”

He says that means we can have the greatest effect by making responsible consumption choices and refusing single-use items. Beach cleanups emphasize those lifestyle changes to participants wrapped in the awareness that comes from removing tons of trash off a beach.

Numerous environmental groups organize beach cleanups all over the state; see the box to learn about how to volunteer.

NOAA’s Marine Debris Removal Team at midway atoll. | Photo: Courtesy of NOAA, 2016

Solution 2: Business with a triple bottom line

The consensus among researchers, policymakers, activists and even die-hard beach cleaners is that we are not going to be able to clean our way out of this. The problem must be tackled at the sources – and that will take both public and private steps.

One business focused on ocean health is Outrigger Hotels and Resorts. Its Ozone program partners with the Waikiki Aquarium to educate guests; supports ocean nonprofits like Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii and Kokua Hawaii Foundation; and promotes sustainable practices and products within the hotel chain.

“We aim to be the premier brand of beach resort and if the beaches and ocean around us are not healthy, we are not doing our job right,” says Monica Salter, Outrigger’s VP of corporate communications.

Among the steps taken, Outrigger has placed filtered water stations throughout the hotel to provide an alternative to bottled water. Its two in-house restaurants implemented changes to make them “Ocean Friendly,” a classification awarded by the environmental group Surfrider Foundation to restaurants that don’t use polystyrene containers or plastic bags, that recycle and that offer reusable tableware for dine-in customers and disposable utensils and straws only upon request.

Salter says Outrigger is focused on a complete transition away from plastic beverage bottles and on reducing plastic in general. She says it’s tricky to give guests what they want and still be environmentally friendly. “It’s not necessarily expensive or difficult; it’s more of a mindset shift and you have to get the buy-in of company leadership.” She says CEO and President Jeff Wagoner is committed.

Change is worthwhile but not inexpensive or easy, says Garrett Marrero, owner and founder of Maui Brewing Co., which is known for its eco-friendly approach to brewing and selling beer. He favored the intent of Senate Bill 1527, which aimed to eliminate six-pack rings in Hawaii, but said the legislation was not well-thought-out. “It is cost prohibitive and many breweries in the state would not be able to afford it. … I think the Legislature should bring in industry stakeholders to share knowledge and data in how to best implement it.”

The bill died in this year’s state Legislature.

The six-pack connecters that Maui Brewing uses for its cans of beer – which he says were not likely to be banned by the bill – are solid pieces of plastic made from recycled materials and were chosen after much research.

“You would not believe how many times I have gone to packaging conferences and talked to every producer searching for the most eco-friendly product they have,” Marrero says. He advocates that companies do their research on the most sustainable practices when it comes to all aspects of their businesses, not just packaging.

Ignacio Fleishour owns a restaurant and catering business in Kaimuki called Makana Ranch House that’s on Surfrider Foundation’s ocean-friendly list. “Truly, I think everybody wants to be eco-friendly. I often weigh using compostable materials versus using water to wash dishes and I can’t decide what’s best,” he says.

Makana serves food on compostable plates and utensils when single-use is necessary. “Yes there is a higher cost to offer a nice plate that is compostable, but as people get used to that idea and what it represents they are willing to pay the higher margins if they know that story,” Fleishour says.

Solution 3: Policy to Protect

In 2010 NOAA gathered key marine debris stakeholders from government, nonprofit and ocean-based industries for a dialogue. The Hawaii Marine Debris Action Plan was the result. Its goal is to reduce the impacts of marine debris in Hawaii by 2020 by focusing on prevention and reduction of sources, removal of debris and derelict vessels and research to greater understand the problem.

The plan has since evolved, says Mark Manuel, Pacific Islands marine debris regional coordinator for NOAA: “There’s been a lot of buy in, especially recently. It was initially heavily focused on removal but now it has morphed into a proactive preventative approach to marine debris.”

Manuel points to “a lack of truly understanding the problem, holistically, from a research and data stance.” But what’s clear, he says, is that Hawaii is a hot spot and that “we need to think globally, Pacific-wide, and act locally.”

Manuel says the plan has been successful so far, with hundreds of thousands of pounds of debris removed from beaches, reducing risks to monk seals and turtles. The plan has also received support from the state and counties, which he says is a big accomplishment, and has aided in the establishment of research priorities. But above all, Manuel says, it has helped numerous organizations coordinate their actions to reduce redundancy and improve effectiveness.

State Rep. Chris Lee introduced a bill in 2018 and again in 2019 that sought to establish a Plastic Pollution Initiative Program. At press time, a similar bill (SB 522) was still alive at the state Legislature. Unlike many of the ban bills that focus on particular items like plastic straws and bags, the bill seeks to establish a long-term plan for eliminating plastic pollution in Hawaii’s environment. It proposes establishing an advisory council to collect data, identify next steps and provide recommendations.

“We’ve tackled plastic bags, straws, foam individually, but ultimately I think it’s important we look at the thing as a whole and not get lost in the weeds. … Any one solution may be great for that one particular slice of the puzzle, but we want to do something that’s comprehensive and makes sense,” Lee says.

“There is a lot of inertia and resistance to change.”

He believes careful implementation of policy and innovative solutions can create economic opportunities for new businesses and products that manage and reduce our waste. “Successful companies are those that adapt and change to better … both themselves and the community. When you actively resist that, even when people are reaching out to help, then the risk is all on you,” Lee says.

Every Person Can Help

Here is what you can do:

Clean a beach: The best way to learn about the problems washing up on our shores is through hands-on experience, and with over 11 organizations statewide holding beach cleanups regularly, there are plenty of opportunities to volunteer. Visit any of these organizations’ websites to learn more: 808cleanups.org, sustainablecoastlineshawaii.org, wildhawaii.org, oahu.surfrider.org, kauai.surfrider.org.

Practice the five R’s: This is an expansion of the three R’s waste management mantra. It begins with redesigning products and services to produce less waste. Next, refuse items that will generate unnecessary rubbish: Don’t buy them, don’t share them. Then reduce, reuse/repair and recycle. The hierarchy places emphasis on the most effective steps first.

Be civically engaged: Voice support and testify on the bills, proposals and policies you think address the problem appropriately. There are lawmakers and activists working for change, and there are opponents. Lend your voice to the conversation.

Spend wisely: The dollar is powerful and where and how you choose to spend it lets companies know what you want from them, their products and their services. Buy with the ocean in mind and companies will take note.

Learn more: 5gyres.org has a resources section that is full of information on plastic pollution.

Choose sustainably sourced seafood: This can be tricky. A good rule of thumb is buy fish caught by local fisheries; Hawaii fisheries usually comply with fishery laws. Fresh poke is generally locally caught; previously frozen poke is usually not, Pacarro says. If you’re unsure, ask the person behind the counter about the country of origin or how it was caught. Learn more at hawaii-seafood.org.

Quicklinks

Part 1: Resilience

Part 2: Six Ways to Deal with Our Disappearing Beaches

Part 3: Oceans of Debris

Part 4: How to Make Your Company Green

Part 5: Zero Waste

Ongoing Efforts and Other Resources