Natural Environment: Saving an Essential Part of Hawaiʻi

Here are five stories on how we can prepare for the present and the future, and what individuals, businesses, nonprofits and governments are doing to protect our natural environment.

Part 1: Resilience

What does it mean to create a resilient Hawaii and how do we get there?

By LiAnne Yu

We are vulnerable. It can be easy to forget that while we go about our daily lives, filling up our gas tanks, working in our air-conditioned offices, picking up groceries on the way home, doing the laundry and making dinner.

Yet we do all of this while living nearly 2,400 miles away from the nearest landmass, making us among the most geographically isolated human populations in the world and one that is extraordinarily dependent on goods and resources shipped across the ocean to us. Ninety percent of everything we eat arrives every four days in 400 containers. We pay $5 billion a year for the petroleum that fuels our cars and lets us turn on the lights. What happens when such access is compromised?

Our vulnerability is exacerbated by the accelerating effects of climate change, which we have witnessed in the form of a 100-year storm, record-breaking king tides, beach erosion and dying coral reefs. What happens if a Category 5 hurricane hits Honolulu?

“Folks don’t realize the fragility of Hawaii, the fragility of our economy and infrastructure. We don’t fully appreciate the fact that so much of what we have here, such as being able to keep the lights on and goods flowing into the state, is vulnerable,” says Blue Planet Foundation’s executive director, Jeff Mikulina

How do we address those threats that may not always be visible day to day, yet have the capacity to impact our work, families, homes, health and security?

A collapsed house downstream near the Hanalei Pier during the 2018 flooding on Kauai. | Photo: Courtesy of NOAA/National Weather Service

In recent years, the term “resilience” has been used to describe what we want our communities and cities to embody in the face of accelerating climate change, environmental degradation, economic stress and social fracturing. Honolulu was named one of the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities, and in 2016, the City and County of Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency was established.

“Resilience is the ability to survive, adapt and thrive no matter what shocks or stressors come our way. It’s about being flexible. It’s about being able to pivot and bounce back from anything,” says Josh Stanbro, executive director of the office.

Shocks include sudden events such as 2018’s record-breaking storm on the north shore of Kauai. Stressors include chronic issues, such as beach erosion in West Maui and the high price of housing. Shocks and stressors often work in wicked tandem. “When there’s a big storm and the roads are blocked, it can exacerbate poverty if people can’t get to work,” says Aki Marceau, managing director of the Elemental Excelerator

But resilience is also more than just keeping our heads above water, so to speak. “We don’t want to just survive during these shocks or stressors. We really want to have a thriving community. Survival feels like you’re just living paycheck to paycheck. You’re making ends meet. Whereas when we’re thriving, we have a very strong sense of community well-being and the ability to bounce back,” says Marceau.

In this piece, Hawaii’s community and policy leaders weigh in on what a resilience strategy should focus on, in light of both our vulnerabilities and our strengths as an island state.

Grit

“When you think about kids on the school ground and who succeeds through adversity, it’s not always the smartest kid or somebody who comes from the best family. It’s those kids that don’t ever give up. They’re like, ‘Look I’ve got to make the grade, I’m going to figure out how to work harder,’ or, ‘I didn’t make the team, I’m going to go practice. It’s the ability to pick yourself back up, innovate, and stick to it.

“In many ways, resilience is grit,” says Stanbro.

Hawaii is, in some ways, like that kid who’s always the smallest and most vulnerable in class. We are isolated, we are extremely dependent on goods and resources that come from elsewhere, we are extremely dependent on the fickle industry of tourism, and we have some of the highest costs of living in the country.

But, as Stanbro suggests, Hawaii is also that kid who just works harder than everyone else. Although Honolulu was nearly the last city among the 100 Resilient Cities network to begin developing a resilience strategy, it is among the first half to have completed a plan.

“That speaks to the mayor’s commitment to not mess around and hurry up. We’ve been in a full-court press for just over a year to go out, talk to the community, figure this out, and get it out quick. We’re not like other cities that lingered for two, three years putting together their strategy. We’ve jumped from the back of the pack, up to the front,” says Stanbro.

That resilience strategy for the island of Oahu details 44 proposed actions to protect our people, economy, infrastructure and resources. Developed in collaboration with community, nonprofit and business leaders, these points are, Stanbro says, deliberately focused on concrete policies and programs.

To address shocks caused by natural disasters, for example, are calls to update building codes, retrofit homes and implement a long-term recovery plan. To address climate change, there are calls for energy-efficiency ordinances, seawater air conditioning and electrical vehicle charging infrastructure.

While some may question the costs, Stanbro points out that these investments ultimately save us money. “There’s new FEMA data that says for every dollar you spend on building code updates, there will be $11 of savings on the back end after a disaster strikes.”

Figuring out how specifically we are going to pay for both disasters and chronic environmental problems also requires grit, as the numbers add up rapidly. The Hawaii Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Report estimates the lost value of flooded structures and land at over $19 billion. But that doesn’t include the impact to our visitor economy, natural resources or infrastructure. Some think the magnitude of loss will be closer to $190 billion.

Hurricane Iniki hit Kauai in 1992, resulting in six deaths, over 6,000 destroyed or severely damaged homes, and a population exodus that still impacts the island’s economy and workforce decades later. As devastating as that was, the $3.1 billion price tag is only a tenth of the estimated cost of a similar hurricane hitting Honolulu, says Alex Kaplan, senior VP at Swiss Re, one of the world’s leading providers of reinsurance.

Not having a plan will leave us with only bad options later. “There’s three ways that governments fund these disasters. One, they raise taxes. Two, they raid budgets, so instead of building that new state-of-the art-hospital in Manoa, they’re having to go fix the Ala Wai Canal. And three, they issue debt post-event, in an unfriendly and unattractive capital market,” says Kaplan.

Assuming someone else will take care of us is also not the answer, he continues. “If the expectation is that somebody else is going to bail us out, it will lead to inaction and indifference. But when we recognize that the risk has to be borne where the risk is present, then we can make better decisions.”

Self-Reliance

Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in 2017. Over 3,000 people died, and the total loss of $91 billion makes it among the costliest hurricanes in history. But the hurricane was only the start of the suffering, as the already fragile electrical grid was destroyed, leaving the sick, elderly and isolated without central power for 11 months.

That should serve as a warning to us about how much we take our power sources for granted, says Blue Planet Foundation’s Mikulina.

“It turned into ‘Lord of the Flies’ pretty quickly over there, and they are way more accessible from the Mainland than we are. How can we ensure that our home here is protected against that?”

Lessening our dependence on one central grid is a start, Mikulina says. Microgrids break up an area into distinct sections that can power themselves should something happen to the other parts. Camp Smith has one, and efforts are being made to bring the technology into broader commercial use.

Clean energy sources, such as the sun, can also be managed at a house-to-house level, lessening the possibility of a whole town losing power. “A solar water heater is going to work whether or not the grid is up and running. A hot shower is just a nice luxury to have after something terrible happens. But it underscores that the more we can make it local and clean, the stronger we’ll be as homes, as communities, and as an island,” says Mikulina.

The dropping costs of solar energy and storage are also reaching a point where most can afford to have their own, localized energy source. “Some of those projects are as low as 8 cents per kilowatt hour for solar that’s stored, which is amazing because it demolishes two myths people have about renewable energy. One, that it’s expensive and two, that it only works when the sun is out. But now you can get solar at night for almost half the price of fossil energy. It’s not just a little cheaper. It’s hands down a winner,” says Mikulina.

Our dependence on imported food is another source of vulnerability. If an environmental or geopolitical event disrupted those daily shipments, we would only have enough to eat for at most 10 days.

In response, Hawaii’s local food movement continues to grow. To support that, Gov. David Ige has set a goal of doubling food production by 2020, investors like Ulupono Initiative are focusing on food production operations, schools are introducing students to community gardens and companies like Kunoa Cattle are making a bet that people in Hawaii do care about where their meat comes from.

“We often say to people at the end of our presentations, ‘OK we just laid out a lot of things that are super scary in terms of climate change. What are the things that you can do when you go home tonight?’ And one of them is just buying local agriculture. Either growing food in your backyard or signing up for a community supported ag box. You’re eating better and you’re lowering your carbon footprint,” says Stanbro.

“But you’re also making us more resilient because if we get hit and the ships can’t come, we need local farms to have the capacity to feed us. And that only happens if we support them now while we still have blue skies.”

Stewardship

Because we are witnessing the acceleration of sea level rise and its effects on our coastal communities, conversations about resilience tend to be tilted toward how to ensure the longevity of our human-made things, such as homes, highways and water pipes. Nonetheless, if we are going to overcome our vulnerabilities, we must also focus on the longevity of our natural resources.

Proper stewardship is not just the right thing to do from a moral or philosophical standpoint. It can have tangible impacts on our own well-being, says Ulalia Woodside, executive director of the Nature Conservancy of Hawaii.

She describes what happened at Waikamoi Preserve, which covers 9,000 acres in the East Maui watershed. Feral pigs were digging up the lichens and mosses that covered the forest floor. This undergrowth serves an integral role in the watershed ecosystem as a sponge soaking up precipitation captured by trees, allowing the water to gradually make its way into underground aquifers. By fencing off this area, Woodside says the Nature Conservancy helped preserve $36 million worth of water for Maui’s households, businesses and farms. But the healthy undergrowth also serves another purpose: It holds the soil down so that it doesn’t wash away into the ocean during a storm, killing the coral reefs that we need to protect our coasts from wave energy.

Ulalia Woodside is the executive director of the Nature Conservancy of Hawaii. | Photo: Elyse Butler

“We need to remember that our human world depends on the natural world, and as we plan for ourselves and the human world, there are natural infrastructure and natural systems that also need our attention,” says Woodside.

Taking care of our natural resources is not something we can put off, says Department of Land and Natural Resources Chairperson Suzanne Case. If we don’t rehabilitate them, she says, they won’t serve us when we need them the most – after a disaster.

“A native forest is likely to withstand high winds and rains better than a forest of non-native, invasive trees, which are brittle. If the coral is already under stress from sediment and erosion, invasive algae is more likely to take over after a bleaching event, smothering them before they have a chance to grow back. If fish aren’t well-protected and managed, they won’t survive into their adult stage and won’t reproduce successfully,” says Case.

“Just think of it as if you’re sick and you’ve been running yourself thin from working too hard or playing too hard or traveling too much. You’re much more likely to get sicker from a disease than if you’re rested and in good condition and can combat the disease. Our planet is the same way.”

Rootedness

While the concept of resilience has gained currency in recent years and there are global efforts, like 100 Resilient Cities, to support and share best practices, Rosie Alegado reminds us that we don’t have to look beyond our shores for successful models. Practices of resilience have always been deeply rooted in the worldview of island inhabitants.

“When we discuss resilience, we often come at it from a continental point of view. When you live on a continent, you have the ability to move when you run out of resources. When you’re on an island, you just can’t do that. So it’s important to remember that the islanders who have inhabited the Pacific for thousands of years were really good at being resilient. And why were they really good at it? Because they were good at living at the very end, the very boundary conditions of existence. It was survival plus,” says Alegado, assistant professor in the UH Manoa Department of Oceanography and UH Sea Grant Program.

Illustration: Bryson Luke

Accounts of a settlement called Kahikinui illustrate how scarcity shaped everyday practices. “That area was very dry, a kind of no man’s land between Kaupo, up Kipahulu and Upcountry Maui. Very underdeveloped. We know that historically, Hawaiians lived there. And we know that they had all kinds of mechanisms and processes for catching water, maintaining water and through very thrifty conservation of water, surviving,” says Alegado.

“Let’s investigate and identify this historical legacy,” she continues. “How did the people of the Pacific survive these really harsh conditions? And how can we reflect that in our practices today?”

For the Nature Conservancy’s Woodside, the heart of Native Hawaiian knowledge was a detailed awareness of change borne through detailed observations.

“People engaging in voyaging traditions, hula traditions, farming traditions and fishing traditions were all acutely aware of the moon calendar, acutely aware of the sun’s cycles, acutely aware of the seasons. What are the tides doing throughout these seasons and times? Which months are the wet months? If you were a farmer, you had detailed observations about the clouds, the forests, the water cycles and your stream,” says Woodside.

Such knowledge was then passed down. Describing Kaupulehu fishermen, she says: “Generations passed down accounts of the size and number of opihi that they had caught over time. They started to recognize that their catch was not the same as their grandfathers’ generation. In passing that knowledge down, they’ve been able to say, ‘Hey, something’s off in the system. This isn’t the level of abundance that we’re used to.’ They were then able to figure out what kind of changes needed to be made.”

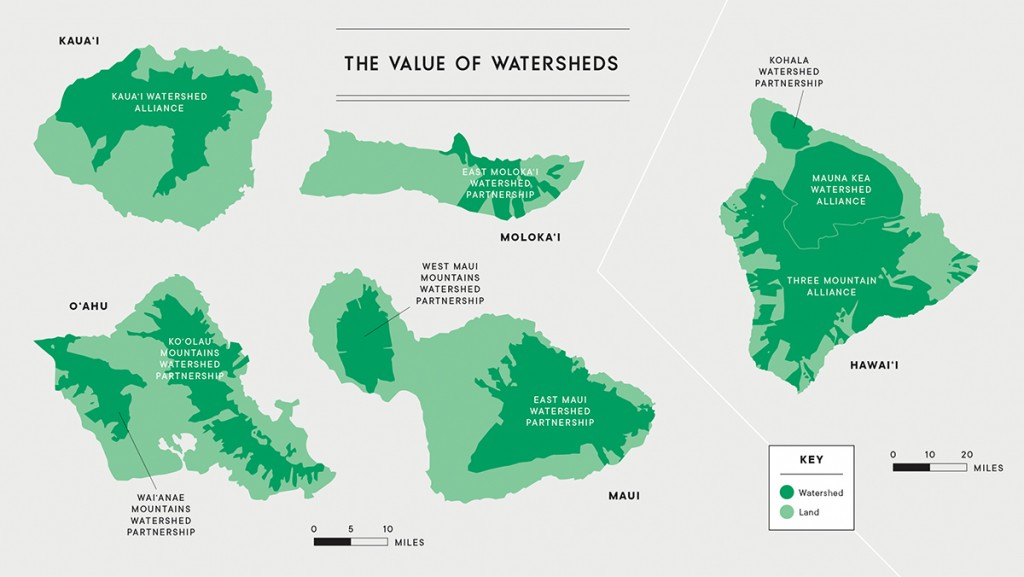

Eleven partnerships protect more than 2 million acres of watershed forests and land in Hawaii. Watershed areas and native forests allow native plants and animals to thrive and help capture rainwater. And they make Hawaii more resilient to climate change by reducing drought, landslides, flooding and runoff. | Source: State Department of Land and Natural Resources. Also see: Hawaii Association of Watershed Partnerships

Accountability

For Rafael Bergstrom, beach cleanups are about more than just picking up trash. They are a way for people to understand the connection between their everyday choices and the impact of such actions on the environment.

“It does feel good when you go and clean up a beach, and you feel like you’ve made a difference. But the true work is still so far beyond that. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on something, rather than actually going to the source of the problem,” says the executive director of Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii.

Although people understand that plastic pollutes the beach and harms marine life, Bergstrom says, they are not always aware that single-use bottles, bags and food packaging – the very things we bring to our beach picnics – are made from fossil fuels. And not only does the production of plastic contribute to climate change, but as plastic breaks down, it also gives off additional greenhouse gases.

“We use beach cleanup as an entry way into having broader conversations about our heavily consumer driven and convenience-based culture. We’re using things once, for no more than five to 10 minutes, then throwing them away and not really understanding the repercussions,” says Bergstrom.

In a similar way, Camilo Mora wants to provide people a way to take personal ownership over their own contributions to climate change. The key, he says, is in becoming carbon neutral. The premise of his project is for individuals to calculate how much CO2 they generate, estimate the number of trees necessary to sequester those emissions, and then go out and actually plant those trees.

“If each person in Hawaii plants 100 trees, or just 10 trees a year over 10 years, we will have enough trees to sequester 800 million tons of carbon. That’s 40 years’ worth of carbon,” says Mora, associate professor in UH Manoa’s Department of Geography and Environment.

Mora acknowledges the challenges: high tree mortality due to lack of water and weeds, issues of where to plant the trees, and finding space to propagate the seeds.

Nonetheless, he believes that these are surmountable challenges if there is public and political will. “I look at the huge buildings in Honolulu and I think, if they can build that in a year, why can’t we get behind a project to plant these trees and make it a yearly event.

“Would you commit 10 hours of your time to plant 10 trees a year, knowing that we could be carbon free for decades to come? Rather than passing the responsibilities to people down the road, why don’t we do it now?”

Bouncing Forward

If we had all known then what we know now, would we have done anything differently? Would we have built Waikiki or Lanikai or West Maui the same way, knowing how sea level rise would threaten development close to the coasts?

To make sure such questions are consistently considered, the Hawaii Sea Grant College Program is releasing a set of reports on the post-disaster planning process and establishing development guidelines informed by the Hawaii Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Report. Funded by a NOAA grant, these reports were created in partnership with the DLNR, the state Office of Planning and Tetra Tech.

“Resilience is not just putting our communities back exactly the way they were before,” says Bradley Romine, UH Sea Grant Program coastal processes specialist. “We’ve made mistakes, frankly, in terms of how we’ve developed our shoreline communities. So how can we seize these opportunities when disasters happen, to build back smarter?”

Kitty Courtney is a marine environmental scientist with Tetra Tech, a California-based consulting and engineering services company that focuses on sustainability. She explains that after an emergency, managers respond to the immediate dangers brought on by the event. But there is no consistent process for how county planners should manage the next steps around permitting and rebuilding.

“Certain levels of damage require a pause, so that we can evaluate whether something should be built back. But these are things that need to be done ahead of time, not when people are hurting from a disaster. So what kinds of conversations can we have with our communities now, so that we’ve all thought through the dilemmas that will be encountered? Then we can do a better job of helping people move to safer areas, and ultimately build community resilience into the process,” says Courtney.

The changes required to rebuild in a more resilient manner will not always be met with universal enthusiasm, Stanbro acknowledges. The Ala Wai Flood Risk Mitigation Project, which would protect Honolulu and Waikiki from stormwater, has some concerned in terms of its potential impact on their views and their properties.

It is critical to listen to such concerns, says Stanbro. At the same time, he says, we need to consider that a major catastrophe hitting the center of our urban and visitor economy is not a matter of if, but when.

“What are we going to do to protect those things we love most about Hawaii? How will we be willing to change?”

He points to Hilo as an example of both what can happen when a community is not willing to change, and what can happen when it is. In 1946, a tsunami tore apart and flooded the downtown area with waves as high as 50 feet. One bay front community was entirely washed away, and then rebuilt in exactly the same place, and then destroyed a second time when another tsunami hit 14 years later.

“After the second time, they said, we can’t reinvest again just for it all to be swept away. So they got together as a community and reshaped the town, relocating to an area that was on higher ground. When Hurricane Lane pummeled Hilo last year, the soccer fields and gas station flooded. But that’s it. The rest of town was fine,” says Stanbro.

Hilo offers lessons on how shocks and stressors must be integrated into our long-term planning. It also demonstrates that resilience is not an end state that we can get to and then be finished. Rather, it is an ongoing endeavor to always be a step ahead of everything we can anticipate and imagine. “Resilience is not just about bouncing back pretty quickly. It’s about bouncing forward,” says Stanbro.

“It’s about incorporating lessons learned, positioning yourself differently so that you’re in a better, stronger position the next time another event happens. Resilience is not one step forward, two steps back. It’s one step back, two steps forward.”

Quicklinks

Part 1: Resilience

Part 2: Six Ways to Deal with Our Disappearing Beaches

Part 3: Oceans of Debris

Part 4: How to Make Your Company Green

Part 5: Zero Waste

Ongoing Efforts and Other Resources