CHANGE Report on Arts and Culture and the Revival of the Hawaiian Language

Part 2: “We’ve Really Moved the Needle”

Education in the Hawaiian language has surged for four decades and its advocates eventually want a Hawai‘i where the native tongue is used as frequently as English

“Imagine a world where wherever you go, you hear ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i,” says Ryan Gonzalez of Kamehameha Schools.

Last June, he and about 5,700 others visited a world just like that during the Hawaiian language night at the 50th State Fair. Attendees asked for tickets, ordered food and played games in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i.

“Everybody talks about living language and vibrancy and I’m not sure if most people have a clear idea of what that exactly means, but to see it in action, it’s ‘OK, this is totally what people are talking about,’ ” says the director of network engagement in Kamehameha Schools’ Kealaiwikuamo‘o division, which supports the Kanaeokana network of Hawaiian immersion schools, culture-based charter schools, the UH community, DOE programs and community-based nonprofits. One of Kanaeokana’s goals is to renormalize ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i throughout society.

Hawaiian Language Teachers Larry Kimura, left, and William “Pila” Wilson | Photo: Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu

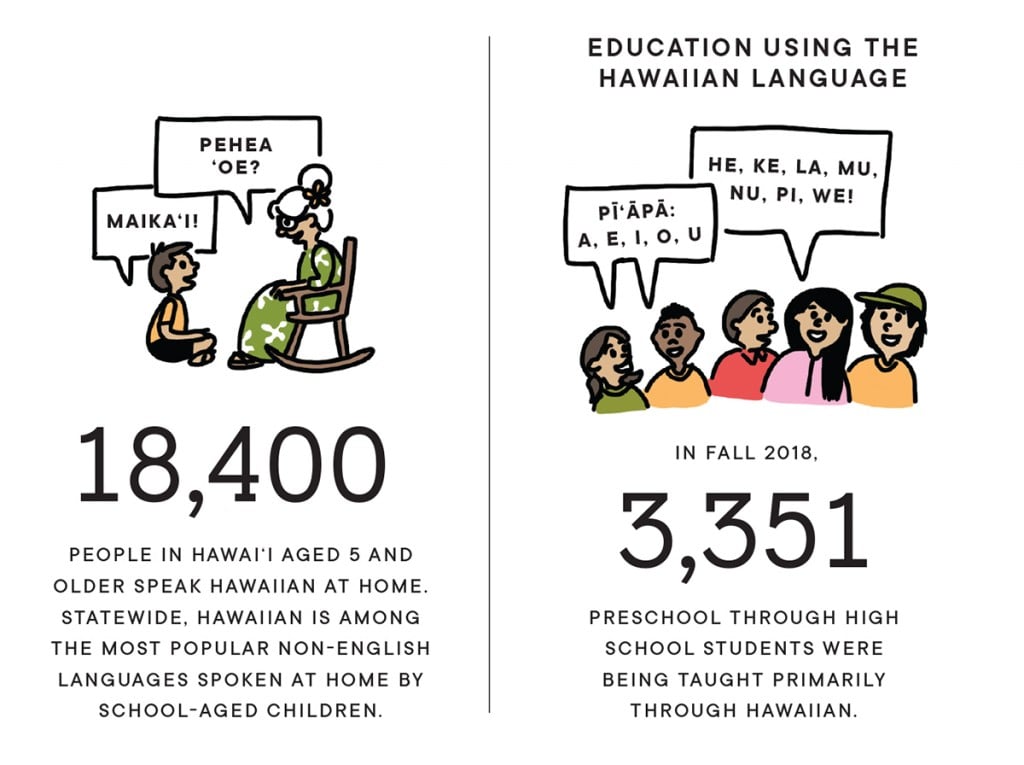

Several people interviewed for this story agree the language has come a long way since its near extinction. ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i has been an official state language since 1978 and since then, Hawaiian language schools and UH Hawaiian language programs have developed new generations of ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i speakers. According to an April 2016 report by the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism, 18,400 people aged 5 and older spoke Hawaiian at home in Hawai‘i. Today, that number is likely higher, and Hawaiian can be spoken, heard, written and read in a variety of sectors, from education to media to science to tourism.

However, the language still has a way to go to be renormalized. Despite it being one of two official state languages, it is obvious that Hawaiian is not on an equal footing with English in the everyday world. Because English is the dominant language, many people don’t see a need or value in having Hawaiian language in government and business, and even Hawaiian language speakers might default to English in certain situations. And while there’s lots of interest in more keiki learning and speaking Hawaiian, local immersion schools face challenges keeping up with increased demand.

“Some people have this kind of wild idea that Hawaiian language is all over the place, … but it still has a far, far way to go,” says Larry Kimura, an associate professor of Hawaiian language and Hawaiian studies at UH Hilo.

Living Language

It only takes one generation to lose a language, Kimura says, and after ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i was banned in schools in 1896, the language almost died. In the early 1980s, an informal count estimated that fewer than 50 keiki under 18 could fluently speak Hawaiian. Because schools didn’t use Hawaiian, the language almost completely disappeared in homes, says William “Pila” Wilson, who helped conduct the survey and is now a professor of Hawaiian studies and linguistics at UH Hilo. The exception was on Ni‘ihau and in families like his that raised their children in Hawaiian.

Wilson and Kimura were part of a group of Hawaiian language teachers that started ‘Aha Pūnana Leo, a preschool that teaches students entirely through Hawaiian, and pushed for the reestablishment of Hawaiian as a legal language of instruction. The first site opened on Kaua‘i in 1984; today, there are 12 sites statewide. That program is supplemented by Ka Papahana Kaiapuni, the state Department of Education’s K-12 Hawaiian Language Immersion Program that was established in 1987. Students in the program are taught through Hawaiian, and English is introduced in fifth grade. UH offers bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degrees, plus a post-baccalaureate teaching certificate, with courses taught primarily in Hawaiian.

Wilson, a member of Pūnana Leo’s board of directors, says 3,351 pre-k-12 students were taught primarily in Hawaiian language during fall 2018. Statewide, Hawaiian is among the most popular non-English languages spoken at home for children ages 5-17. That’s a sign that the status of Hawaiian is rising, Wilson says, adding he’s seeing more children enrolling in Pūnana Leo already having a background in the language.

In the past, parents would worry that sending their children to immersion schools would hinder their ability to function in an English-speaking society and higher education, Wilson says. However, that’s not the case, he says. He cites the Hawaiian language college’s laboratory school, Ke Kula ‘O Nāwahīokalani‘ōpu‘u Iki Lab Public Charter School, where he also teaches. More than 95% of the student body is Native Hawaiian, and more than 60% qualify for free and reduced lunch. All students graduate and between 83% and 87% go on to college right after high school. The overall public school on-time graduation rate for the class of 2018 is 84%; the college enrollment rate is 55%, according to Hawai‘i P-20 Partnerships for Education.

Ekela Kaniaupio-Crozier has taught Hawaiian language for over 30 years at UH, Saint Louis School and Kamehameha Schools. Today she’s a Hawaiian culture-based education learning designer and facilitator at Kamehameha Schools Maui. She says: “We’ve really moved the needle. I’d say that. We have so many children who can speak, we have adults who can speak, we hear language being, the soundscape is different.”

Back in the day, she knew everyone who could speak Hawaiian. “Pretty much our village was small,” she says. “And today I can go to places and have no clue who that person is and they’re speaking beautiful Hawaiian, and that’s cool. For me, this is a great indication of how far we’ve come with our language. … It’s no longer a village, it’s a community … a very large community of people who speak it for whatever reason.”

Growing More Speakers

Interest in learning Hawaiian is on the rise, says Kalehua Krug, an educational specialist with the DOE’s Office of Hawaiian Education. Ka Papahana Kaiapuni, the DOE’s Hawaiian Language Immersion Program, has grown tremendously since its establishment in 1987 with pilots at two elementary schools: Waiau in Pearl City and Keaukaha in Hilo.

Back then, only 34 students were enrolled, Krug says. This past school year, there were 3,200 students enrolled in programs at 17 DOE and six public charter schools, and more schools are expected to open or expand their kaiapuni programs in the coming years.

The challenge is keeping up with this demand, Krug says, which is growing faster than the DOE capacity to provide human and community resources. The language is still endangered, he adds. “The level of proficiency needed to keep a language alive, the number of speakers necessary in the community to ensure that there’s always high level access for people who want to learn, I think that’s our struggle right now internally … trying to figure out how do we grow children in the kaiapuni program so the proficiency is somewhat nativelike and be that future resource for survivability and perpetuity of Hawaiian language.”

Most kaiapuni schools face a severe shortage of licensed, proficient kumu, writes Keli‘ikanoe Mahi, po‘okumu (principal) of Ke Kula ‘o ‘Ehunuikaimalino, a K-12 kaiapuni school in Kealakekua, in an email. C. Babā Yim, po‘okumu of Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Ānuenue, a K-12 school in Kaimukī, writes that the challenge is finding people who are trained as teachers and also proficient in the Hawaiian language. Most are one or the other, but rarely both, he writes, adding that middle and high school positions are especially tough to fill because they require specific content knowledge along with the necessary language associated with that content area.

Students from Ke Kula ‘o ‘Ehunuikaimalino, a school in Kealakekua on Hawai‘i Island. Students are taught entirely in Hawaiian until the seventh grade and mostly in Hawaiian from eighth grade on. | Photo: Courtesy of Ke Kula ‘o Ehunuikaimalino

Olani Lilly, po‘okumu of Ka ‘Umeke Kā‘eo, a pre-K-10 kaiapuni charter school on Hawai‘i Island, faces challenges with finding teachers who can teach subjects like calculus and science while integrating Hawaiian language at the secondary level: “Finding that teacher is like a unicorn,” she says with a laugh.

The DOE’s Office of Hawaiian Education estimates there are about 200 kaiapuni teachers, and at the beginning of the 2018-19 school year there were about 40 vacancies. For the upcoming year, the office estimates there will be more than 45 vacancies.

Mahi says too few people want to become teachers, both among those proficient in Hawaiian and those who speak only English. Krug, who has been with the Office of Hawaiian Education for four years, says growing kaiapuni teachers was something UH’s College of Education struggled with when he worked there. Another challenge is that kaiapuni teachers have heavier workloads because they have to learn another language and often create their own curriculum – for the same pay as someone teaching in English.

Wilson of UH Hilo says it’s hard to get people up to the level of proficiency needed to be a Hawaiian language teacher – it takes about 1,100 hours of Hawaiian language experience. The college’s Kahuawaiola Indigenous Teacher Education Program is the only teacher education program that prepares kaiapuni teachers using Hawaiian language. Wilson says teacher candidates who complete this program and possess a B.A. in Hawaiian have about 1,300 credit hours of Hawaiian language classroom use and instruction under their belts. Delivering the post-baccalaureate program primarily in Hawaiian helps teacher candidates develop a proficiency and the vocabulary necessary for the teaching field, adds Keiki Kawai‘ae‘a, director of UH Hilo’s Ka Haka ‘Ula O Ke‘elikōlani College of Hawaiian Language.

HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE SPEAKERS

Read the 2016 DBEDT Report

Sources: State Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism; William “Pila” Wilson, UH Hilo

Some kaiapuni schools are addressing the teacher shortage by developing online courses in Hawaiian. During the 2018 fall semester, 11th graders at the Ke Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Ānuenue and Ke Kula ‘o ‘Ehunuikaimalino piloted a Hawaiian language Modern History of Hawai‘i online course. Students at ‘Ehunuikaimalino took the course during the school day and were taught by an ‘Ānuenue teacher.

Mahi writes that the idea is to grow this concept so that more classes taught by licensed Hawaiian proficient teachers can be accessed by kaiapuni students. “The kaiapuni student population is growing faster than the kaiapuni teacher population is and the impact can be immeasurable,” she writes, adding that she has had to turn away students because the school doesn’t have enough kumu and classroom space.

“We hope that the lessons we learn on working out the logistics of making this successful will only catapult us to the next level of delivering kaiapuni instruction in an innovative way yet maintaining the integrity of focusing on our vision and mission: perpetuating, revitalizing and normalizing the Hawaiian language and culture.”

In 2017, the DOE’s Office of Hawaiian Education created a Hawaiian Special Permit to encourage Hawaiian language educators to pursue teaching licensure to address the shortages of immersion school teachers and Hawaiian studies teachers. Educational specialist ‘Ānela Iwane says 19 people have the permit and are teaching in immersion schools.

In the future, Krug says he hopes there will be professional development courses for all DOE teachers who want to learn Hawaiian. In addition to getting more Hawaiian-language speakers to pursue teaching licenses, he says, “we have to get licensed people to become speakers.”

Across Sectors

In 2018, Hawaiian Airlines operated seven ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i flights, with boarding and in-flight announcements in Hawaiian followed by English translations.

John Borden, director of in-flight operations, remembers the first ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i flight – which flew from Honolulu to Hilo during the Merrie Monarch Festival – and says it was like a dream to hear the language spoken as if it were the days of the Hawaiian kingdom. “It seemed so normal, like it’s so new but so normal,” he says. “It feels right.”

Today, estimates say there are from 20,000 to 40,000 Hawaiian language speakers and Hawaiian language is used in some parts of business, media, government, science, tourism and other sectors. The use and proficiency of the Hawaiian language ranges, but what’s important, says state Sen. J. Kalani English, is that the language is being spoken.

“We’re just on the brink of Hawaiian being used again daily in everyday transactions, so it’s not uncommon to go out somewhere and hear people speaking Hawaiian – hearing young kids speak Hawaiian,” English says. “So all of those are the signs to me that the language is thriving.”

Hawaiian language can be heard on ‘Ōiwi TV, and multiple media outlets have Hawaiian word of the day segments and incorporate Hawaiian words. Amy Kalili, who writes and produces for ‘Ōiwi, anchored the first daily Hawaiian language news segment on a commercial TV newscast. Kalili, who has since worked in a variety of positions to advance the Hawaiian language, remembers the feedback KGMB received when ‘Āha‘i ‘Ōlelo Ola aired on its morning news show. People thanked the station for its efforts and said it was about time that Hawaiian was heard on TV, she says.

Hawaiian language can also be seen in astronomy. In 2018, two asteroids were given Hawaiian names through A Hua He Inoa, a collaborative effort led by the ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center, where a group of immersion and college students worked with Hawaiian language experts, education leaders and astronomers to name the discoveries. The two names were submitted to the International Astronomical Union and are pending adoption. Ka‘iu Kimura, the center’s executive director, says the program is an opportunity to raise the awareness and level of Hawaiian language locally and globally.

Pōwehi, the newly discovered black hole in space, was named by Larry Kimura. The Hawaiian word means embellished dark source of unending creation. | Photo: Courtesy of Event Horizon Telescope collaboration et al

“Just think about it if we’re successful in getting this embedded into astronomy, what would happen over the next 100, 200 years when new discoveries are being made that people around the world start using Hawaiian terms, just like we did with Greek and Roman terms,” says John De Fries, a local businessman who was involved in early discussions regarding the creation of A Hua He Inoa.

Some of that increased awareness has already happened at home. As a result of the A Hua He Inoa pilot with students, UH began offering Hawaiian language classes for the astronomy community. Kimura says about 115 staff and researchers signed up for the spring 2019 classes.

Several of Hawai‘i’s hotels already incorporate the language into their guest experiences. One example is Aulani, a Disney Resort and Spa in Ko Olina. The resort has employees – Disney calls them “cast members” – with varying degrees of proficiency in Hawaiian working in a variety of areas, from bartenders to valets to front desk workers. In addition, the resort’s ‘Ōlelo Room is a lounge where guests are at times surrounded by the language through interactions with fluent Hawaiian speakers, Hawaiian music and wood carvings of common objects that feature their corresponding Hawaiian words. Kahulu De Santos, Aulani’s cultural advisor, says she hopes other businesses will see the importance of learning and using Hawaiian to inform experiences for guests and the broader community.

Kalani Ka‘anā‘anā, director of Hawaiian cultural affairs for the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, says the authority is looking at ways to support renormalization efforts in the tourism industry and broader community. A recent effort, he says, was the launch of a Hawaiian language page on gohawaii.com, its website for prospective visitors, where they can learn common words and phrases. In addition, the authority’s board of directors meeting agendas are published in Hawaiian and English.

English says he applauds the businesses that have started to integrate Hawaiian. One example he cites is Bank of Hawaii, which has 385 ATMs with Hawaiian language capability and accepts checks written in Hawaiian.

“It’s just a matter of let’s just get people to use it. Whatever it takes,” English says. “Somebody … that wants to say ‘I want to start using Hawaiian,’ start. That’s what I’m telling everybody is just use it. Don’t be afraid of ‘I may use the wrong word. I may not get it correct.’ The main thing is to just use it and start using it and, you know, there’s many different ways to say it, so find your way and say it.”

But to encourage more use of Hawaiian, there’s also a need to provide more ways to learn it. One effort is the free Hawaiian language course on the language learning platform Duolingo. Kawai‘ae‘a, who is also co-chair of Kanaeokana’s Hawaiian Language Renormalization Committee, says the idea was to provide another way to help support families of kaiapuni students who don’t have time to attend face-to-face language classes. On March 21, the Hawaiian language course on Duolingo had 318,000 users.

Another effort brings Hawaiian language instruction into the workplace. Ku‘uleilani Reyes is the project manager of Papahana Kuaola’s Project Ho‘opoeko, which supports the growth of Hawaiian language immersion workplaces in the Ko‘olaupoko area. The three-year project is funded by a grant from the Administration for Native Americans and the idea, she says, is to help employees of Native Hawaiian-focused organizations become fluent in the language. Classes are taught at the workplaces using the Ka ‘Ālelo Matua teaching methodology, which is based off the Silent Way Method and New Zealand’s Te Ataarangi language teaching method. Ka ‘Ālelo Matua uses a Hawaiian-only approach with wooden blocks that represent different parts of speech and hand gestures to teach the language. She hopes that the organizations will eventually conduct their work in Hawaiian – and these impacts can spread to their families and, eventually, their communities.

Language revitalization typically starts with education, Borden says, which breaks down one barrier to bringing back a language. “I think the next barrier we’re starting to face is to normalize it in appropriate business industry,” he says. Many people believe there are limited career options for Hawaiian speakers, he adds.

Hawaiian Airlines is looking at hosting a career fair for Hawaiian immersion students, says Debbie Nakanelua-Richards, director of community relations. The idea is that the airline would serve as a catalyst for other organizations to send their Hawaiian speakers to connect with and show students there are now several careers that Hawaiian speakers can pursue.

Government Use

“When government starts using (‘ōlelo Hawai‘i) again, that’s the final legitimization factor,” says state Sen. English. “That’s the thing that says, OK, this language is thriving.”

English has been in the state Senate for almost 19 years and says he’s tried to get government to use Hawaiian in daily transactions by introducing bills to require the use of the language in things like letterheads, stationery and signage. Only one bill made it out of the Legislature before being vetoed, he says. Now as majority leader, his office publishes the Senate’s orders of the day in Hawaiian first and then English, and multiple Senate committees do the same with their hearing notices. He also says senators are accommodating requests to testify in Hawaiian. Interpreters can be requested, and he estimates that he and 10 or 15 other people in the Senate speak Hawaiian and can help relay testimony, if needed, for committee hearings.

“Previously, I was trying to get all of government to do it. Now what I’ve come to realize is we have to do it in pockets,” he says. He still pushes for the whole government to use Hawaiian, but today, he sees it used in different ways in multiple state agencies, like the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority and the state judiciary.

In 2015, the judiciary convened a task force at the request of the Legislature to examine the scope and cost of implementing Hawaiian language resources on the agency’s website. The group concluded that translating 21 priority pages of the judiciary’s website, plus the site’s navigation features, would cost $18,551. The task force also developed a budget – of $480,200 to be renewed annually for three years – to establish long-term resources and capacity building to train experts to meet the present and ongoing translation needs of the judiciary and other state agencies. (View the final report)

Although no state funding was appropriated to pursue those efforts, Rodney Maile, administrative director of the courts, says the judiciary continues as best it can to incorporate more Hawaiian, such as by offering Hawaiian language training to about 800 employees and doing bailiff calls in Hawaiian at the Supreme Court and the Intermediate Court of Appeals.

The judiciary is also working on increasing the number of Hawaiian language court interpreters and creating a Hawaiian language interpreter certification, says Daylin-Rose Heather, special assistant to the administrative director. In April, the judiciary’s registry of court interpreters included six Hawaiian language interpreters, including one for the Ni‘ihau dialect.

In 2018, public outcry resulted after a Maui district judge issued a bench warrant for a defendant who chose to only speak Hawaiian in his courtroom. Maile says that led to the state judiciary revising its court interpreters policy so that Hawaiian language interpreters will be provided or permitted during courtroom proceedings. Previously, it was up to the judge’s discretion as to whether a Hawaiian language interpreter would be allowed, he says, adding that people can also provide their own interpretations, meaning that a person testifying in Hawaiian can repeat his testimony in English, if he wishes.

Whatever they have in English should be in Hawaiian, especially the government. You know where the government was once, all business was handled in Hawaiian language. Why are we not handling it in the same way? Same thing with our courts, same thing with our education.” – Ekela Kaniaupio-Crozier, Hawaiian culture-based education learning designer and facilitator, Kamehameha Schools Maui

“The more we can encourage the Hawaiian language community and those who are interested in becoming court interpreters (to) attend the workshops when available and inquire about becoming a court interpreter, I think the better the policy will be implemented and really support the use of the Hawaiian language in the courts,” Heather says.

Puakea Nogelmeier is executive director of Awaiaulu, an organization dedicated to developing Hawaiian language translators and resources. He says all it takes on the part of the state to publicly renormalize Hawaiian language is the will. Right now, he says, Hawaiian is more decorative than functional.

“If they decided that Hawaiian was a functional part of the state, every custodian, secretary and CEO when they’re hired, preference would be given to one that had some fluency in Hawaiian language or history,” he says. “End of discussion. So you’d end up with offices that had capacity within themselves.”

He says part of the challenges with offering more government services in Hawaiian is that it’s unknown who in government has Hawaiian language skills – and there’s nothing in place to generate an economic drive for Hawaiian language speakers to learn the skills that make them economically viable. He says there are two solutions: One is to build capacity within the existing staff, and the other is to help the language community develop the skills that will help them get hired in state offices.

Kawai‘ae‘a of UH Hilo and Kanaeokana says she’s working with Hawai‘i County offices to identify Hawaiian speaking employees so people who visit their offices know who can speak Hawaiian. In Hawai‘i County, Hawaiian is the most common non-English language spoken among people aged 5 and older. Part of what the effort addresses is people’s attitudes about feeling comfortable with having Hawaiian around them as well as English, she says.

Hawaii Business Magazine previously explored what it would cost to provide more state government services in Hawaiian but found that no one was able to estimate the cost of doing so. (Read our previous coverage here.)

Looking Ahead

It takes one generation to lose a language and three to revitalize it, Kawai‘ae‘a says – and Hawaiian language is in the middle of those three generations. She says she’s seeing good progress, but there’s still a way to go.

Kaniaupio-Crozier of Kamehameha Schools Maui says Hawaiian language is not given parity with English, despite being an official state language: “Whatever they have in English should be in Hawaiian, especially the government. You know where the government was once, all business was handled in Hawaiian language. Why are we not handling it in the same way? Same thing with our courts, same thing with our education.”

Some people, she says, don’t see a need or value in having Hawaiian language in government and business when English is the dominant language. And it’s hard to say what comes first: government and business conducted in Hawaiian or enough speakers to justify the offering of those services.

“I think everyone just has to take their interest in just doing it. … All of us have to do something. That’s why we got as far as we did because all of us who have been doing it, we just did it. We didn’t wait,” she says. “And I think that’s the basis of the problem is waiting for us to build up a group. We’re doing our part as much as we can, but we need to have that public support.”

Nogelemeier adds: “The fact that the language survived here is a grassroots effort. Not to say the state hasn’t funded things and funded schools and everything, but never without huge pressure from the language community.”

Kawai‘ae‘a says an example is the Hale Kuamo‘o Hawaiian Language Center, which was established in 1989 by the Legislature to support and encourage the expansion of education in Hawaiian. It currently doesn’t have a standing budget or permanent staff members, so it has to rely on grants for its projects.

“But more important than funds is collective will. … If the state is reliant completely on tourism, tourism is reliant on uniqueness and the one thing that makes Hawai‘i unique is being Hawaiian. … It doesn’t seem to get traction,” Nogelmeier says.

Kalili is now director of Mokuola Honua: Global Center for Indigenous Language Excellence, which aims to support indigenous language revitalization globally. She says 2019 was declared the International Year of the Indigenous Languages by the United Nations and the Year of Indigenous Language by Gov. David Ige, which makes this year an opportunity to reflect on the progress Hawaiian language has made and strategically think about the next priorities.

Kalili says in countries where indigenous language programs are heavily supported by government, having a language plan is common. Revitalizing a language, she says, is not just going to happen through education, so these plans also reference how government, media, industry, economy, social services and other sectors can increase the use, acquisition and promotion of language. Senate Concurrent Resolution 180 urged ‘Aha Pūnana Leo to form a coalition to develop a Hawaiian language plan to accelerate the normalization of ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i. The resolution did not pass this year.

“We need to have a strategic response, a well thought out response, as to how and where Hawaiian could and should be used. I think again on a 30,000-foot macro level we’d like to see it be used and promoted in various spaces and places,” Kalili says.

“And I don’t think the onus is obviously all on government. You also want to see public, private and community efforts taking place. And even as individuals.”

Quicklinks

Part 1: State of the Arts

Part 2: “We’ve Really Moved the Needle”

Part 3: How You Can Help