2020 CEO of the Year Micah Kāne

Kāne ensures the foundation focuses on both the long-term quality of life statewide and the immediate needs of people who might otherwise be forgotten.

The Hawai‘i Community Foundation has been an important charitable force in the Islands for 104 years, but never more than in this year of the pandemic. Kāne ensures the foundation focuses on both the long-term quality of life statewide and the immediate needs of people who might otherwise be forgotten.

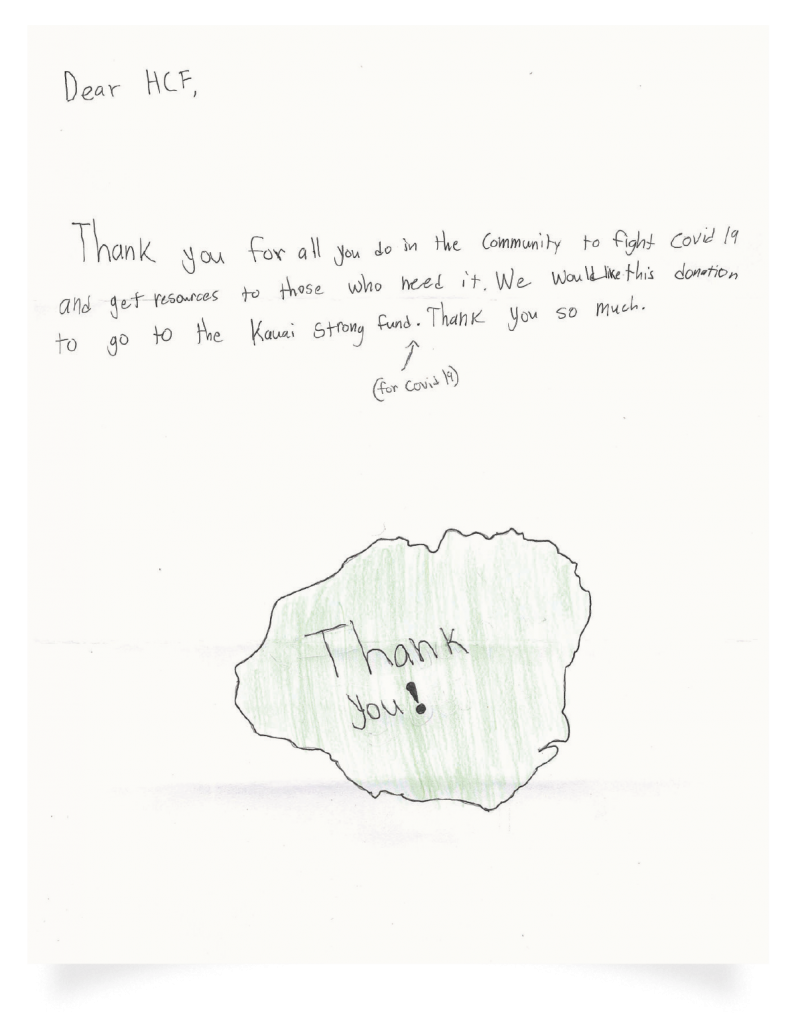

The plain white envelope had a Kaua‘i postmark but nothing else to distinguish it from other mail. Inside was a $20 bill, a sweet drawing and a touching note in a child’s careful printing.

“Dear HCF:

“Thank you for all you do in the community to fight COVID-19 and get resources to those who need it. We would like this donation to go to the Kauai Strong Fund.

“Thank you so much.”

That anonymous donation with its simple words melted the hearts of Hawai‘i Community Foundation staff who’ve been opening thousands of donation letters that have poured in to help mitigate the brutal consequences of the pandemic.

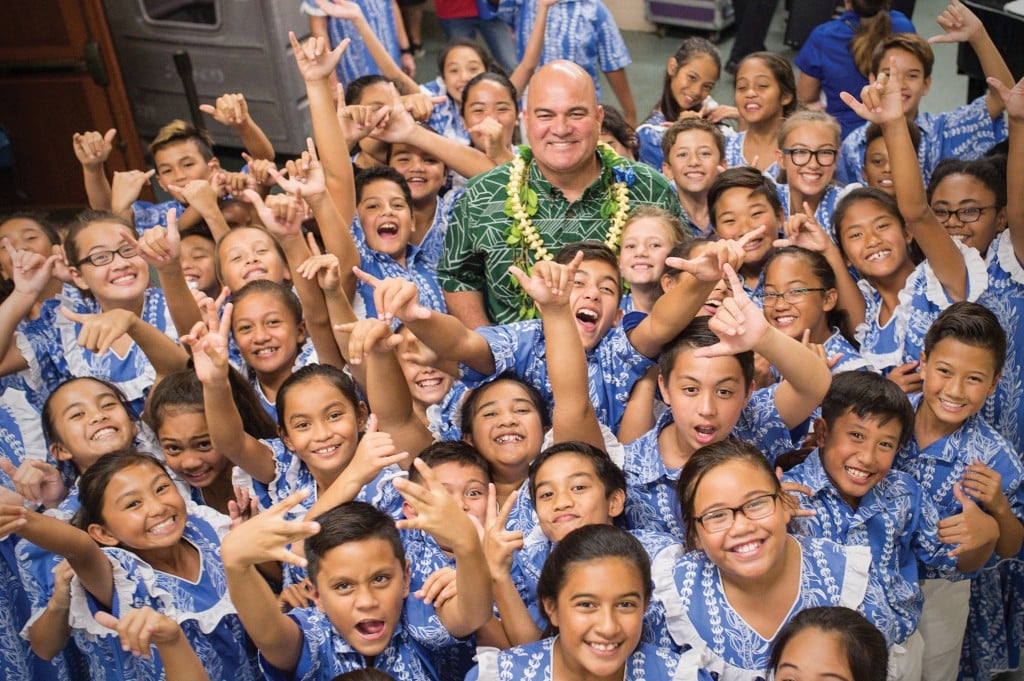

When Hawai‘i needed HCF the most, the foundation stepped into the breach created by the pandemic, led by its CEO, Micah Kāne. Between the pandemic’s start in March and early November, 125,000 households – almost half a million people – had received help from the foundation’s many programs and community partners.

“Because of our relationship with the nonprofits, we could move funds into their accounts quickly and deliver services very quickly,” Kāne says. The foundation has helped coordinate immediate communitywide assistance with rent, utilities, food, shelter, car payments and many other financial needs.

HCF has been a philanthropic leader in Hawai‘i for decades and never more so than under Kāne, who became CEO in January 2017 after seven years on HCF’s board. For those reasons and many more detailed in this story, Hawaii Business Magazine has selected Kāne as its CEO of the Year for 2020, the year of the pandemic.

Dual Focuses

Sometimes, Kāne and HCF’s work has been long-term and ongoing, such as establishing programs to meet important community needs; convening the community and targeting social investments around key issues like education, the working poor, civic engagement, the environment and many others; helping philanthropists target their donations for the greatest impact; and providing cost-effective services and administrative support for other charities and foundations.

Sometimes, Kāne and HCF’s work has been immediate: Within a few weeks of its March launch, the foundation’s Resilience Fund swelled to $12.3 million. Since then, another $9.1 million has been raised, all of it going to charities and government agencies that help people whose incomes and lives have been devastated.

The donations ranged from contributions smaller than that anonymous child’s $20 gift, all the way up to $3 million from the Bank of Hawaii Foundation – the largest corporate donation in HCF history.

State and county governments have also recruited HCF to distribute $57.6 million from the federal government’s CARES Act.

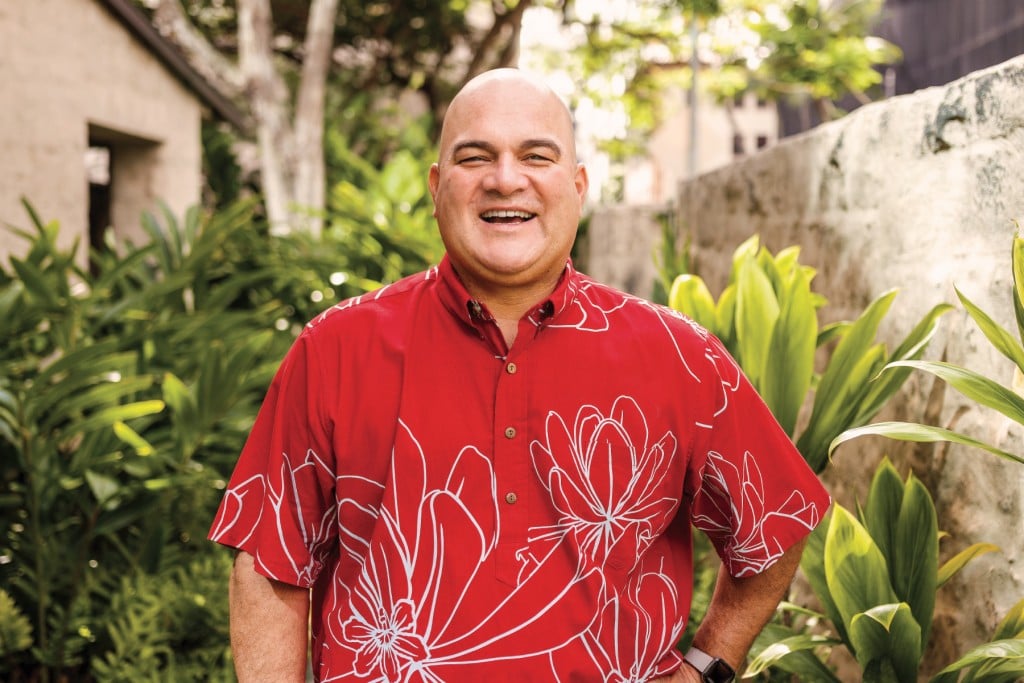

HCF has been an important philanthropic organization for over a century, but its new muscle and reach draw much from Kāne’s dynamic leadership and his sense of urgency in addressing systemic needs, including poverty, homelessness and the hopelessness found in many local communities even before COVID-19.

HCF’s traditional focus had been soliciting and managing legacy gifts that provided long-term charitable funding. But Kāne recognized during 2018’s devastating floods on Kaua‘i and Kīlauea’s eruptions that HCF also needed to react quickly and nimbly to crises. The pandemic validated that pivot.

“The nonprofit sector is oftentimes the first line of defense in disasters because they know the community so well,” says Darcie Yukimura, HCF’s VP of philanthropy. “Philanthropy provides flexible dollars that are able to respond quickly.”

Support Just in Time

Lei Agcaoili, a single mother with a 6-year-old daughter, says HCF funding kept a roof over their heads after she was laid off from her job as a bartender at a Kaua‘i sports bar.

“I remember crying and breaking down day after day,” she says. There was just $1,000 in her bank account – less than half of what she needed to get through the next month.

“I was scared … I’ve been in survival mode since my daughter was born,” Agcaoili says. “On one day alone I called the unemployment office 140 times from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and couldn’t get through.”

An eviction notice came before any government benefits kicked in, says Agcaoili. What saved her was a $4,800 zero-interest loan from the Kaua‘i County Loan Program, which is supported by HCF’s Kauai Strong Fund. She vividly remembers the call from the loan office.

“When Shanelle called me and said, ‘Hey girl, you got approved,’ I broke down crying. That covered me until everything else started to come through,” Agcaoili says. She could pay rent, buy food, pay utilities, buy gas for her car and cover her daughter’s school expenses.

Her case helps prove to Kāne the importance of the foundation’s dual focus.

“Foundations around the country have evolved to be more responsive to their communities, and to morph as the needs of the community demand,” he says. “When the Kaua‘i floods hit, it was one of the first times we stood up a fund to respond quickly to the needs of the community, and complement government’s response. With the Kaua‘i floods we were able to get resources out within 48 hours.”

Then the volcano blew. Again, HCF responded, and again Kāne recognized that this was the new normal, the new way the foundation had to work.

“In that window before the pandemic hit, we were able to develop a preemptive move to try to prepare for an emergency,” he explains. HCF created the Resilience Fund and realized the response to this new crisis had to be long term, he says.

“As a result of the trust established between donors and nonprofits, we were able to raise a significant amount of money.” For each dollar raised, Kāne estimated that community partners were able to step up with service and funding worth three times as much. Most of their work has been in partnerships with organizations such as the Castle Foundation, Kamehameha Schools, the Weinberg Foundation or individuals.

“So it has become more of a project by project strategy which I think has inspired more people to step up.”

Many Have Donated

Donations came from all over the country. “We have individuals who have made multiple contributions, like the small law firm that sends a new contribution each time they get a new client,” says Kāne. “They just keep coming back. One lady has given five separate contributions over the last five or six months. I see it because I recognize her name when I’m signing the thank you notes. It’s unbelievable she is trusting us time and time again to put her money to work.”

To HCF board member Toby Taniguchi, VP for store operations at KTA Super Stores on Hawai‘i Island, what has been so impressive is Kāne’s low-key, calm and grounded leadership and the way he sees the needs statewide.

“He recognizes there are inequities across communities and has been very intentional about understanding those needs in order to better serve those communities, Hawai‘i Island being one of them,” Taniguchi says. “Japanese call it on and giri, this feeling of responsibility – and also gratitude – to those who came before you, and those behind you.”

Though Taniguchi has been on the board barely a year, he was immediately impressed when he first met Kāne over coffee in Waimea. “I love the guy. … He’s a great guy. The moment I met him I felt I had known him forever.”

The HCF staff, 68 people in total, have also responded to Kāne’s leadership.

“It’s almost like living in his house,” explains Wally Chin, senior VP and CFO at HCF. “He treats you like family. He has a high value on trust and teamwork, so in building the leadership team, that was the first thing – to make sure we all trusted each other.

“Getting us on the same page was his first task, but with a caring nature. Before you meet him, he always asks how you’re doing. He’s more concerned about your well-being before the work.”

When HCF VP and chief of staff Jamee Kunichika faced a health crisis this year and sought treatment on the Mainland, Kāne acted immediately. “He literally dropped everything he was doing and started connecting me to people who can help guide me through this area I don’t know anything about,” Kunichika says. “That’s been super priceless. Every day he reached out to tell me he’s sending me good vibes. He has my back.”

She appreciates Kāne’s “collaborative leadership style.”

“He empowers and supports our team to make decisions together. It’s not always an easy process and he encourages us to embrace tension as we tease out answers. The local Hawai‘i style is you back off tension. He tells us to embrace the tension. We’re all going to have different perspectives and so teasing out different perspectives means our decisions can be the best they can,” Kunichika says.

Kāne says that the CEO of the Year honor should actually be given to the entire HCF team. “There’s nothing more important to me about this recognition than my team truly understanding that they own this – 110% of it. Especially during this time of COVID – we’ve spent way too much time together, highs and lows. We’ve grown as a team as a result of it. It’s been the silver lining and something I’m so proud of.

“One of the traits our team has developed is that we have become comfortable being uncomfortable. We recognize that that’s where the opportunity is – and also the risk.”

Help in His Childhood

To understand Kāne’s commitment to philanthropy is to understand his childhood. His mother died when he was 5, and he was accepted into Kamehameha Schools’ Indigent Orphan Program, which covered education costs from elementary school through university.

“I had a good father and a loving family, but my leg up was education. If not for that program at Kamehameha I don’t know where I’d be today. Kamehameha carried me through college, through graduate school.

“When I look out in the community, I see all that potential, and kids that aren’t given that same opportunity that I was given. I’m no better than many other kids coming out of the rural communities. It’s a gift I will never be able to pay back no matter what I do. That’s what drives me.”

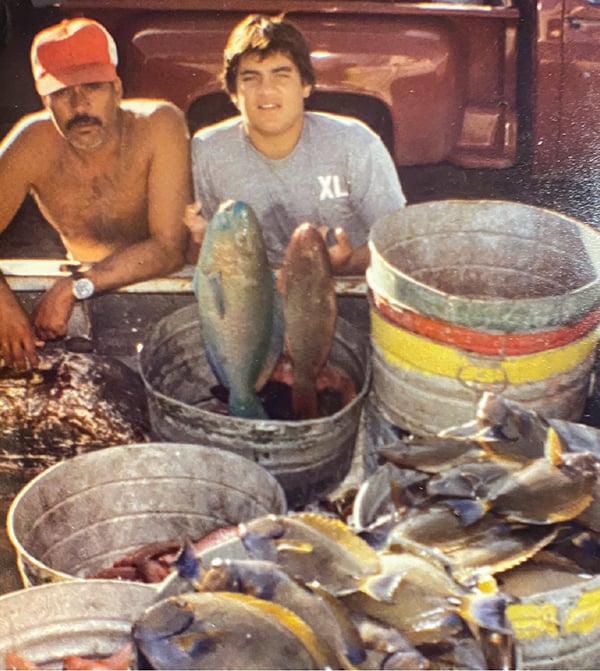

Other early influences included time at his grandmother’s home in Nānākuli, where the family fishing business kept him busy. His father, Atomic Kāne (“Bomb” is his dad’s nickname) and six uncles would be up before the sun, preparing their 24-foot wooden boat full of spearfishing gear for launch from Wai‘anae Boat Harbor. On weekends and when school was out, Micah and his cousin, Kapena, joined them.

Micah Kāne grew up helping in his extended family’s fishing boat. Pictured: Kāne, next to his father, Atomic Kāne, displaying the day’s catch.

Left to right: Kāne’s uncles Willie Souza, Boxer Pa‘aina and Tommy Souza sort their catch at Wai‘anae Boat Harbor next to the family’s boat.

With air tanks on their backs, the men would hunt reef fish like kumu, menpachi, weke, uhu, palani and moana kali along the Leeward Coast while the children served as deckhands. Half the men fished to supplement their family’s income; the other half supported their families entirely on their daily catch, which was sold at Tamura’s Market.

“I grew up on our boat, a working boat. So much of my lens on crisis management comes from that time I spent on the boat. From about 7 or 8 years old I was on the boat with six or seven grown men. You want a course in HR, you get it there. When things weren’t going well the tension can get really high. When we have a crisis at work my head goes back to the boat and how we got through those challenges.

“It was common,” he remembers, “for the ocean conditions to get dangerous, but we would still go. I recall one time coming back from Mokulē‘ia trying to get around Ka‘ena Point – trying to get back to Wai‘anae – and literally one-third of the side of our boat fell into the water because of the crashing of the waves at the point.

“We made it back, but it was a long and scary ride. I learned early on, keeping your cool during times of crisis gives you your best chance to survive.”

By his teens Kāne joined the spearfishermen in the water and came back with some of the catch – earning a portion of the proceeds. He says it’s a hobby he still loves but rarely has time to pursue.

Lasting Impressions

Those days were a deeply personal education for Kāne in how to handle crises and different personalities – often under intense pressure. It left him with both skills and a deep compassion for the Native Hawaiian community. That legacy has served him well throughout his career: in the rough and tumble world of state politics as chair of the Hawai‘i Republican Party and leader of Linda Lingle’s failed first campaign for governor; then while guiding the Department of Hawaiian Homelands from 2003 to 2009 during Lingle’s administration; as an executive with Pacific Links International, a global network of golf courses; as a trustee at Kamehameha Schools since 2009; and now at the helm of the Hawai‘i Community Foundation during a global pandemic.

Etched indelibly in his memory are the words his grandmother would say each time the family car rounded the point near the Kahe Power Plant on the way to her home.

“The first house in that community was Keaulana’s and every weekend she would say the same thing: ‘You know those politicians, they think the road ends at Keaulana’s, but there are a whole bunch of people trying to survive out here.’

“I never forgot that.”

One way he has made sure people like that are not forgotten is by supporting the ALICE families: Asset Limited, Income Constrained and Employed. These people are Hawai‘i’s working class, who before the pandemic might have had two or three low-paying jobs yet lived paycheck to paycheck. HCF and the Aloha United Way found that before the pandemic, 42% of the state’s families were ALICE.

COVID added to their numbers, Kāne says.

“The 42% who were ALICE pre-COVID have become 58% today. As a result of that you’re seeing some of our strongest workforce, the engine of our economy, leaving to find a place where it costs less. What is left are the poor and the wealthy. We’ve got to get in front of that. That’s a dangerous place to be if we lose that in its entirety.”

To change this dynamic Kāne says he has also been working with the state Legislature. “Most of the issues we think need to be addressed require policy changes; when you’re addressing systemic changes there are sacred cows that need to be addressed. It creates this political element and public conversation that creates risk to the organization, so we want to be as transparent as possible, so our thinking makes sense.”

To Kāne, engaging in the legislative process is necessary to create systemic change. “This has been welcomed by elected leaders. And this takes trust that we’re willing to take ownership of those issues to get organizations more engaged in the legislative process.”

New Directions

Bank of Hawaii CEO Peter Ho has been an HCF board member off and on for more than a decade and been board chair for the past two years. He has watched Kāne bring a new and dynamic energy to the foundation.

“He has moved us forward in really exciting ways,” says Ho. “Micah is an amazing intellect in a lot of ways and an incredible leader of people. He brings an inclusiveness that is rare, as well as a decisiveness that is also rare.

“Spring-boarding out of Kelvin Taketa’s long-standing tenure (as HCF CEO), Micah stepped in and was careful not to destroy anything Kelvin had built. But at the same time he was intent on understanding how we move it in a better direction. And that gave way to the CHANGE framework,” Ho says.

HCF and Kāne took the lead on the CHANGE framework, which recognized the connections between key issues in determining quality of life for everyone in Hawai‘i. Those issues are:

C: Community & Economy

H: Health & Wellness

A: Arts & Culture

N: Natural Environment

G: Government & Civics

E: Education

Ho says the community has been incredibly fortunate “to have had HCF during this crisis with COVID, and Micah is the driving force. We all need to appreciate that there were problems in the community before COVID and it only accelerated them.”

While HCF is based in downtown Honolulu, its work is statewide, supportive and usually collaborative. Yukimura highlights three cooperative Neighbor Island efforts: the Kaua‘i Resilience Project, the Vibrant Hawai‘i Project on Hawai‘i Island and House Maui.

“On Kaua‘i that project is aimed at reducing suicide among youth. A group of over 30 organizations, including nonprofits, mental health organizations and elected officials, come together every month to talk about our strategy and how to reduce the number. There was a record year in 2017 when the group came together because we had the highest suicide rate in the state there. I believe there were 21. In a small community that just reverberates.”

The foundation provides support for collective community action that aims to reduce that number on Kaua‘i.

“On Hawai‘i Island a grassroot community group got together and called themselves Vibrant Hawai‘i and focused on the high poverty rates. They did a year of information gathering and landed on several strategies to look at housing, health, food systems and youth programs,” Yukimura says. They also formed a nonprofit that can accept donations.

“On Maui it’s a more recently put together initiative called House Maui. The county has a very low rate of homeownership and is at the greatest risk of local residents leaving the island or state because of the cost of housing. This again is a group of individuals within different ranks of government and sectors of the community trying to map out how we can create housing acceptable to Maui residents.”

CFO Wally Chin says Kāne is constantly thinking about disadvantaged people and how to help them. “For us, it’s trying to keep up with him,” says Chin. “He wants to bring equity to all walks of life in Hawai‘i, which is different than equality. Equality means everyone gets the same thing. Equity is really about access to services such as preschools. If you use preschools as an example, there are 10 in Hawai‘i Kai and only one in Wai‘anae, so the need is really out there. For someone to drive to Hawai‘i Kai, that is not equitable.”

Philanthropy VP Yukimura remembers the day in March at the start of the pandemic when the staff packed up the office so they could work primarily from home. She wondered what was going to happen to the state’s economy and the revenue the foundation needed to support its mission. Kāne reassured her.

“I asked him, ‘What if this goes bad?’ and he just smiled and said, ‘We’re still going to be here. We’re in it for the community.’ He almost doesn’t see challenges. He’s looking through it to the other side.”

Where the Money Goes

The Hawai‘i Community Foundation acts in many ways: HCF collects donations and spends money directly or channels the money to other nonprofits; it spends or channels money on behalf of governments; and it provides administrative and other support to local nonprofits. HCF provided these examples of its work during the pandemic.

- Partnership: The City & County of Honolulu contracted with HCF to allocate federal CARES Act funds:

- Up to $31 million to provide services for vulnerable populations. Nonprofits supported include YMCA for childcare for at-risk families, Domestic Violence Action Center, Guide Dogs of Hawai‘i to help visually impaired students, Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement for emergency financial assistance, and many others.

- $6.3 million for local agriculture support. More than a dozen organizations have received funding to support local food supply, including Aloha Harvest, Hawai‘i Farm Bureau Foundation and Lanikila Pacific.

- Partnership: The state’s Office of Community Services contracted with HCF to distribute $5 million for emergency food support. The money went to four food banks, covering all counties: Hawaii Foodbank, Kauai Independent Food Bank, Maui Food Bank and The Food Basket on Hawai‘i Island.

- Partnership: The state Department of Human Services contracted with HCF to provide up to $15 million to support the reopening and operation of regulated childcare programs statewide.

- Hawai‘i Resilience Fund: Launched in March, the fund had received $12.3 million in donations by Nov. 4; $12 million had been granted so far to the community. Grantees listed here: tinyurl.com/HCFgrantees.

- Donor Advised Funds: Total grant distributions during the pandemic: $3.2 million.

- County-specific Strong Funds: $1.6 million distributed; grantees listed at tinyurl.com/HCFstrong.

- Stronger Together Hawai‘i Scholarship Funds: Program created due to the COVID-19 crisis to support Hawai‘i high school graduates in college. Total: 370 scholarships worth $2.5 million.

- Private foundations in which HCF administers funds: COVID-19 relief grants totalling $877,000.

- Others: Discretionary funds, specific area funds and unrestricted funds total $1.7 million.

- Total HCF has deployed for COVID-19 relief: $21.6 million as of Nov. 4.

Source: Hawai‘i Community Foundation

Some of the Groups HCF Has Helped

- Food banks and their distribution partners;

- Community health centers and specialized health services organizations supporting disabled, kūpuna and people at high-risk of COVID-19;

- Financial aid organizations providing emergency grants;

- Youth-serving organizations including YMCA, YWCA, Boys & Girls Clubs, KEY and Kupu;

- Schools and after-school programs, including those supporting remote learning;

- Child and family support organizations including YMCA, Catholic Charities, Child & Family Service and Salvation Army;

- UH for emergency grants for students, COVID-19 support and economic data analysis.

Source: Hawai‘i Community Foundation

CELEBRATING THE 2020

CEO OF THE YEAR

Date: December 10, 2020 at 3PM

Tickets: $25.00*

*Proceeds from ticket sales will be donated to the Hawaii Foodbank![]()