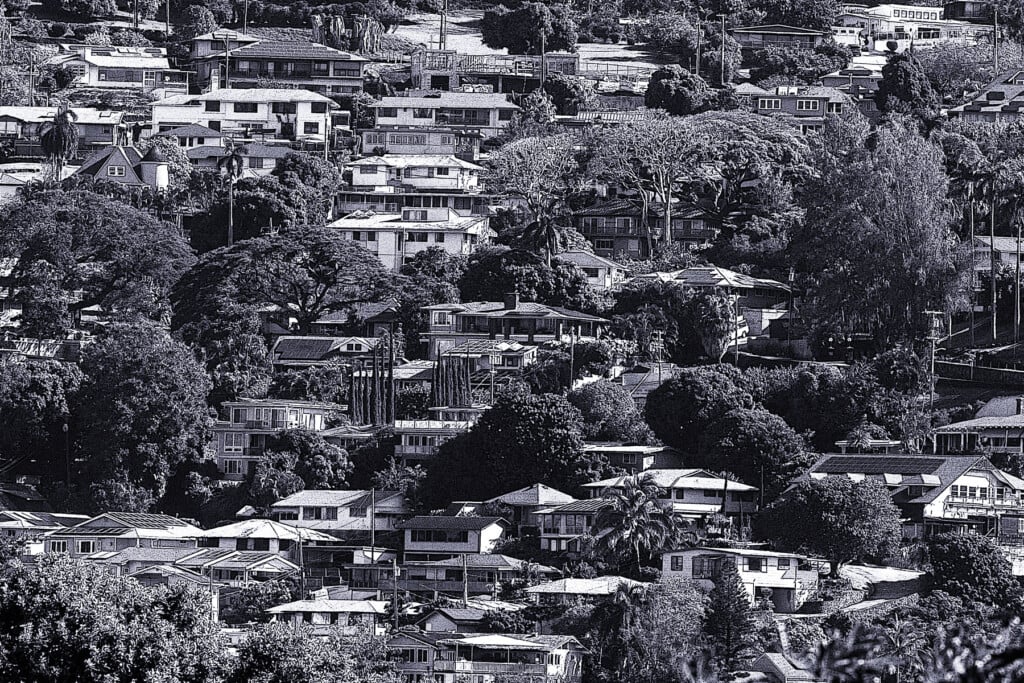

Soaring Hurricane Insurance Rates Leave Hundreds of Hawai‘i Condo Buildings Under-Insured

One local insurance agent estimates that the owners associations for as many as 390 buildings have renewed their policies with less than 100% replacement coverage.

Hawaiʻi hasn’t taken a direct hit from a major hurricane since Iniki devastated Kauaʻi and damaged homes along Oʻahu’s Leeward Coast 31 years ago. Nonetheless, mortgage lenders require Hawaiʻi homeowners to carry hurricane insurance that can cost two to three times the annual premiums for a conventional homeowner policy.

A condominium building or complex carries a master hurricane policy that covers 100% of the cost to replace the property – millions of dollars in many cases. Now premiums for those policies have risen so high that hundreds of owner associations are reducing coverage to less than 100%.

That’s creating headaches for everyone associated with Hawaiʻi condos, from lenders to insurance agents to buyers and sellers of condos.

“Right now, hurricane insurance is very expensive, and these condos can’t afford to pay for it,” says Sue Savio, president of Insurance Associates in Honolulu, whose clients include many of the condo associations on Oʻahu. “So there are a slew of condos, mainly high-rises, mainly Oʻahu, but other islands too, that don’t have 100% hurricane coverage.”

Savio estimates that owners and condo associations at 375 to 390 buildings, including new high-rise towers in Kakaʻako, have opted to renew their hurricane insurance policies with less than 100% replacement coverage. There are four standard insurance companies that write property and hurricane policies for condos, according to Hawaiʻi’s rules, and one, State Farm, continues to do renewals but hasn’t issued a new policy in the Islands since Iniki in 1992. The other three are First Insurance Co. of Hawaiʻi, Allianz and Dongbu Insurance.

Rates for hurricane insurance and regular homeowner policies in Hawaiʻi have been driven up by disasters around the U.S. and the world. The market for reinsurance, which is the insurance that property and casualty insurance companies pay to share their risk, is global, so storms and other catastrophes that strike anywhere in the world impact what homeowners and condo associations must pay for coverage in Hawaiʻi.

Some condo associations are forced to go to the secondary market if they are dropped by the standard insurers for having too many claims, or if their buildings have put off renovations or deferred maintenance on big-ticket items such as aging pipes. Savio notes that more than 700 condo buildings on Oʻahu were built before 1990, so there are a lot of old pipes.

Insurers on the secondary market are not bound by state rules or rates, so their prices can be more expensive than from standard carriers.

Savio cites the example of one high-rise in Waikīkī: The condo association had been paying an annual premium of $235,000 for property and hurricane insurance and had already been dropped by two of the standard insurance companies when the third declined to renew. The reason: The building’s aging plumbing hadn’t been replaced.

“They had to go to the secondary market and it was $1.2 million,” she says. “That’s $1 million of maintenance fees down the tubes because they didn’t fix their pipes.”

Harder to Get Condo Mortgages

The consequences of under-insured condo buildings filter down to the individual owners. People who want to buy units in buildings with less than 100% replacement coverage may have difficulty finding lenders willing to give them mortgages – in such cases, most local banks won’t lend them money – or they may have to pay higher rates.

That’s because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which purchase mortgages from banks and other lenders, require that multifamily properties have windstorm coverage (which includes hurricanes) for “100% of insurable value.”

Hawaiʻi state law, specifically Hawaiʻi Revised Statutes Chapter 514B governing condominiums, has a similar rule. It requires property insurance “in a total amount of not less than the full insurable replacement cost of the insured property” but prefaces that with “unless otherwise provided in the declaration or bylaws.”

Banks and other lenders in Hawaiʻi started noticing that a few condos had less than 100% coverage about a year ago, says Linda Nakamura, a legislative chair for the Hawaiʻi Mortgage Bankers Association. And over the summer, when lenders began seeing more and more under-insured condos, Nakamura and Victor Brock, also a legislative chair at the HMBA, began sounding the alarm with their members and state officials.

They have also met with state Insurance Commissioner Gordon Ito to talk about what could be done, such as looking at changes to HRS 514B, or attracting more insurers to do business in Hawaiʻi. They also looked at opening up the Hawaiʻi Hurricane Relief Fund, which has reserves of $189.7 million.

“It’s kind of snowballing right now,” says Brock. “It’s in the discovery phase for some lenders that the situation is going on.”

While local lenders have become aware of the situation, most mainland lenders are still writing mortgages for those condos, even those that have local offices in Hawaiʻi. Brock points out that while the mainland lenders may have local loan officers, the underwriting may be done on the mainland by people less attuned to hurricane insurance.

Unique to Hawai‘i?

Hawaiʻi may be the only state where widespread under-insurance of condos complexes is happening.

“We have asked around and could not find other states with this issue,” Nakamura says. “We’ve also reached out to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to ask them because they must know if different states are not selling to them because of this, but they could not tell us.”

She notes that Florida has had several major hurricanes in recent years, including Hurricane Ian, which caused more than $50 billion in damage in 2022, and Hurricane Idalia, which caused up to $5 billion in damage in August 2023.

Meanwhile some Hawai‘i lenders may require higher down payments or higher credit scores from condo owners, says Jay Miller, a loan officer at Hawaiʻi Mortgage Group.

“We have had some success running loans through our mainland partners, but I don’t know how long it’s going to continue,” he says.

Some buyers are also purchasing supplemental hurricane policies as gap coverage to make up for the shortage,” says Realtor Jonathan Ford, principal broker of Honolulu Property Finds, better known by its website, HiCondos.com.

“I don’t think it’s on people’s minds,” says Ford, who hasn’t yet had any clients turned down for loans because of hurricane insurance. “I think it’s going to be an unhappy surprise when it does happen.”

Condo owners in buildings with insufficient coverage may find it hard to sell their units or get home equity loans.

“They’re not going to be able to get a home equity loan if they need to fix anything, if they’ve got a major item in their unit that needs to be fixed,” Nakamura says.

Brock anticipates a major impact on first-time homebuyers, since condos comprise such a high percentage of Hawaiʻi’s housing stock, especially on Oʻahu.

“If you think about affordable housing in Hawaiʻi, in the majority of the state, the most affordable housing is a condo. It’s going to create complications for folks with low to moderate income,” he says.

“If they can’t get financing because the building doesn’t have sufficient hurricane coverage and no lender is willing to make a loan, or if their lending options are limited, it’s going to be a bad situation.”

It’s one more thing that’s going to make it harder to buy or sell a condo in Hawaiʻi, say the experts I spoke with.

The 2021 collapse of the Surfside condo building in Miami is also having a ripple effect on condo lending. This year Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac made permanent the rules for condo lending that were created in the wake of that disaster and ceased buying loans for buildings or projects that have put off major repairs – such as replacing old pipes. The new rules also prohibit the sale of a loan on a condo building that has unfunded repairs totaling more than $10,000 per unit.

Major litigation cases can also make a condo ineligible for lending under Fannie Mae rules, as well as if a building is considered a hotel-condo, or if it has too much commercial space. While condo associations are responsible for purchasing the master property and hurricane insurance policies for their buildings, individual condo owners are also required to buy what’s known as H06 policies. Such homeowner insurance policies cover everything inside the walls of a unit, from kitchen cabinets and appliances to furniture, clothing and other personal possessions, and typically cost a few hundred dollars per year.

But those are getting harder to get, too. Savio says one company is not renewing policies, while another will only insure condo units if the building’s pipes are 15 years or younger.

And that’s only if a customer hasn’t made too many claims.

“Nobody is writing policies now for anyone who has two claims – nobody,” says Savio.

Climate Change Creates Challenges

Recent storms like Hurricane Lane in 2018 have brought wind and flooding to parts of the state, but there has been nothing like the $2.3 billion in damage caused by Iniki in 1992.

But climate change is bringing more weather-related catastrophes. The National Centers for Environmental Information says that in 2023, as of Dec. 8, the U.S. had been affected by “25 confirmed weather/climate disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion each.” That record total of events – which includes inflation adjustments for previous years – exceeds the previous annual record of 22 events; the annual average over the past five years is 18, a higher average than in previous decades.

The Aug. 8 wildfires on Maui are considered weather-related because of Hurricane Dora, which was passing south of the Islands. Strong winds influenced by Dora drove the fast-moving fires that leveled Lahaina and killed at least 100 people.

“We’ve always been rated for hurricanes; we’ve never been rated for wildfires,” says Savio, who noted that Oʻahu had its own major wildfires this year in Mililani and Waiʻanae. “What’s happening now is West Oʻahu and some areas are going to be rated with wildfire exposure. Parts of all islands are going to be rated for wildfires.”

Brock noted that Acapulco, like Hawaiʻi, was unaccustomed to destructive hurricanes making landfall before Hurricane Otis slammed into the Mexican beach resort city on Oct. 25, killing 50 people. It’s estimated the storm caused up to $4.5 billion in damage.

“That was a tropical storm that went to Category 5 hurricane in less than 12 hours,” he says. “With climate change, I think that the insurance companies are saying we can’t base our losses on history because things are changing with climate change and look what happened in Acapulco.”

All of it adds up to turmoil in what Savio calls “condo land.”

“There’s a lot of unrest and turmoil, not only for the owners (but) for the management companies, for the boards, for the property managers, for the insurance agents and, of course, for the insurance companies,” she says. “There’s a lot of turmoil.”